History

The stone parish church was built in Tenby in the first half of the 13th century, probably on the site of an older church from the 12th century, since Giraldus Cambrensis, a Welsh monk, chronicler, linguist and writer, is said to have been the parish priest of Tenby as early as 1172. At that time St. Mary’s was supposed to have been under the Benedictine monastery of St. Martin in Sées in Normandy, after which it was transferred around 1098 by Arnulf de Montgomery to the Benedictine priory at Monkton near Pembroke, a branch of the Sées Abbey.

The stone church, from the first half of the 13th century, was probably devastated in 1260, during the capture of Tenby by the Welsh forces of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd. Its reconstruction may have been aided by William de Valence, the first Earl of Pembroke, who held the local lands through his marriage in 1247 to Joan, daughter of Joan Marshal and Warine de Munchensy. William and his wife granted the town charter, founded the Hospital of St John the Baptist, completed the town fortifications and probably endowed the rectory of St Mary’s Church from the lands of the lordship.

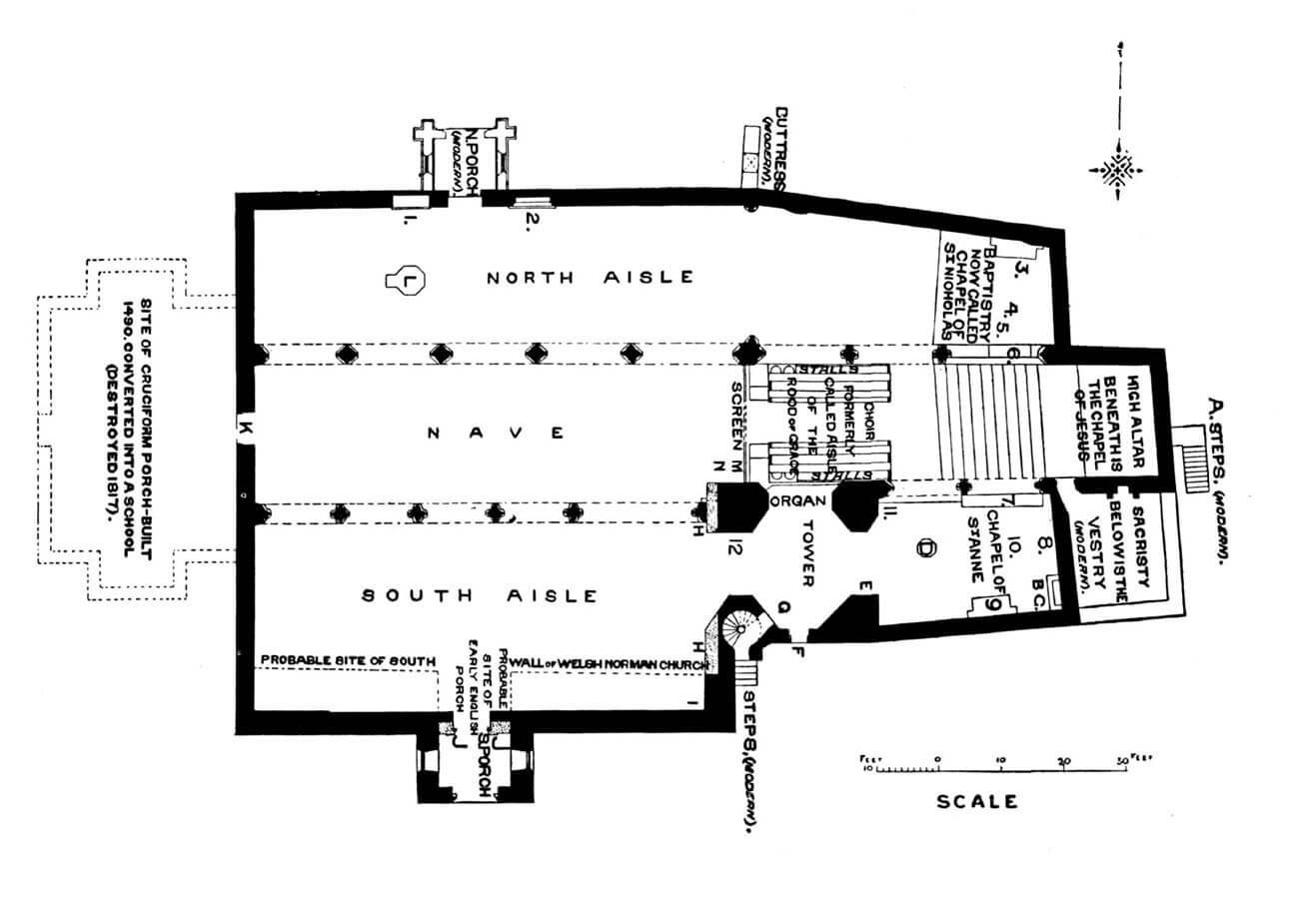

In 1291, the church at Tenby was recorded in the Taxatio Ecclesiastica, where its annual income was valued at a considerable sum of £16, 13, 4d, a tenth of which was to be given to the king Edward I Longshanks as part of the support of the Pope to the expedition to the Holy Land. The large income was due to the large population of the wealthy port town, which also reflected the considerable size of the church itself. Moreover, at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries it was expanded by a transept, a southern porch and the eastern part of the extended chancel. The tower may have already been built at that time, although it is possible that its construction began a little later, after the mid-14th century. Then, at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, the northern aisle and the southern chapel at the chancel were built.

In the first half of the 15th century, due to the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, King Henry V took away all the privileges of foreign monasteries that had been granted on the island. In 1440, the patronage over the church in Tenby was transferred to Humphrey Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester and Earl of Pembroke, who gifted it to St Albans Abbey the following year. However, in the second half of the 15th century the next Earl of Pembroke, Jasper Tudor, took a great interest in the development of Tenby and may have had a greater influence on the late Gothic expansion of the church than the monks. During this period, in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the chancel was extended once more, the north chapel and west porch were built, and the annexes on the south side of the nave were rebuilt. The connection between the church of St. Mary and St Albans Abbey ended in the 1540s when monastery estates became the property of the English Crown, in connection with the Reformation of Henry VIII.

