History

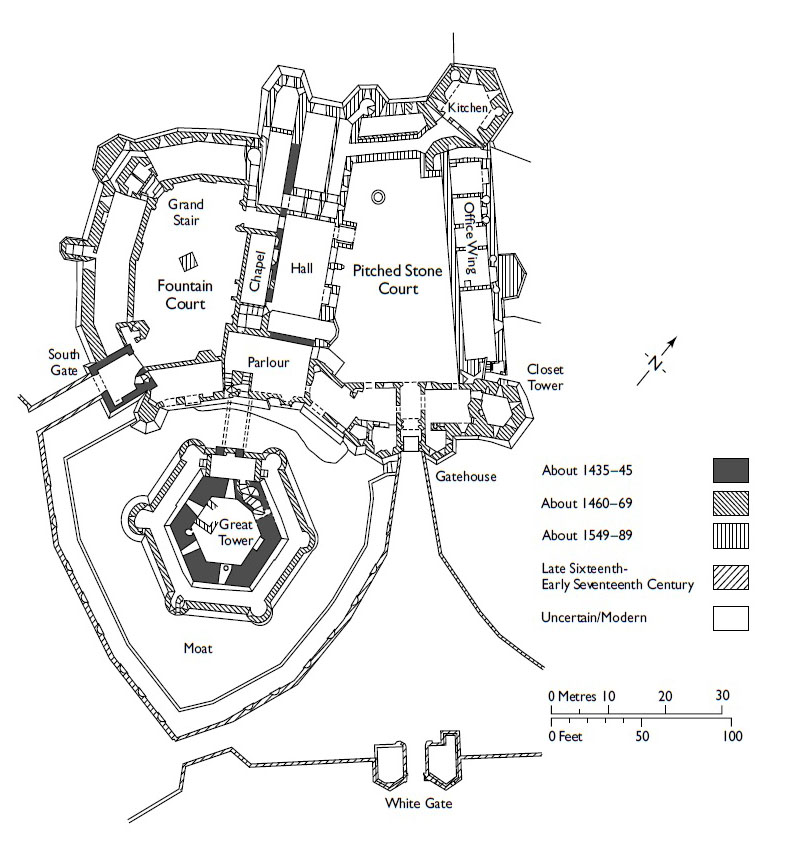

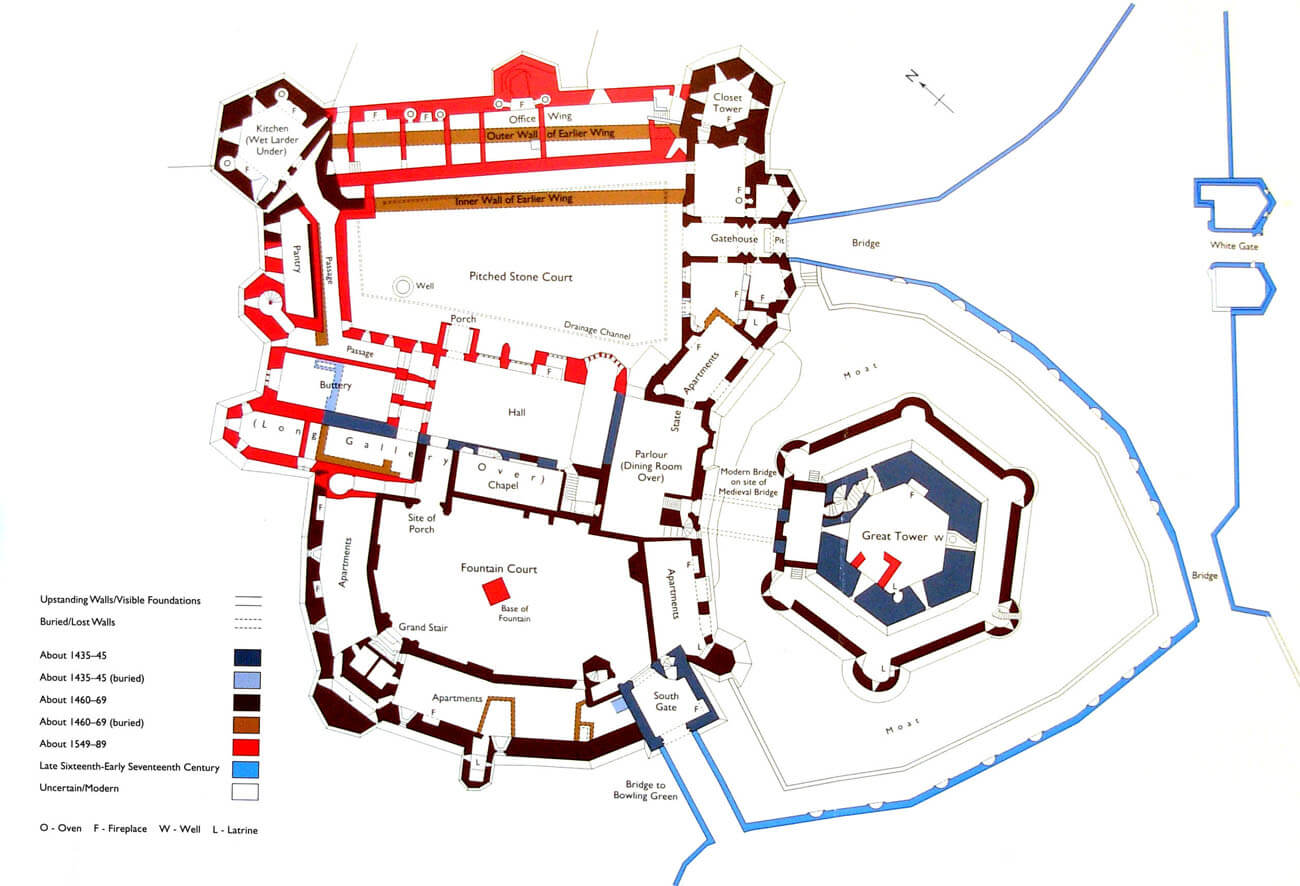

In the 11th century, the area around the village of Raglan was given to the Norman lord William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford. Perhaps he built a small, timber-and-earth motte and bailey structure, as the location of Raglan near the old road from Chepstow to Abergavenny, at the crossing with the road from Gloucester to Usk and Caerleon was of strategic importance. From 1172 to the end of the fourteenth century, the nearby lands belonged to the Bloet family, who built a manor house in Raglan, consisting of residential and economic buildings and a chapel, grouped around at least one courtyard. In the second half of the fourteenth century, with the death of Sir John Bloet, the manor became the property of his daughter Elizabeth, who first married Sir James Berkeley, and after his death again in 1406 she married William ap Thomas, the younger son of a minor Welsh family, who was promoted in the political hierarchy in the first half of the 15th century. In 1421 he was a steward of the lordship in Abergavenny, five years later he was knighted by Henry VI, and in the years 1442-1443 he became the main steward of the estates of Duke of York in Wales. In 1432, William bought the Raglan manor from the Berkeley family and began construction works on the new castle. He died in 1445, apparently mourned at a funeral by as many as three thousand mourners.

William’s son resigned from the Welsh version of his name, calling himself William Herbert, in memory of the fictitious, illegitimate son of King Henry I. The importance of his and the family grew during the War of Roses as supporters of the Yorks and during the Hundred Years War in France, where in 1450 Herbert got captured after the battle at Formigny. After paying the ransom and freeing, he was knighted two years later and then focused on consolidating his estates and developing trade links with France. He made a fortune in the wine trade brought from Gascony to the port of Bristol, and the fame gained at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross in 1461, in which he played a leading role in defeating Lancaster forces. After Edward IV ascended the throne, he became his trusted chamberlain of South Wales, and then Baron of Raglan. He was also the first Welshman to receive the title of Earl as a reward for the capture of Harlech Castle, the last Lancaster fortress in England and Wales. In the 60s of the 15th century William used his growing wealth to rebuild the castle on a much larger scale and symbolically show his wealth, influence and greatness of the family in architecture.

