History

The original wood and earth castle was probably built in the second half of the 11th century, shortly after the Norman invasion of England in 1066. Skenfrith was then awarded by king William to one of his main supporters, William Fitz Osber, Earl of Hereford. The original builder of the castle is therefore uncertain, it was Fitz Osbern or king William. It is known, however, that it was originally a timber – earth stronghold of the motte and bailey type, which was to confirm the Anglo-Norman rule over the Welshmen. Together with the castles at Grosmont and White Castle, Skenfrith protected the Monnow River Valley, which was an important route from Wales to Hereford.

William Fitz Osbern did not enjoy Welsh estates for too long, as he died in 1071 at the Battle of Cassel in Flanders, and his son Roger de Breteuil rebelled against the king in 1075 and lost his fortune. When the English ruler died in 1135, Welsh rebelled and the new king Stefan reorganized the lands in March, including Skenfrith and its sister fortifications in Grosmont and Whitecastle, back under the Crown’s control. A lordship known as the “Three Castles” was created at that time.

After a period of peace under Henry II in the 1160s, conflicts between the Anglo-Normans and the Welsh erupted again in the following decade. The Mortimer and de Braose families seized further lands in western Wales, leading to a retaliatory attack on Abergavenny Castle in 1182, led by Hywel ap Iorwerth, Lord of Caerleon. In response, the king ordered the fortification of Skenfrith, for which, according to royal treasury records, 43 pounds was spent in 1186. Further repairs and construction work was carried out in 1190, although the castle was likely still a timber structure.

In 1201, king John handed over Three Castles (Skenfrith, Grosmont and White) to Hubert de Burgh. He was a small landowner who became a chamberlain when John was a prince, and when John inherited the throne, he became a powerful royal official. Hubert began to improve his strongholds, but was captured during fights in France. While he was in captivity, king John handed over Three Castles to William de Braose, rival of Hubert. William soon fell into royal disgrace and lost his lands in 1207, but the son of de Braos, also known as William, managed to regain it during the First Baron’s War. After his release, Hubert became Earl of Kent, entered into royal favors and managed again to receive Three Castles in 1219, during the reign of Henry III. During Hubert’s rule, Skenfrith was completely rebuilt, the old stronghold was razed, and a new stone castle was erected in its place.

Hubert lost authority in 1232 and was deprived of castles that were transferred under the command of Walerund Teutonicus, the royal servant. Walerund, during his reign at Skenfrith, built a new chapel at the castle in 1244 and repaired the roof of the fortress. In 1254, the castle and its sister strongholds were granted to the eldest son of king Henry, the later king, Edward and then in 1267 to the younger son Edmund. It was probably during this period that the west curtain, which was threatened by attacks, was strengthened with a tower, which was the only significant modification of the castle’s stone fortifications throughout its history.

Despite numerous Anglo-Welsh wars and a periodic threat, during which the castle was hastily reinforced, Skenfrith was never attacked. After the invasion of Edward I and the conquest of Wales in 1282-1283, the castle’s military significance diminished and no modernization was carried out. It was not until the Welsh uprising in the early 15th century, that Skenfrith was prepared for defense. Eventually, the rebellion was defeated after a few years, and the unused castle until the sixteenth century fell into disrepair.

