History

The Strata Florida Abbey was founded in 1164 by the Norman knight Robert Fitz Stephen settled at the nearby Cardigan Castle. Cistercian monks were brought from Whitland Abbey and began building a monastery on the banks of the Afon Fflur River. A year later, the Normans were supplanted by the Welsh ruler of Deheubarth, Rhys ap Gruffydd, who, however, confirmed the granting of land to the Cistercians. In 1184 the location of the abbey was changed to its current place, while the old one was named Hen Fynachlog, which means Old Monastery. In the same year, Rhys expanded the privileges and grant Cistercians almost 80,000 acres of land, taking over the role of the patron and benefactor. Thanks to this in Strata Florida was buried Rhys’s brother, Cadell ap Gruffudd, and then another nine representatives of the Welsh dynasty. After the translocation, in a new place the monastery church was consecrated in 1201, while in 1255 it was recorded the purchase of a great bell, probably hung in the tower at the naves crossing.

The peak of the abbey’s splendor fell at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries. Its resilience is evidenced by the fact that as early as 1179 a group of monks was sent from Strata Florida to establish a branch in Llantarnam (Caerleon), and in 1186 in Aberconwy. The Cistercians dealt in the breeding of cattle and sheep, grazing in the vast grounds of the monastery, managed by numerous granges. Ultimately, their number oscillated around fifteen, being one of the main sources of the abbey’s income. Lay brothers worked in them, who made order vows, but were not admitted to most services and ceremonies because of illiteracy. The monastery was also the spiritual center of the region, managed, unlike many other abbeys, by native Welsh people. The abbots were then Deiniol and Cedifor, next Rhys, Morgan and Dafydd ab Owain, all with Celtic names. Probably thanks to this, in the abbey was created the most important source for the early history of the Wales, the Latin Chronicle of the Princes, and then its Welsh translation Brut y Tywysogion.

Close connections of the abbey to the Deheubarth dynasty aroused suspicion and distrust of English King John. In 1212 he even ordered to destroy the abbey as a “haven for our enemies”. This command was not followed, but the monks had to pay a large sum of £ 800. Strata Florida’s political connections were not limited to South Wales only, because in 1238, the North Welsh Prince of Gwynedd, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, held a council in Strata Florida on which other Welsh leaders recognized his son Dafydd as his legitimate successor.

In the second half of the 13th century, the monastery began to decline. In 1285 it suffered damages as a result of a lightning strike, it was also destroyed and looted several times in connection with the Welsh-English wars of 1276-1277 and 1282-1283. In 1291, the abbey’s annual income was valued at only £ 98, which was the average for Welsh monasteries. Three years later, the scale of the misfortune was increased by the burning of the abbey by the English army during the suppression of the Welsh uprising of Madog ap Llywelyn, despite the fact that King Edward I swore that this was not done at his command. In addition, in the 1340s, a dispute broke out in the decaying monastery over the appointment of abbot, with both Clement ap Rhysiart and Llywelyn Fychan wanting to become one, and shortly afterwards the whole abbey was hit by the Black Death epidemic raging in Europe.

In 1401, in the early years of the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, Strata Florida was seized by King Henry IV and his son. Monks considered as supporters of Glyndŵr were evicted from a monastery, which was than looted. Henry IV transformed the buildings into seat for his troops, planning to defeat all Welsh rebel forces operating in the region. In 1402, the Earl of Worcester was in Strata Florida with a garrison of several hundred archers and infantry, who used the abbey as a base for further campaigns against the Welsh rebels in 1407 and 1415. The ruined monastery was returned to the Cistercians with the end of Glyndŵr’s rebellion, but soon after it was taken over by the armed men of John ap Rhys, abbot of Aberconwy claiming rights to Strata Florida.

The slow reconstruction of the monastery began in the mid-15th century during the reign of Abbot Morgan ap Rhys. The community, reduced to seven monks, survived the first wave of dissolution of the monasteries in 1534 (despite having revenues of £ 118, well below the required £ 200), but the cassation occurred shortly thereafter, in 1539. The church and most of the buildings were dismantled for building materials, such as glass and stone, as well as tiles and lead from roofs. Only the refectory and dormitory were reconstructed as Ty Abaty, a home for the local nobility. Much of the former Cistercian monastic land was handed over to Thomas Cromwell, the first Earl of Essex, who sold it to Sir Vaughan of Trawsgoed. The discovery of the abbey took place again during railway works in the 19th century, when Stephen Williams, a member of the Cambrian Archaeological Association, began digging up the ruins.