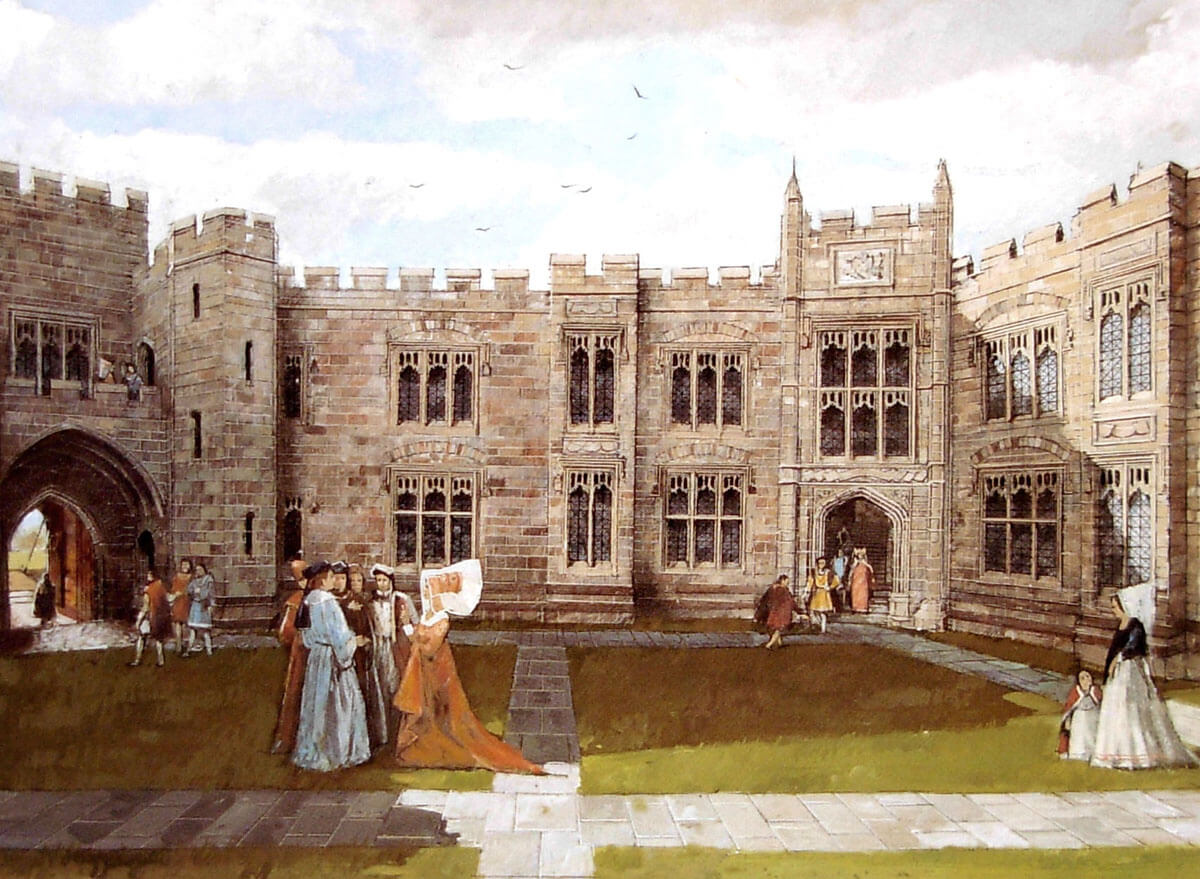

William Herbert, as a supporter of the York family, was executed in 1469 after the Battle of Edgecote Moor. The construction works were stopped at that time, and William’s son, also known as William Herbert, only carried out minor works and repairs in the late 1470s due to financial problems. In 1491, after the death of William II, the castle passed to Elizabeth Somerset, daughter of William Herbert, who a year later married Sir Charles Somerset, passing Raglan Castle to a new line of the family. Their son Henry, the second Earl of Worcester, and grandson William continued the expansion of the castle in the 16th century, eventually transforming it into a Renaissance residence. These works were carried out, among others, by importing lead from the dissoluted medieval Tintern Abbey in 1546. Further early modern transformations, mainly related to the terraces and gardens around the castle, were introduced at the beginning of the 17th century, in the time of Edward, the fourth Earl of Worcester.

In the forties of the 17th century, during the English Civil War, the castle was owned by Henry, fifth Earl of Worcester, who was a staunch royalist. Despite the defeat of the royal army at the Battle of Naseby in 1645, he remained loyal to the king and placed in Reglan, at his own expense, a garrison of up to 800 soldiers. In addition, the castle was reinforced with earth bastions, trees were removed outside the gates of the castle, and neighboring buildings were destroyed to avoid their use by enemies. The army of Parliament arrived in June 1646, and as Henry refused to surrender, the castle was surrounded and the siege began. The garrison of the castle lasted until August 16, 1646, when Reglan was surrendered. The winners decided to destroy the castle to prevent its military re-use.

