History

The first seat in Penhow was established by the Seymour family, descendants of the Anglo-Norman knight Roger de St Maur, who testified to a donation to Monmouth Abbey in a document from 1129. The Seymours, who eventually grew to become one of the most prominent families in Britain, probably were endowed of the Penhow fief in the first half of the 12th century, but not before 1115, when Walter fitz Richard de Clare received power over Strigoil in the south-eastern part of the Gwent Iscoed region, under whom a system of subordinate feudal estates was established.

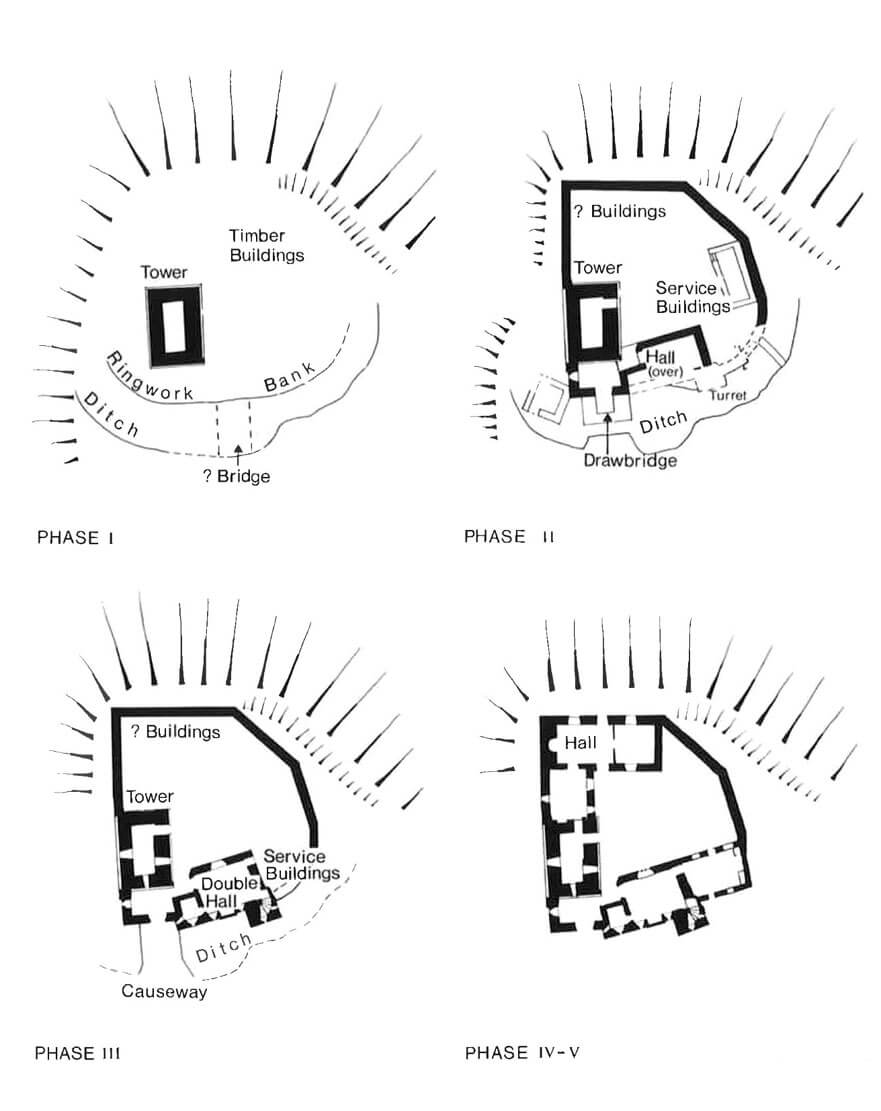

Before the end of the 12th century, one of the members of the family founded a stone tower house in Penhow. Probably in the first thirty years of the 13th century, another representative of the family, Sir William Seymour, who died in 1219, or his son of the same name, who lived until 1231, carried out an even greater expansion of the castle, then reinforced with a stone defensive wall. The expansion of the fortifications may have been the result of the military actions of the elder William, who wanted to capture the Woundy estate from the hands of the Welsh ruler Morgan ap Howel, together with Gilbert Marshal, Earl of Pembroke. Both probably also led other raids on the Welsh, because by the time of his death in 1248, Morgan had already been deprived of most of his lands. In contrast, the construction work carried out by the Seymours in the later years of the 14th century concerned mainly residential buildings, including the great hall.

