History

St Davids was founded by David, later the saint patron of Wales, in the second half of the sixth century, as a small monastery convent (originally called Mynyw, or Latin Menevia), famous for the ascetic life of the monks. By the eleventh century, St Davids had grown into a very important place of worship and scholarship center, despite being plundered repeatedly by Viking invasions. The reputation of St Davids was so great that at the end of the 9th century King Alfred brought from there the monk Asser, who was to help rebuild culture at the court of Wessex after the destructions inflicted by the Danes. In the second half of the eleventh century, St Davids was the seat of Bishop Sulien, one of the most outstanding Welsh scholars from before the Norman invasion, while his son became the author of the oldest surviving life of Saint David.

Viking raids have repeatedly destroyed St Davids. During them, at least two bishops died, including Morgeneu, whom the Vikings killed during the 999 armed expedition. Living here monk at the end of the eleventh century and the beginning of the twelfth century, described in the life of St. Caradog, that the monastery was deserted at that time, and the ruined buildings were overgrown with vegetation. It was only with the arrival of the Anglo-Normans that St Davids achieved some political stability and protection. In 1115, they appointed a bishop Bernard and attempted to protect St Davids, building a earth-timber motte and bailey castle, later replaced by a stone defensive wall surrounding the entire cathedral complex. Bernard proved to be an effective diocese reformer, but also defended the old rights and privileges of Menevia. At that time, the bishops of St Davids were not only spiritual leaders who appointed priests and supervised church affairs, but also had to settle disputes and manage vast estates. The diocese took over the border regions, so the bishop was also the Lord Marcher responsible for maintaining peace and acting as a military commander if necessary. The Marcher Lords were trusted allies of the English monarch and in exchange for their military assistance, they received extraordinary permissions in their regions. Among other, the bishop organized the weekly and annual fairs in his estates, the fees of which were the main source of income for the diocese.