Architecture

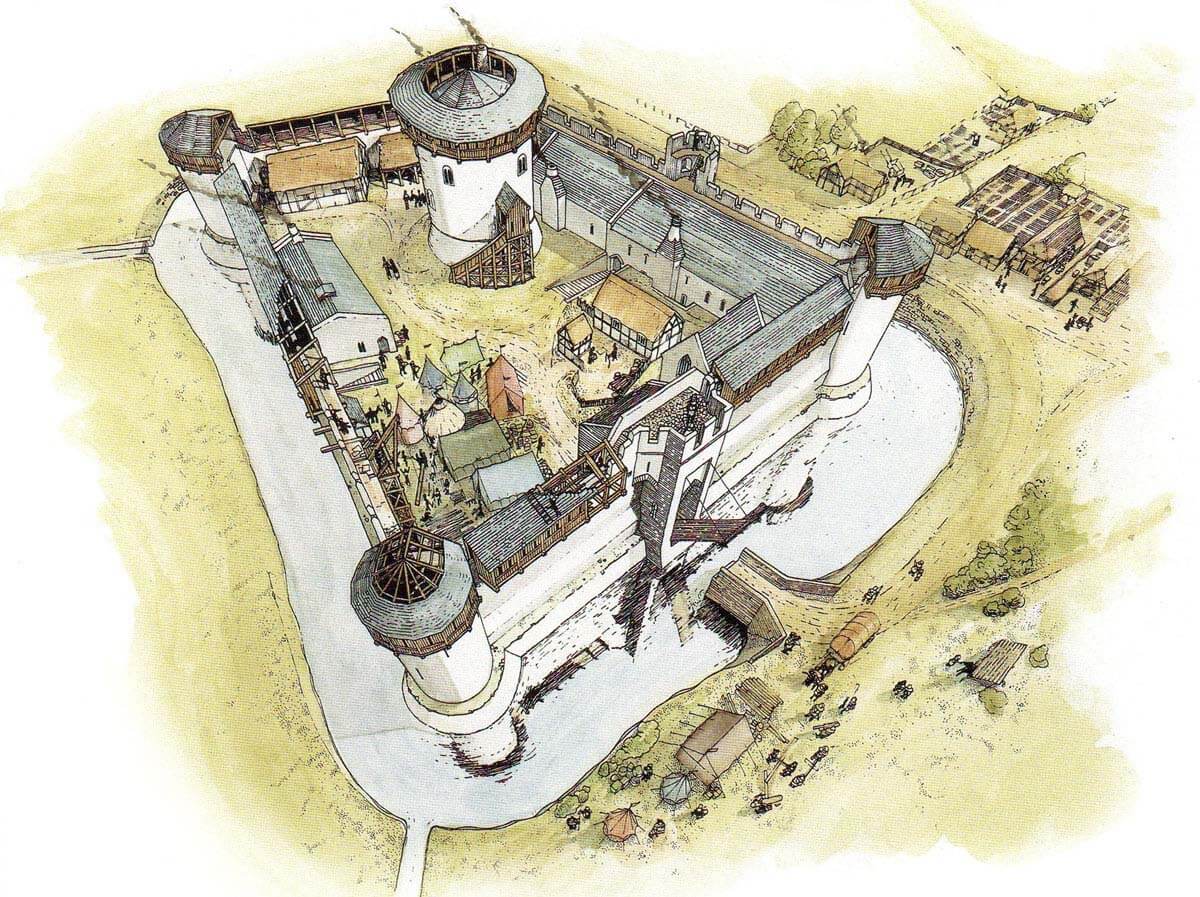

The early 13th-century castle was built on the west bank of the River Monnow, on the outer side of a bend, surrounded by hills several hundred meters away to the north and south. Situated on flat ground, it offered no significant height advantage, but it was able to protect the nearby river crossing and the route that ran latitudinally through the valley on the border between Wales and England. Skenfrith’s main natural defenses were the Monnow riverbed to the east and a smaller stream flowing into it from the north, whose mouth could have been marshy and boggy. Furthermore, the proximity of the river and the lack of elevation differences allowed for the creation of a wide, permanently watered moat.

