History

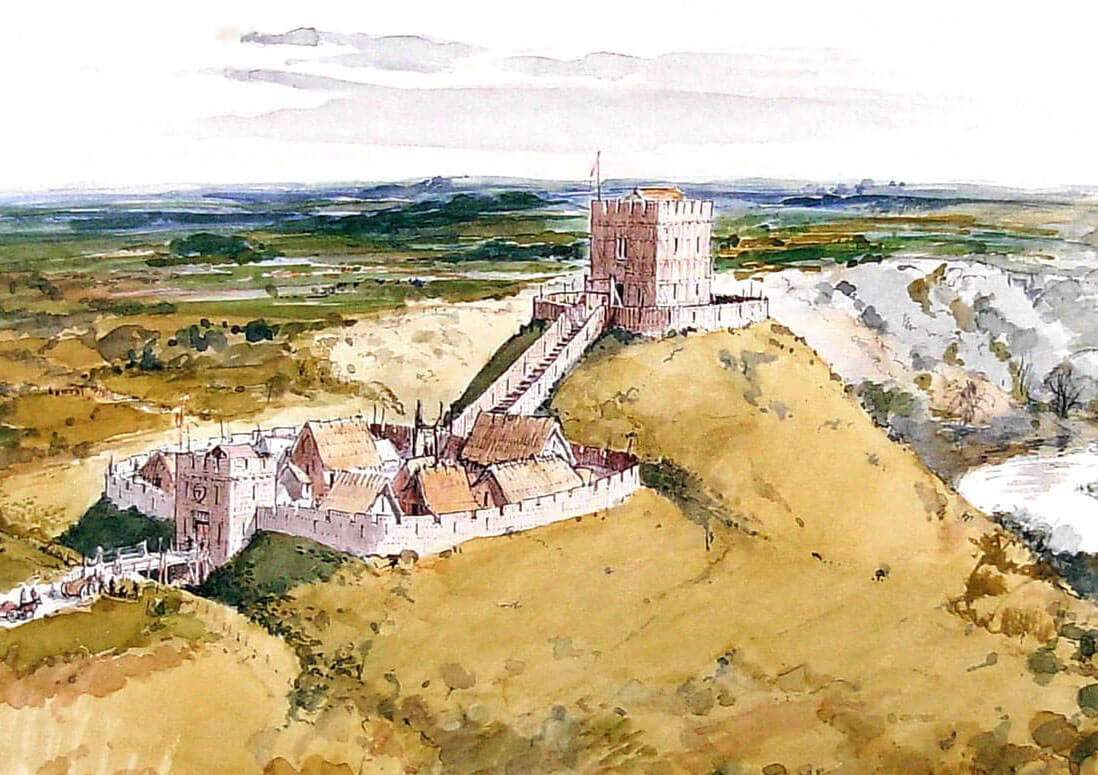

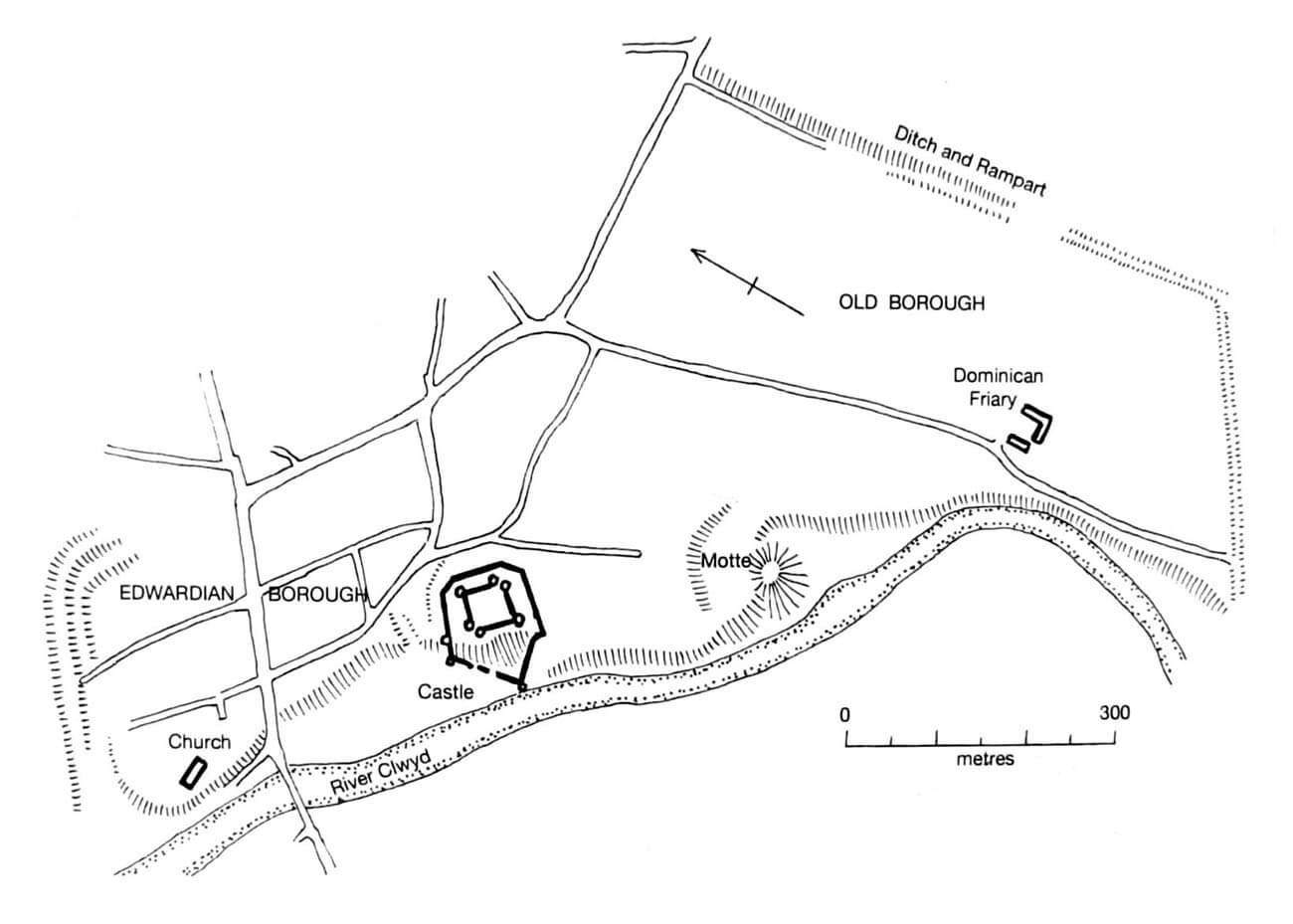

Strategically located near the crossing of the River Clwyd, Rhuddlan had been a battleground since the 11th century between the Welsh rulers of Gwynedd and the Anglo-Norman earls of the border marches. In 1073, at the initiative of Robert of Rhuddlan, they erected a timber motte castle on nearby Twthill Hill. The conflict between the Welsh and the Anglo-Normans, during which Rhuddlan was captured several times, continued throughout the 11th and 12th centuries, ultimately culminating in the war between the Prince of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, and King Edward I of England. Edward invaded north Wales, erected a new stronghold at Flint, and advanced towards Rhuddlan, where in September 1277 he began construction of a stone castle. Along with the town, it was officially granted to the English Crown three months later, following the signing of the Treaty of Aberconwy between Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Edward I.

Work on the castle began under the supervision of Master Bertram of Gascony, but construction was soon handed over to the Savoyard Master, James of St George, the king’s chief architect, who supervised it until its completion in 1282. As early as August 1277, Edward employed 1,800 men to clear a road through the wooded area between Flint and Rhuddlan, and by September, he had employed 968 workers in Rhuddlan for digging trenches. It is known that Edward and Queen Eleanor stayed in Rhuddlan in 1278, likely still living in the old castle or in a temporary camp. The towers of the new structure were to be roofed in 1280, while the great hall was shingled a year later, suggesting that the main construction work had already been completed than.