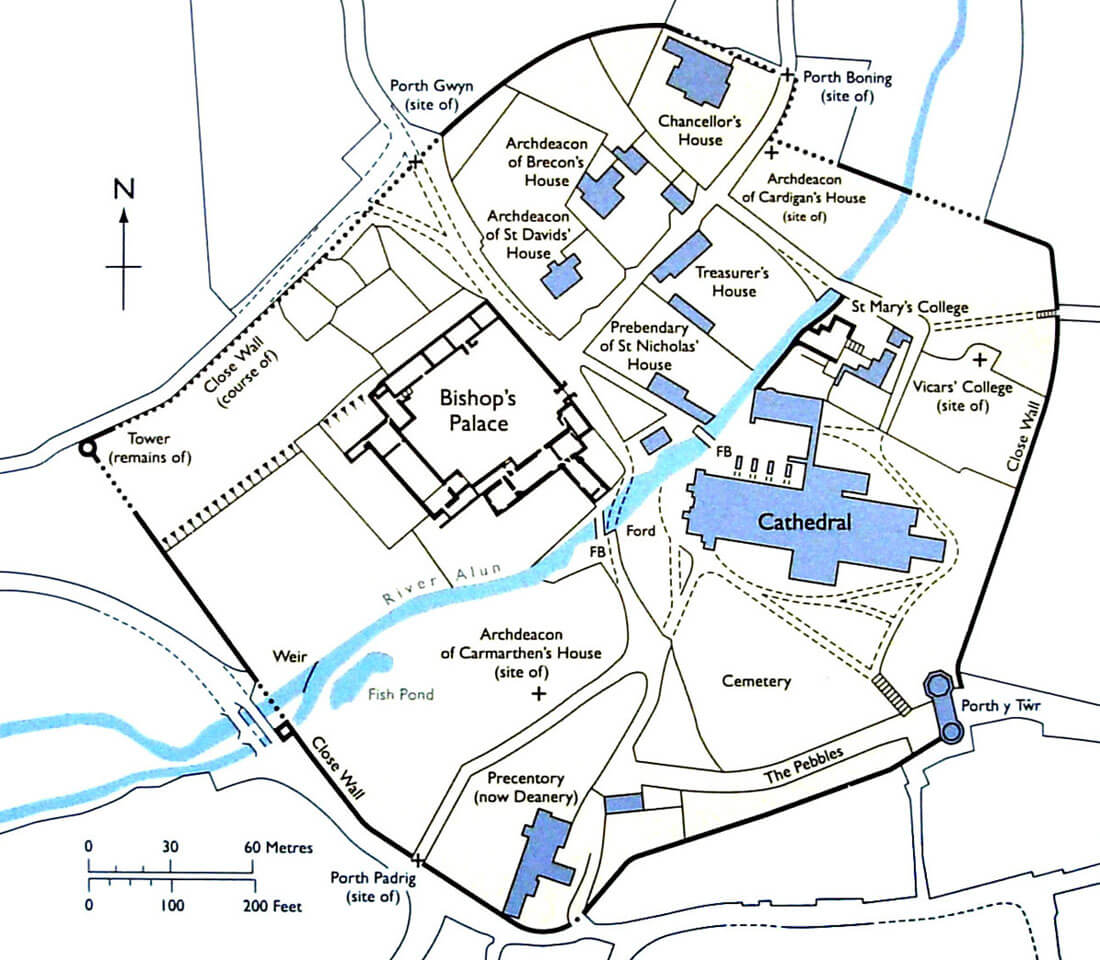

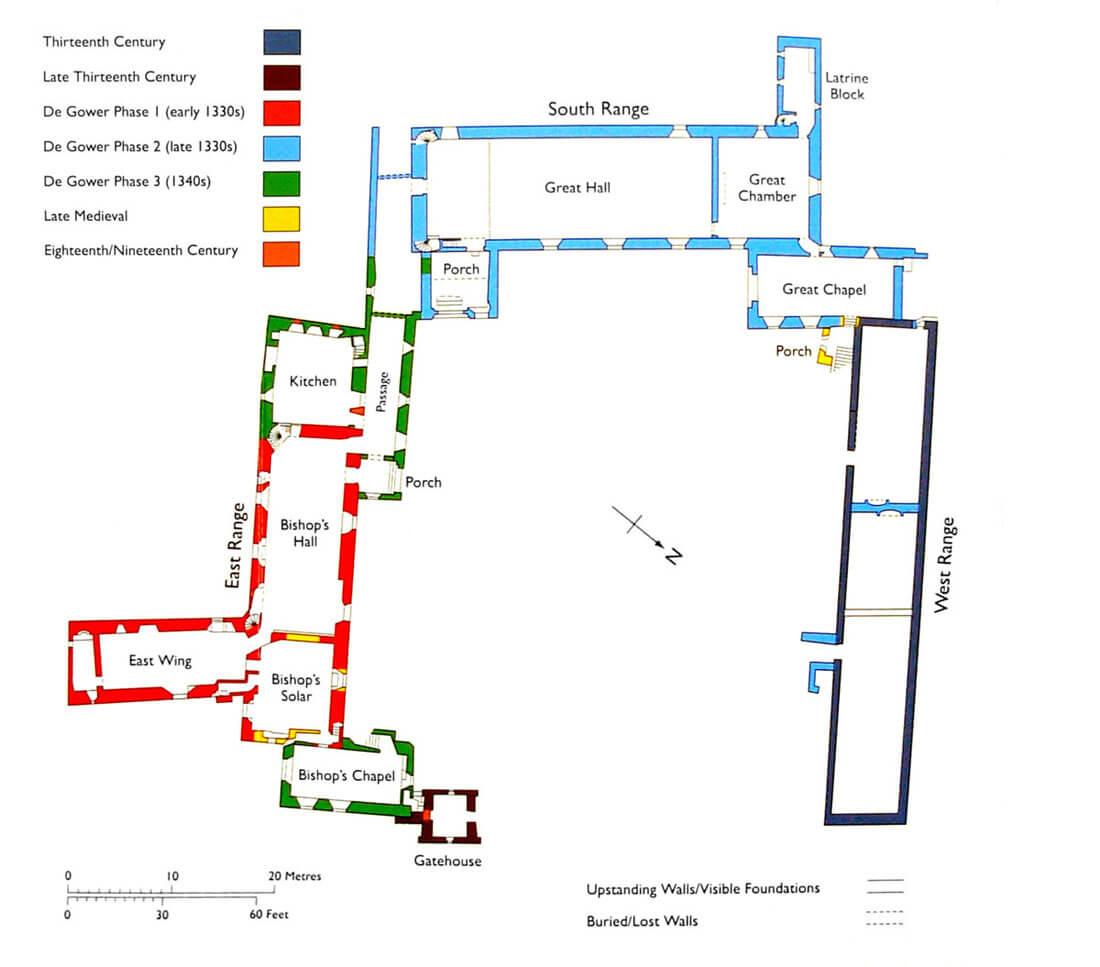

The date of erection, exact location and appearance of the oldest episcopal buildings are unknown. We only know that in 1171 Bishop David Fitz Gerald hosted the English King Henry, who again stayed in St Davids a year later after returning from Ireland. He was then to meet by the canons at the White Gate, which would indicate the functioning of the fortification circuit at that time. In 1188, when Gerald of Wales, a Welsh monk, chronicler, linguist and writer, along with Baldwin, the archbishop of Canterbury, traveled the country seeking support for the Third Crusade, it was noted that they were well hosted in St Davids by Bishop Peter de Leia. The construction of the parts of the palace that have survived to this day was started by Bishop Thomas Bek in the 80s of the 13th century. On his initiative, probably the west range, the gate with the defensive wall and a free-standing belfry (later incorporated into the Porth y Tŵr Gate) were erected. Bek also reorganized the cathedral chapter and in 1287 ordered the canons to surround their homes with walls, but it is not known whether this meant fortifying each property separately or surrounding the entire cathedral complex. As St Davids was a pilgrimage site and a sanctuary in which relics were kept, such a wall must have existed much earlier.