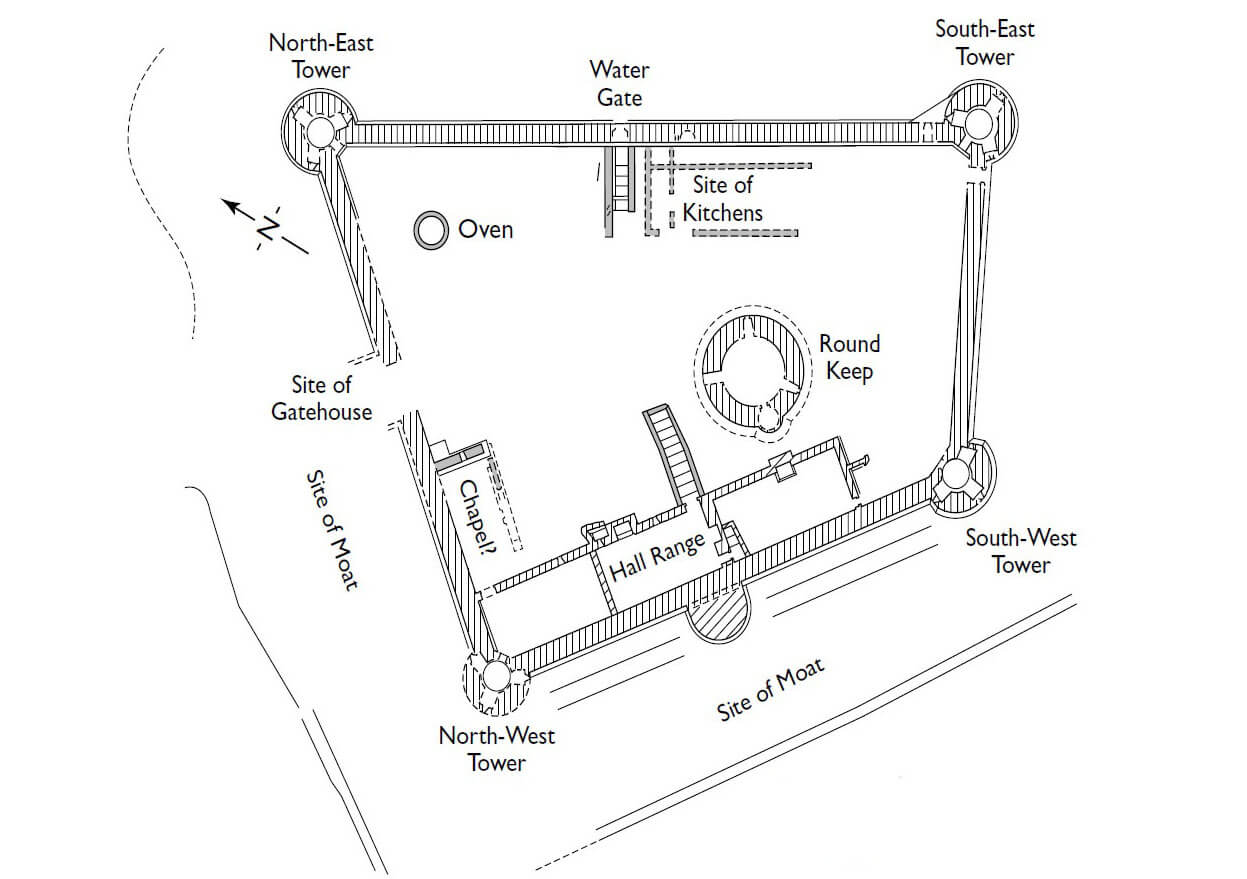

The castle was built on an irregular quadrangle, using red sandstone (Old Red Sandstone), laid in fairly regular layers. The eastern, longest curtain wall was 80 meters long, the northern and western curtain walls were 60 meters each, and the southern curtain wall was only 40 meters long. With the exception of the riverside wall, all were reinforced at ground level with a high batter. At the crown, the walls were topped with a parapet with a battlement protecting the wall-walk and, at least in some sections, with hoardings set in openings spaced approximately 3 meters apart. Originally, the castle was surrounded by a moat, the bed of which was lined with stones and filled with water from the nearby river. The moat was 2.7 meters deep and 14 meters wide. It was separated from the curtains by a narrow strip of land, 2.1 meters wide. The entrance to the castle was located in the center of the northern wall, in a rather simple gatehouse with a portcullis preceded by a drawbridge. On the eastern side, there was an additional postern leading to the nearby river, blocked by a bar set in an opening in the wall.