Architecture

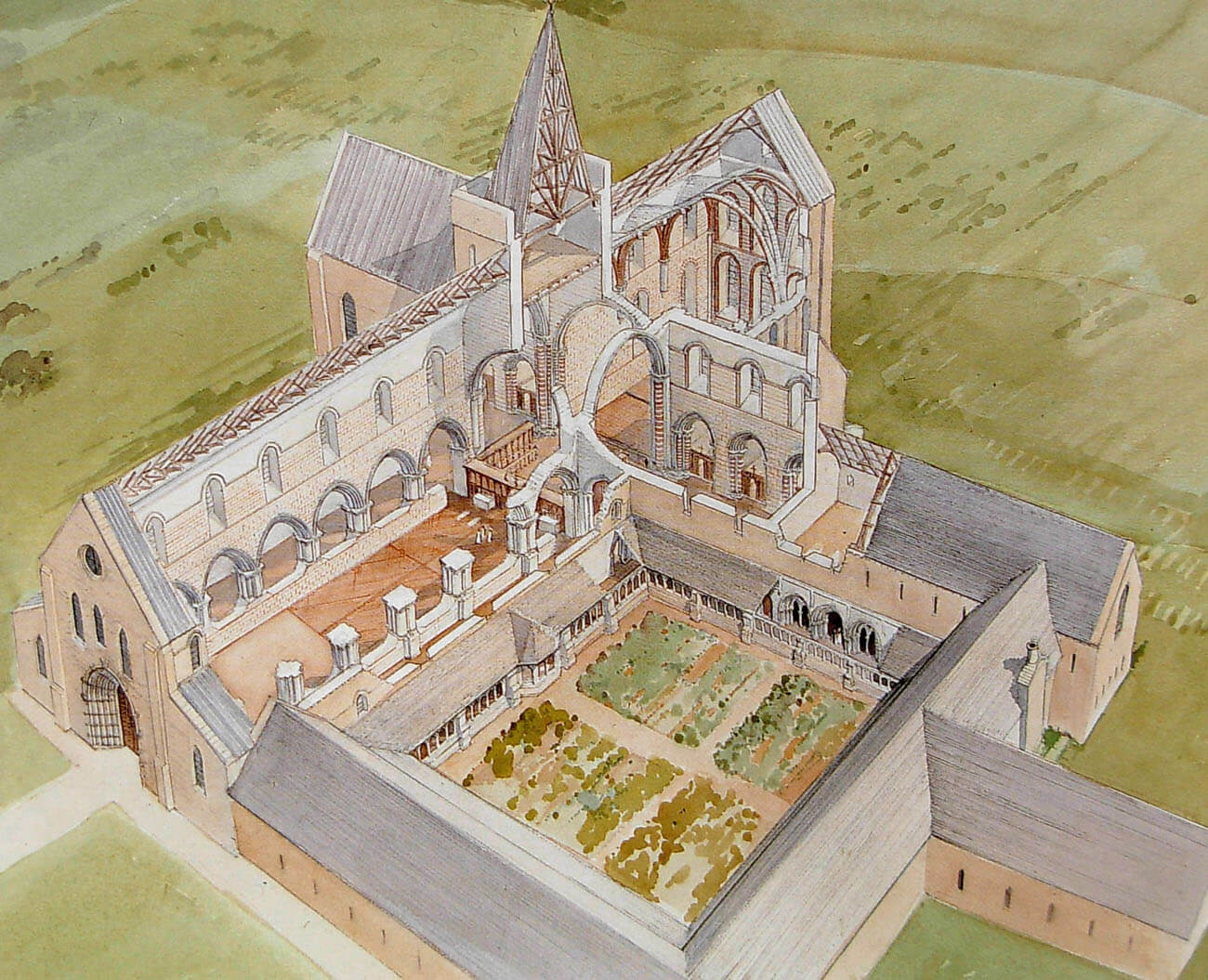

Strata Florida was a typical monastery built according to the Cistercian scheme. After moving in 1184, it was situated among flat meadows bordering the banks of the Teifi river. In close proximity flowed a stream connecting with the river, crucial for ensuring good sanitation. The field in front of it, in the 16th century called Convent Green, was a further part of the abbey’s precinct, surrounded by a stone wall. There was at least one gatehouse within it, and inside, except the main abbey buildings inaccessible to lay people, there were economic houses and rooms for the abbey’s guests. From the most important part of the monastery complex they were separated by another gatehouse, located on the west side of the church.