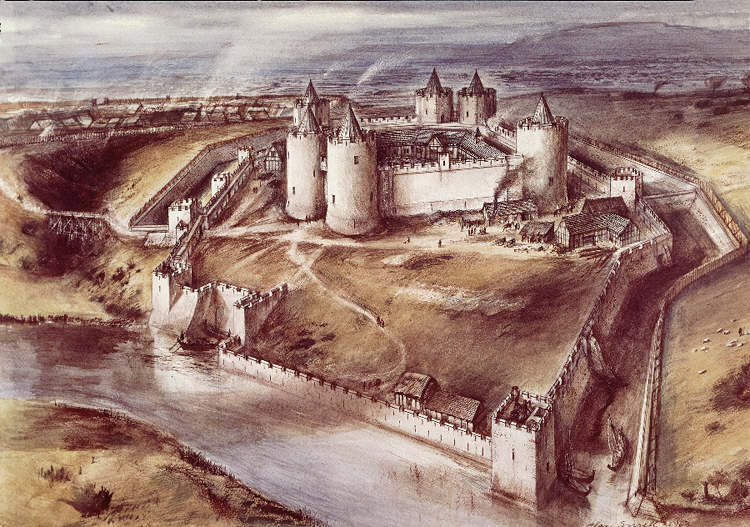

During the Second War of Welsh Independence, which broke out in 1282, the castle may have suffered a series of raids, but it was not captured. After the Welsh retreat, timber was sent to Rhuddlan to complete the ramparts around the damaged town. However, from June 1283, materials intended for Rhuddlan were sent to Caernarfon. The English response to the Welsh revolt was the conquest of all of Gwynedd and a castle-building program with Caernarfon, Conwy, Beaumaris, and Harlech. As a result of the relocation of the border and removal of the threat of attacks, Rhuddlan declined in importance, although after the end of the conflict, efforts were made to improve the castle and town’s defenses by ensuring the possibility of supplying them by sea. For this purpose, the River Clwyd was canalized for over two miles. In addition to the defensive works, timber and shingles were shipped to Rhuddlan in 1283 for the construction of the queen’s goldsmith’s workshop in the castle bailey. Repairs continued in 1285, when the queen’s chapel and additional living quarters were constructed. By 1282, the castle must have been in good enough condition for Elizabeth, Edward I’s eighth daughter, to be born there, and two years later, the Statute of Rhuddlan was signed there (it introduced a new administrative division into counties and English common law to the lands of the former Welsh princes, enforced by royal officials such as sheriffs, constables, and bailiffs).

In 1294, the castle was attacked during Madog ap Llywelyn’s Welsh rebellion, but again it was not captured. The 14th century brought a longer period of peace, as it was not until 1382 that Richard II sent the knight Henry Conewey to Rhuddlan to secure the castle against potential enemies of the king. The castle’s official constable at that time was Alan Cheyne, who had held the post since 1366, but rarely visited Rhuddlan in person. In 1384, Henry Conewey was once again sent to reinforce the castle, achieving the rank of constable within a year. He was still in office when in 1399 King Richard II stopped in Rhuddlan on his way to Flint, where he was captured by his rival, Henry Bolingbroke, and subsequently forced to abdicate. Shortly before, Henry Conewey had been forced to surrender the castle to anti-royal opposition and the earl of Northumberland’s army, after securing a lifelong constableship at Rhuddlan.

During the internal conflict, the troops looted all the weapons stored at Rhuddlan Castle. These were likely replenished quite quickly, as when Owain Glyndŵr’s rebel forces approached the castle in 1400, the fighting was more of an armed demonstration, without a decisive assault on the sufficiently equipped structure. A more serious raid occurred in 1403, when the town was burned and the townspeople’s possessions plundered. Over the following weeks, unsuccessful attacks on the castle were resumed periodically. During these attacks, the garrison reportedly used up 33 sheaves of arrows from a reserve of 41 and broke 13 of its 27 bows. A total of around 900 arrows and bolts were fired, leaving only 200 in the armory. Only the rebels’ retreat across the River Conwy in October of that year temporarily relieved the pressure on the castle’s defenders. It was again threatened during the height of the uprising in 1404-1405. Supplies were then maintained by sea from Chester, where bows and arrowheads were primarily purchased, despite financial difficulties. When the Welsh rebellion subsided in 1406, the number of archers maintained at the castle was reduced from 19 to 12.

