History

In 1107, Norman lord Henry de Beaumont, Earl of Warwick, received from king Henry I, the authority on the Gower Peninsula. During this period, Wales consisted of independent principalities and kingdoms, often waging war with each other. Since there was no centrally coordinated Norman invasion of Wales, lords such as Henry de Beaumont were encouraged to conquer border land on their own. This strategy required a large number of castles to suppress resistance and strengthen governments in the newly conquered territories. One of the at least seven, that was then built on the peninsula, was the castle of Henry de Beaumont in Pennard.

In 1203 Gower was granted by King John to the de Braoses, a prominent family of Anglo-Norman nobility from Briouze, Normandy. Members of this family played a significant role in the Norman conquest of England and the subsequent power struggles in England, Wales and Ireland. One of its members, William de Braose, transformed the castle into a stone structure at the end of the 13th century. Perhaps this was due to the dispute that William then led with John de Monmouth, Bishop of Llandaff, and the desire to strengthen his position.

In 1317 William de Braose granted his huntsmen William the rights to his Pennard warren, but the first direct mention of the castle in written sources appeared only in 1322. That same year, Hugh Despenser, Lord of Glamorgan, Edward II’s favorite, was granted a royal license permitting him to obtain by exchange the castles and manors of Swansea, Oystermouth, Pennard, Loughor and Liman (probably Talybont). King Edward II also accused William of granting the castle to his son-in-law, John de Mowbray, without royal permission. Despenser was to be appointed the royal custodian of the castle, but after the fall of Edward II, the influence of the Despenser family also ceased. Pennard was restored to its rightful owners, although in the mid-fourteenth century there were legal disputes between Earl of Warwick, Thomas Beauchamp and John de Mowbray.

From the end of the fourteenth century, the castle began to feel the strength of the sand blown from the coastal dunes. It eroded castle walls, made agriculture impossible and made life difficult. This resulted in the transfer of the nearby church in the 15th century, and finally the abandonment of the castle and the nearby settlement in the first half of the 16th century. In 1650, an inventory of the court noted that the castle was abandoned and ruined, and not renovated for so long that there is hardly any wall there, and the rest is covered with a lot of sand.

Architecture

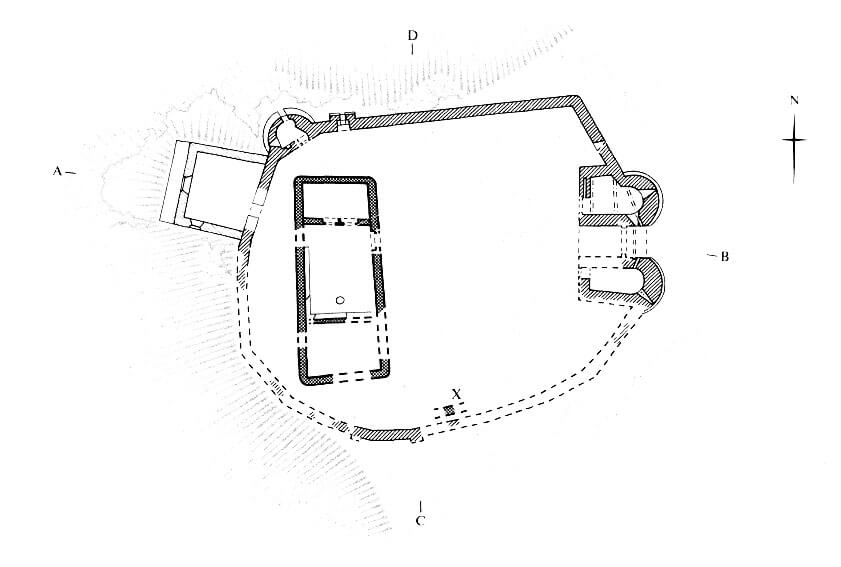

The castle was well protected by the natural conditions of the area. On the west and partially north sides, the defenses were reinforced by high cliffs, descending towards the meandering Pennard Pill River, which flowed south-west of the castle into Three Cliffs Bay. A rocky headland protruded from the Pennard Burrows away from the bay and overlooked the point where the Pennard Pill estuary narrowed and joined a tight and steep valley to the north. About 100 meters to the south-east there was the original parish church, but due to the sand filling the nearby dunes, the parish was moved inland already in the 15th century.

