History

The place where Pembroke Castle was erected was already inhabited during the Paleolithic period, fortified in the Iron Age, and then used in Roman times and in the early Middle Ages. When the Welsh king Rhys ap Tewdwr was killed in a border skirmish in 1093, the Norman baron Roger de Montgomery took the opportunity to occupy South West Wales. After the conquest, he built castles in Cardigan and Pembroke, of which the latter was a wooden stronghold built using earthworks of an earlier iron age fort. Under the Arnulf, the younger son of Roger de Montgomery, Pembroke was the only stronghold in the region that did not fall during the battles with the Welsh in 1094.

Due to internal conflicts in England, specifically Arnulf’s involvement in the rebellion of his brother Robert de Bellesme, in 1102 Pembroke Castle was occupied by King Henry I, who put the sheriff in it and founded the town at its foot. The first sheriff was a Saer, dismissed after three years and replaced by Gerald de Windsor, while the castle remained royal property until 1138, when King Stephen created the earldom and granted it to a member of his entourage, Gilbert de Clare. His son and successor, Richard de Clare called Strongbow, in 1169 used Pembroke as a base to launch an invasion of Ireland. This unauthorized action and Strongbow’s proclaiming Lord of Leinster caused the wrath of Henry II, who personally intervened in Ireland and confiscated Pembroke. It was briefly given to the prince (later king) John, but eventually in 1176 Richard de Clare managed to regain the favor of the monarch, titles, lands and the castle. He held Pembroke until his death, in the same year, after which, due to the childless death of his only son, the castle returned to the king.