Towards the end of the 14th century, the main branch of the Seymour family died out, while at the beginning of the 15th century Penhow passed to John Bowles, the husband of the heiress of the castle, Isabell Seumour. Their grandson, Sir Thomas Bowles, married Maud Morgan of Pencoed in 1482, was knighted at Berwick in the same year, and probably funded the reconstruction of the great hall, then surmounted by a panel bearing the coats of arms of Seymours, Bowles, and Morgans. These and other transformations in the second half of the 15th century, when Welsh-English tensions had diminished following the defeat of Owain Glyndŵr’s last uprising, focused mainly on improving the castle’s living conditions, at the cost of reducing its defences.

In the mid-16th century, the Penhow passed by marriage to Sir George Somerset, son of the Earl of Worcester. The early modern reconstructions of the castle may have been associated with Sir Henry Billingsley, Sheriff of Monmouthshire in the late 16th century, although neither his predecessors the Somersets, nor the Billingsleys themselves, nor their successors the Ryvetts, lived permanently at Penhow. In the early 17th century the castle was occupied by Roger Bathern and his son Richard, who probably held premises of some importance, although were only tenants and managers of the estate. Roger was sheriff in 1612, and Richard married Sir Henry Billingsley’s daughter.

Unlike most other castles in the area, Penhow survived the English Civil War of the 17th century, and was bought in 1674 by Thomas Lewis of St Pierre after a brief occupancy by Edward and George Howell. It is likely that further building works were carried out at this time, and continued under the Lloyds from 1714 onwards. In 1861 Penhow was purchased by the Perry-Herrick family of Leicestershire, and in 1914 by Lord Rhondda. In the 20th century it became the property of Stephen Weeks, who restored the historic building in 1973.

Architecture

Penhow Castle was situated in the northern, highest part of a limestone ridge, bounded by rocky and steep slopes on the north and east sides, where it fell towards the bend of the St Bride River. The outcrop was about 46 metres higher than the bottom of a narrow valley in the north, through which since Roman times a route had led from Gloucester in the east, through Chepstow, to Caerleon in the west. To the south, the castle was adjacent to a fortified outer bailey of elongated shape and the nearby church of St. John. The church occupied a small elevation of land, behind which were the peasant buildings of a small village.