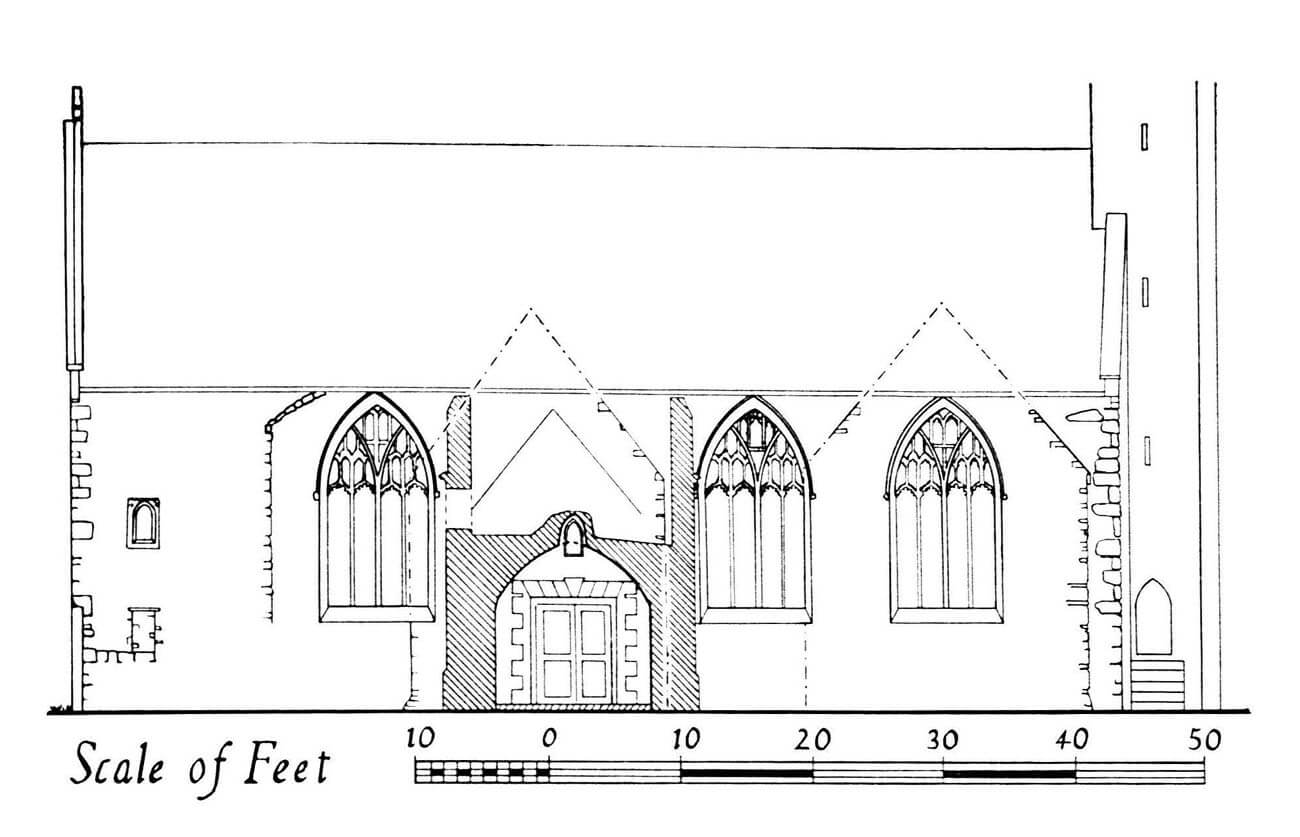

In the early modern period, the church probably avoided major architectural changes, limited to partial replacement of the window frames in the 17th century. The expenditure recorded in the 18th century would suggest that only minor repairs were carried out on the church at that time. In the early 19th century, the impressive west porch was converted into a school, but unfortunately, in 1831, the decision was taken to demolish it. In the 1840s and 1850s, the north aisle and both chapels by the chancel were partially rebuilt. In accordance with Victorian fashion, some of the windows were also replaced with neo-Gothic ones. Around 1850 a sacristy was built, and in the years 1862-1866 and in 1885, further repairs works were carried out, combined with the construction of the north porch. The modern renovation of the 1960s focused mainly on the valuable medieval roof truss and the uncovering of the medieval windows blocked in the early modern period.