The original castle consisted of a ring of earth ramparts topped with a wooden palisade, surrounding a roughly oval courtyard measuring approximately 34 x 28 meters. From the east and south, a semicircular ditch was created, securing the approach to the castle. In the courtyard, in its western part a stone hall was erected. The plan of this building was similar to a rectangle and its dimensions were 18.6 by 7.6 meters. The shape of the building was irregular, as it narrowed towards the north. The walls of the building were well bonded with mortar, 0.7 meters thick, and the corners were rounded from the outside. The interior was divided into three rooms, the middle of which was the largest, a layout typical of the Middle Ages. The northern room probably served economic functions, the southern one was a residential room, a private one, and the middle one was a representative hall. Along the walls of the latter, there were stone benches, surrounding a centrally located hearth. Perhaps another stone, smaller building was on the south side.

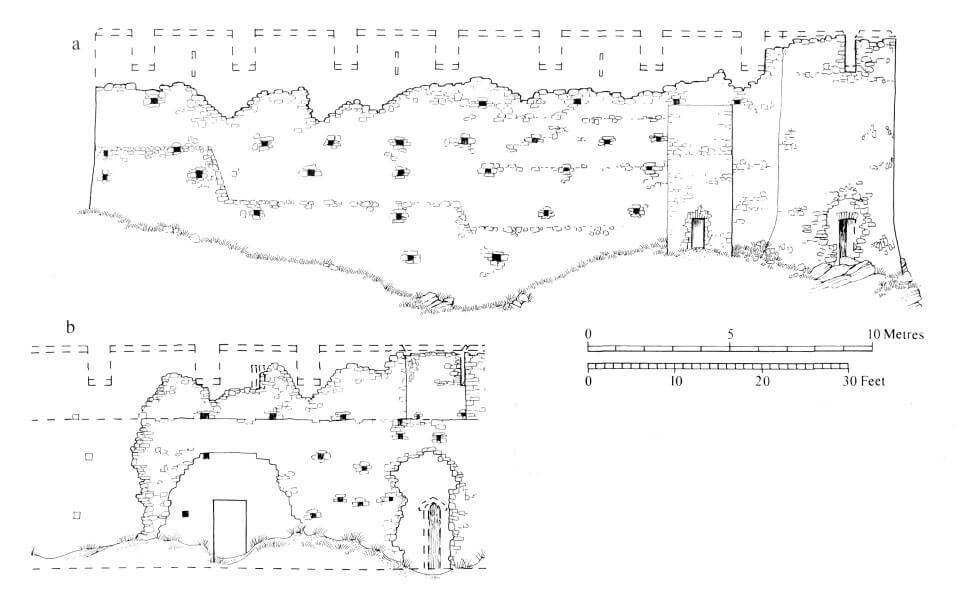

At the end of the 13th century defensive walls were erected from the local limestone and sandstone, which were created exactly on the site of older, wood and earth fortifications. The wall was 1.1 meters thick, about 8 meters high in the eastern part, and 5 meters high on the safer west side. At this level, there was a guards’ wall-walk, protected by a parapet with a battlement, with every second merlon being pierced with an arrowslit. The wall-walk had to be placed on a wooden porch, as the wall was too narrow to be placed on the offset. A characteristic feature of the curtains were numerous putlog holes, remnants of scaffolding erected during construction. On the north-west side, the defensive circuit was reinforced by a small semicircular turret, next to which there was a small latrine. The ground floor of the turret was open to the courtyard, but not connected to the second floor. The floor, on the other hand, was at the level of the wall-walk crowning the curtain.