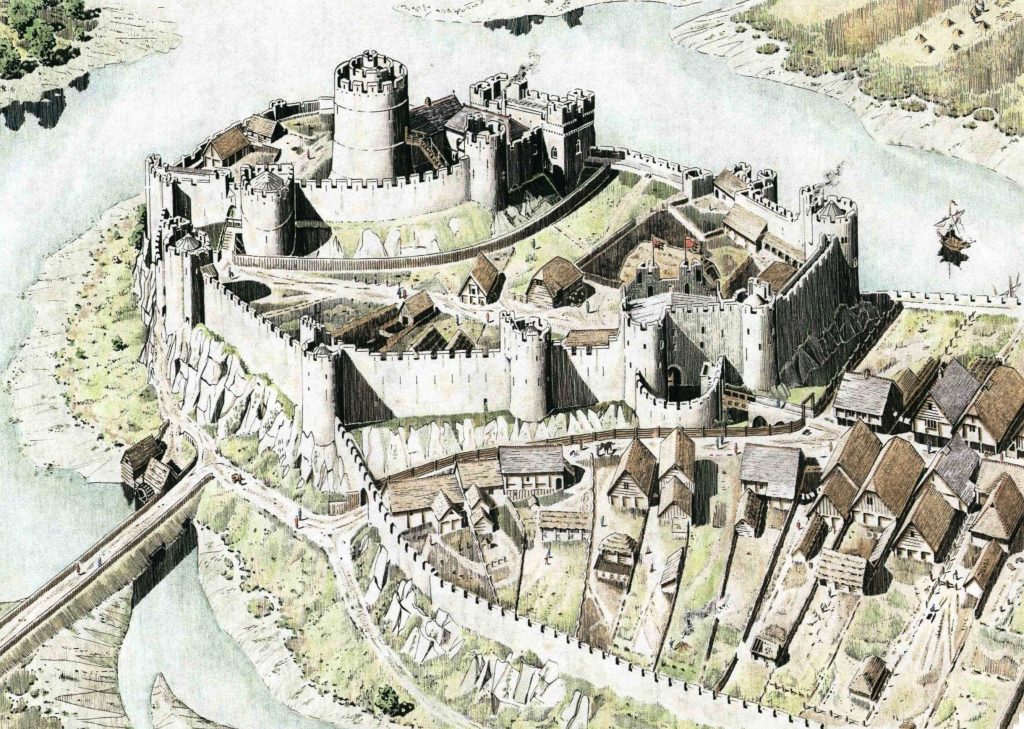

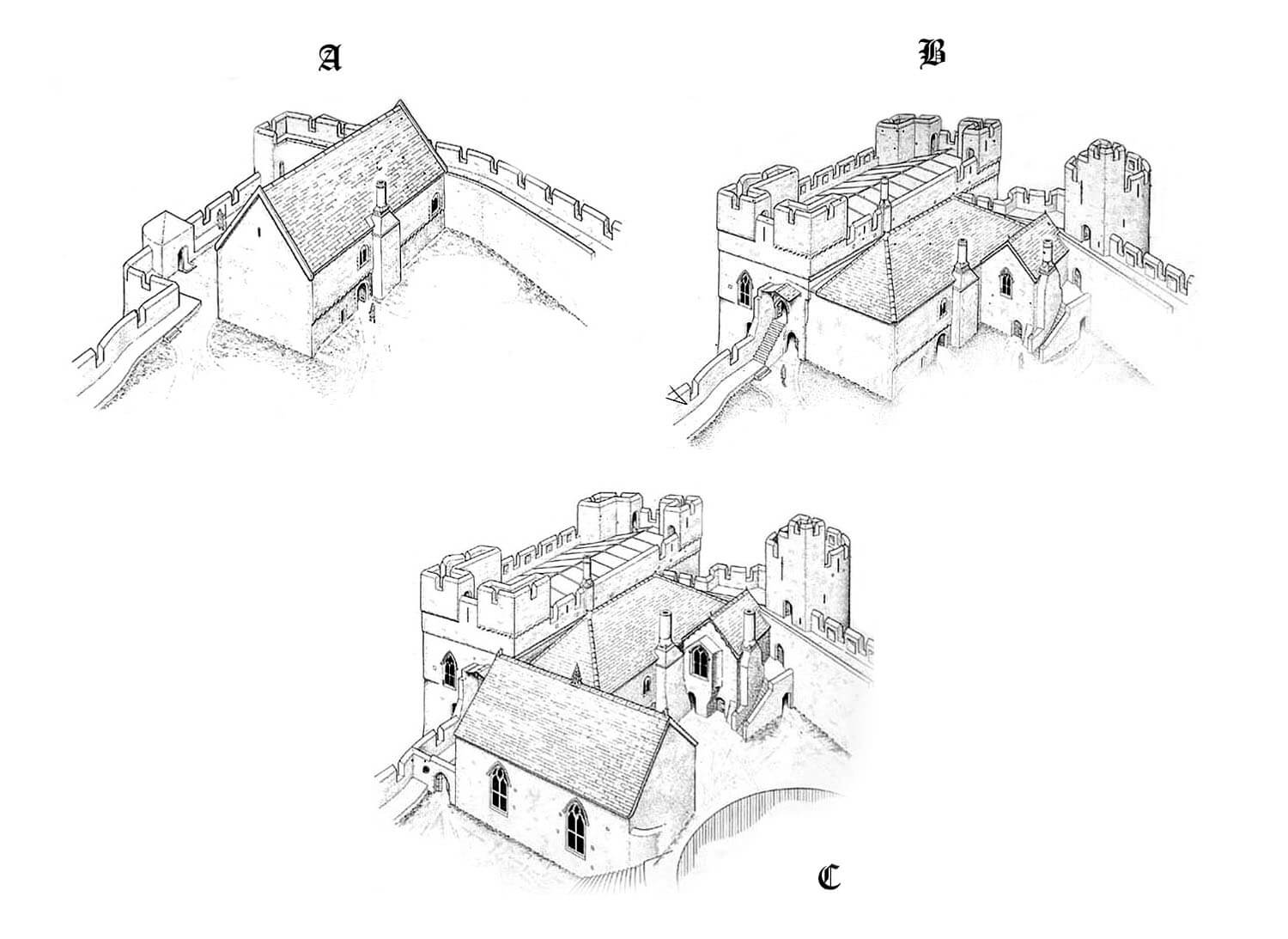

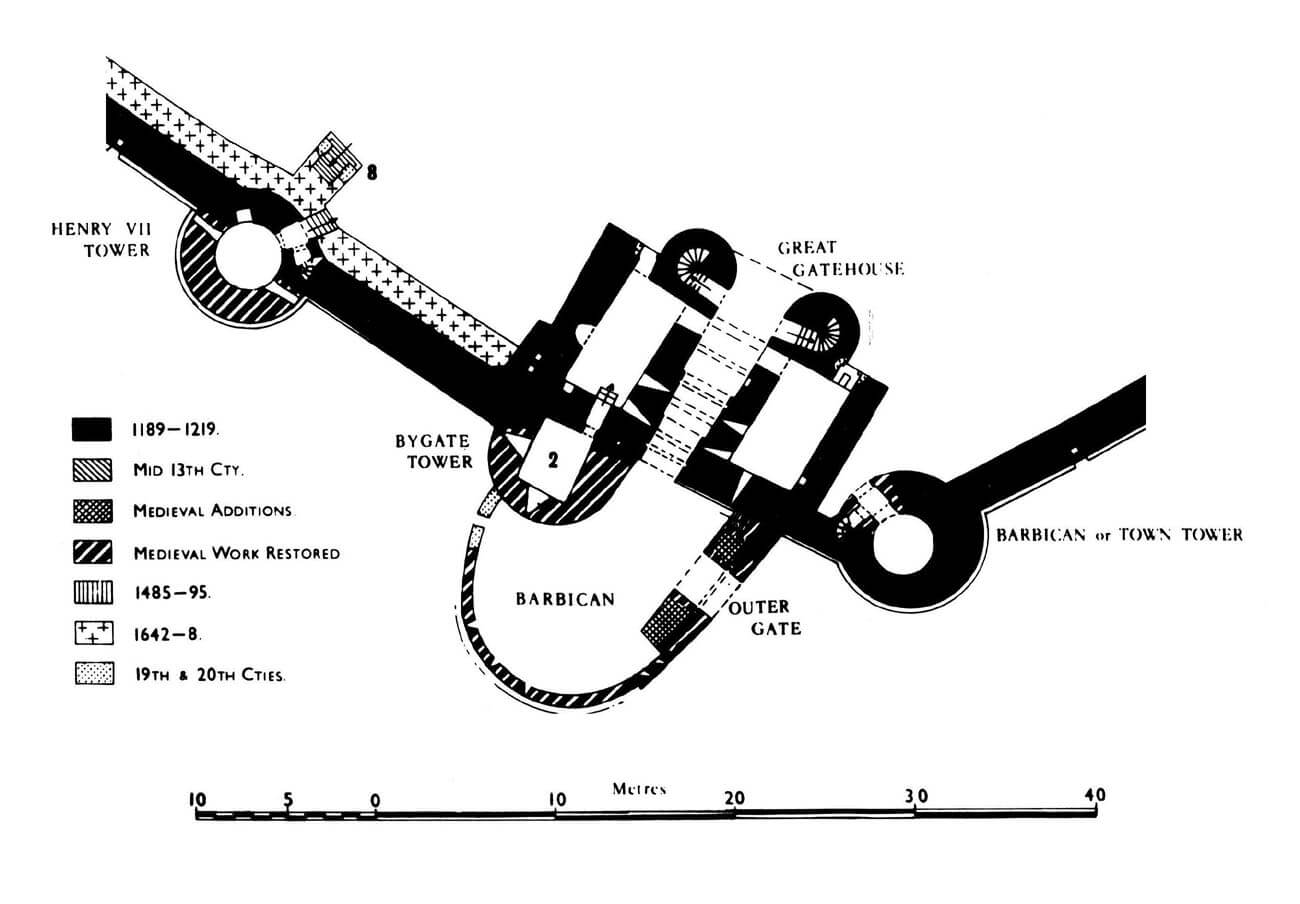

In August 1189, King Richard the Lionheart arranged the marriage of Isabella, daughter of Richard de Clare, to William Marshal, who received both the castle and the title of Earl of Pembroke. The new owner was not able to quickly take possession of the castle. It wasn’t until 1199 that he received confirmation from John, and he could come to Pembroke at the earliest in 1204 after returning from the war campaign in Normandy. During this period, Pembroke, as one of the few Anglo-Norman strongholds, did not fall into the hands of the Rhys ap Gruffydd, regaining the lands lost to the invaders. Rhys’s death in 1196 caused even greater confusion in the region and the need for William Marshal’s personal arrival in Pembroke. On his initiative, at the beginning of the thirteenth century, the construction of a stone castle began. Among others, a massive keep was built and the timber buildings at the town were expended, which after moving to further areas freed up space for the outer ward. When Marshal went to Leinster without King John’s permission in 1207, his castles were confiscated. It returned to him around 1211-12, and in the meantime at Pembroke in 1210 the king had gathered an army on its way to Ireland, which would indicate the castle’s importance and the capacity to house a considerable number of troops.