Architecture

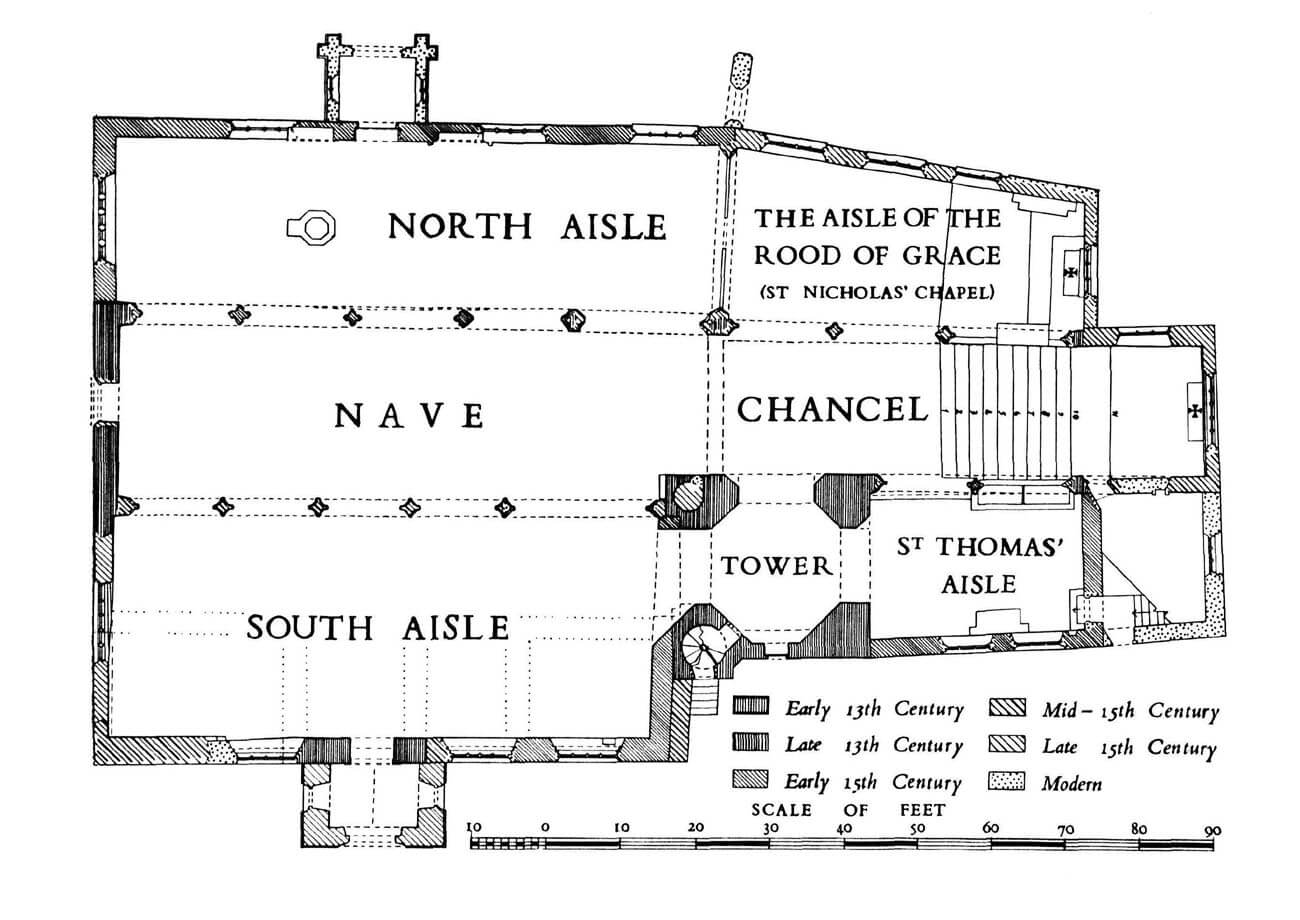

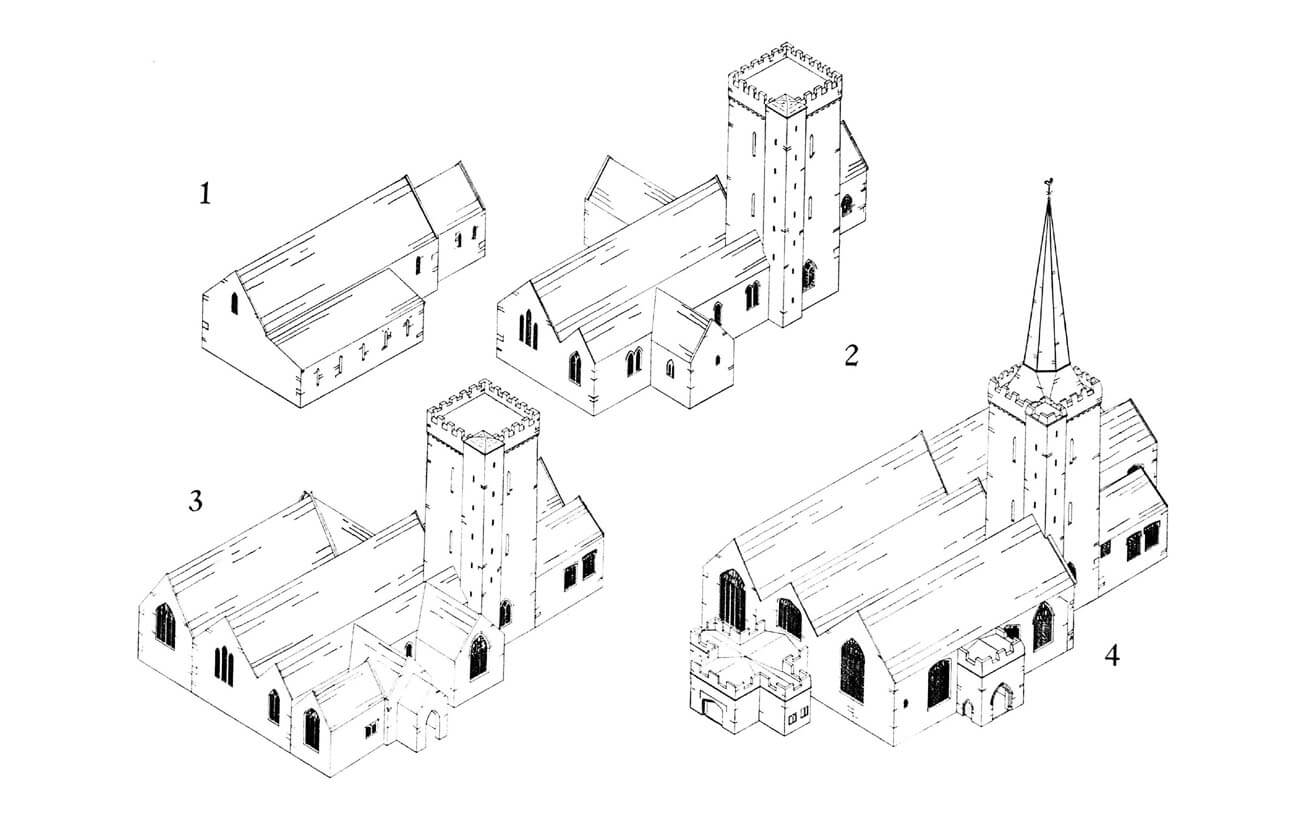

The church from the first half of the 13th century was distinguished by its considerable size, as for a Welsh religious building from such an early period. At that time, it consisted of a rectangular, strongly elongated nave, a chancel on the eastern side and a narrow southern aisle. The latter had a western facade in line with the nave, but was shorter, perhaps due to the planned transept from the beginning. The chancel was originally two-bay, closed on the east by a straight wall. Its width was slightly smaller than the nave, as was its height. Both main parts of the church must have been covered by separate gable roofs, while the southern aisle, due to its small width, probably by a mono-pitched roof. The church walls must have had late Romanesque windows, i.e. narrow, splayed towards the interior, closed with semicircular or slightly pointed arches. The entrance portals could have been placed in the longitudinal walls.