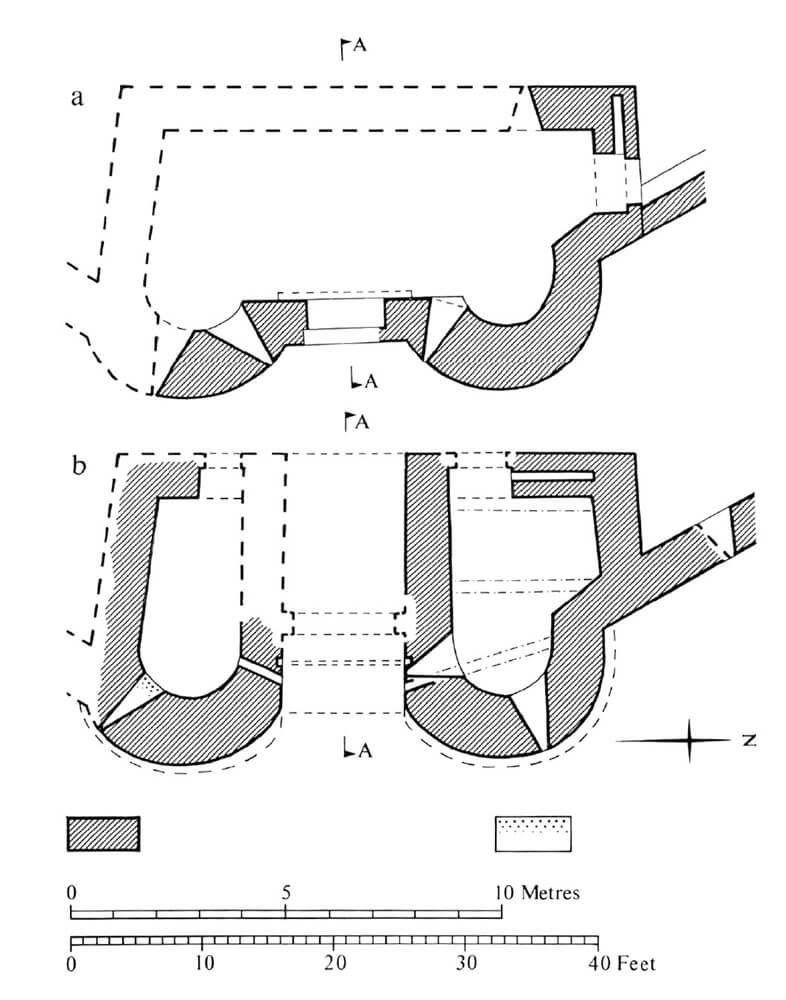

The entrance to the courtyard was on the eastern side, where a gate was placed, consisting of two horseshoe towers flanking a 2.4 meter wide passage in the middle. It was preceded by the above-mentioned ditch and a drawbridge operated by two oblique openings, and also closed with a weak portcullis (its guides ended at a height of 1.8 meters). The gate towers were about 11 meters high, 4.5 meters wide and 6.4 meters long, but they were not identical, because the northern one was extended towards the curtain. The entrance to the rooms in the ground floor of the gate led from the back of the towers, while to the upper floor on the side, via wooden, external stairs. Therefore, there was no direct connection of the guard rooms with the gate passage, and from the entrances in the ground floor only the northern one was equipped with a draw-bar. Inside, the northern room was equipped with two loop holes, one of which was directed towards the foreground and the other towards the gate passage. The southern room had only one loop hole, and it was directed to the south-east, not towards the entrance to the castle. The number of arrowslits on the first floor was also not identical: the southern tower had two, and the northern one.

In the late Middle Ages, a four-sided tower was erected in the western part of the castle. It was completely extended in front of the perimeter of the walls, had two storeys, due to its location on the slopes it was reinforced with a battered plinth and served residential functions. The room on the ground floor was illuminated by two windows splayed to the inside, one south and one west. As in the smaller turret, no stone stairs between the floors were used inside.

Current state

Until today, fragments of the ruined defensive wall have survived, mainly in the northern and north-eastern part of the perimeter, where they are visible to the level of the wall-walk, and a short fragment on the southern side. Two western towers, the nearby projection at the northern curtain and the outer wall of the double-tower gate with the relics of the walls of the northern gate tower have also survived. Admission to the ruins is free.

bibliography:

Davis P.R., Forgotten Castles of Wales and the Marches, Eardisley 2021.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Early Castles, London 1991.