William Marshal died in 1219. The castle was inherited by each of his five sons, whose third son, Gilbert Marshal, was responsible for enlarging and strengthening the castle between 1234 and 1241. Ultimately, all of Marshal’s sons died childless, and in 1247 the castle was inherited by William de Valence, Henry III’s half brother, who became the earl of Pembroke through marriage with Joan, granddaughter of William Marshall. Enjoying the terrible opinion of the arrogant, cruel and boastful feudal lord, after 1260 William de Valence began rebuilding the outer ward, replacing timber and earth fortifications with stone walls and erecting new residential and representative buildings at the upper castle at the end of his life.

During the two wars of Welsh Independence in the second half of the 13th century, the castle became de Valence’s base to fight the Welsh princes. Although the south-west of Wales was not directly involved in major military operations, the eldest son of William de Valence, also named William, was killed during a skirmish at Carmarthen in 1282. By the end of the century, Wales was already pacified, which significantly reduced the military importance of the castle. William de Valence died in 1296, and his son Aymer de Valence in Pembroke was probably only once, in 1323, leaving the castle to administrators and officials. When he died a year later, his property passed through marriage to the Hastings family, who owned the castle until 1389, until the childless death of John Hastings during the tournament. Then Pembroke again became royal castle, this time of Richard II. In the possession of the monarch at the castle deteriorated during the Hastings era, repairs were carried out, necessary because the building was intended for Pembroke County court sessions and because of fear of a French landing. At that time, the garrison of the castle was to consist of 190 people under the command of constable Degarrey Says.

At the beginning of the 15th century, Owain Glyndŵr began the great uprising of the Welsh. Pembroke escaped the invasion because the then administrator of the castle, Francis а Court, paid Glyndŵr a tribute in gold, and the rebellion was suppressed after a few years. In 1413, King Henry V recreated the title of Earl of Pembroke, which was given to the brother of the monarch, Humphrey Plantagenet, duke of Gloucester. He died in 1447 in custody for allegations of treason and for maintaining contacts with the accused of witchcraft Eleanor Cobham. His successor for a short period was William de la Pole, a duke of Suffolk, who died enigmaticly in exile in France. In 1452 the castle and the count were handed over to Jasper Tudor, half brother of King Henry VI. Tudor brought to Pembroke his widowed sister-in-law, Margaret Beaufort, who in 1457 gave birth to her only child, who in the future would become King of England Henry VII. Jasper also became a great benefactor for Pembroke, the first since the time of William de Valence, renovating the castle and modernizing living its quarters.

The second half of the fifteenth century and the sixteenth century passed for Pembroke in peace. During the War of Roses, the castle did not play a military role, but was only used as a reward for loyal supporters. During the York triumph in the years 1461-1462 it was given by the new king Edward IV to William Herbert. After the Lancaster defeat at Barnet in 1471, Jasper Tudor fled to Pembroke, where he was most likely besieged by York troops, but he managed to escape to France with Henry Tudor. After the end of the internal conflict between the Yorks and Lancasters, the rule of the new Tudor dynasty of Welsh origin, alleviated the hostility of the English and Welsh, and as a consequence with the development of firearms, the castle lost its significance.