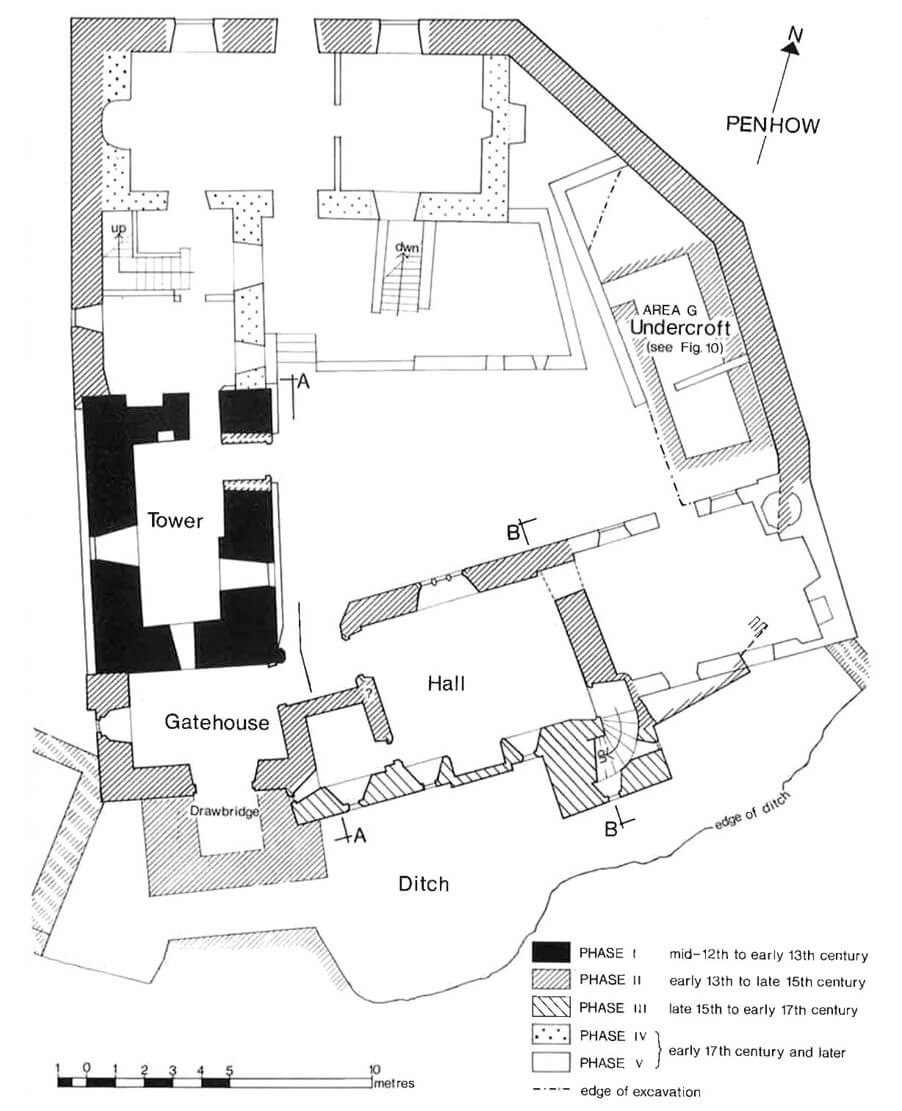

The castle fortifications outlined an irregular polygon, about 28 metres long from north to south and 23 metres from east to west. Among them, the earliest stone building was a three-storey tower house from the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, which was probably originally surrounded by a wood and earth defensive perimeter (ringwork). Access to the courtyard was possible through a gate situated on the southern side, preceded by a ditch carved in the rock. Further south there was an outer bailey measuring approximately 55 x 70 meters, surrounded by a perimeter of wood and earthen ramparts adjacent to the core of the castle in the north.