Architecture

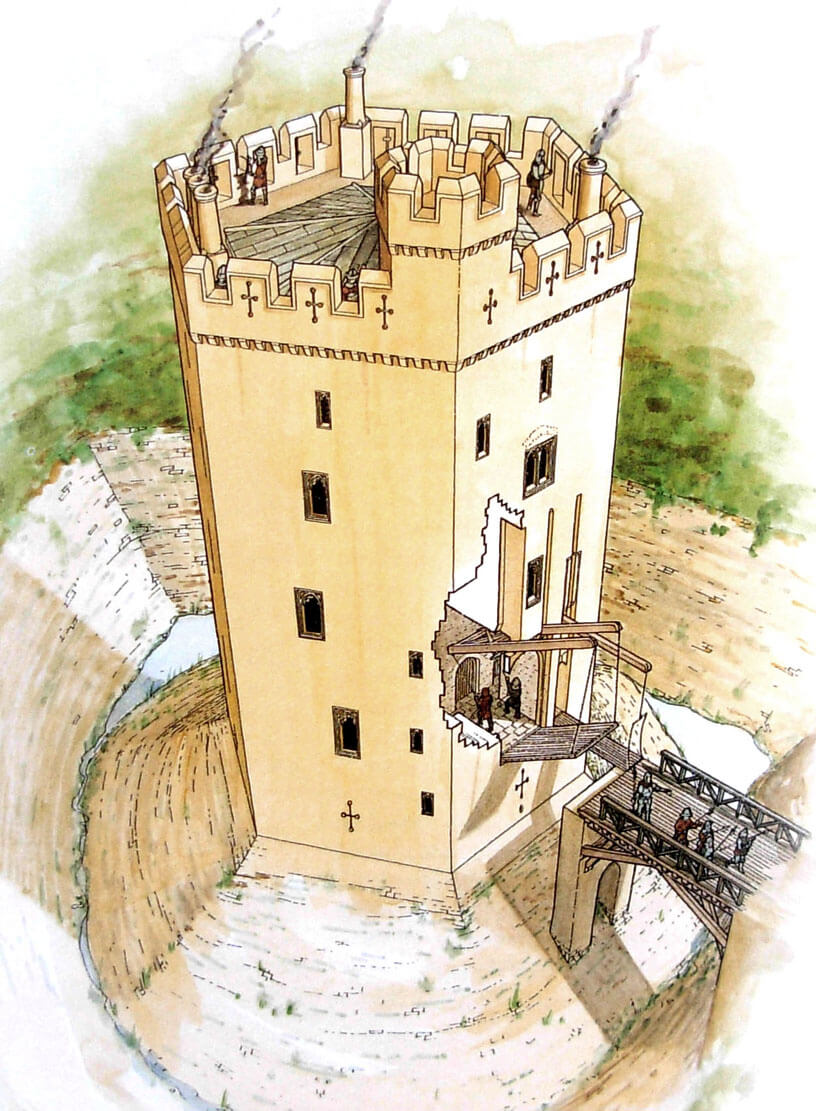

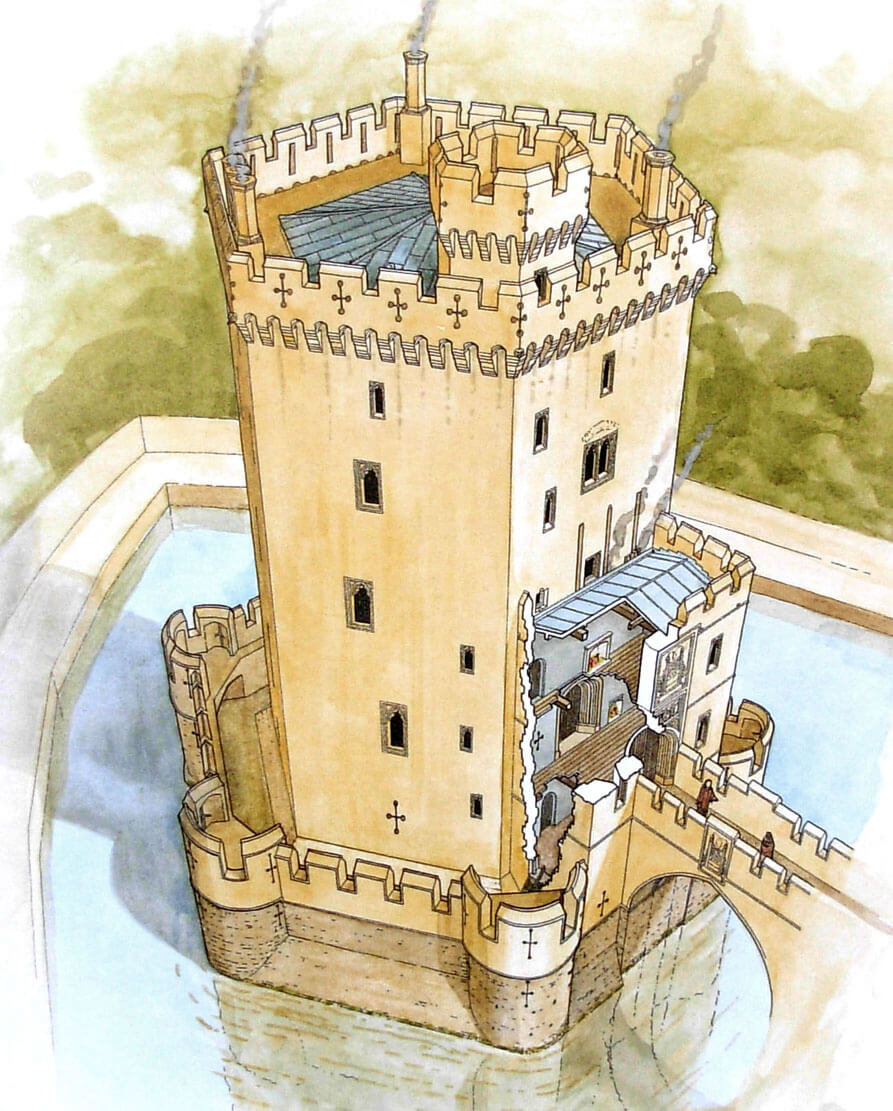

The Raglan Castle was built of light sandstone from Redbrook, later also Old Red Sandstone and limestone from Bath for architectural finishes and details were used. The oldest and main element of the fifteenth century castle was the late-medieval keep, a huge tower built on a hexagon plan with a diameter of 17 meters and walls up to 3.2 meters thick, symbolically and physically dominating over the rest of the buildings. It was erected quite atypically outside the perimeter of the defensive walls and surrounded by an irrigated moat, while access to it was only possible through the rest of the castle. It was an independent defense work, capable of withstanding a long siege thanks to the kitchen and latrines, and also served as a residential building during peace. It had five floors separated by wooden ceilings with a single room on each floor. It was crowned with a battlement on the machicolations and a smaller observation turret. The entrance to the tower led through a timber bridge supported on two stone pillars, which just before the tower had two side-by-side drawbridges: a smaller footbridge carried by one arm, functioned for everyday pedestrian use, and a larger bridge lifted by two arms, used during more important events and for horse riders. In the 1460s, the timber bridge was replaced with a stone one, and a stone forebuilding was erected in place of the drawbridges. Accessible from it stairs, placed in the thickness of the tower’s wall, led to the kitchen located in the ground floor, as well as to the embrasures and private chambers above. From around 1460, the tower was surrounded by a low outer wall, equipped with six small corner towers, open from the inside. One of them had a latrine, and the other had a postern gate opening to the moat that surrounded the tower.

The lowest storey of the keep was equipped with both a fireplace embedded in one of the walls and a well, so it was probably used as a kitchen, despite its illumination only through cross-shaped arrowslits with circular ends of the arms. The dark room was also illuminated by circular loop holes intended for handheld firearms. The well was located in one of the niches of the loop hole, with the water draw mechanism probably rendering it useless from a military point of view. A small portal also led to the latrine in the kitchen. In addition, later in the kitchen, an even smaller room was separated by a wall, perhaps used for storing more valuable tableware and cutlery. The room above the kitchen was a living room equipped with a fireplace and single-light windows, as well as a single cross arrowslit. The comfort of the chambers increased with the spiral staircase going up, each higher room had slightly larger windows, some already two-light and provided with side seats and more decorative fireplaces. There were also latrines in all of them.