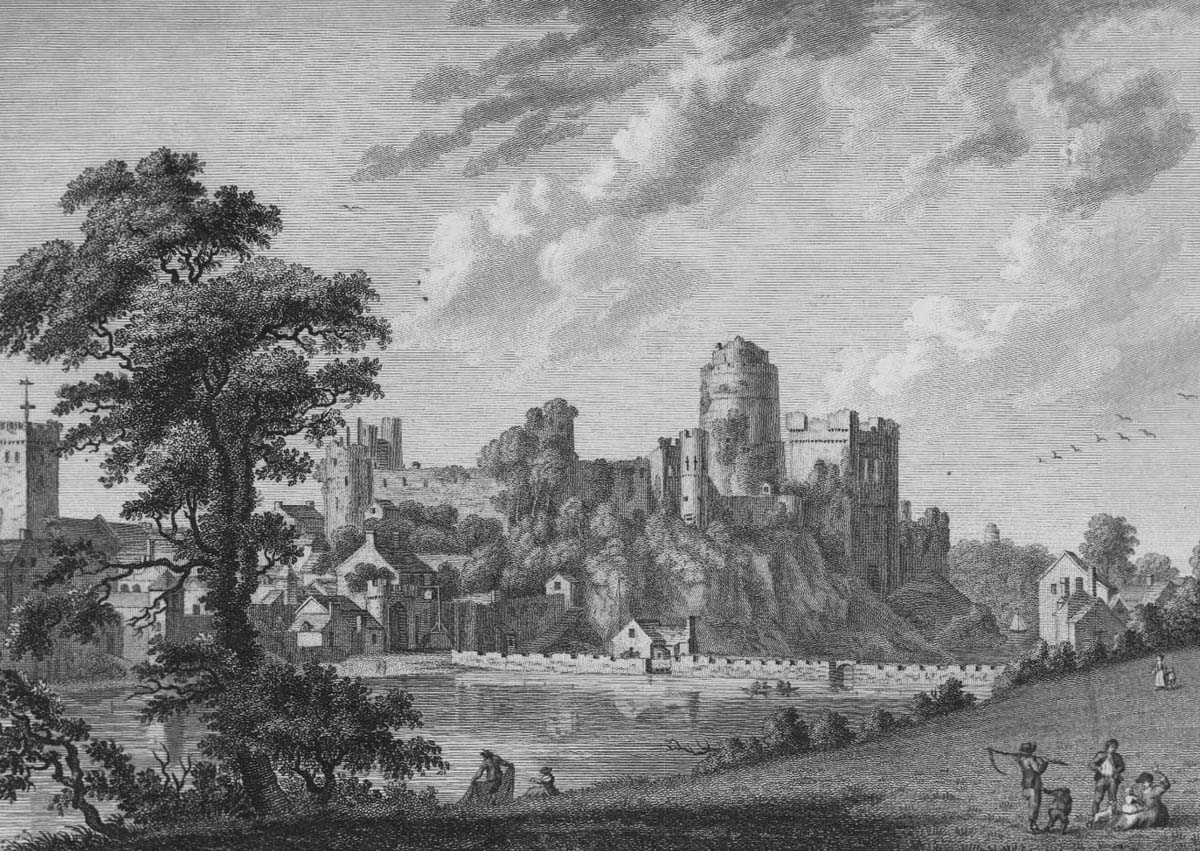

In the 1640s Pembroke Castle was used in military operations for the last time. Although most of South Wales was on the king’s side, Pembroke opted for Parliament. It was besieged by royalist troops, but was saved by the relief from nearby Milford Haven. The parliamentary forces then seized the royalist castles of Tenby, Haverfordwest and Carew. In 1648, when the war was over, the leaders of Pembroke changed sides and unwisely raised the royalist uprising. In reaction, Oliver Cromwell captured the castle after the seven-week siege. Its three leaders were found guilty of treason, and Cromwell ordered the destruction of the castle. It was abandoned and allowed to fall into ruin. It was not until 1880 that the first three-year renovation project was undertaken, and then in 1928 General Ivor Philipps acquired the castle and began its general renovation.

Architecture

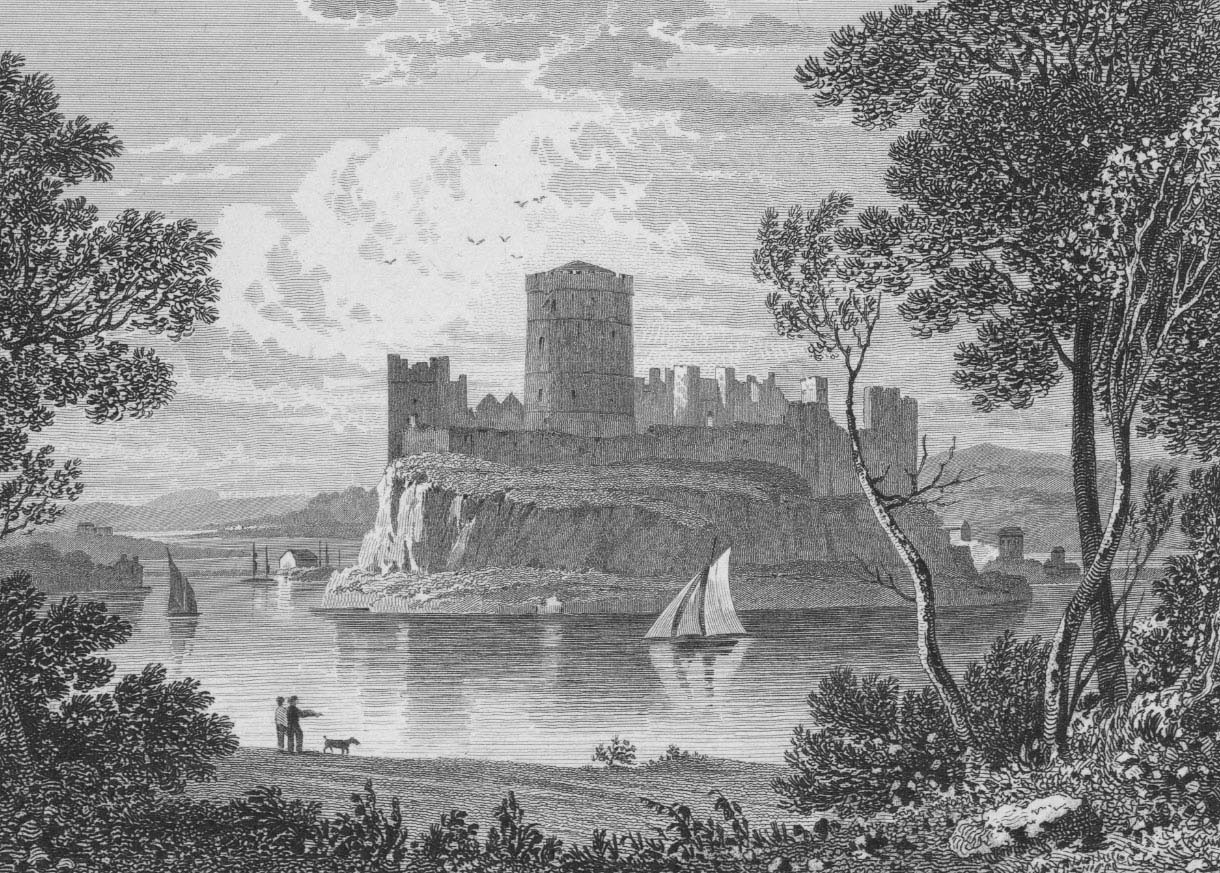

The oldest fortifications of the castle were erected on a rocky promontory about 12 meters high and about 150 x 100 meters in size, originally surrounded from the south and north by two watercourses, the smaller Monkton Pill stream and the Pembroke River, which after connecting in the north-west flowed into the wide Milford Haven estuary. The river to the north was eventually transformed into an elongated pond. After the construction of the mill dam it spread over the entire northern section of the castle and the town. The original wood and earth fortifications of Pembroke consisted of a palisade and an earthen rampart, cutting a semicircle across the edge of the promontory on the south-east side. From the other directions, i.e. from the west, north and partly south, protection was provided by high and steep slopes falling directly into the water.