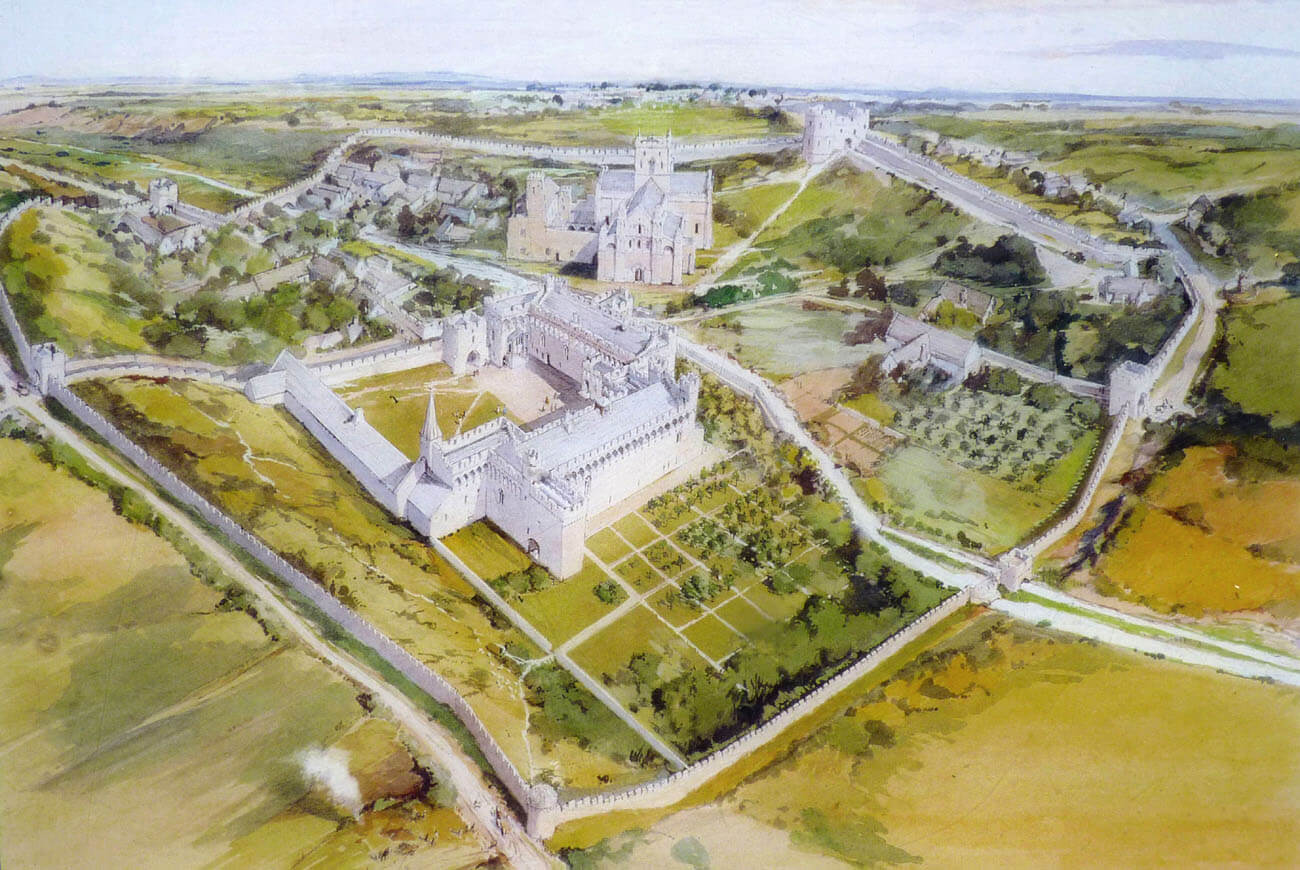

In the first half of the fourteenth century, construction works on a much larger scale was carried out by Bishop Henry de Gower. On his initiative, many ruined buildings were demolished, of which the building material was allocated for new ventures. At that time, the building of the great hall in the southern range was built and the two older wings were completely rebuilt. More unknown work also continued at the outer perimeter of the walls, which was probably enlarged and strengthened. Since the death of Bishop Gower in 1347, probably no major construction works have been carried out at the palace, except for the repairs of Bishop Adam de Houghton in 1362-1389. Within the cathedral complex, he financed only the building of the college and chantry chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary along with the cloisters on the north side of the cathedral.