From the second half of the 15th century, the main entrance to the castle led over the moat, through the drawbridge, through the Great Gate on the eastern side. It consisted of twin, pentagonal towers flanking the passage between them. When raised, the bridge hid in a four-sided niche (its rear part was lowered into the pit in the gate passage), and the passage was originally vaulted and additionally protected by three double-leaf doors and two portcullises. On the sides in the towers there were rooms for guards from which two side openings were directed at the passage between the portcullises. Both the gate and towers were crowned with machicolations and battlements, as well as gargoyles, which, in addition to decorations, drained rainwater. Protection was also provided by numerous round holes at ground level, although many of them were pierced inside latrines and fireplaces, so they had more symbolic significance. The real defense of the gatehouse was also lowered by large windows, numerous in the outer façades of the towers. The upper two floors of the gate were occupied by the chambers of the constable of the Raglan Castle, connected to the latrine in the corner at the south-west tower. Its chute was just above the water level in the moat. Portals in the back of the gateway led to large side chambers with windows facing the inner courtyard. Communication between them and the first floor was ensured by a spiral staircase located in the wall thickness, and a horizontal communication by gallery above the passage on the first floor. The façade of the gallery from the courtyard side was opened in the 16th century with new windows with high-quality decorations. Directly west of the gate was the castle library, once known for its large collection of Welsh literature.

Behind the Great Gate was a spacious Pitched Stone Court surrounded by kitchens, breweries and other utility rooms, as well as the building of the great hall on the west side, which divided the Raglan Castle into two parts, both physically and in the form of a rank. There was a well in the northwestern part of the courtyard.

The north-east wing was significantly expanded during the Renaissance rebuilding of the 16th century. Originally, it was situated deeper in the courtyard, so that the corner towers were extended beyond its outer walls. In the southern part it housed a 15th-century latrine, moreover there were probably a bakery, brewery, and maybe stables in it. The west wing with a great hall and pantry was originally two-storey and slightly shorter, it did not protrude from the north outside the buildings and the perimeter walls. In its length there was also a passage to the second castle courtyard. The hall before the early modern reconstruction was 13 meters high, had an open roof truss made of Irish oak and was equipped since the 16th century with carved wooden panels and a gallery for minstrels. It was used more for the most important ceremonies and parties than for everyday meals.

The eastern corner of the courtyard was protected by a huge, six-sided Closet Tower, and the northern corner by an even larger, also six-sided, Kitchen Tower. In the 16th century, another pentagonal tower was added between them. Built in the second half of the 15th century, the Kitchen Tower, apart from its defensive function, housed rooms for servants on the first floor, a kitchen and a room for preparing meals on the ground floor and a vaulted, cool pantry in the basement. The entrance to the kitchen was preceded by a triangular vestibule, originally illuminated by two narrow windows. The kitchen itself inside housed two large fireplaces, each with an adjacent oven and drain for waste. It had a stone vault, above which the upper floor was divided into two rooms. Of these, the closer one to the outside of the tower was equipped with a decorative fireplace placed between a pair of windows with seats in niches. This chamber probably served a more important person, perhaps a kitchen chief. The second chamber, closer to the courtyard, also had a fireplace, and was illuminated by one three-light and one single-light window. In one of the corners, a narrow staircase led in the thickness of the wall to the upper defensive gallery, equipped with a breastwork with battlement and machicolation. Buildings to the west of the tower were significantly rebuilt in the 16th century, except for one window with a trefoil top and a fireplace.

The Closet Tower was accessible from the courtyard level through two portals in the thickness of its wall. Left led to the polygonal and irregular room in the ground floor, while the right led by the stairs to the basement, which perhaps served as a prison. Its only lighting and ventilation was a long and narrow shaft falling from a slender window. The upper chamber of the ground floor was heated by a fireplace and equipped with a latrine and round loop holes below single-light windows. The upper floors of the tower were accessible only from the chamber at the back of the Great Gate and from the defensive gallery between the tower and the gatehouse (this room could serve as a treasury). It is noteworthy that each floor of the tower was independent of the others, with separate entrances and without vertical connection. The crowning of the Closet Tower was, like the Great Gate, prominent machicolation from which gargoyles protruded in the corners.