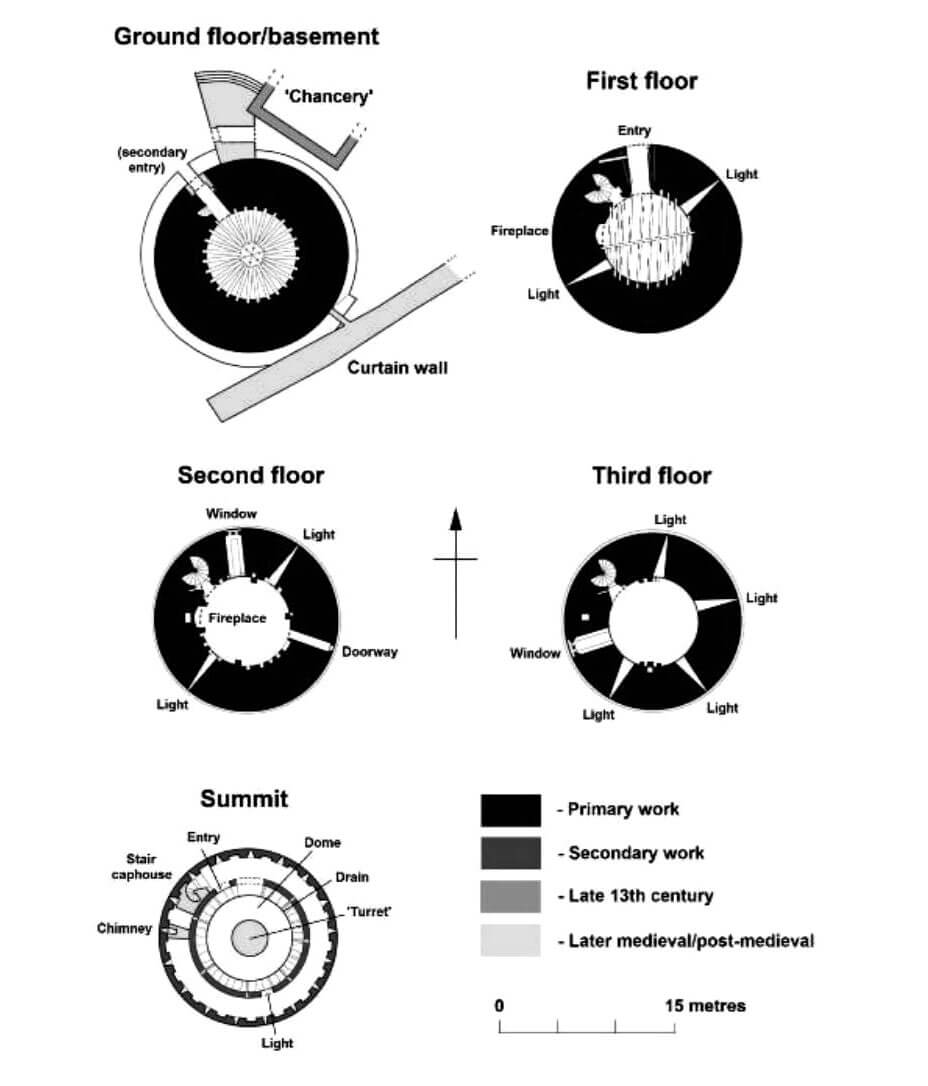

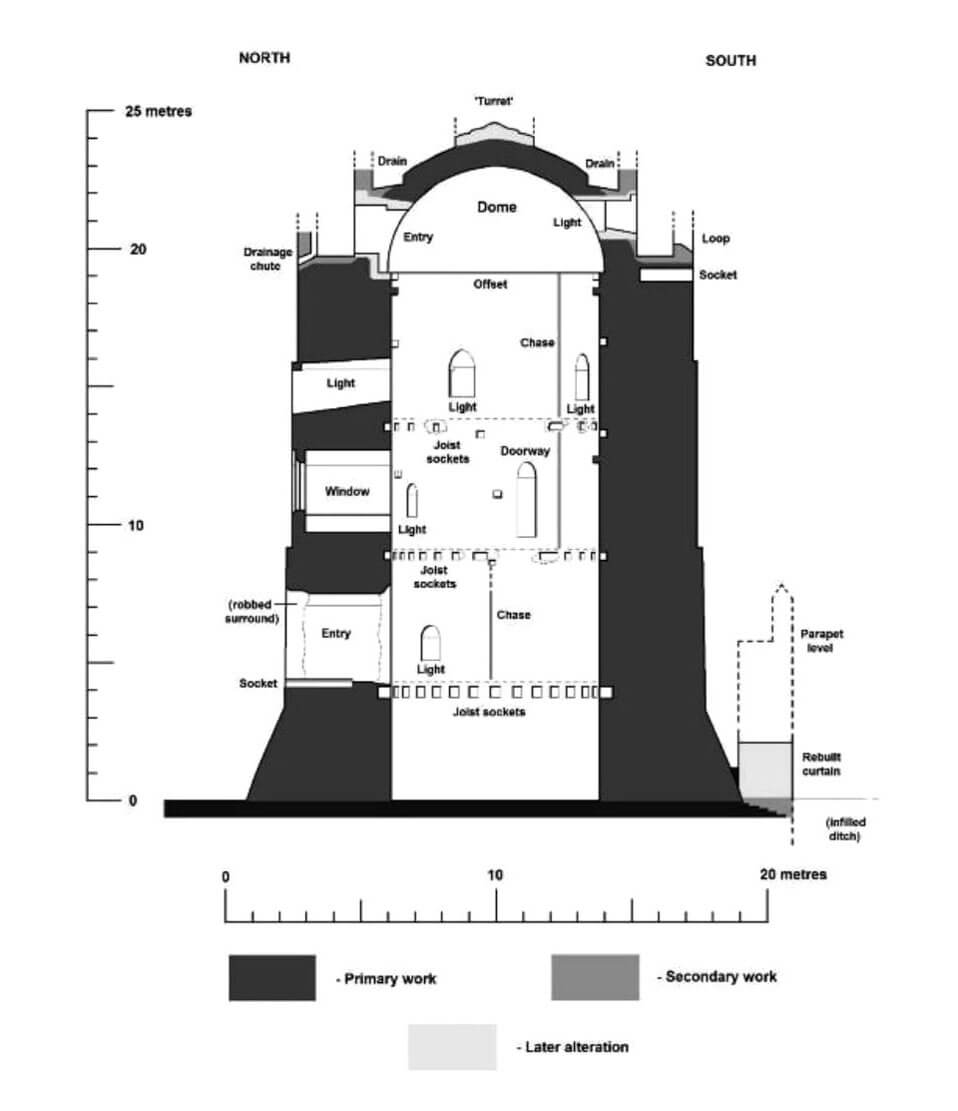

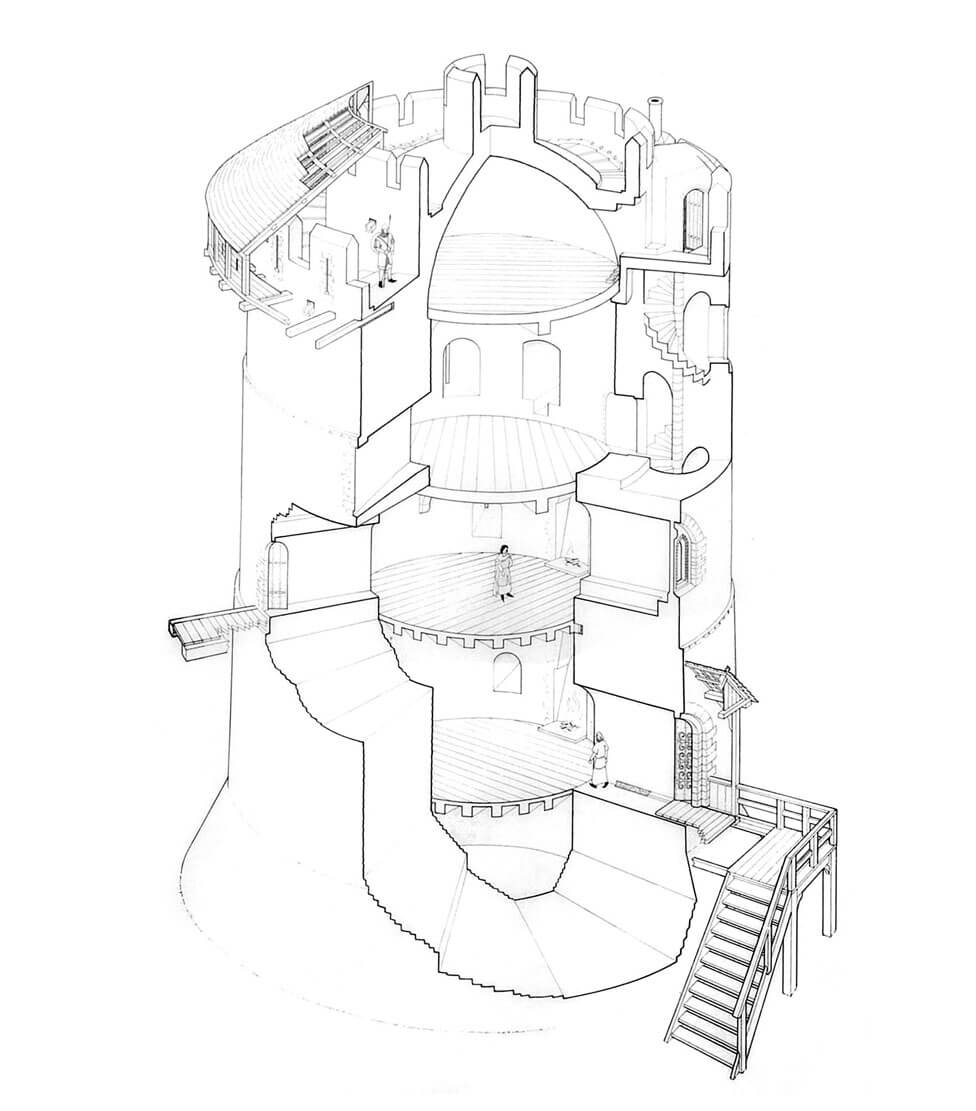

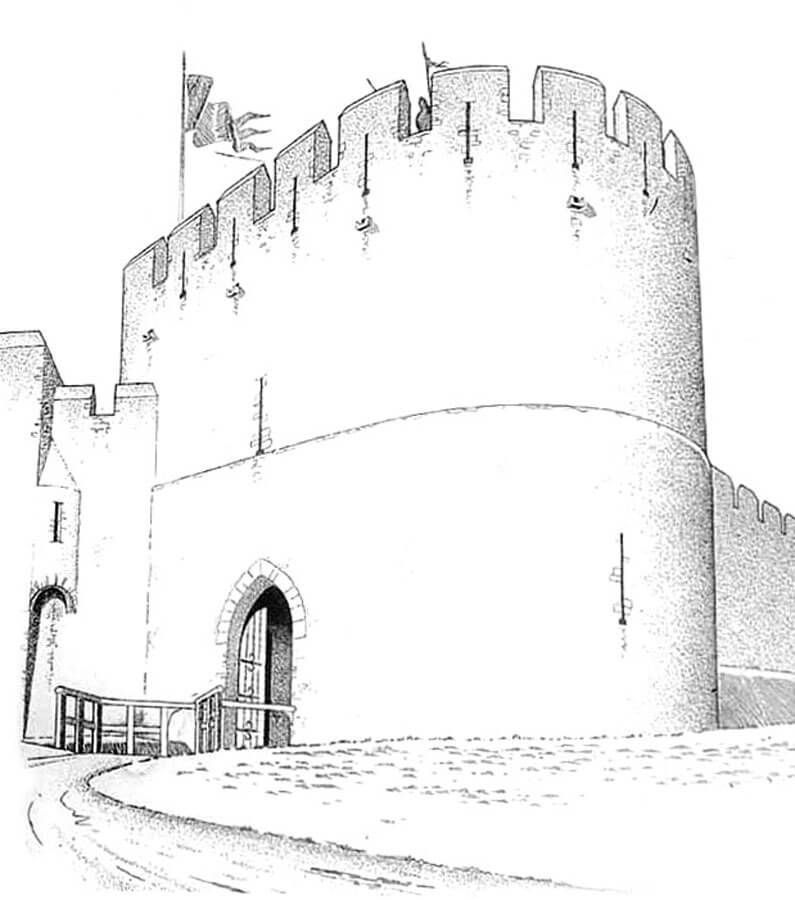

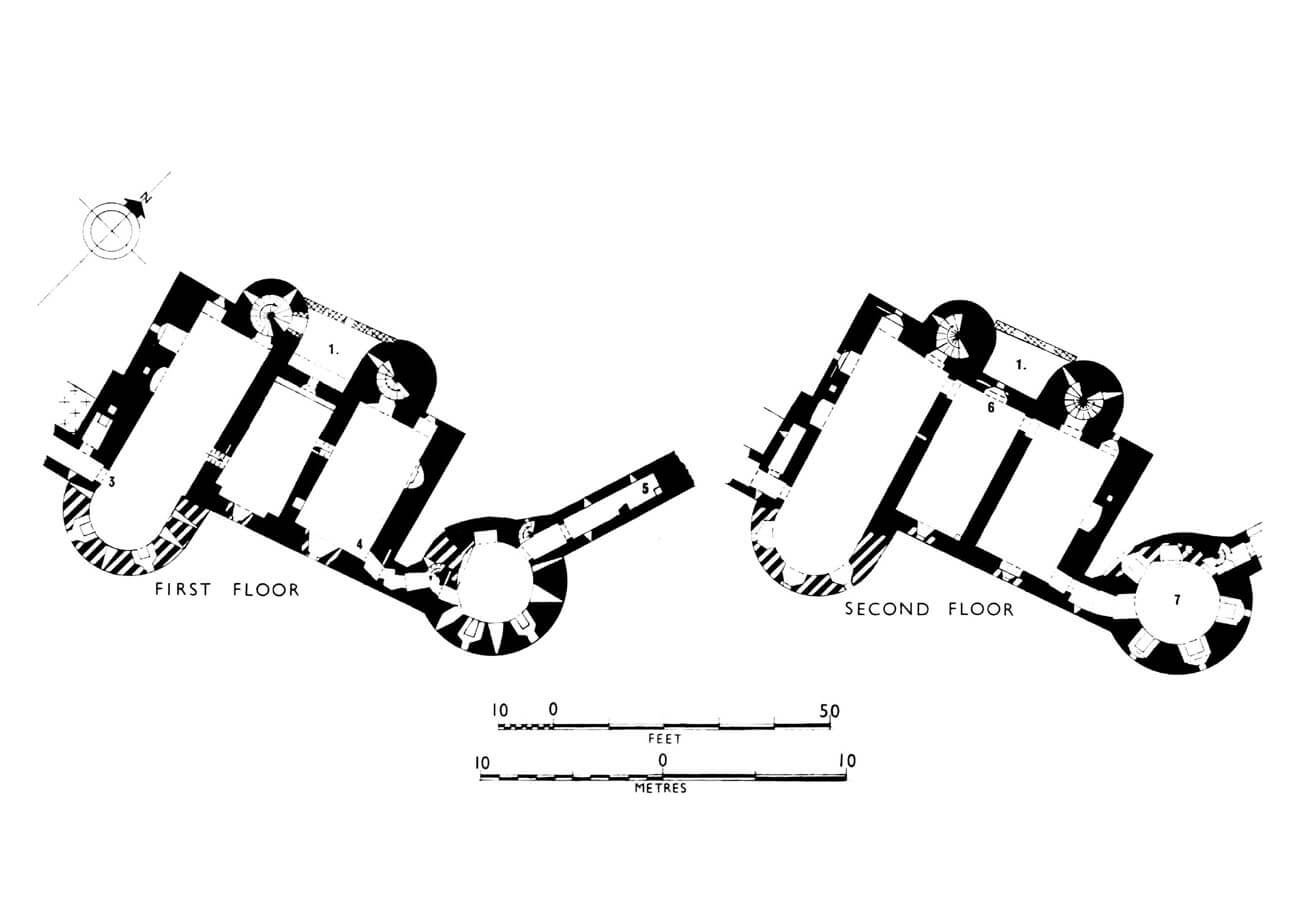

Around 1204-1210, stone elements began to be built on a larger scale at the castle. First of all, a massive cylindrical keep was built, one of the oldest and most magnificent to be built in Wales. It was probably inspired by similar structures from the Anjou area, which William could have encountered during his battles on the continent. It was erected on the highest point of the hill. Being almost 25 meters high it dominated the entire surroundings, and especially the ditch separating the castle promontory from the rest of the area. Its external diameter was 16 meters, and the thickness of the walls at the base was as much as 6 meters, where it were widened by a prominent