History

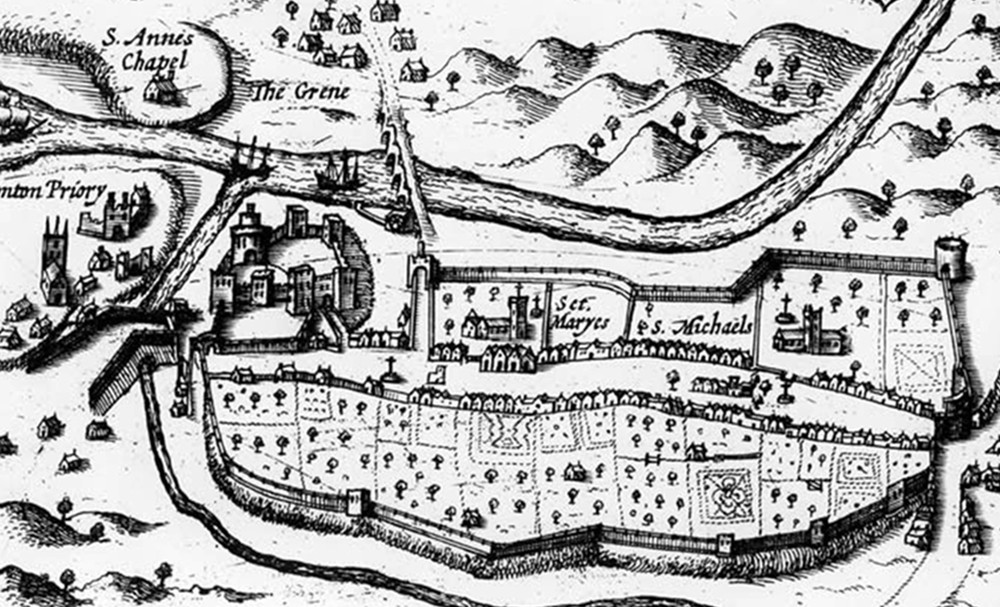

Pembroke’s stone walls were built at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, but were preceded by older fortifications that surrounded a small area between the parish church and the castle. Pembroke was founded in 1093 by the Anglo-Norman adventurer Roger de Montgomery, who invaded West Wales after the death of its native ruler, Rhys ap Tewdwr. Roger’s son, Arnulf, subjugated the surrounding areas, but before he could consolidate power, his estates were taken over by King Henry I in the early 12th century. After evicting the native population and replacing them with colonists from the west of England, the ruler granted the settlement a town charter between 1102 and 1135. In 1138, one of the leading Anglo-Norman barons, Gilbert de Clare, was created Earl of Pembroke, which became the centre of an earldom with semi-autonomous status until the end of the Middle Ages. For this reason, the Pembroke fortifications were no longer subject to the murage grants, i.e. permissions from English rulers to raise money for their construction, obtained primarily from exemptions from taxes and other duties.

Probably at the beginning of the 13th century, when the suburbs of the settlement developed under William Marshal, the fortifications were extended to St. Michael’s Church to the east. However, it were still of timber and earth construction. It is unlikely that the building of the town’s stone fortifications began before the construction of the stone fortifications of the castle outer bailey, on which work was underway in the time of William de Valence, the first Earl of Pembroke of the third creation. William began rebuilding the castle after 1257, on the royal order of his half-brother, King Henry III, and completed it around 1280. It is possible that during this stage of the work the older western part of the town gained stone fortifications, but it was not until the expansion at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, during the time of William’s son, Aymer de Valence, that the entire town was surrounded by a stone perimeter of fortifications.

In the second half of the 14th century and in the 15th century, the town walls of Pembroke had to undergo repairs. In 1377, the constable of the castle, Degarey Seys, was commissioned to carry out measurements, repairs and fortify the castle and town, which would indicate that the town fortifications were in poor condition or even were unfinished at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. The abandonment or slowdown of construction may have resulted from the weakening of the original initiative during the long absences of the lords in Pembroke after the mid-14th century and the economic weakness of the townspeople. Further repair and construction works must have been carried out after the damages caused during the Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr in the early 15th century, although this was not recorded in documents. The town fortifications were not mentioned until 1479-1480, when 24 shillings and 4 pence were spent on a section of wall in the southern part of the perimeter. In 1480-1481, there was a record of destroyed residential buildings, that were too close to the fortifications at the time of the uprising and had not yet been rebuilt. In 1482, bailiff of Pembroke asked for support for the repair of the wall, which was carried out from the foundation level, paying for 96 loads of lime, 5 loads of gravel and a carriage of stone. In 1543-1544, 14 shillings and 8 pence were spent on various repairs to the eastern gate.

