History

The castle was erected shortly after the Norman invasion of England in 1066, when William the Conqueror set William Fitz Osbern as Earl of Hereford. William enlarged his lands by winning Monmouth and Chepstow, and began building castles there to subdue the Welsh. White Castle, originally called Llantilio, was one of the three wood-earth strongholds built at that time in the Monnow Valley (the others are Grosmont and Skenfrith). It was to protect the route from Wales to Hereford and guard border lands.

William Fitz Osbern was killed in the Battle of Cassel in Flanders in 1071, and his son Roger de Breteuil rebelled against the king in 1075 and lost his fortune. When a great Welsh uprising broke out in 1135, king Stephen in response reorganized the border march, bringing White Castle and its sister strongholds in Grosmont and Skenfrith under the control of the Crown, and creating a lordship known as the Three Castles. After a period of peace under the rule of Henry II in the 60s of the twelfth century, in 1182 again fighting broke with the Welshmen. The nearby castle at Abergavenny was almost completely destroyed, which made it necessary to strengthen the defense of White Castle. In the years 1184-1186, the royal official Ralph of Grosmont made works costing 128 pounds, erecting a stone defensive wall and a keep, but the attack did not finally take place.

In 1201 king John gave the Three Castles to Hubert de Burgh. Hubert was a small landowner who became John‘s chamberlain when he was still a prince, and became a powerful royal official when John inherited the throne. He began to modernize his new strongholds, starting with Grosmont, but was captured during fights in France. During his captivity the king handed over the White, Grosmont and Skenfrith castles to William de Braose, rival of Hubert. However, already in 1207, William fell out of royal favors, and his son, also called William, engaged in the so-called First Baron’s War with the king. After the release, Hubert regained power and influence, becoming Earl of Kent and regaining the Three Castles in 1219 during the reign of king Henry III. He ruled them until 1232, when was imprisoned because of the intrigues of his opponents, and White Castle was put under the command of the royal servant, Walerund Teutonicus. Hubert returned to White Castle in 1234-1239, but the sisterly strongholds were finally granted in 1254 to the eldest son of king Henry, prince Edward, and later, in 1267, to his younger brother Edmund.

In the 13th century, the castle was significantly rebuilt. It is most often assumed that this took place in the 50s and 60s, but it is also possible to have a slightly earlier dating, during the reign of Hubert, who would carry out the reconstruction in two stages: in the years 1229-1231 and 1234-1239. During this time, the fortifications were first described in the documents as “White Castle”, due to the bright color of its outer walls.

In 1262 the castle was prepared for defense in relation with the attack of the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd on Abergavenny, but the fights for White Castle did not happen. In 1267, Edmund, Earl of Lancaster and commander of the royal forces in Wales, received the Three Castles, which for several centuries belonged to the later Duchy of Lancaster. The conquest of Wales by king Edward I in 1282 caused the castle to lose its military significance. Minor repairs were carried out in the fifteenth century under the reign of king Henry VI, but in 1538 the White Castle ceased to be used, and then fell into disrepair. In the 17th century it was in such a bad condition, that it was not used during the English Civil War.