At the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, a transept was added to the nave, probably built on the wave of the emerging popularity of this element of sacral architecture in Wales, which reached its apogee in the later years of the 14th century. In addition, a southern porch was built by the aisle. Both new parts must have been built in the early Gothic style, i.e. with a pointed portal, larger pointed windows and pointed arcades opening onto the crossing. Following the example of other buildings of that period, large windows could have been placed in the gable walls of the transept. Presumably, older windows in the nave, aisle and chancel were replaced, with triads of narrow lancet openings in the western wall of the nave and the eastern wall of the chancel.

At the earliest in the early 14th century, or at the latest towards the end of that century, a magnificent quadrangular tower with a height of three storeys was added to the southern wall of the chancel, at the junction with the nave. It was situated unusually for the region, and also lacked elements popular in Pembrokeshire county, such as a batter in the ground floor and a cornice above the plinth. In addition, its upper parts were only slightly tapered in relation to the base. A communication turret was projected from the south-west corner with a shallow projection, but exceptionally, a second, slightly smaller spiral staircase was placed in the north-west corner. The walls of the main part of the tower were topped with a battlemented parapet mounted on corbels projecting from the face. The windows were made very narrow, lancet even on the highest storey with bells. In the late Middle Ages, the tower’s slenderness was enhanced by a tall spire, built of limestone ashlars. The ground floor of the tower was covered with a barrel vault with an opening for the ropes that operated the bells. It was opened to the chancel and the aisle with high pointed arcades.