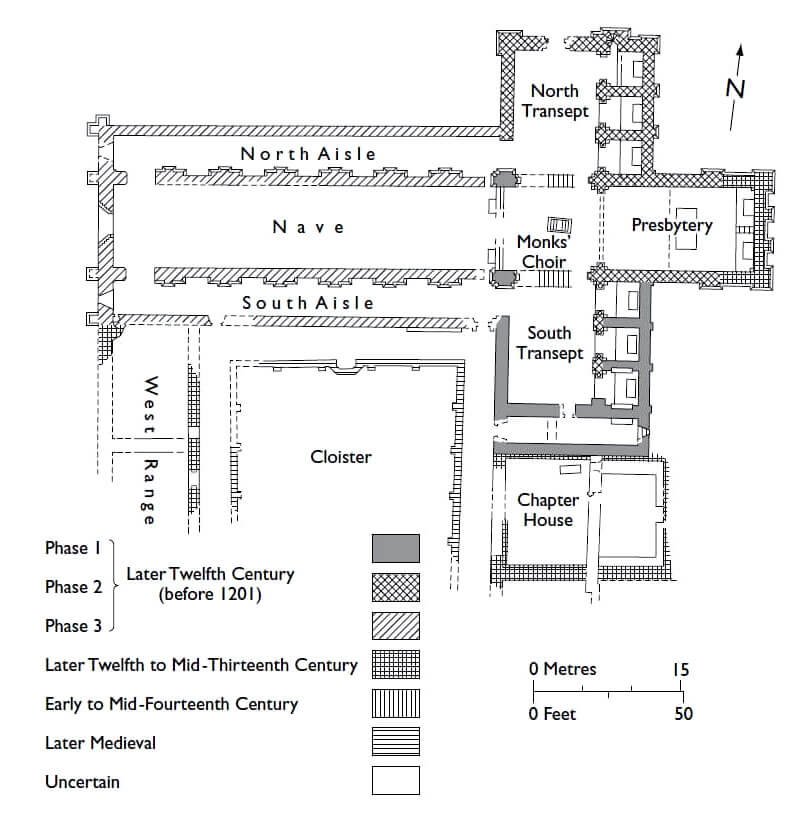

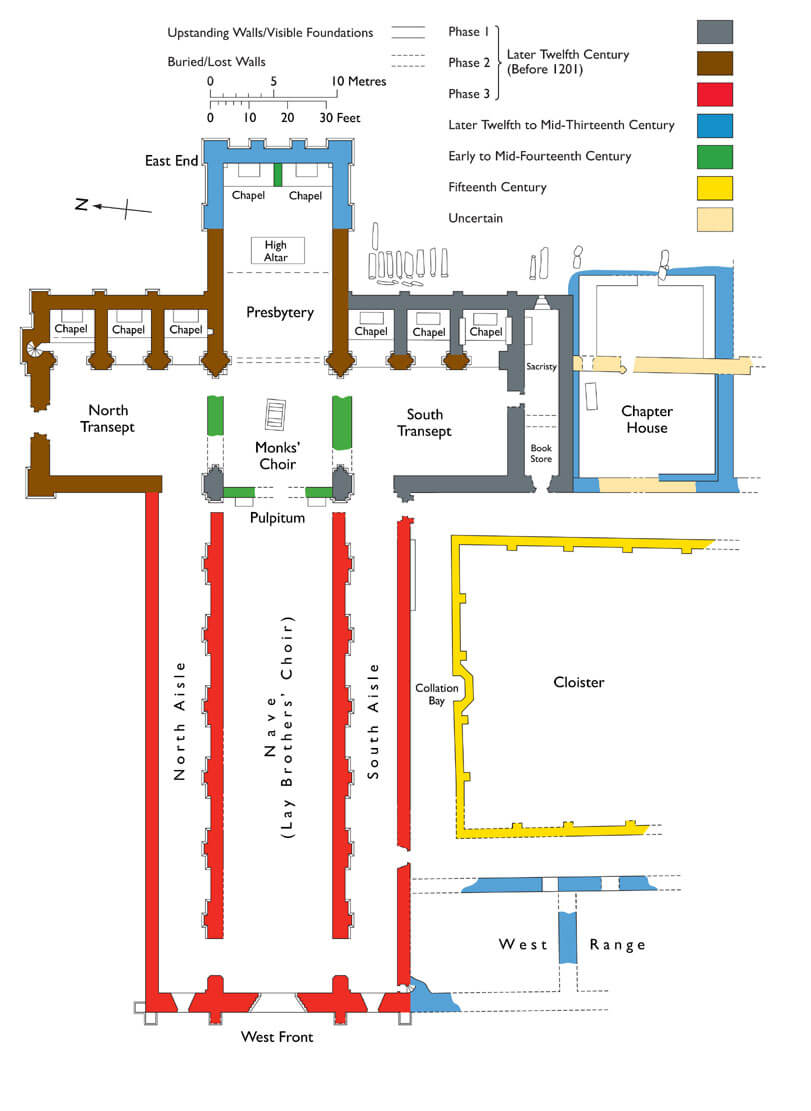

The church was erected as a three-aisle, seven-bay basilica (most probably modeled on the French Fontenay), on the plan of a Latin cross 65 meters long, with the northern and southern transept 35.5 meters wide, rectangular chancel from the east and a low tower at naves crossing. A characteristic feature of the church was the chancel roof, lower than the nave. At its eastern wall there were two small chapels, which were expanded before the mid-thirteenth century. Three chapels were also placed in the eastern parts of the transepts. The construction probably began with the southern transept and its vaulted chapels, moving towards the intersection of the naves and the northern transept, and towards the chancel, which was initially clearly shorter. Its extension towards the east and the establishment of rib vaults was probably decided at the end of the 12th or early 13th century. It is believed that the nave was erected earlier, before the consecration in 1201. The entrance to it led through the main west portal with a form not having any reference to any other Cistercian building in Britain. It was surrounded by six shafts without capitals, but separated by thirteen transverse bands, each of which ended with a scroll and a floral motif. One of the more prominent shafts occupied only the upper part of the portal. Above it, originally the facade was pierced by three narrow pointed windows and perhaps an oculus in the part of a triangular gable. Also, each of the aisles, separated by a high stepped buttress, was lit from the west with an ogival window.

Inside the church, apart from the extreme western bay, the remaining part of the nave was separated from the aisles by 1.5-meter high partition walls. It was a typical solution for Cistercian churches in Britain, but in Strata Florida it was solved in an unusual way, namely, inter-nave pillars were built on the partition walls. They stood out of them in three different forms, forming ogival arcades above. Originally, by the partition walls, stalls of lay brothers were placed, to which they had access through a small spiral staircase in the southwest corner of the church, probably leading to the dormitory. To the east of it, two more portals led to the cloister area. It seems that both the nave and the aisles have never been vaulted, but only covered with a wooden roof truss or perhaps a flat ceiling.

The eastern part of the nave was closed by a rood screen (pulpitum) after which a stone base has survived. The portal placed in it led to a centrally located choir, surrounded from north, south and west by monks’ stalls. Four ogival arcades of the naves crossing towered above choir, above which was a four-sided tower. It was at these benches (stalls) that the brothers gathered seven times a day and at night to pray and sing. In the middle of the choir’s floor was an unusual basin with stairs on two sides, probably intended for the abbot’s washing ceremony of the brother’s feet. Basin was connected to the outflow that ran through the entire monastery, which chute was probably near the stream.