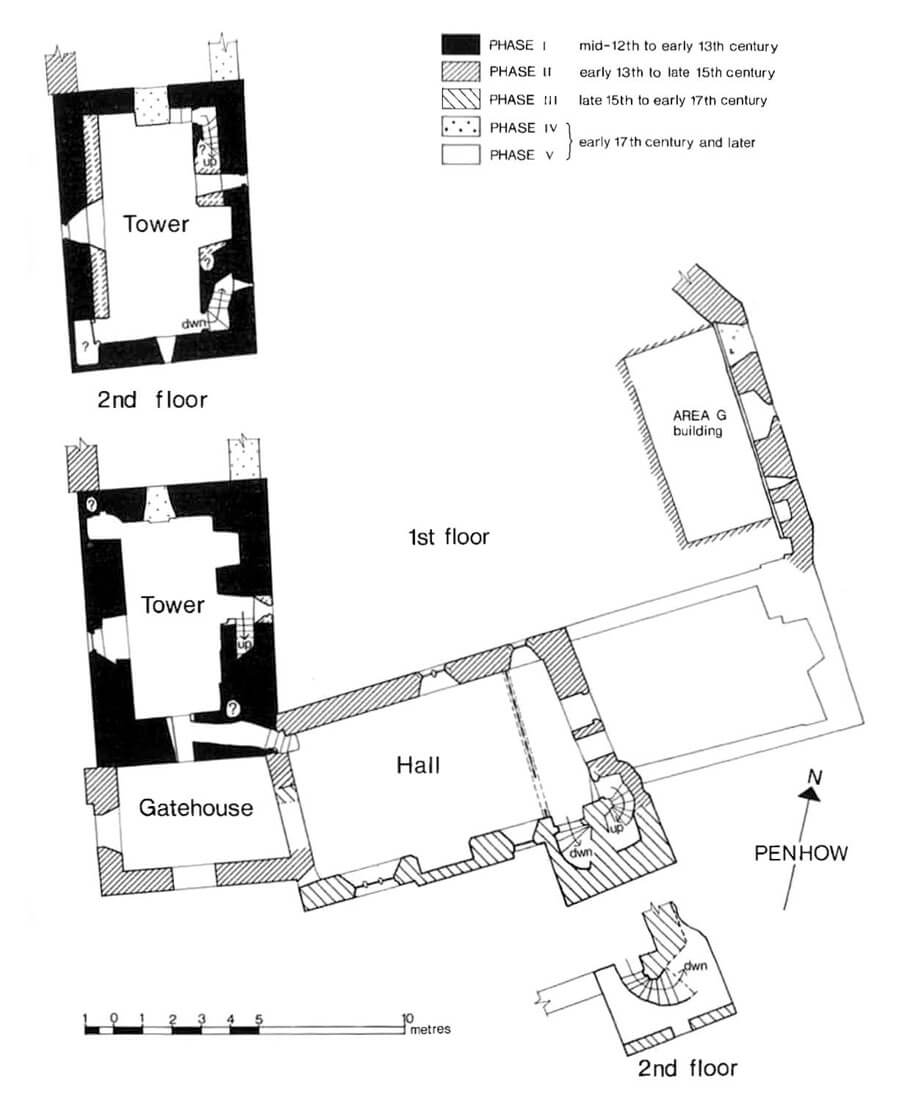

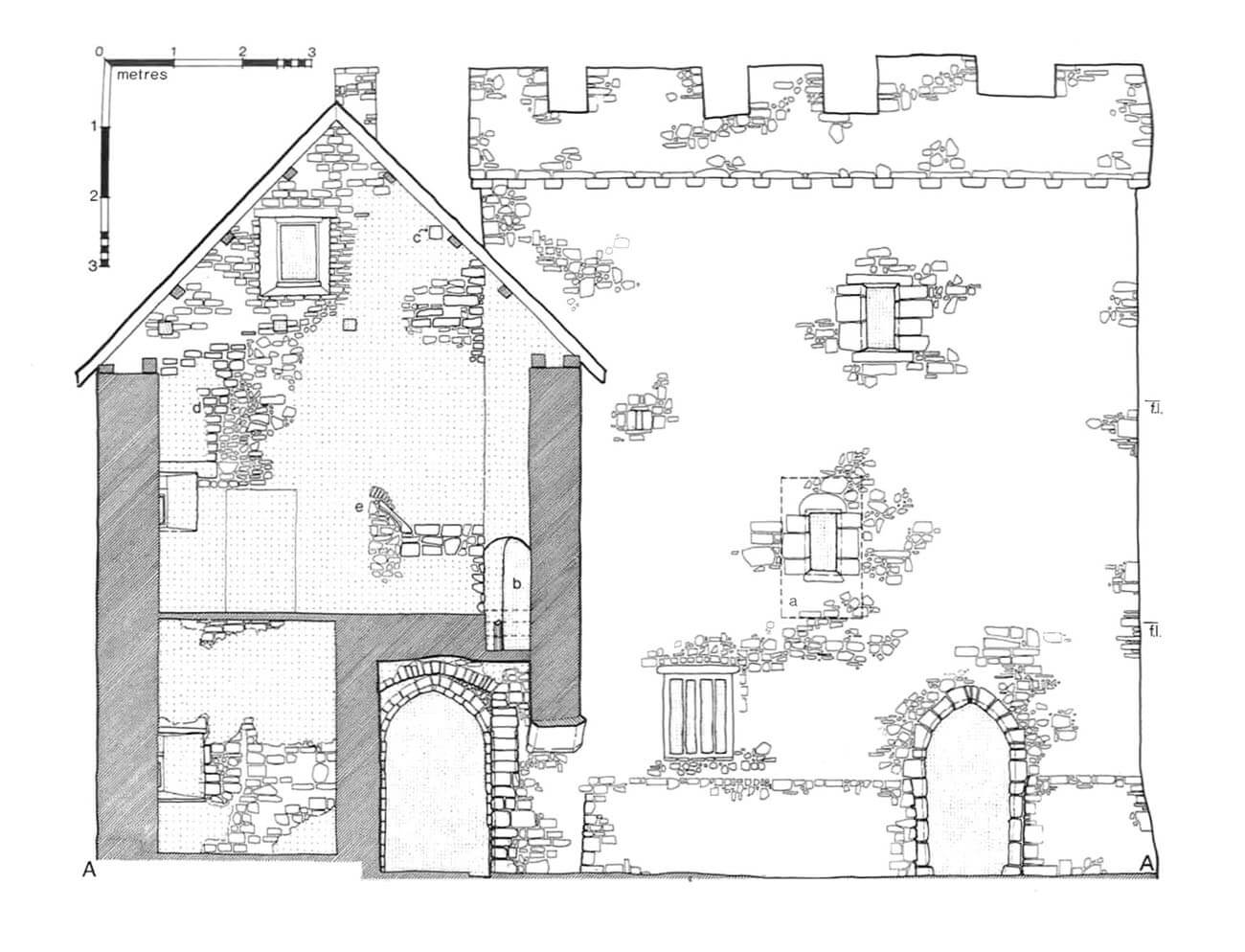

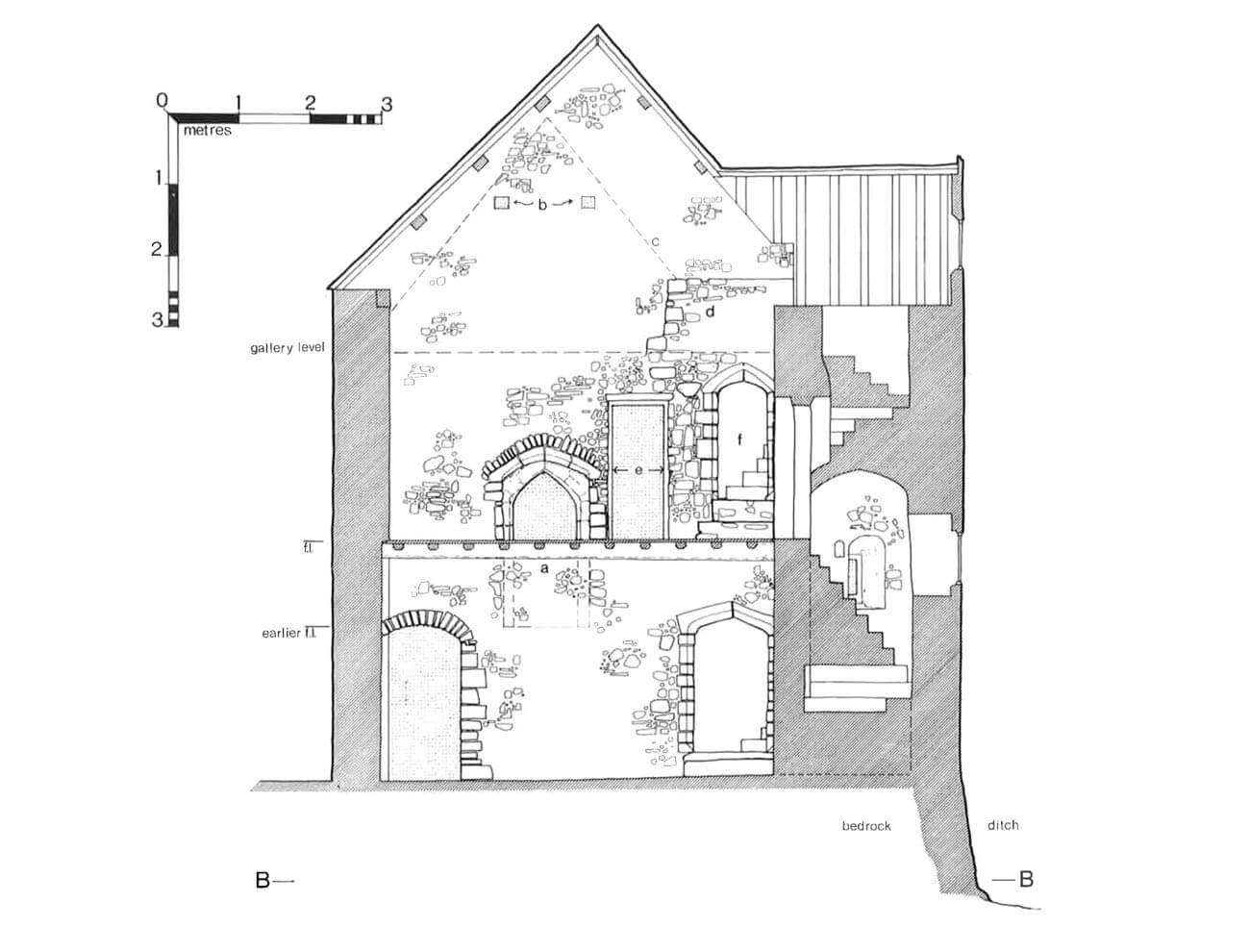

The residential tower was built on a quadrangle plan measuring 9.6 x 6.4 meters. Its walls were 1.6 meters thick, except for the more massive eastern wall, about 2 meters wide, to allow for the placement of stairs. The plinth part of the tower, in order to strengthen the structure, was battered, above which the walls were vertical. The entrance to the tower was originally located in the eastern wall on the first floor. It had to be accessed by external wooden stairs, intended to be removed in the event of a threat of attack. The earliest portal with a pointed arch and moulding along the entire height, was created on the ground floor level only in the 14th century. The few windows in the tower were small, only single-light, splayed towards the interior.

The interior of the tower was divided into three storeys separated by wooden ceilings. The lowest was a dimly lit chamber that served as a storeroom and pantry. Initially, it was accessible only by means of a ladder from the upper floor. On the second storey in the eastern wall, a vestibule in the thickness of the wall was connected to the stairs to the upper floor and to the main room. There was also a fireplace in the eastern wall of the second storey. The north-west corner probably housed a passage to the latrine, overhung on corbels on the external elevation. On the opposite side, in the south-east corner, in the 13th or 14th century, a passage to the neighboring building with a hall was made. The third storey originally had perimeter walls half as thick, which was sufficient to support a simple gable roof. They were thickened in the later Middle Ages to accommodate a wall-walk in the crown of the tower and a battlemented parapet protecting it. Entry to the battlement was provided by stairs in the north-east corner. In addition, the top floor of the tower was distinguished by a window in each wall and a recess in the south-west corner of unknown purpose, accessible through a chamfered, pointed entrance.