In the first half of the 16th century, the town lost its semi-autonomous status and gradually fell into decline. In 1610, the English cartographer John Speed recorded that he saw more uninhabited houses in Pembroke than in any other town during his travels. In such a situation, the town walls were certainly no longer maintained, especially since even the castle itself was no longer garrisoned. Although pirate attacks and French invasion were feared, the authorities relied for defence on the county’s early modern fortifications dating back to Henry VIII. Hasty repairs and partial reconstruction of Pembroke’s fortifications were not carried out until the English Civil War of the 1640s, thanks to which an assault on the town, made using ladders, was repelled in 1648. However, a siege in the same year by Oliver Cromwell’s better equipped troops led to the fall of Pembroke. The troops shelled the town for several weeks, causing significant damage to both the castle and the town walls. In addition, after the fighting ended, Cromwell ordered the deliberate demolition of the fortifications to an unknown extent. Although the Pembroke revived economically in the 18th century, no one considered investing in the outdated walls. It became a source of free building material and a target for demolition to improve communication.

Architecture

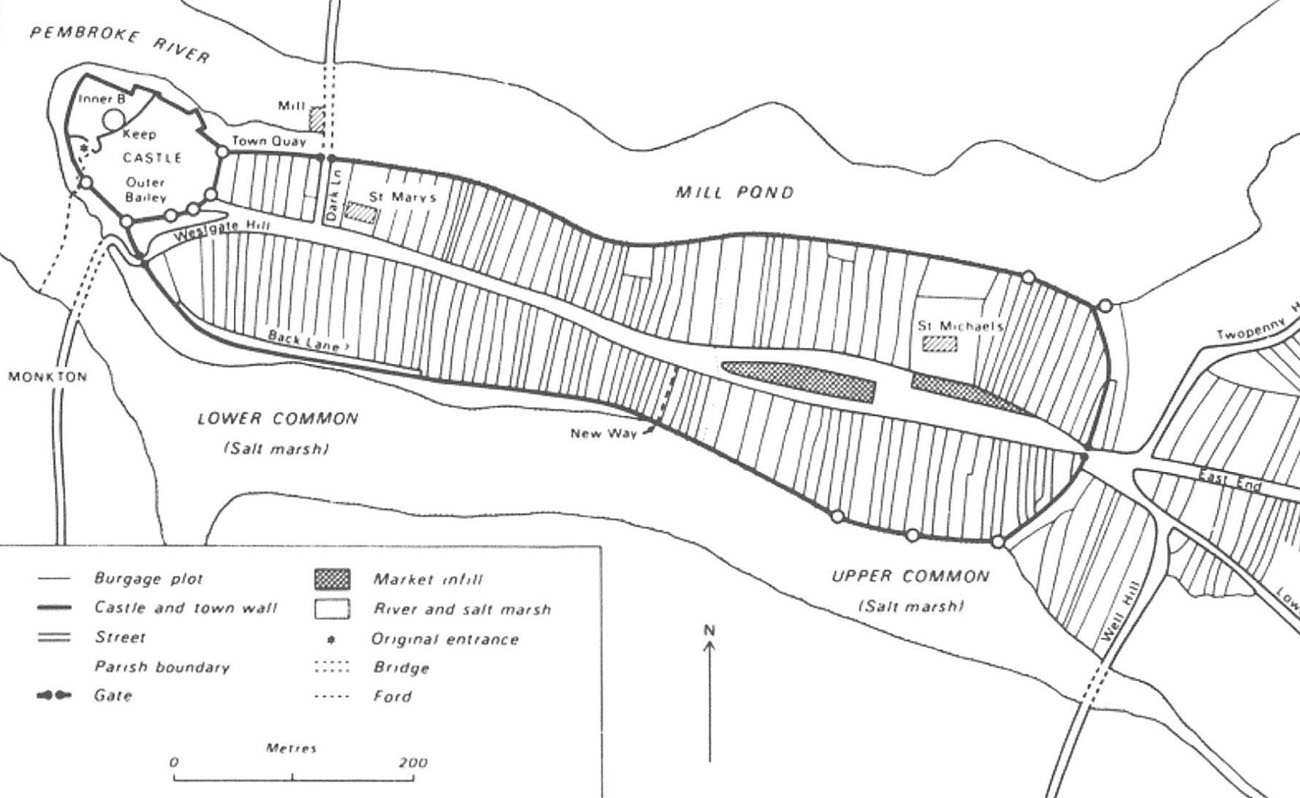

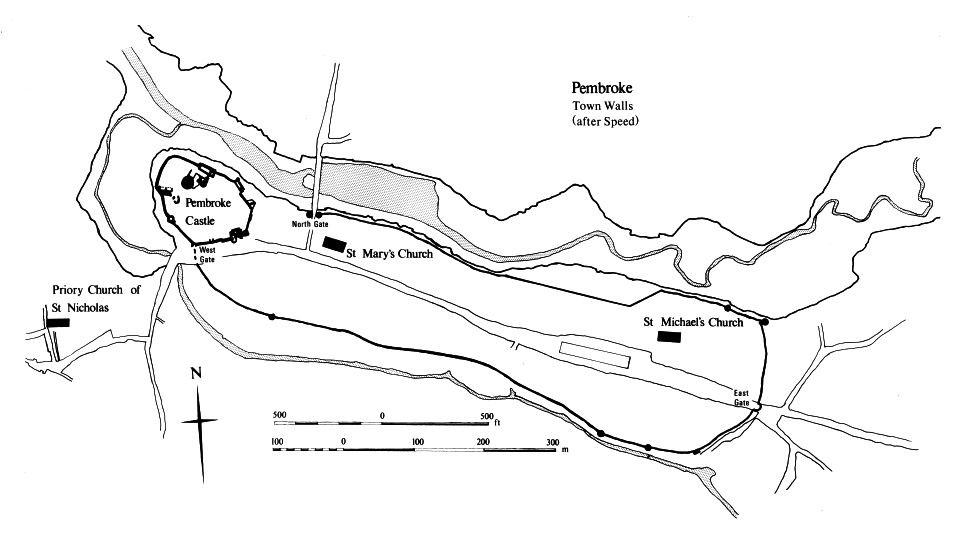

The town was founded on a limestone ridge, on a plan of an elongated polygon on the east-west axis, with a distinct narrowing in the middle, probably resulting from the gradual expansion of the fortifications. The area covered by the walls was about 850 meters long and a maximum of 240 meters wide. From the north it was limited by the elongated Mill Pond, spilled on the Pembroke River, and from the south by the small Monkton Pill stream, which joined the pond in the west. The low terrain along the southern stream was difficult to cross, covered with salt marshes and often flooded. Only the short eastern section was devoid of major natural obstacles. On the north-west side, the rocky riverside promontory was occupied by a castle, whose fortifications met two curtains of the town wall.