In the fifteenth century, despite the magnificent palace, the bishops spent less and less time in St Davids. They came here mainly for great feasts during Easter and other major holidays. It is known that in 1398 a great festival in the palace was organized by Bishop Guy de Mone, inviting crowds of canons, clerks, officials and episcopal members of the household. Despite the increasingly rare visits of bishops, the palace was, however, kept in good condition throughout the end of the Middle Ages and staffed with service and employees.

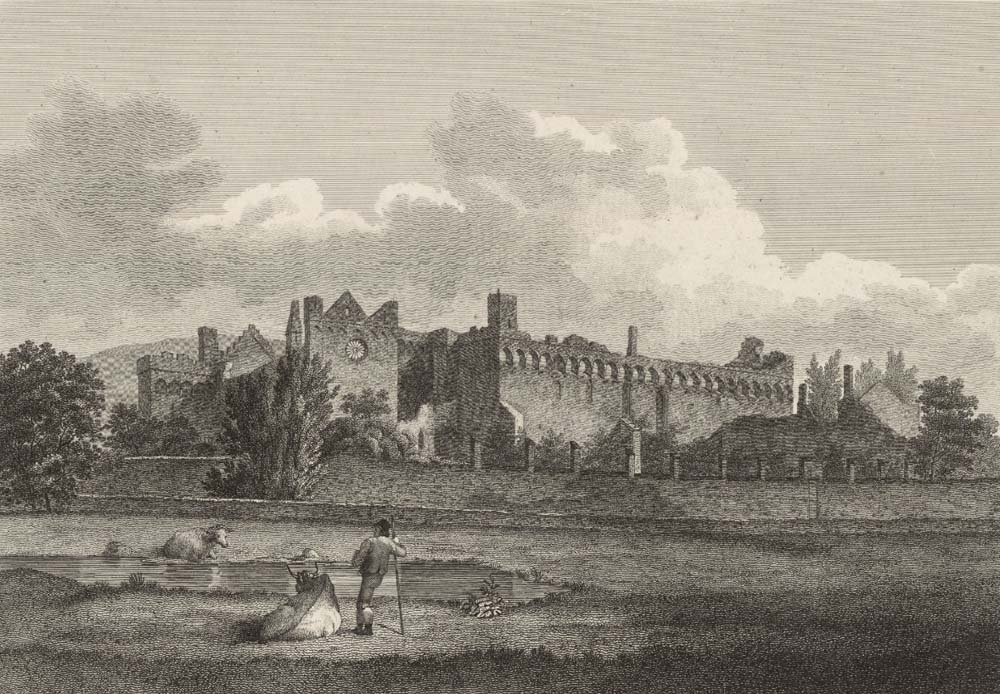

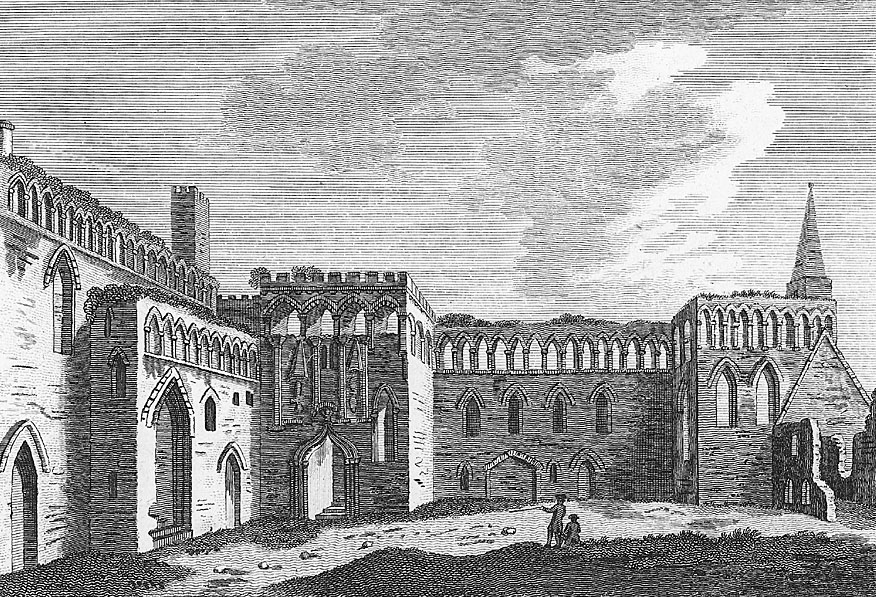

In the mid-sixteenth century, the main bishop’s residence was already in Abergwili, and financial difficulties meant that bishops could not afford large buildings in remote regions of the diocese. The Reformation contributed to this, and the subsequent decline of St Davids as a pilgrimage center. In 1536, Bishop William Barlow, the first Protestant bishop of St Davids, dismantled the roofs of the building, according to tradition, to pay for the wreath of his five daughters (in fact none of them were born yet). Apparently, he made so much money from it that more than twelve years of income from the bishopric would be needed to cover the cost of repair. Unfortunately, due to demolition, the palace fell into ruin, although in the middle of the 16th century bishop Robert Ferrar lived in one of the preserved buildings, like Richard Davies in 1564 and Marmeduke Middleton at the end of the 16th century. In 1616, Bishop Richard Milbourne applied for the demolition of some buildings, and although these works were not carried out for the most part, the buildings were considered irreparable and remained as a permanent ruin.