Architecture

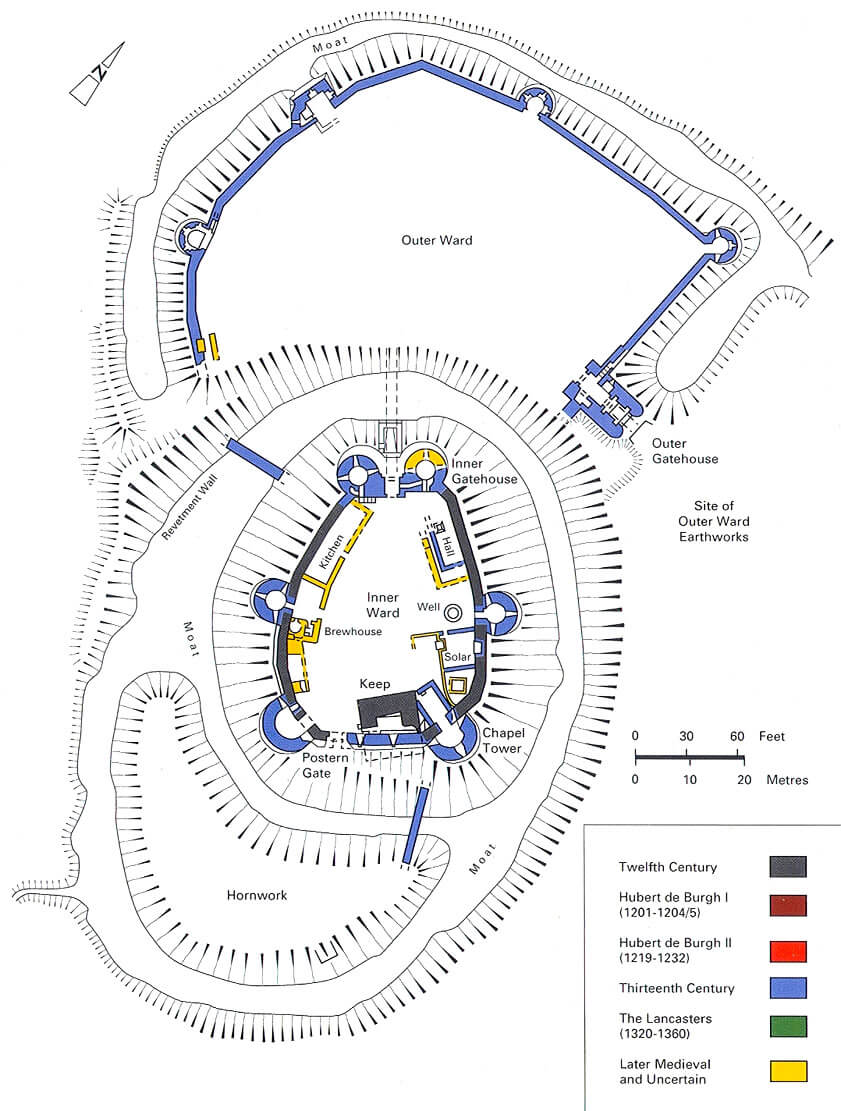

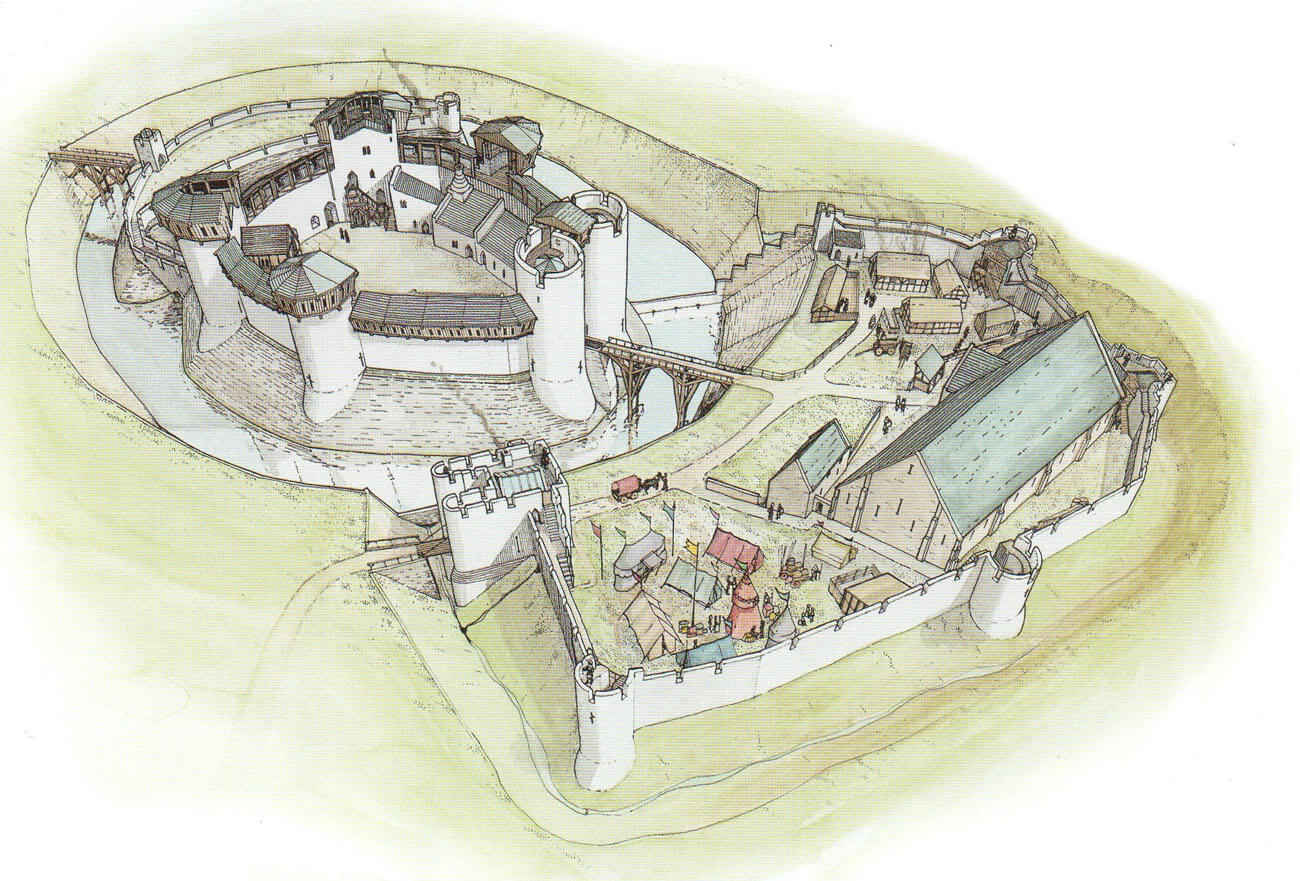

The castle was erected on a hill near the village of Llantilio Crossenny. Originally it was a timber and earth structure, rebuilt in the second half of the 12th century. Then it received a stone perimeter of defensive walls 1.7 meters thick with an oval shape and dimensions of about 46 by 34 meters. In its south-eastern part, a quadrilateral keep was built, measuring approximately 10 x 10 meters with walls up to 3 meters thick, probably adjoining by one side to the defensive wall. The original entrance to the castle was from the south.