At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the castle’s condition deteriorated, reflecting its diminished strategic and administrative importance. It was garrisoned again during the English Civil War in the 17th century. At the time, Rhuddlan was held by royalist forces loyal to King Charles I. After the Battle of Naseby, victorious Parliamentarian forces under Thomas Mytton besieged the castle in 1646. Two years later, on Oliver Cromwell’s order, it was partially demolished to prevent further military use. In 1944, the then-owner of the castle ruins, Admiral Rowley-Conwy, transferred custody of the monument and Twthill Hill to the then Ministry of Public Works. As a result, systematic work began in 1947 to conserve and protect the medieval buildings.

Architecture

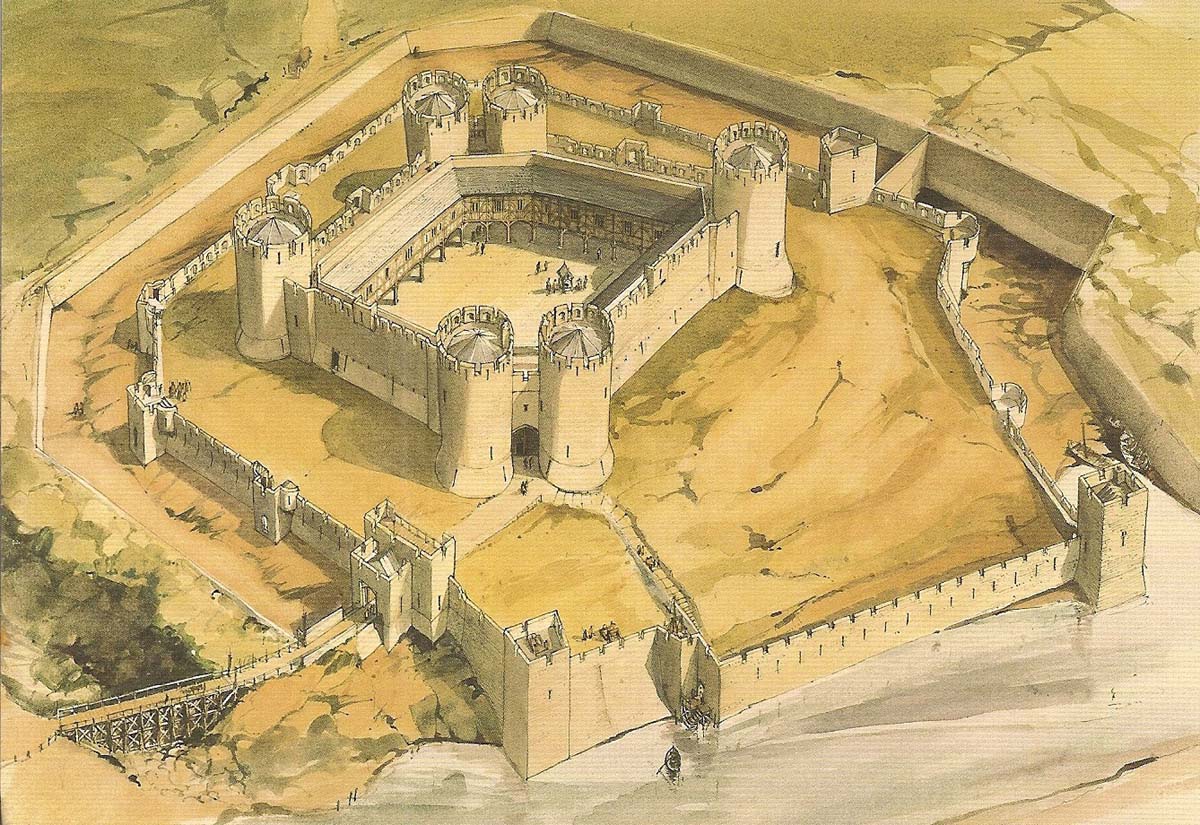

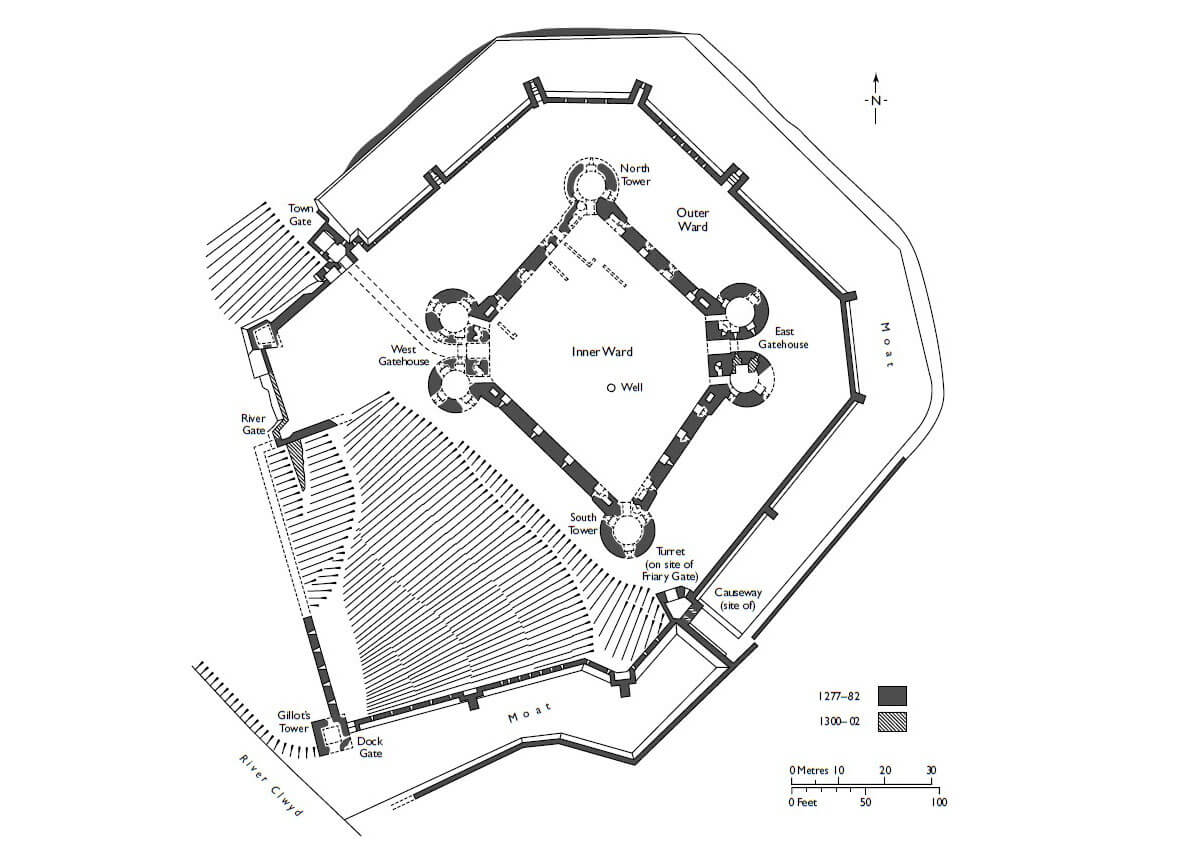

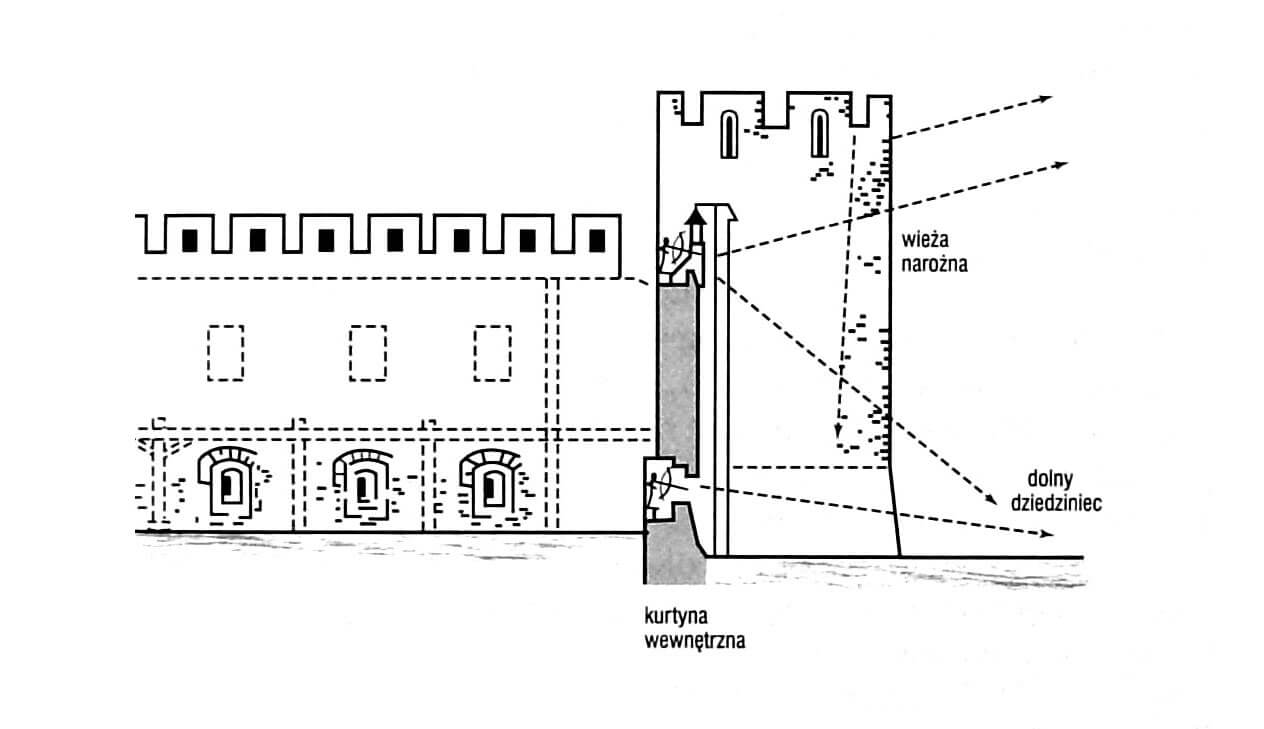

Rhuddlan Castle was situated on the eastern bank of the River Clwyd, on the northern side of the older motte of Twthill and on the southeastern side of the newly founded town with its parish church. The castle was built as a concentric, symmetrical structure, with a diamond-shaped main circuit of walls surrounding a courtyard measuring approximately 45 x 40 meters. Its defenses included four straight curtains, two cylindrical corner towers approximately 11 meters in diameter, one