Architecture

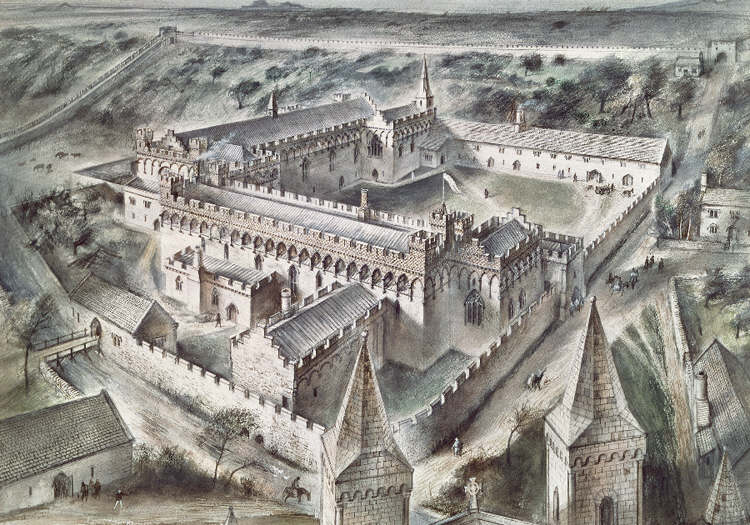

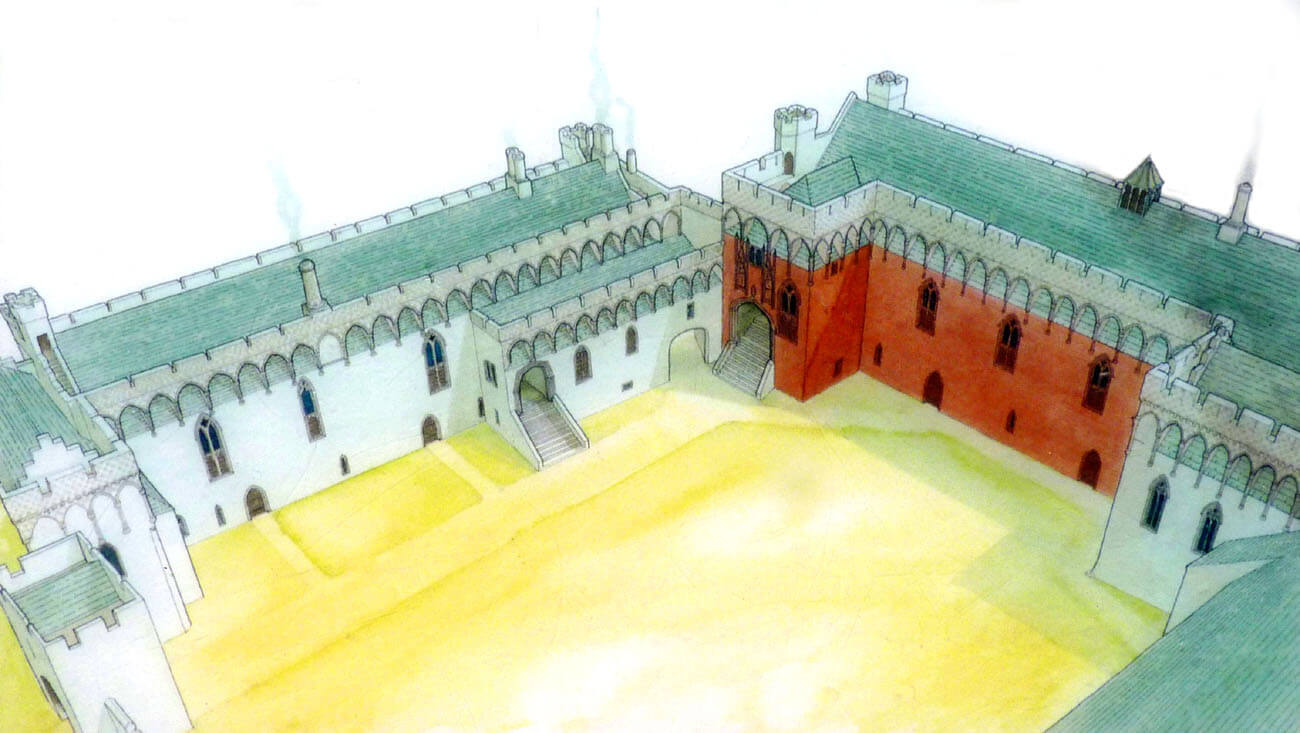

The bishop’s palace after the extension carried out in the first half of the fourteenth century by Bishop Henry de Gower, consisted of three main ranges: on the south, east and west sides, which defined a spacious inner courtyard, enclosed from the north by a defensive wall. The entrance to its area led through the northern, four-sided, three-story gatehouse from the end of the 13th century. In the further distance the wall surrounded the entire palace complex with gardens and orchards, and connected to the outer defensive circuit protecting St Davids.

The entire cathedral complex occupied an area of 6.5 ha surrounded by a 1100-meter long defensive wall equipped with battlement. Originally four gates led into its boundaries: Porth y Tŵr (Tower Gate), Porth Padrig (Patrick’s Gate), Porth Boning (Boning’s Gate) and Porth Gwyn (White Gate). Porth y Tŵr was erected next to the older free-standing octagonal belfry, which eventually formed a two-tower gatehouse with a central, large passage and a smaller pedestrian gate. The room along the gateway served as a bishop’s prison with a descent to a narrow dungeon, while the room and chamber above were used by the city council and the mayor. In addition to the gatehouses, the defense was strengthened by a cylindrical corner tower on the west side and a four-sided tower on the south-west side, provided with sluice over the Alun River. This river flowed through the center of St Davids, dividing it into two parts with the cathedral in the east and the bishop’s palace in the west. Inside the main perimeter were also smaller walled buildings, e.g. the College of the Blessed Virgin Mary founded in 1377, or the Vicar’s College, each with its own chapel and residential buildings.