plinth with sloping external elevations. The external elevations above were separated by two offsets topped with chamfered stones. The top floor of the tower was crowned by a stone dome with a watchtower mounted on it and two circuits of the parapet with battlements: a lower external one and a higher internal one. The holes visible in the wall would indicate that the upper part of the keep also had hoardings surrounding the outer parapet. Smaller holes in the parapet probably drained rainwater from the wall-walk. The fact that the hoarding was not a permanent element of the tower’s equipment is evidenced by the loop holes pierced through the merlons of the outer parapet.

The interior of the keep originally had four storeys separated by flat ceilings, with an entrance from the north at the height of the second storey, accessible via external wooden stairs. It could be blocked with a bar set in an opening in the wall, while the stairs themselves could be dismantled in the event of a threat. At the level of the third storey, there was a second, very narrow and high entrance, from which it was possible to get to the adjacent wall by a footbridge. This would have been a wooden connection, which could be removed at any time to prevent the keep from being captured by enemies. However, the wall-walk of the curtain was located as much as four meters below the threshold of the entrance, which would have required a complicated construction connecting the two parts, and the door in the entrance on the third storey of the keep was not blocked by a bar. It is therefore more likely that the portal led to a balcony, placed in the most exposed place, originally (before the expansion of the castle) facing the main street of the town and the probable site of the early market.