each on the north and south sides, and two gatehouses at the eastern and western corners. A circumference of the outer defensive wall, reinforced with numerous small half towers and two towers, ran a dozen or so meters away, and the outer defense zone was a wide moat, except for the southwestern section, where the river took over its role.

The single northern and southern corner towers protruded almost entirely from the curtain walls, allowing to flank adjacent sections of the fortifications. Northern and southern towers had a similar layout with four main stories and were reinforced with battlements and a batter, like the adjacent curtains. The southern tower also had a basement below ground level, accessible through an opening in the ground floor. The basement and ground floor were cylindrical, the first and second floors were hexagonal, and the top floor again circular. This may indicate that the first and second floors were used for residential purposes, for which a form with straight walls was more convenient. In the northern tower, the ground floor room was located partly above and partly below the courtyard level. Lacking natural light, it was essentially a basement, but access was via stairs leading down directly from the courtyard, rather than through a trapdoor in the floor, as was the case with the basement in the southern tower.

The east and west gates were almost directly opposite each other, because offset from the axis was about 1.2 meters. Each consisted of two massive, cylindrical towers, protruding from the face of the walls and flanking the passage between them. It were approximately 18 meters high, thus towering some 5-6 meters above the adjacent curtains. Their rear sections had straight walls, like those of the northern and southern corner towers. Each gate tower contained a circular room on the ground floor with three radially arranged arrowslits facing the foreground (and a single one facing the interior of the gate passage). Above them were three stories, each with hexagonal chambers separated by wooden ceilings. The penultimate floor was lower, less lit, and unheated. Unlike the other residential floors, it may have served as ammunition depots. This was also the level where the towers were connected by short flights of stairs to a wall-walk. Above was a floor containing rooms heated by fireplaces and an open defensive gallery surrounding the conical roofs. Vertical communication was provided by spiral staircases embedded in the thick walls, accessible from the entrance corridor leading from the courtyard (or rather from the buildings situated along the courtyard walls) and terminating on the third floor. The galleries around the tower roofs were accessible by separate, shorter staircases from the top floors.