The limitations of the terrain influenced the linear form of the town, laid out basically along one long street, widening in the eastern part, where it included the mid-market development, leading from the castle in the west to the gate in the east, beyond which the routes from Carmarthen and Tenby joined. The short transverse streets of the town led only to the bridge over the Pembroke River and to the gate at the foot of the castle, the latter being basically an extension of the main road on the axis of the town. Along both sides of it were narrow and long burgher plots, which reached the line of the fortifications, leaving no room for an uderwall street. However, the medieval town did not have dense development, so the rear parts of the plots were probably occupied by orchards and gardens, which facilitated access to the defensive walls. The plots in the eastern part of the town were clearly wider than those in the western part, which would indicate, like the central narrowing of the defensive perimeter, the staged development of Pembroke and its fortifications. The town was finally formed in the first half of the 13th century, after the market suburb with St. Michael’s Church had been absorbed into the older part of the settlement with St. Mary’s Church.

The Pembroke town defensive wall was built of rubble, mortared limestone of medium size. It was probably topped by a wall-walk and a battlemented parapet protecting it from the foreland, with the walk being on an offset rather than a wooden porch. Presumably on the most endangered eastern section, the furthest from the castle and the only one without water obstacles, the wall was preceded by a moat in the form of a dry ditch. On most of the perimeter wall was characterised by very long curtains, with numerous sections rounded to adapt to the shape of the terrain.