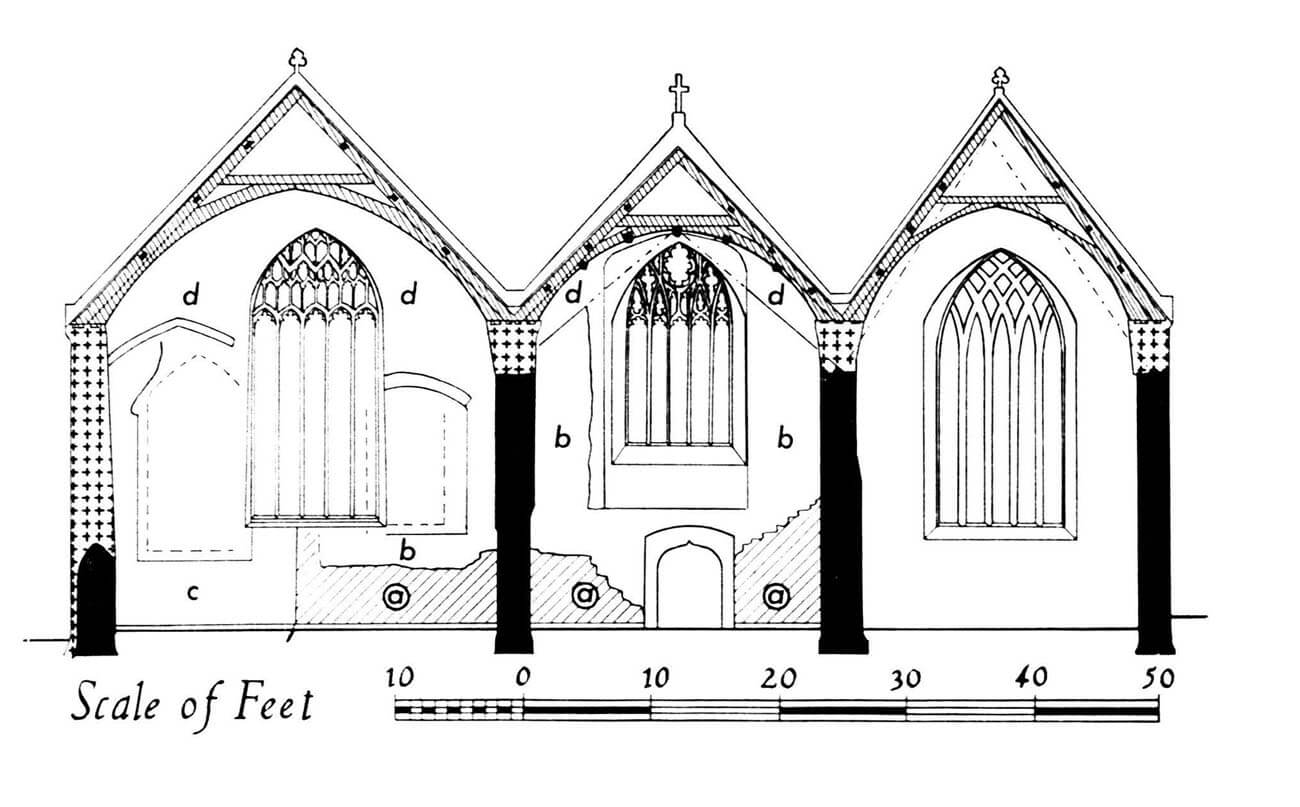

The late Gothic reconstruction significantly enlarged the church and developed its spatial layout. First, at the end of the 14th century or in the early years of the 15th century, a small chapel was built at the southern porch, in line with the western wall of the nave. In addition, a northern aisle was added at that time, similar in width to the nave, covered with a separate gable roof. From the west, it was also in line with the older part of the nave, while in the east it absorbed the northern arm of the 14th-century transept. Inside, the northern aisle was connected to the nave by five pointed arcades. It were set on four pillars, characteristically devoid of capitals and bases, but with rich, continuous moulding from the floor to the archivolts of the arcades. The external entrance to the northern aisle was placed in the portal in the middle bay. On both sides of it, tomb niches were set in the wall.