The gate passages were protected by portcullises and double-leafed doors locked with a bar. It were 9.1 meters long and 2.7 meters wide, narrowing to 2.1 meters behind the portcullis. Both the approach and the front of the gateway itself were protected by two embrasures in each of the flanking towers, which housed the aforementioned circular guardrooms or gatekeepers’ quarters on the ground floor. In the eastern gatehouse, in the southern chamber, two embrasures were bricked up to allow for the construction of a large fireplace in front of them, while the wall between them was chiseled away to create a flue. These changes were made in 1303, when payment for the construction of a fireplace in the gatekeeper’s chamber was recorded, to prevent fire hazards. Access to the guardrooms, as well as to the gatehouse staircases, was via narrow passages parallel to the main gateway.

The castle walls were considerable, approximately 2.7 meters thick. It reached a height of 10.7 meters to the level of the wall-walk. At the base, the curtains were framed externally by a sloped plinth called a batter. It were topped by a battlemented parapet, the merlons of which were pierced with arrowslits. Each curtain wall had a central machicolation box, supported by corbels at parapet level. Their purpose was to provide additional protection against attacks at the most vulnerable points, i.e., midway between the towers. On the sides of the curtains adjacent to the towers, thickenings up to 3.3 meters wide housed latrines. At ground level, the walls were pierced with arrowslits set in deep recesses with segmental heads. There were four arrowslits on each side, except for the northern section, which had replaced one arrowslit with a postern. It was likely intended to allow supplies to be delivered without the need to raise a portcullis or open the large doors at any of the main gates.

The inner courtyard was occupied by timber-framed buildings, which adjoined the inner faces of the defensive walls. Among them were a hall, a chapel, a kitchen and royal apartments. A 15-meter-deep well stood in the center of the courtyard. The buildings were attached to the castle walls with beam sockets, and their shingled roofs left imprints on the facades. The buildings on the northeast and northwest sides were larger, and it is possible that the two chambers of the king and queen were located there, flanking the central kitchen near the northern corner. This arrangement would have ensured that all the private living quarters received southern sunlight. The main rooms were located on the first floor, supported by wooden pillars that likely formed open arcades below.

The outer bailey was surrounded by the outer ring of defensive walls, extended towards the bank of the Clwyd River and surrounding the entire upper ward. It was strengthened by 9 half-towers opened from the inside and two closed towers located on the river, on the west side. The larger of them on the south-west side, called the Gillot’s Tower, was erected on a square plan with sides about 7.5 meters long. It had four floors, the third of which was connected with the adjacent curtains of the walls. The chamber on the top floor was heated by a fireplace and illuminated by unusual small four-sided holes pierced just above the arrowslits. Small half towers were not roofed, they probably did not exceed the curtains of the outer wall. Interestingly, some of them had stairs and doors leading to the bottom of the dry moat.

The characteristic shape of the outer bailey meant that on three sides of the main part of the castle it provided only a 20-meter-wide zwinger, while a wider, about 60-meter-long space to the river was on the slope. Probably there were wooden stables, granaries and various types of workshops, known from written sources. The entrance was provided by two gates: Town Gate on the north side and Friary Gate on the south side. The latter had the form of a small, irregular tower with a passage in the ground floor, behind which the causeway led across the moat. The Town Gate, on the other hand, was a wide gatehouse, open from the side of the outer ward, preceded by a small foregate. An additional water gate was on the west side and probably led to a wooden coastal pier. The outer zone of defense was provided by the already mentioned wide dry moat. Its western part reached the river and formed a dock for supply boats.

Current state

The castle has survived to this day as a ruin. Most of the main defensive walls remain, along with the almost completely preserved western gate and southern corner tower. Unfortunately, the northern tower and eastern gate are severely damaged. Much of the curtain walls have survived to the level of the battlemented parapet, a single fragment of which is visible where the northeastern curtain meets the northern tower. Little remains of the outer fortifications, of which the best-preserved element is the southern tower, originally defending the dock (Gillot Tower). The castle moat can also be admired in its full glory. The castle is open to visitors from March 24th to November 4th, from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

bibliography:

Berridge P., Blockley M., Quinnell H., Excavations at Rhuddlan, Clwyd: 1969-73, Mesolithic to Medieval, York 1994.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Messham J.E., Henry Conewey, Knight, Constable of the Castle of Rhuddlan 1390-1407, “Flintshire Historical Society Journal”, Vol. 35/1999.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Taylor A. J., Rhuddlan Castle, London 1975.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, II County of Flint, London 1912.