Through the corridor located in the building of the great hall and through the porch, you could get to the courtyard on the west side of the castle (Fountain Court). It owed his name to the fountain that was once in its center. It was surrounded by late-medieval buildings erected in the second half of the 15th century, serving mainly residential purposes, with the main entrance through a grand staircase in the western corner. The residential wing was a two-story building and was adjacent to the inner faces of the defensive walls from the west, south and north. Each of its chambers was equipped with a fireplace, a large window with side stone benches and access to latrines located in the towers. The windows facing the outside were single-light, while those from the courtyard side were larger (two and multi-light), more sophisticated and decorative. The layout of the rooms in the ground floor was similar to that on the first floor, but those located closer to the grand staircase were probably occupied by the servants, and further by the family of the castle’s lord and more important people. On the southern side of the courtyard, a turret with a staircase provided communication between floors in this part of the wing. It also had an open gallery at the back of the gatehouse, connecting to the south wing. In the south-eastern corner, the buildings had two floors above the vaulted basement. There was probably one large chamber in the ground floor, and two slightly smaller upstairs. To the east of them, as a link between two courtyards, there were further rooms, later serving, among others, as a dining room, with windows facing both the courtyard and the moat and the keep. They were rooms more private than a great hall, in which larger ceremonies, feasts and parties were organized. The eastern part of the courtyard was occupied by a chapel, over which in the 16th century a long, 38-meter gallery was added. It was paneled, lined with tapestries and paintings, aimed at enabling family and guests to relax. The chapel was probably accessible through the porch forming an extension of the passage between the courtyards. Its interior was crowned with a stone vault mounted on corbels, masterfully carved in the form of human heads, and the floor with decorative tiles in brown and yellow colors.

A modest defense of the Fountain Courtyard was provided by three towers protruding beyond the perimeter of the walls, two on the west side and one on the south side, next to the gate. Their role was more limited to the latrines they housed, than to actually raise the defense of the castle. The entrance was in a four-sided gatehouse called the Southern Gate, which dates back to the first half of the 15th century and was originally the main entrance to the castle. Its short gateway was closed with two double-leaf doors, a portcullis and a drawbridge, and was crowned with an elegant fan vault (perhaps similar to that one used in the Gloucester Cathedral). In the corner of the ground floor there was also a staircase and a fireplace, probably originally separated from the gate passage by a partition screen. Visitors to the castle had to circle the Great Tower and the moat before being able to go through the South Gate, through the courtyard and then enter the keep. After the construction of the Great Gate in the second half of the 15th century, the southern gatehouse became an auxiliary, more private entrance, or was even blocked.

The late medieval castle at Raglan had little features in common with other Welsh fortresses. A large keep located outside the outer bailey fortifications, two parallel drawbridges, prominent machicolations and a high standard of stone carved decorations suggest continental influences. The fact that both William ap Thomas and his son fought in France, may serve as a clue as to the source of inspiration for the construction of the castle.

Current state

The castle, which is currently the best example of a late medieval castle and Renaissance residence in Wales, has survived to modern times in the form of a ruin. Over the centuries, the north-east range of the sixteenth century and the housing development surrounding the Fountain Court suffered the greatest losses. Unfortunately, one of the oldest elements of the castle, the Great Tower, lost the eastern wall and the highest storey. The towers of the Great Gate and the Closet Tower, still having defensive machicolations and decorative gargoyles, have been preserved in good condition. The powerful Kitchen Tower, though without internal divisions and the towers surrounding the Fountain Court, also have survived.

The castle is open to the public and open from March 1 to June 30, daily from 9.30 to 17.00, from July 1 to August 31 daily from 9.30 to 18.00, from September 1 to October 31, every day from 9.30 to 17.00 and from 1 November to February 28 from Monday to Saturday 10.00 – 16.00 and on Sundays between 11.00 and 16.00.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., Raglan Castle, Cardiff 2003.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Morgane G., Castles in Wales, Talybont 2008.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.