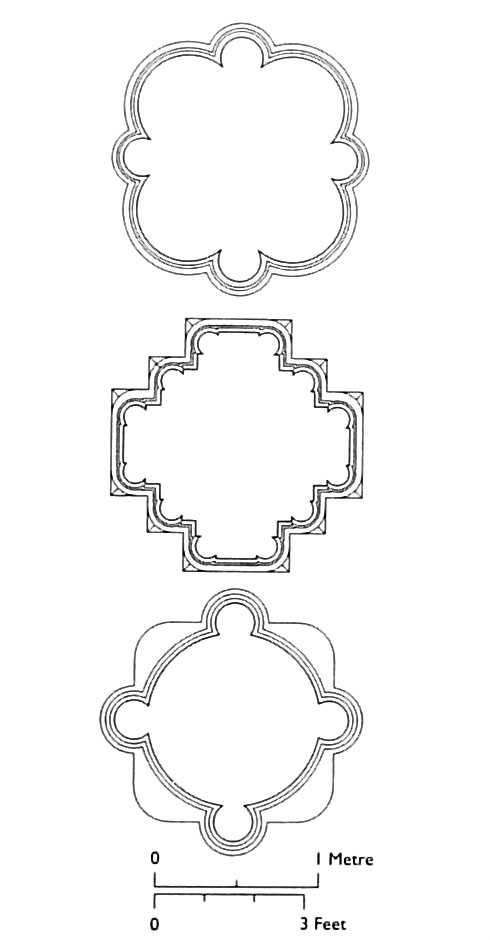

The four-sided presbytery had the width of the central nave and three bays of rib vault supported by wall columns, lowered in the corners to the floor, and on the sides suspended on corbels. Its floor and the floor of adjacent chapels was paved in the fourteenth century with richly decorated tiles, some of which had decorations in the form of griffins, flowers, leaves, crosses and heraldic shields. The less important nave and aisles had floors of local slate. The vault above the presbytery also received a sophisticated form, its ribs were decorated with the motif of “pellet” painted in red and black. The eastern wall of the presbytery was pierced with two or three rows of narrow ogival windows, placed between the side buttresses. For a change, western and eastern windows in transepts had a semi-circular form. Below them, in the east, ogival arcades opened to the vaulted side chapels, with steps at the bottom, probably providing the basis for wooden screens. The vaults of the transept chapels were based on carved corner corbels and fastened with leafy bosses in which iron pins were used to hang the lamps. The northern wall in the transept was pierced with a richly decorated portal leading to the church cemetery and by stairs placed in the thickness of the wall leading to the attic and perhaps to the tower. On the opposite side the so-called night stairs led to the main dormitory on the east wing floor, and the ground floor portal led to the sacristy.