The castle’s corners were reinforced with rounded towers, half or three-quarters circular, protruding slightly in front of the perimeter of the fortifications, each with an external diameter of approximately 7.5 meters. Towers were two stories high and had cylindrical, unlit cellars beneath them, capable of storing significant quantities of supplies. This solution perhaps reflected Hubert de Burgh’s experience defending Chinon and Dover castles, which were subjected to prolonged sieges. Neither fireplaces nor latrines were located within the towers, leaving them to a purely military function, with three radially arranged embrasures on each of the two stories (one arrowslits facing the foreground and two flanking the adjacent curtains). Entrances to the towers were located at a height of 1.8 to 2.5 meters, requiring ladders or wooden stairs. The cellars had no direct access from the courtyard level; it had to be accessed through openings in the floor of the upper story. Near the south-eastern tower, an opening at a height of 1.5 metres probably led to a latrine, and a similar one on the opposite side of the tower either led to a latrine or was a postern.

The castle’s western curtain, facing the valley mouth on the Welsh side of the border, and thus potentially most vulnerable to attack, was reinforced in the late 13th century with a semicircular tower projecting towards the moat, attached externally to the older defensive wall. It had a similar diameter to the earlier corner towers, but was the only one to be built with a full wall up to the level of the wall-walk, without any interior rooms. The arrowslits were placed in the tower only at the level of the wall-walk and above, on an additional defensive level that was likely behind a crenellated parapet and probably uncovered by a roof. Due to its location just above the moat, the semicircular tower also served as a latrine.

The castle’s buildings consisted of a long residential and utility wing, attached to the western curtain. Originally, the ground floor had a long room in the northern section and a smaller chamber in the southern section. By the end of the 13th century, the northern part was divided into two smaller rooms by a partition wall. The main hall was located on the upper floor, above the room with fireplace on the ground floor. The southern end of the building contained a water cistern. On the opposite side of the western wing was a rectangular, late medieval kitchen building. It was divided into two parallel, narrow sections, each with its own cooking hearth. A large, circular bread oven was also located at the end of the building. The thin perimeter walls of the kitchen indicate that its upper part may have been of timber or half-timbered construction. Near the northern curtain wall, west of the gate, a narrow building may have housed a chapel.