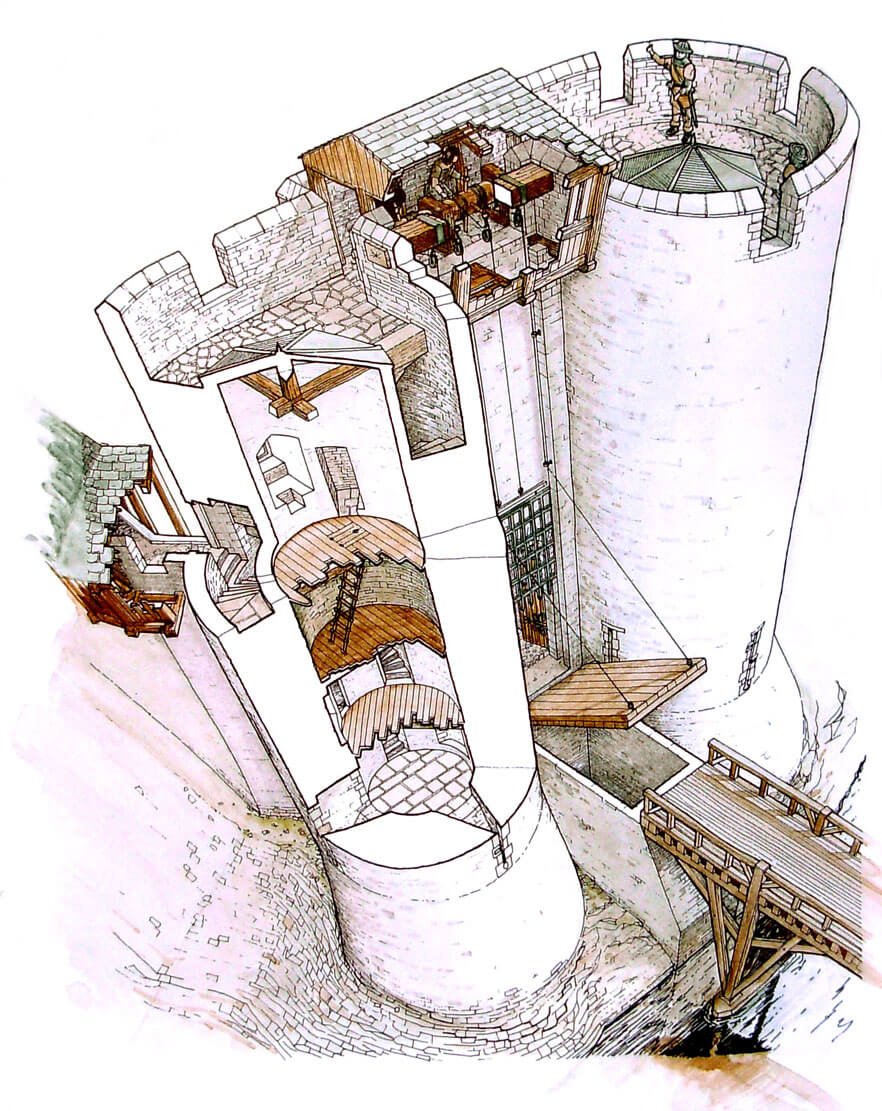

In the mid-thirteenth century, the castle was significantly expanded. The ring of defensive walls was reinforced with four, four-storey (basement, ground floor, two upper floors) semicircular towers, and the new gate located from the north was created from two, powerful, cylindrical towers flanking the passage between them. It was one of the earliest gate complexes of this type that were created on the British Isles.

The gate towers had a massive, battered plinth, ensuring the stability of the structure located next to the slope of the ditch. Inside, there were four floors separated by wooden ceilings, the lowest of which was equipped with loop holes protecting the entrance, and the upper floors were lit by windows pierced from the inner ward. A short passage, topped with an pointed barrel vault, was protected by a portcullis, two doors (blocked by drawbars placed in the wall openings) and a drawbridge, which blocked the passage when raised, and opened the stone pit. The portcullis was quite unusual, because it was added from the outside after finishing the gate, and because of that it was pulled up in the guides up to the height of the breastwork on the external facade. The north-east gate tower in the 15th century had to undergo significant repair work, probably as a result of a partial collapse. Both towers were accessible through portals in the ground floor from the side of the courtyard and portals at the height of the crown of the perimeter walls, with the eastern tower additionally connected to the gate passage. Spiral staircases in the thickness of the wall from the courtyard side ensured communication between the floors separated by wooden ceilings. For greater security, staircases were not created in one string, but exits were placed on individual floors in different places. In the eastern tower, the second floor was even omitted by the staircase, serving as a warehouse accessible by a ladder. The top floors were higher than the defensive walls and provided access to a small room above the passage, from where the portcullis was lowered and raised. Perhaps it was equipped with hoarding, although the gate opening mechanism itself, hidden only behind a wooden wall, had to be exposed to heavy missles and fire.

Four horseshoe towers of the upper ward, about 8 meters in diameter (east and west one) and about 9,7 meters (two south one), had three main floors. The entrance to the western tower led from the inner ward. The first floor was unlit and maybe only available down from the second floor, which was accessible from the level of the defensive wall. The second floor also had no openings on three sides, while the back part could have been open or closed with a timber wall. At the very top there was a combat floor, accessible from the defensive wall-walk by a dozen or so stairs. The opposite eastern tower had a similar form, but it was additionally equipped with a cylindrical basement with a depth of just over 3 meters, and the upper storey’s inner wall was made of stone, not wood. The two southern towers were slightly larger and differed with interiors of a horseshoe-shaped form (about 5.5 meters in diameter), in contrast to the cylindrical interiors of the northern towers. All the towers were crowned with battlement and probably wooden porches protruding from the face of the walls (hoardings).