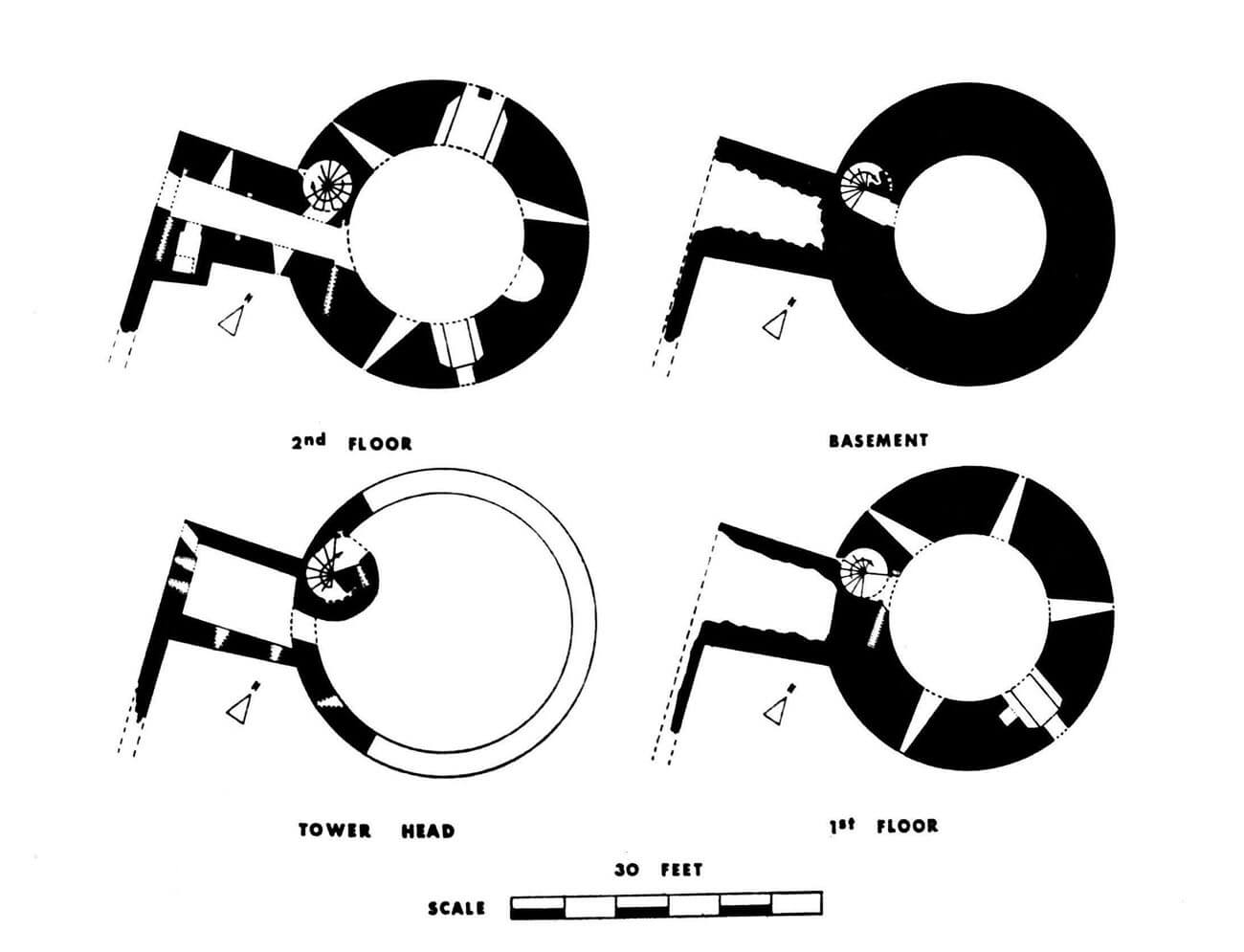

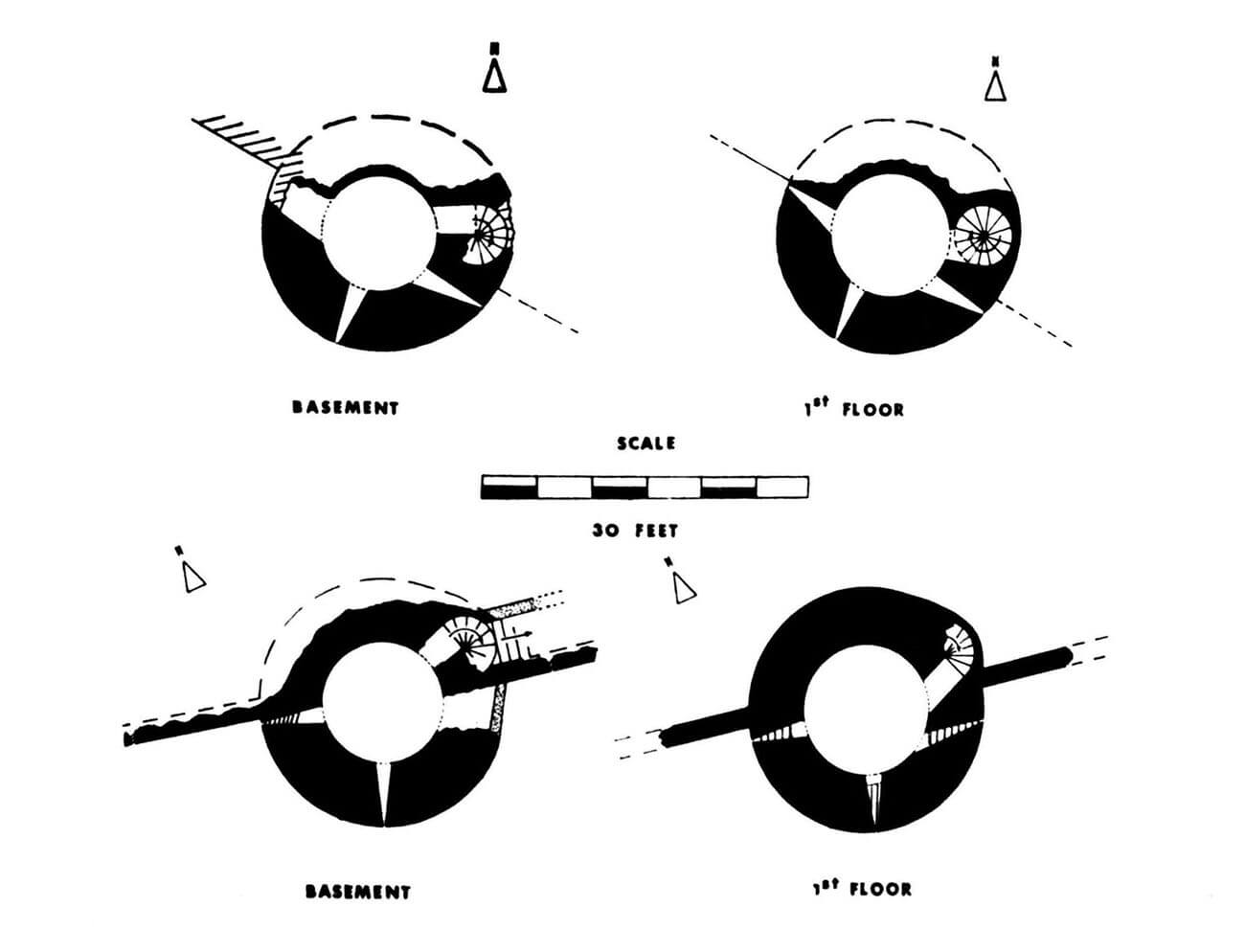

The perimeter of the wall was reinforced with at least six towers. The eastern part, the furthest from the castle, was the most heavily fortified. On the north-eastern side there were two cylindrical towers, and on the south-eastern side three, placed at intervals of about 19 meters. A single tower was also placed in the south-western part of the fortifications. Most of them had a diameter of about 6-7 meters and protruded in front of the face of the wall. It were probably not too high, at most exceeding the height of the defensive wall by one storey. Their walls were pierced with radially placed loop holes, of which on each storey one was directed into the foreground, and two more flanked the adjacent sections of the curtain walls. Internal communication was provided in the towers by spiral staircases embedded in the thickness of the walls, for which a slightly thicker section of the wall had to be created in at least two towers, slightly distorting the cylindrical plan.