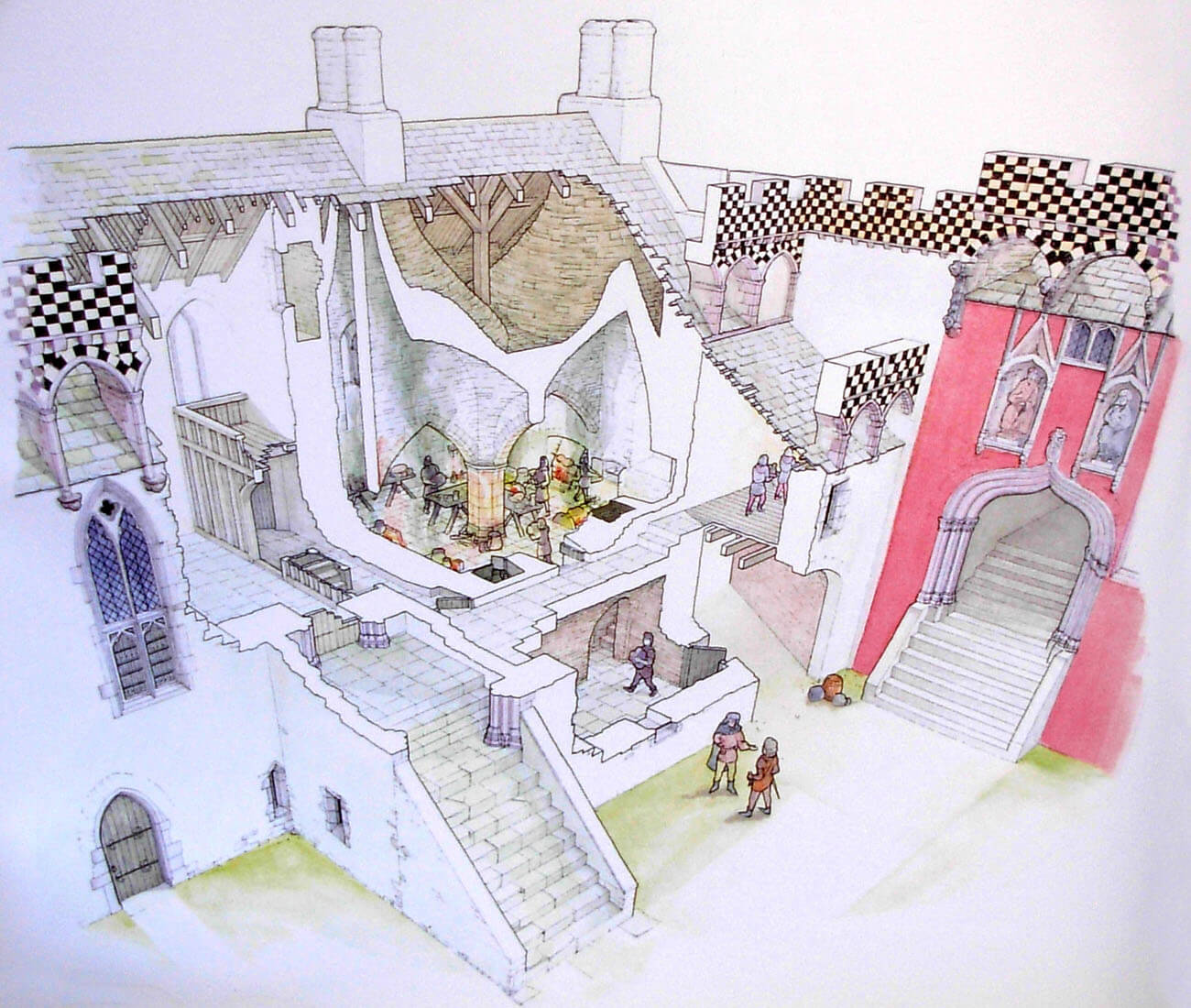

The southern part of the east wing was occupied by a kitchen, erected in the last phase of the construction works of Bishop Gower. It received an irregular layout due to the incorporation of older buildings into its walls. Storage rooms were located in the lower, vaulted storey, while the upper one was divided into four quarters with low stone arcades. They were supported by a centrally located octagonal pillar. The vaults were integrated in an interesting way with the hoods of two side hearths, through which smoke, heat and smells escaped into two chimneys. Kitchen windows were placed high in the walls so that the light fell on the workplaces, and a niche was placed in the eastern wall, maybe a kind of stove or drainage for waste. In addition, cupboards for dishes were created in the walls and an opening in the eastern wall through which dishes were served to servants from the hall.

Opposite to the kitchen, the eastern range was occupied by the bishop’s private chamber (solar), intended for meetings between hierarchs and the close friends. An almost square space in the plan was heated by a fireplace in the northern wall, and was lit by two windows of the same shape as in the hall, with jambs decorated from the inside with delicate shafts and capitals. The portal in the eastern wall led to a latrine placed in the thickness of the wall. In the late Middle Ages, the chamber was transformed by inserting a new upper floor separated by a flat, wooden ceiling, thanks to which some of the windows from the courtyard side were blocked. Access to it led through the same staircase, which provided access to the dais canopy in the hall.

To the bishop’s private chamber and partly to the hall was attached a perpendicular wing protruding to the south-east from the building complex. It was slightly lower and was not crowned with a parapet with decorative arcades. Instead, it had a stepped gable at the short side and a decorative battlement crowning at the longer sides. In its upper floor, there was probably a bishop’s bedroom, warmed by the fireplace, from which the staircase led to the canopy dais in the hall, and the portal in the partition wall led to the latrine located at the end of the building. It was equipped with a kind of cylindrical chimney, which was in fact vent of the latrine pit. On the opposite side, the portal led to a wall-walk in the crown of the perimeter wall.

All the representative and residential rooms described above were located on the upper floors. All of them below also had vaulted undercrofts. Divided into many rooms, they were connected to the upper floor by means of staircases and directl by ogival portals with a courtyard. Inside, the cool temperature provided good conditions for storing food and drinks.

On the north-east side, in the mid-fourteenth century, a rectangular building was erected next to the entrance gate identified with the private chapel of bishops. This is evidenced by its orientation on the east-west line, full glazing of all windows and the lack of a fireplace. The wooden ceiling was supported on alternating large and small corbels, carved in the shape of human heads. The altar was probably placed below a large window in the east wall, and the entrance originally led through the external stairs from the courtyard.

Erected in the years 1327-1347, the southern range was the greatest and largest in the palace complex, serving ceremonial, representational and entertainment functions. It consisted of a rectangular, two-story building and a large entrance vestibule from the courtyard side. Around 1350 a small latrine block was added to it in the southwestern part. Like the eastern range, the southern building was crowned with arcades running along its entire length, decorative battlement and three corner turrets. The latter were accessible by stairs and may have been used to trumpet or other ceremonial greeting of guests by the service. The vestibule and the northern facade of the southern range were the most elaborately decorated part of the palace in the style of English Decorative Gothic, as the first buildings visible after crossing the palace gate. Their facades were covered with red paint, crowned with arcades with figural corbels on two levels, and the parapet was covered with a chequerboard pattern of yellow and purple stones. The vestibule portal received a ogee form with vine ornaments running through moulded jambs. The leaves were also decorated two capitals and the central top of the portal, above which were placed two niches with gables, originally housing statues.