In the first half of the 13th century, the timber fortifications of the castle were rebuilt into a stone defensive wall set on a rocky base, topped with a battlement and a wall-walk. The gate was still located near the southern corner of the castle, where it was protected by a massive tower house. Since the 14th century, it was located in a small building with a passage in the ground floor, preceded by a 2.6 x 2 metre drawbridge. For its operation, two rectangular slots were carved in the rock, which allowed the movement of wooden arms about 2 metres long, to which counterweights were mounted to lift the footbridge. This footbridge rotated on the threshold. When raised, it sank into the recess created by the gate jambs, and when lowered it was placed on a stone pillar. After crossing it, in order to get to the courtyard, one had to turn twice, avoiding the adjacent buildings. Above the gateway there was a room, probably containing the mechanism operating the drawbridge.

Apart from the tower house, the courtyard area was probably filled with auxiliary buildings of wooden construction, attached to the fortifications from the north and east (e.g. stables, utility sheds, servants’ rooms, etc.). In the later period of the Middle Ages, a stone – wooden building was erected on the eastern side, with the lower storey partially sunk into the ground. Located 1.2 meters below the courtyard, the dark basement measured 6.7 x 3 meters, with the interior covered with a ceiling and an entrance down several steps in the northern part of the western wall. The eastern wall of the building was formed by a section of the perimeter wall, in front of which there was a shelf or platform lined with earth and rubble. The first floor of the building was located about 2 meters above the basement floor. Its part on the courtyard side may have been of wood. The lower part of the building was probably used to store wine barrels, while the upper part was probably a place of residence or work.

In the second half of the 14th century, a two-story building of a great hall was erected in the southern part of the courtyard, attached to the inner elevation of the defensive wall, equipped with a kitchen and a small pantry on the ground floor and the main representative hall on the first floor, covered with a narrow and steep gable roof. The latter, as it was larger than the main room in the tower house, was used for organizing feasts, entertaining guests, organizing ceremonies, or holding courts. Communication between the kitchen and the hall could have been provided by a small stair turret from the side of the ditch. In the 15th century, the low ground floor of the building was raised by about 1 meter to create a more spacious room. At the same time, the southern wall was demolished together with the original staircase turret and replaced by a new wall, moved slightly further south, with a new quadrangular staircase turret projecting towards the bottom of the ditch. It provided communication with the first floor, and at the same time flanked the entrance gate and protected the ditch.

Since the 15th-century reconstruction, the room on the ground floor of the southern building had dimensions of approximately 5 x 7 meters. It was entered from a curved corridor connecting the gatehouse with the courtyard. Lighting was provided from the north by a three-light window with ogee-shaped tracery and two smaller southern windows flanking the fireplace. Another window was located in the small western chamber, preserved after the reconstruction. On the first floor, the stairs opened into a narrow vestibule, separated from the main part of the hall by a wooden or half-timbered screen. The stairs continued upwards, where gave access to a gallery above the vestibule. The hall was heated by a central fireplace in the south wall. Light came through a two-light north window with trefoil tracery and two south windows, the larger of which had three-light tracery with ogee-shaped heads. Before the reconstruction, the hall was connected at first-floor level to the tower house, but the passage to it was blocked when the building was raised. However, the connection to the first-floor room of the gatehouse on the west side maintained.