The corner, north-eastern tower, called Bernard’s Tower, had a unique form compared to the others. It was built on a circular plan with a diameter of about 8.8 meters, with a wall 2.1 meters thick. It was completely protruding in front of the town walls, to which it was connected by a short, straight curtain. It had three storeys, an external latrine on massive corbels and a fireplace inside to serve as living quarters in times of peace. The room with the fireplace was topped with a dome vault. Its lighting was provided by two windows with side stone seats, one of which was two-light. It was also equipped with three slit-shaped loop holes splayed towards the interior. The entrance from the walk in the crown of the wall was preceded by a short, vaulted passage. Interestingly, it was closed with a bar set in an opening in the wall, a portcullis and perhaps a small drawbridge, which could have made the tower an independent point of resistance. The passage was connected to the aforementioned latrine and to a spiral staircase leading to a lower floor with four loop holes and a slightly larger window with seats. Below was a dark cellar without any openings, while the stairs led up to the combat floor at the very top of the tower.

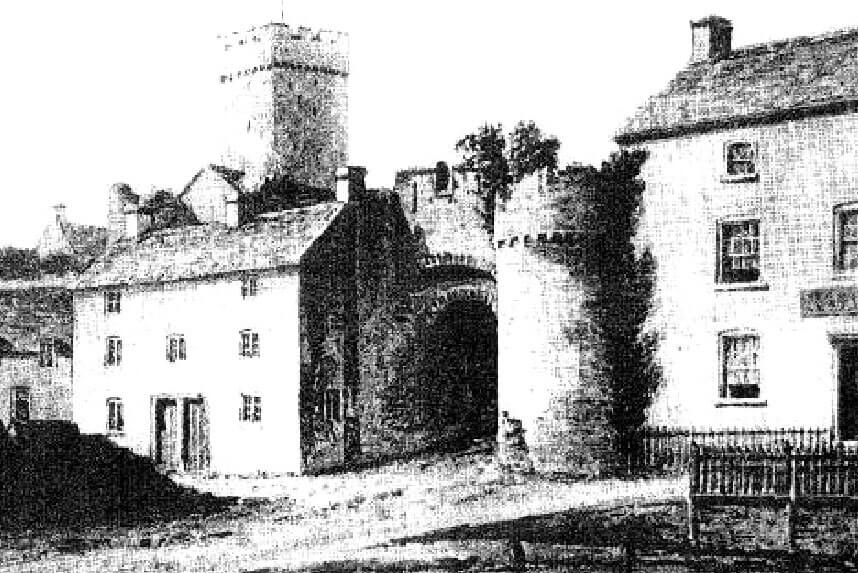

Three gates led to the town: the western gate located south of the castle, in close proximity to it, the Water Gate located east of the castle in the northern part of the perimeter, facing the mill pond, and the eastern gate furthest from the castle. In addition, communication was facilitated by at least two smaller posterns, recorded in the second half of the 15th century. The eastern and western gates were located at the end of the main road running through the city. The northern gate stood just before the bridge crossing at the end of a short transverse street. It was a typical structure for the early 14th century, equipped with two towers flanking the passage between them, above which there was a parapet set on an arcade, probably with the function of a machicolation. The eastern gate could have had a form similar to the gate complex of the castle outer bailey, where in the 14th century a rounded barbican was created at one of the towers.

Current state

The Pembroke town fortifications, together with the castle form one of the most visually impressive medieval architectural complexes in the south-west of Wales, equal to the Edwardian towns and castles in north Wales. Fragments of the defensive walls have survived in the southern and south-eastern parts of the perimeter, where relics of two towers are also visible, one of which is topped with a modern structure in the form of a gazebo. Another longer fragment of the fortifications is located in the north-eastern part of the perimeter, where two towers have survived, including the so-called Bernard’s Tower, currently the best-preserved element of the Pembroke fortifications. Of the town gates, only relics of the western gate are visible (the northern gate was slightened around 1820, the western and eastern gates, after destruction during the civil war, were finally removed in the 18th century).

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

King D.J.C., Cheshire M., The town walls of Pembroke, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 131/1982.

Ludlow N., Pembroke castle. Birthplace of the Tudor dynasty, Pembroke 2001.

Ludlow N., Pembroke town walls project, archaeological interpretation and condition survey, Pembroke 2001.

Salter M., Medieval walled towns, Malvern 2013.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.