The ground floor of the southern building was divided into six rooms with utility functions. On the first floor there was a great hall and a large chamber in the western part. The great hall was an impressive room, 27 meters long and 9 meters wide. The whole was topped with an open roof truss with an apex towering over 12.5 meters high above the floor. Near the entrance, a staircase in the thickness of the wall led to the gallery in the crown of the building, and subsequent passages led from the corners of the hall to the lower floor. Between them, the portal led to the gallery leading to the kitchen in the east range, from where the servants brought dishes and drinks. It is worth noting that all the portals in the back of the building were hidden behind a wooden, decorative partition screen. On its opposite side there was a dais – a podium, for the most important revelers, illuminated with the entire hall by three large windows from the courtyard side and one from the gardens side. It had a similar form to the windows from the east range, but were devoid of delicate shafts at the internal jambs. In addition, a decorative rosette with a central quatrefoil and external curvature was placed in the upper part of the western wall, used to look perfectly round due to the view from below. The walls of the great hall were originally covered with plaster, perhaps in the Middle Ages decorated with paintings or tapestries. A long, blank southern wall would be particularly suitable for this. The lack of a fireplace in the great hall means that originally an open, central hearth had to function here, whose smoke escaped through the louvred chimney in the center of the roof.

The great chamber in the western part of the south range served as a private room and bedroom for the most important guests, and perhaps as a place of temporary seclusion from public ceremonies in the great hall. It was well lit by individual windows in each of the three external walls and warmed by a fireplace. The portal in the southwest corner led from it to a small annex with latrines in which a cylindrical staircase in the thickness of the wall led to an alcove similar to that in the east range.

The Great Chapel building adjoined the corner of the southern range, accessible through a diagonal passage in the wall in a great chamber. Originally, there was no other entrance to the chapel, and the oblique passage was closed with a door with a lock. It was not until the end of the Middle Ages that the ogival portal was opened and a porch was added from the courtyard side. The altar was located under a large, ogival, three-light window in the eastern wall, flanked from the outside by niches with statues placed in the jambs. Inside, on the right, there was a Gothic piscina, decorated with two pinnacles, a vine ornament, an ogee arch, and equipped with a drain for water. The chapel was illuminated by vivid colors from window stained glass and wall polychromes. Sounds were provided by two bells hung in a four-sided corner belfry, moved by ropes through two square holes. The back of the chapel was occupied by a sacristy, and in its ground floor a large, well-lit, vaulted chamber had access to the latrine in the back. It probably served residential purposes for the servants.

The smallest west range, which dates back to the early 13th century, was a two-story, long and narrow building, probably having economic functions. In the ground floor in the fourteenth century, a stone barrel vault was inserted, and at the level of the floor two longitudinal rooms were situated. Two fireplaces were placed in the wall that separated them, one for each room. On their sides were stone brackets for lamps. From the room closer to the Great Chapel, the passage led to the latrine situated behind it. The whole seems to be used to accommodate less important guests, reminiscent of a large dormitory. The lower floor was equipped with a well and served economic functions.

One of the characteristics of the St Davids bishop’s palace was the set of almost two hundred carved corbels mentioned above. Among them you can separate several groups: with human heads, animals and mythical creatures. Human heads were placed first of all in the episcopal hall, where they supported the roof truss and dais canopy, the bishop’s private chamber and the chapel, where small and large heads were arranged in turns. Among them were a few female heads, and men received various hairstyles and beards, although without individual facial features. Until the 30s of the 14th century, similar heads were also used in the rooms of the southern range and from the outside under arcades and a parapets. The outer corbels for a change consisted mainly of representations of various animals (lions, monkeys, baboon, dogs, cats, owl), while hybrids, monsters and various beasts were carved on the eastern range. Perhaps bishops wanted to achieve the effect of a gradual transition, when the guest after entering the courtyard saw mascarons, and as he advanced deeper into the palace and into the episcopal interiors, he watched calmer faces.

Current state

The bishop’s palace in St Davids is one of the most valuable monuments of medieval, not defensive, secular architecture, not only in Great Britain, but also throughout Europe. To this day, it has been preserved practically in its entirety, but in the form of a unroofed ruin. It remains under the protection of the governmental agenda Cadw, which makes it available to visitors from March 1 to June 30, daily from 9.30 to 17.00, from July 1 to August 31 daily from 10.00 to 18.00, from September 1 to October 31, daily at 9.30-17.00 and from November 1 to February 28 from Monday to Saturday from 10:00 to 16:00 and on Sunday from 11:00 to 16:00. In addition, there is a Gothic cathedral within the complex area, fragments of the outer defensive wall have also survived, especially on the north-west, east and south. Its most interesting element is the fully preserved Porth y Tŵr Gate.

bibliography:

Evans W., Turner R., St Davids Bishop’s Palace, Cardiff 2005.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, VII County of Pembroke, London 1925.