Current state

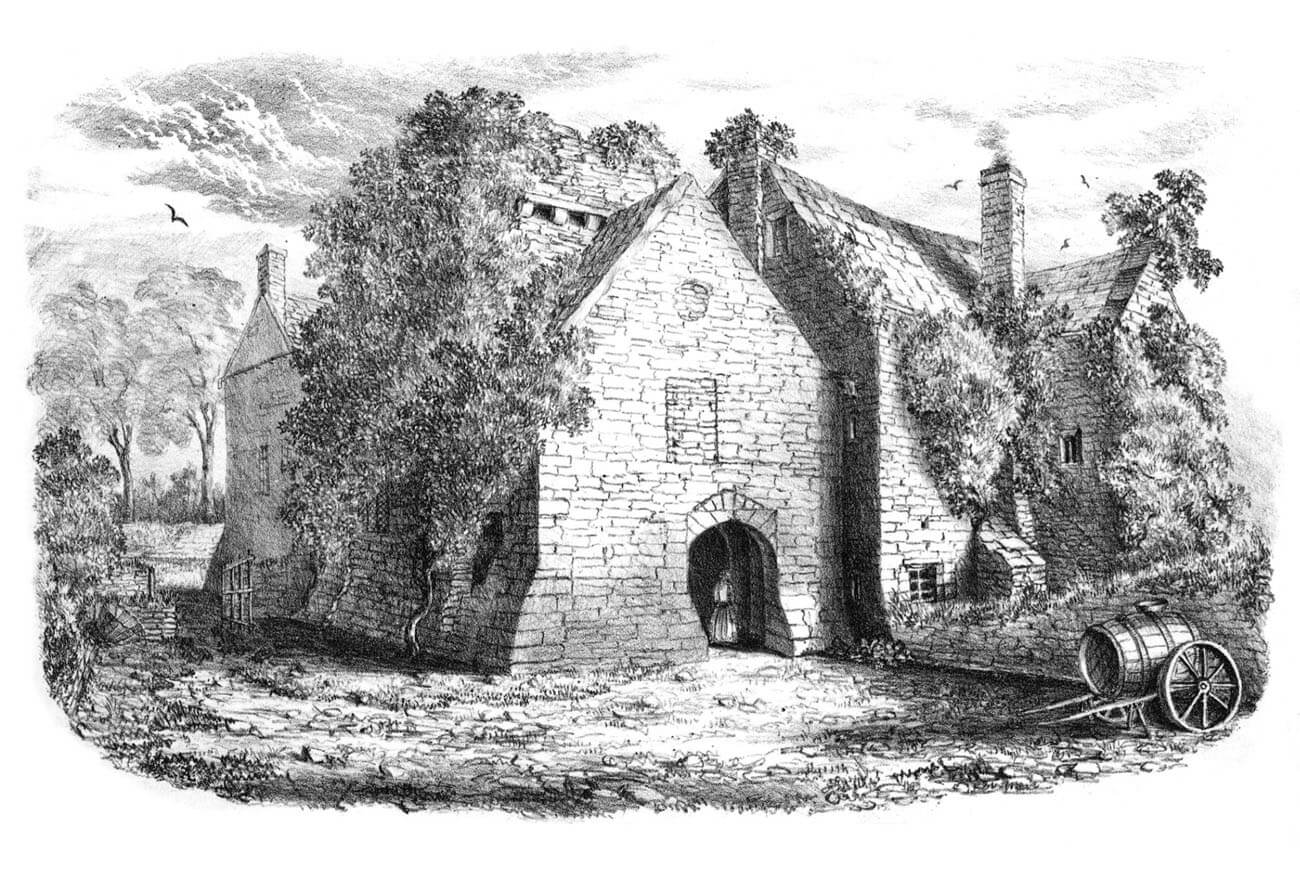

The small Penhow Castle was partially rebuilt in the 17th and 18th centuries, but work in the 20th century placed emphasis on its original features and partially restored the original character of the building. Importantly, both in the Middle Ages and in the early modern times, the need to enlarge or modernise the castle buildings was largely met by modification and extension, rather than by demolition or major reconstruction. As a result, many medieval fragments of the castle have been preserved, including the oldest tower house, the southern gatehouse and the hall. The exceptions were the medieval north and east wings, of which only the Gothic cellar remains. The entire building is now privately owned and is not open to visitors.

bibliography:

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Reed P.C., Descent of St. Maur Family of Co. Monmouth and Seymour Family of Hatch, Co. Somerset, “Foundations”, 2(6)/2008.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

Wrathmel S., Penhow Castle, Gwent: Survey and excavation, 1976-9: Part 1, “Monmouthshire Antiquary”, 6/1990.

Wrathmel S., Penhow Castle, Gwent: Survey and excavation, 1976-9: Part 2, “Monmouthshire Antiquary”, 32/2015.