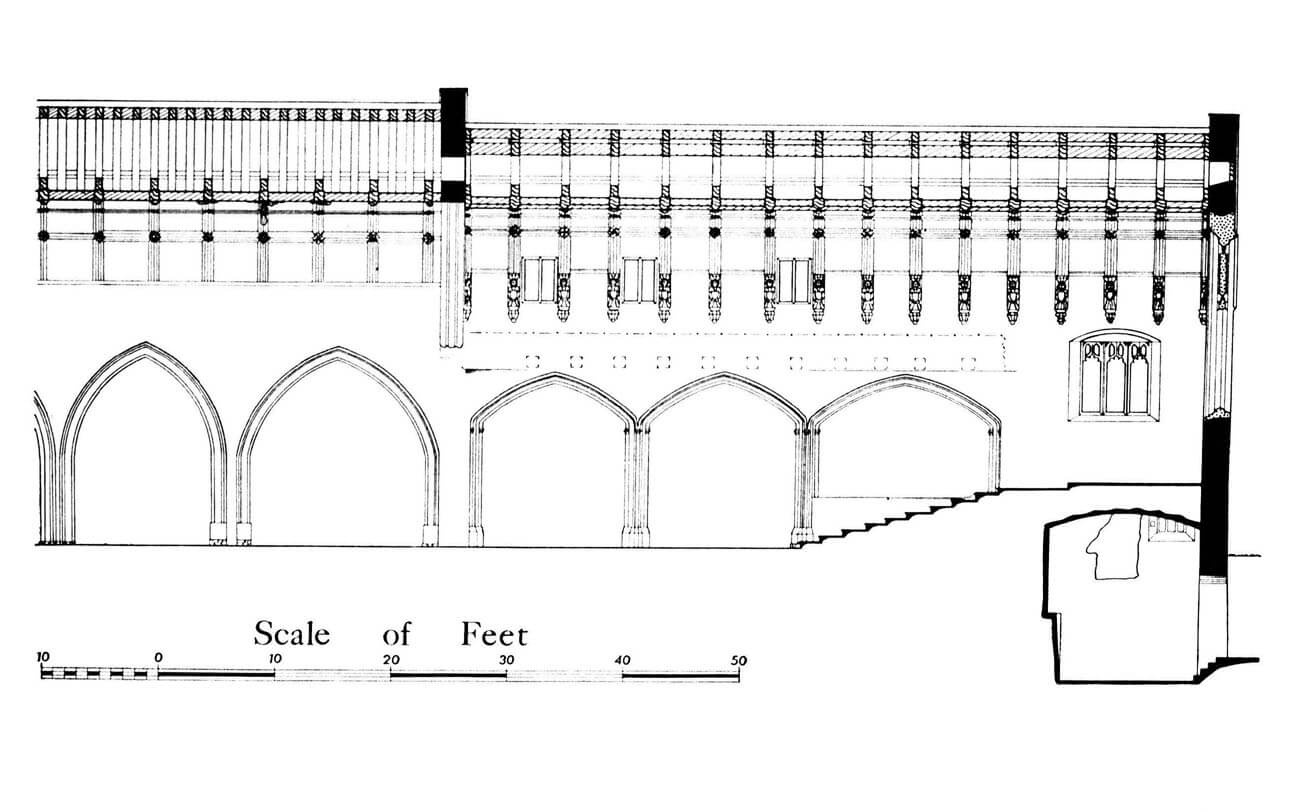

At the beginning of the 15th century, a two-bay chapel was added to the southern wall of the chancel, with a longitudinal wall slightly inclined in plan. From the west, it was opened with a pointed arcade on the ground floor of the tower, while on the chancel with two arcades. Then, after the mid-15th century, the chancel was extended by one bay again from the east side. A chapel was also built at the northern wall of the chancel, created on a trapezoidal plan, due to the short eastern wall and the northern wall placed at an angle to the church axis. Such an unusual plan could have resulted from the need to adapt the shape of the chapel to the older buildings at the church. Its interior was connected to the chancel by three arcades with low pointed archivolts, supported on slender pillars with moulded shafts and polygonal plinths. The chancel itself was raised around 1450 and equipped with a crypt. Thanks to it, the easternmost part of the presbytery had to be accessible from then on by means of 11 steps. Thanks to the raised walls, the chancel accommodated the chapel of St. Anne in the western part of the attic, lit by quadrangular windows of the clerestory. The interior of the chapel and the chancel were covered with a continuous wooden wagon roof placed on carved corbels. A similar semicircular wagon roof covered the nave, differing in thinner frames and the lack of figures on corbels, but decorated with carved bosses at the intersections of the wooden ribs.

At the end of the 15th century, the southern part of the church was thoroughly rebuilt and unified. In place of the 13th-century narrow aisle, the 14th-century porch, the adjacent small chapel and the southern arm of the transept, a very wide southern aisle was created, connected to the tower on the eastern side by an old arcade, and on the western side creating an straight façade with the nave and northern aisle. Shortly afterwards, a rectangular porch was added to the southern wall of the new aisle, probably because of the town hall built on the southern side of the church shortly before. Inside, the wide southern aisle was connected to the nave by five pointed arches, similar to the northern aisle, but with a different spacing of the pillars. The late Gothic aisle was lit by large pointed tracery windows. A particularly impressive five-light window was set in the western wall, replacing two older windows in the 13th-century nave and chapel. Three more windows, probably four-light, illuminated the aisle from the south, on both sides of the porch.