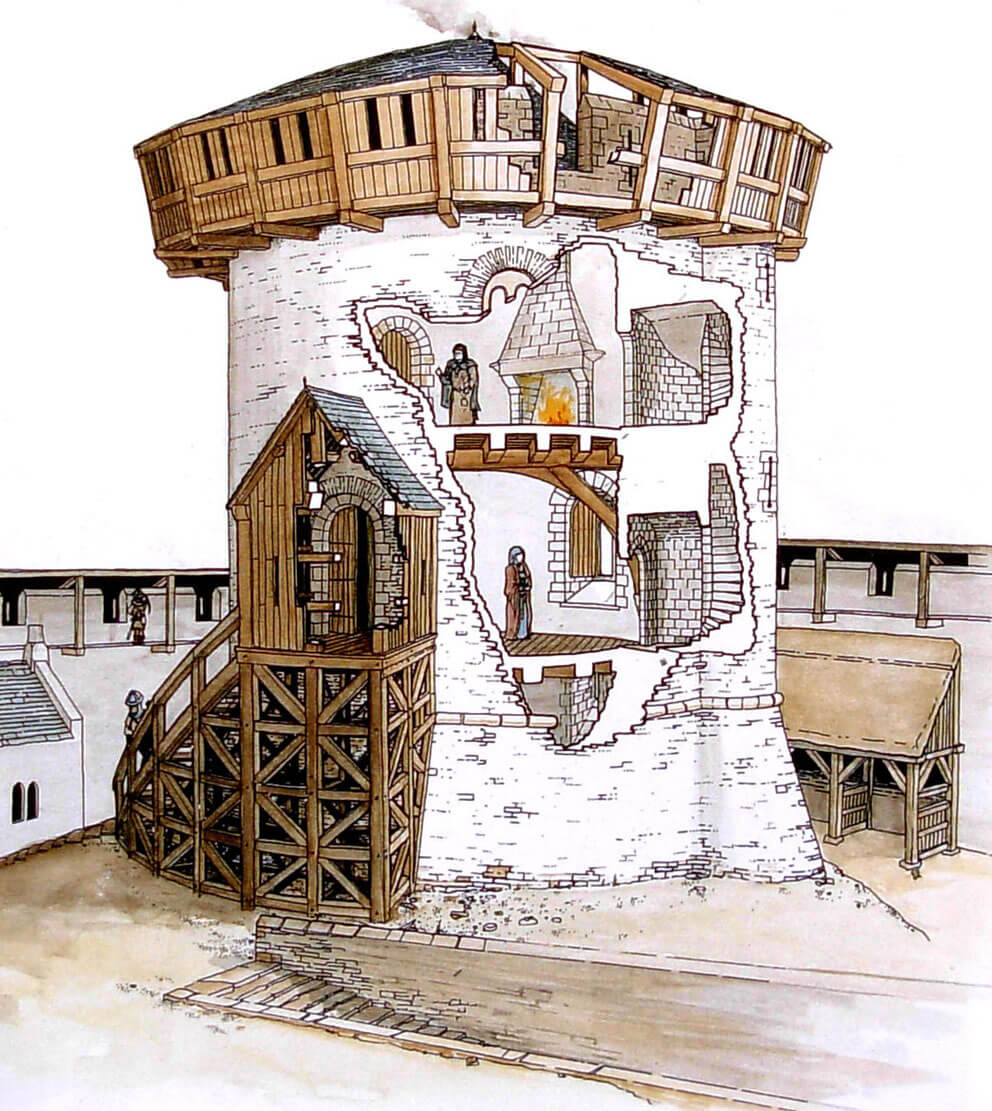

The main building of the castle was a cylindrical keep, built around 1230, located in the southern part of the courtyard. It stood on a slight, 2-meter rise in the ground. Its walls were 2.2 meters thick, with three stories, each measuring 6.4 meters internally (with an external diameter of approximately 11.2 meters). The building’s plan did not form a perfect circle, as a staircase slightly bulged out from its mass on the southwest side. Originally, the keep was topped with timber hoarding porch, its base was widened by a batter and distinguished by a circumferential string. The walls were whitewashed to protect against moisture and rainwater. For defensive purposes, the entrance was created on the second story, accessible by wooden stairs through a semicircular portal and lit by single-light windows. From there, a spiral stone staircase led up to a private living chamber, heated by a fireplace and equipped with a projecting latrine. This upper chamber was lit by two semicircular windows, perhaps originally two-light. Stairs then climbed even higher to the defensive gallery. The utility room, lit only by two narrow openings, was likely accessed by a ladder through a trapdoor in the first-floor floor.