The defensive wall and towers were equipped with atypical arrowslits in the shape of crosses, moved vertically so that one side was higher than the other. This setting helped to improve the defender’s field of view. At the inner ward, to the east of the gate, there was a hall building, next in the eastern part a building with a heated by fireplace chamber (solar), and a chapel connected with one of the towers. Chancel was located in the tower and was illuminated by three loop holes. Next to one of them in the wall there was a piscina for washing church vessels. An chancel arch was created from the portal leading to the tower, and the nave was a half-timbered building at the courtyard. The interior of the presbytery was plastered and covered with red paint forming quadrangles on a white background, quite a common motif found, among others, in Tintern Abbey and Chepstow Castle. The keep in this period probably did not function anymore (the last known information about its repair comes from 1256). The building with a private chamber was originally longer, but in the late Middle Ages in its outer side (from the courtyard side) another room with a fireplace was inserted. The small building in the corner contained a stone latrine pit, the size of which indicates that it was probably intended for the garrison.

Right next to remains of keep, there was a side, postern gate in the southern part of the perimeter. It led to a small bridge over the moat and further to the earth ramparts defending the castle from the south (hornwork). Initially, these ramparts were fortified with a wooden palisade, later replaced by a stone wall with a cylindrical tower in the west corner and a gatehouse in the east. The western side of the inner ward was occupied by the late medieval economic buildings: malt house, bakehouse and kitchen. The outer defense was deep, reinforced with a wall and a water-filled moat. It was controlled by two dams: in the south-east and north-west.

On the north and north-west sides of the castle there was an outer bailey, which stone walls were erected in the mid-thirteenth century. It had dimensions of about 98 by 52 meters and was reinforced with four towers, three of which were semi-circular, about 6 meters in diameter, two-story, and one four-sided 8.4 meters wide. The latter probably housed living quarters, because it had a fireplace and a latrine. All were crowned with battlements, strongly protruded in front of the face of the wall towards the ditch and connected to the wall-walk of defenders in the crown of the walls. Cylindrical towers in the ground floor had an unlit room, and the upper floor was based on a wooden ceiling and equipped with arrowslits. From the side of the courtyard, all the towers were closed with wooden or half-timbered walls.

The outer gate was placed in the eastern part of bailey, next to the moat of the upper ward. It consisted of two flanking towers, protruding from the four-sided gatehouse. It had a portcullis and a drawbridge over a probably waterless moat. The gate passage itself, 13 meters long, flanked by walls 2.5 meters thick, was closed at both ends by a doors. The ground floor also housed a guard’s chamber with a fireplace placed on one of the walls, separated from the gate’s passage by a wooden partition wall. On the opposite side, a few steps led to the latrine located in the wall protruding towards the moat.

Across the courtyard of the outer bailey, on its northwestern edge, next to a group of smaller wooden houses, a large building was erected, probably a barn, measuring 35 by 20 meters. In the niche formed in the western, extreme part of the wall, next to the moat, there was a latrine, another latrine was also in the west tower (instead the lack of latrines in the upper ward was striking).

Current state

The castle has been preserved in the form of a legible ruin with almost full circumference of the upper castle’s walls (inner ward) and most of the fortifications of the outer bailey. Unfortunately, none of the residential or economic buildings survived, only the foundations are visible. The castle is currently managed by the agency of the Welsh cultural heritage (Cadw). It is open to visitors free of charge for most of the year.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Knight J., The Three Castles: Grosmont Castle, Skenfrith Castle, White Castle, Cardiff 2009.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Remfry P., White Castle and the Dating of the Towers, “The Castle Studies Group Journal”, No 24, 2010-2011.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.