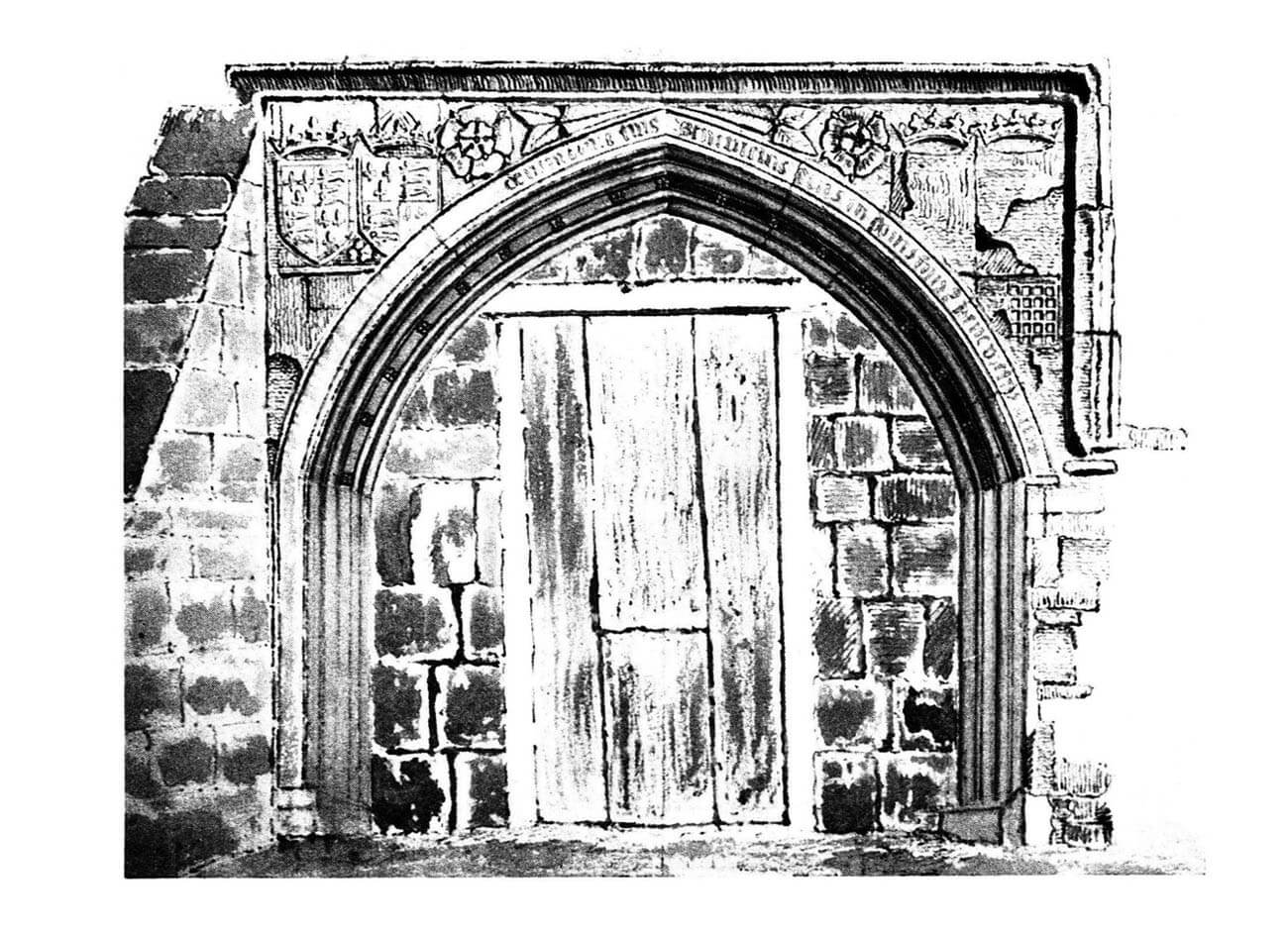

The latest element of the church from the Middle Ages was the unique western porch, built on the plan of an equal-armed cross in front of the nave, where a late Gothic entrance portal was placed, topped with a richly moulded ogee arch with a bas-relief inscription (“Benedictus Deus in donis suis”). The entrance portal to the porch was also moulded, pointed, with a slightly lowered top of the archivolt. Just above it ran a cornice, framing the bas-relief heraldic symbols placed on the sides of the archivolt (the Beaufort family coats of arms, royal insignia, the coat of arms of Jasper Tudor, the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Pembroke).

Current state

Church in Tenby is today the largest parish church in Wales, a testament to the wealth and prosperity of the town in the Middle Ages. Its modern silhouette and layout are the result of centuries of expansion, only slightly erased by the addition of the modern north porch and south vestry, and the demolition of the medieval west porch in 1831. The oldest, 13th-century fragments of the church are in the west wall of the nave and perhaps in the ground floor of the tower. The south entrance portal also dates from this period, while on the axis of the nave from the west there is a 15th-century portal with a bas-relief inscription. The church’s windows were renewed during the Victorian regothicization. Most, like in the north aisle, were replaced with completely new ones, but some only had new tracery inserted. The oldest original windows survive in the walls of the tower, where the medieval spire is also worth noting. Inside the church, a 15th-century wagon roof has been preserved in the nave and in the chancel, including decorative bosses and carved corbels. The vaulted crypt also dates from the 15th century, while the moved piscina is older. In addition, the church has preserved late Gothic arcades, of which only those between the nave and the south aisle have been renewed and partially transformed during early modern renovations. The church’s fittings include a 15th-century font and the tombs of Thomas and John White, mayors of Tenby from the 15th century (Thomas White is famous for hiding the young Henry Tudor from King Richard III).

bibliography:

Barker T.W., Green F., Pembrokeshire Parsons, „West Wales historical records”, 4/1914.

Ludlow N., South Pembrokeshire Churches, An Overview of the Churches in South Pembrokeshire, Llandeilo 2000.

Ludlow N., South Pembrokeshire Churches, Church Reports, Llandeilo 2000.

Salter M., The old parish churches of South-West Wales, Malvern 2003.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, VII County of Pembroke, London 1925.

Thomas W.G., The Architectural History of St Mary’s Church, Tenby, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 114/1966.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.