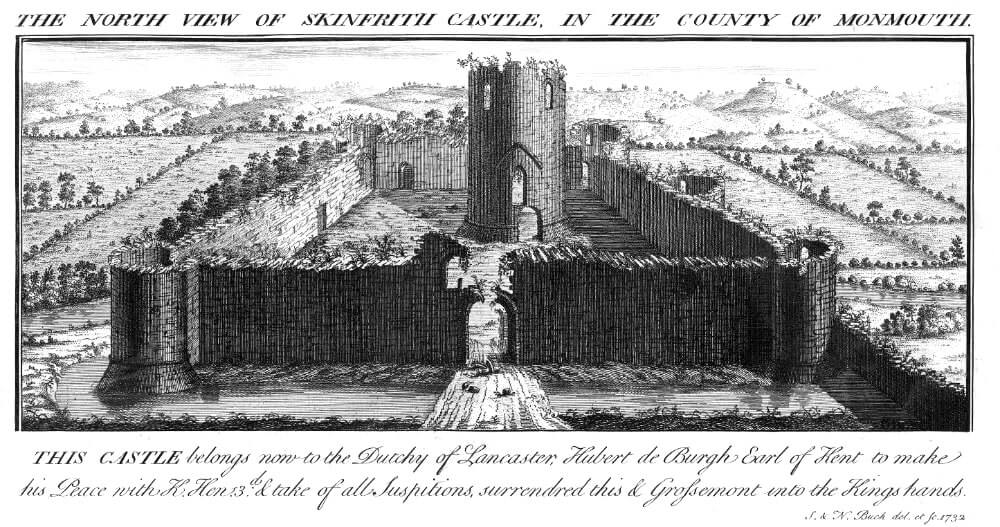

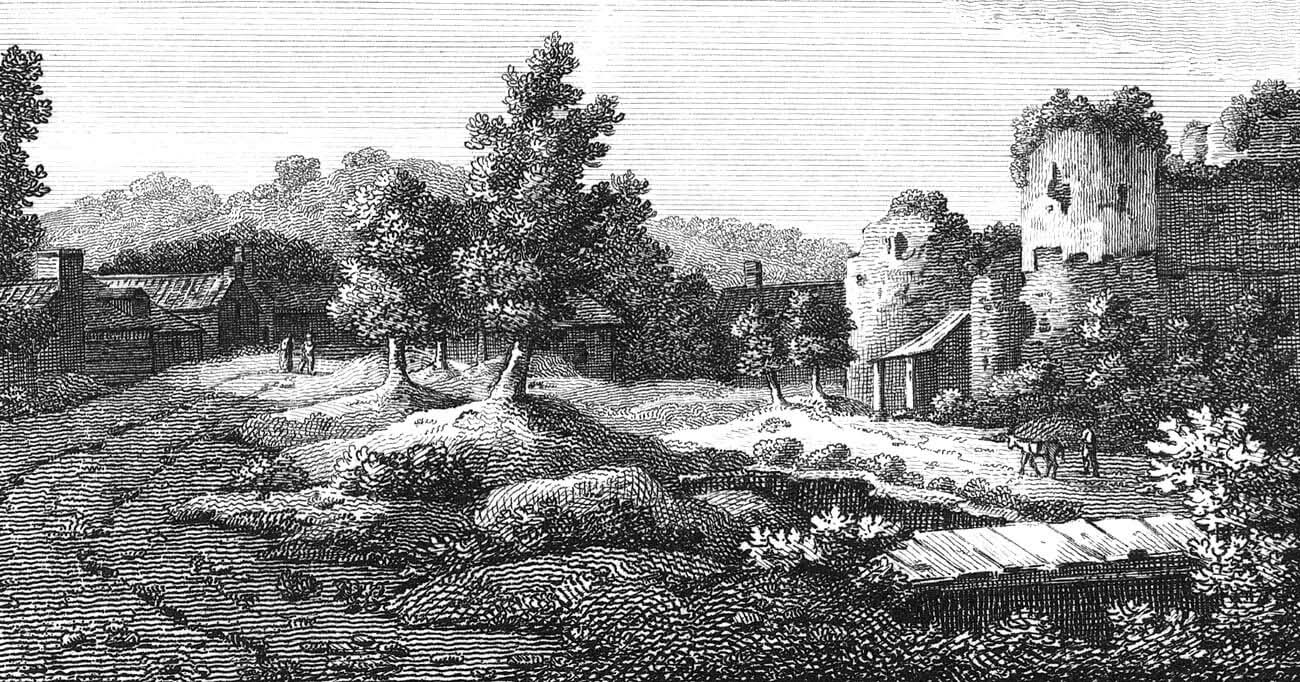

Current state

The castle has been preserved to modern times in the form of a ruin. The defensive walls have survived on almost the entire perimeter and currently reach up to a height of 5 meters. Three of the four corner towers and the west latrine tower are visible. The most valuable element, however, is a well-preserved cylindrical keep. Unfortunately, there is no longer an entrance gatehouse, nor internal development, which is proven only by relics of foundations. The castle ruins are under the care of the Cadw government agency and are made available for sightseeing by it.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Knight J., The Three Castles: Grosmont Castle, Skenfrith Castle, White Castle, Cardiff 2009.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.