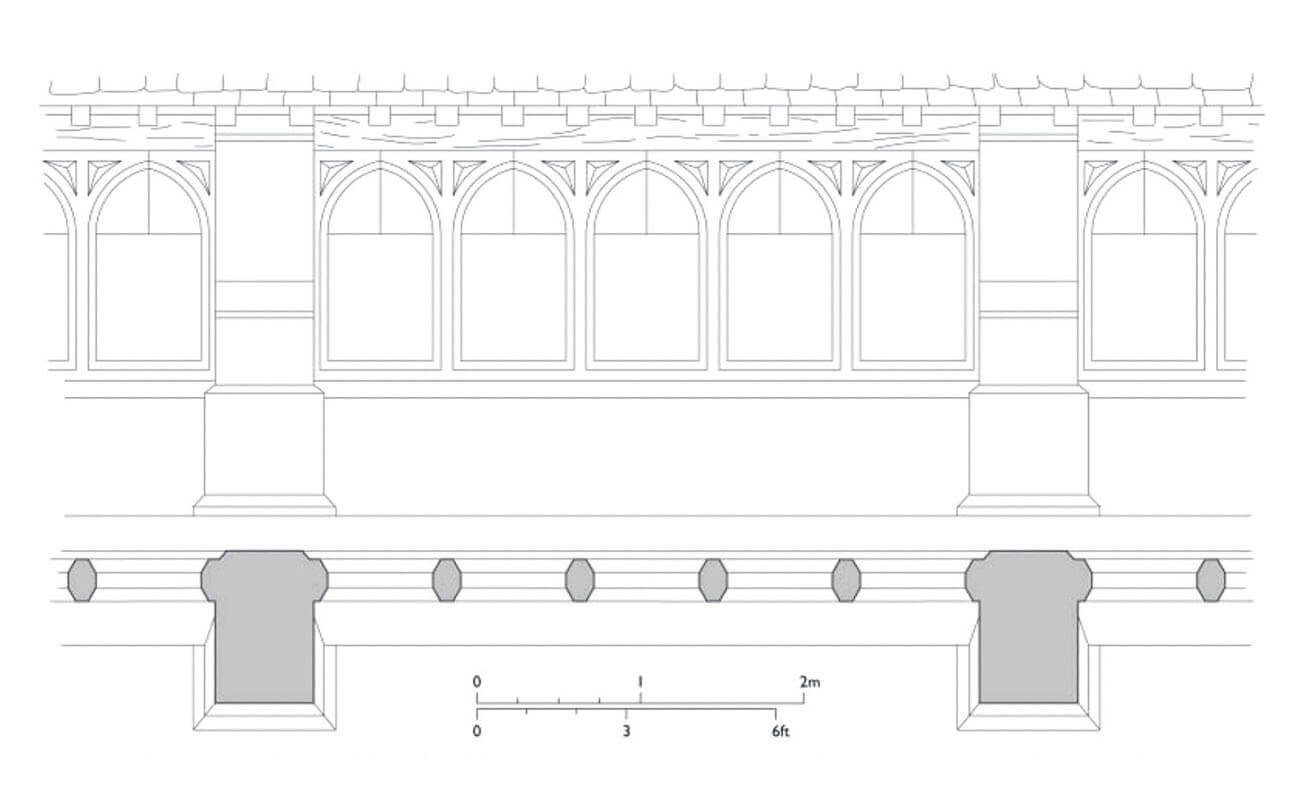

On the southern side of the nave, an inner courtyard was located with side lengths of 30 meters, intended for the garden, surrounded by cloisters enabling movement around the abbey without the need to go out in the cold or rain. Originally, the cloisters were separated from the courtyard by open arcades based on pillars. In the fifteenth century, they were rebuilt, the arcades were replaced by walls with groups of five ogival windows, each group flanked by buttresses protruding towards the courtyard, which certainly better protected from the winter cold. In the northern part of the cloister there was also added a polygonal niche, or alcove, used as a lectern to read before the last service of the religious day (collation). At that time, the brothers gathered on stone benches added to the wall from the side of the church.

A narrow sacristy and chapter house were located on the ground floor level at the southern transept. On the upper floor there was a dormitory and probably latrines, located somewhere along the outflow that crossed the entire monastery complex. The sacristy was originally divided into two rooms, of which the western probably was a small book room (armarium), and the eastern, illuminated by a single window, a room intended for storing vestments and liturgical vessels. In the neighboring chapter house, the brothers gathered every morning, sitting on benches along the four-sided walls, where the matters of the community were debated, monks were tried, and the abbot’s orders were heard. The chapter house was probably built in the 12th century, and in the 1220s it could have been enlarged on the eastern side. In the fourteenth century, however, it was reduced by half, and at the same time increased, perhaps after the damages caused during the Welsh uprising of 1294. Probably the eastern, cut off part was occupied by the tombs of the abbots. The entrance to the chapter house led from the cloister, through the 13th-century ogival, richly moulded portal, flanked by two high, moulded arcades. It was quite a typical solution for Cistercian abbeys.

In the south range in Cistercian monasteries, most often from the east there was a warming room, that is a room heated every day in winter, and from the west a kitchen. The refectory, the place where meals were eaten, was between them, most often protruding perpendicularly outside the compact building complex. The west wing had two floors for lay brothers. At the ground floor level there was a day room and refectory, while on the first floor a dormitory. The ground floor could also have storage rooms and pantries, as well as a parlour, in which conversations with secular guests and the abbey’s visitors were conducted without breaking the monastic rule. Farther away from the enclosed buildings, the infirmary was located in the south-east, where the sick and old brothers stayed. During the cassation period in the 16th century it was in a state of ruin.

Current state

Only the outlines of foundations and the lower parts of the church walls and the northern part of the monastery buildings with the cloister and chapter house have survived to the modern times. Today there is a farm building in the area of the former refectory, and gardens were created on the site of the western part of the abbey. One of the most interesting details is the preserved western portal, once the main entrance to the monastery church, and decorated floor tiles. Above the southern part, where the refectory was once located, a house was built in the 17th century. The area of the abbey is open to tourists.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Harrison S., Robinson D.M., Cistercian Cloisters in England and Wales Part I: Essay, “Journal of the British Archaeological Association”, 159 (2006).

Platt C., Robinson D., Strata Florida Abbey, Talley Abbey, Cardiff 1998.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.