The third and fourth storeys of the keep were lit from the north and west by two early Gothic biforas, the openings of which were quite narrow and did not provide much light. From the outside, two lancet-shaped openings in both biforas were framed by a pointed recess with a carved mask under the boss of the archivolt (a motif similar to that used in William Marshal’s keep in Chambois). The frames of the openings were chamfered and decorated with a dog-tooth ornament. Inside, stone side seats were placed in the window niches, while in the central pillars between the openings, specially formed bulges were pierced with sockets for the shutter bar. The remaining openings in the keep were in the form of very simple slits. Although at first glance it seemed to be embrasures, it were mainly intended for lighting and ventilation. It had no transverse slits and were very poorly splayed in the interior, practically preventing archers or crossbowmen from conducting effective fire. Active defense of the keep must have focused on the upper surrounding galleries, while the openings themselves, in addition to the functions mentioned above, probably played a symbolic, perhaps deterrent role.

The communication between the entrance floor of the keep and the unlit ground floor and the upper floors was provided by spiral stairs embedded in the thickness of the wall. The two highest floors could be barricaded at the exit from the staircase with bars. This protection was not provided only at the utility ground floor level, probably used for storing wine. The ceiling there consisted of a system of twenty-eight radially arranged beams, probably supported by a wooden pillar. On the upper floor, the ceiling was already made of parallel beams, supported by one massive crossbeam, not set entirely at a right angle. The second and third floors were heated by fireplaces, which were very high, with segmental heads about 3.5 meters above the floor level. The second floor must have played the role of a warm vestibule, because there were only two slit openings in its wall. On the third floor, in addition to the two slits, lighting was provided by the early Gothic biforas mentioned above. A similar window and as many as four slits were pierced in the wall of the fourth floor, but its use had to be limited to the warm seasons due to the lack of a fireplace. Initially, the chamber could have been opened to the dome decorated with a painting, but later an additional ceiling was added to separate the low storage space of the attic. Despite the decorativeness of the windows, there were no latrines on any of the floors, and the openings were mostly in the form of very narrow slits, so the living conditions in the keep must have been quite harsh for a residence of the highest social class.

In the later Middle Ages, it was probably wanted to separate smaller and more private living spaces in the keep, which is why wooden partition walls were set in primitively cut grooves in the plaster on all three upper levels. It is possible that it was then that the ceiling for the highest floor was added under the dome, for which, in addition to the offset of the perimeter wall, additional support was provided by a partition walls. In the 15th or early 16th century, when the defensive aspects of the tower were no longer of any importance, a curved stone stairs were built leading to the entrance on the first floor. It was probably also then that a separate entrance to the keep was made at ground level to facilitate communication.

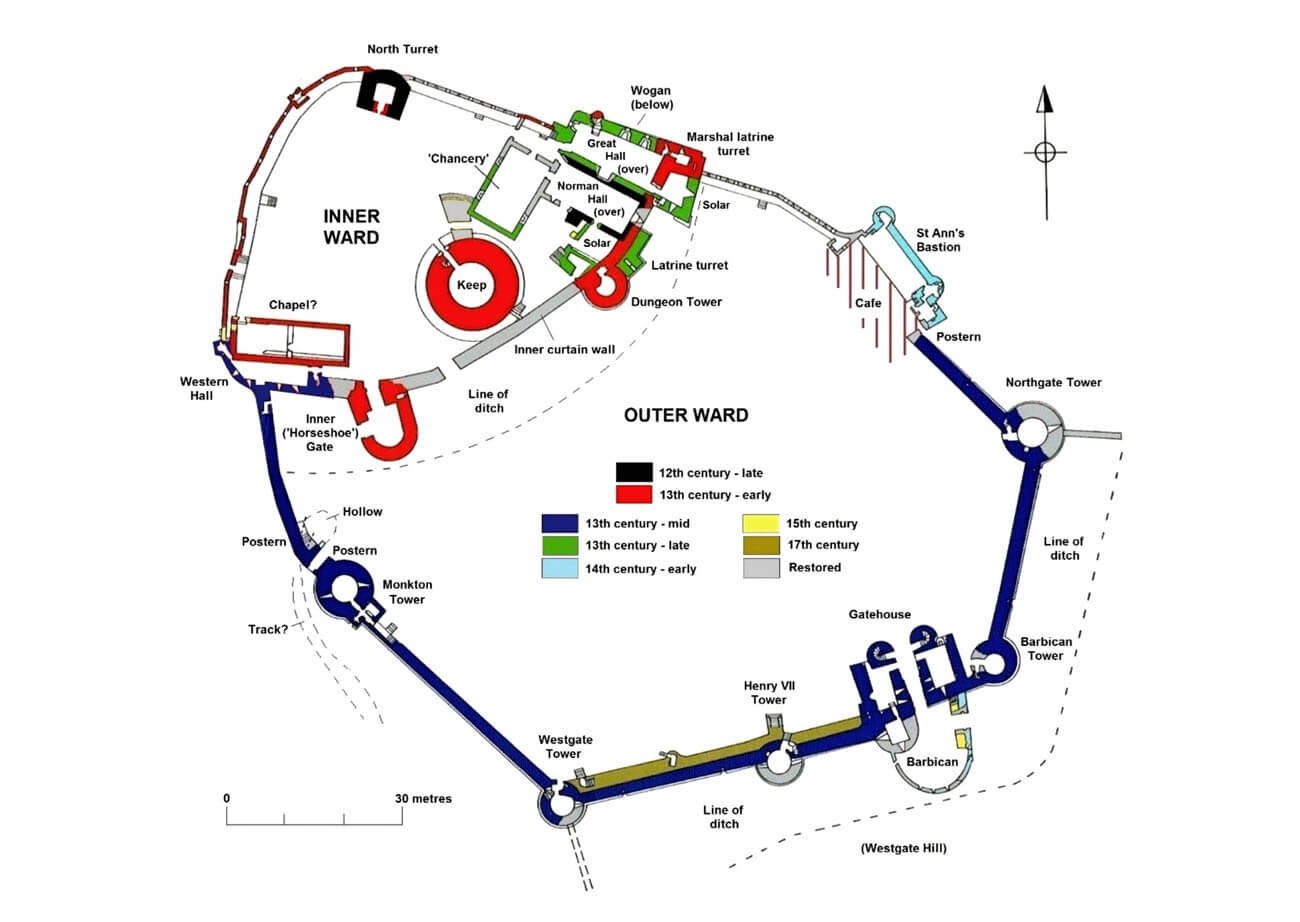

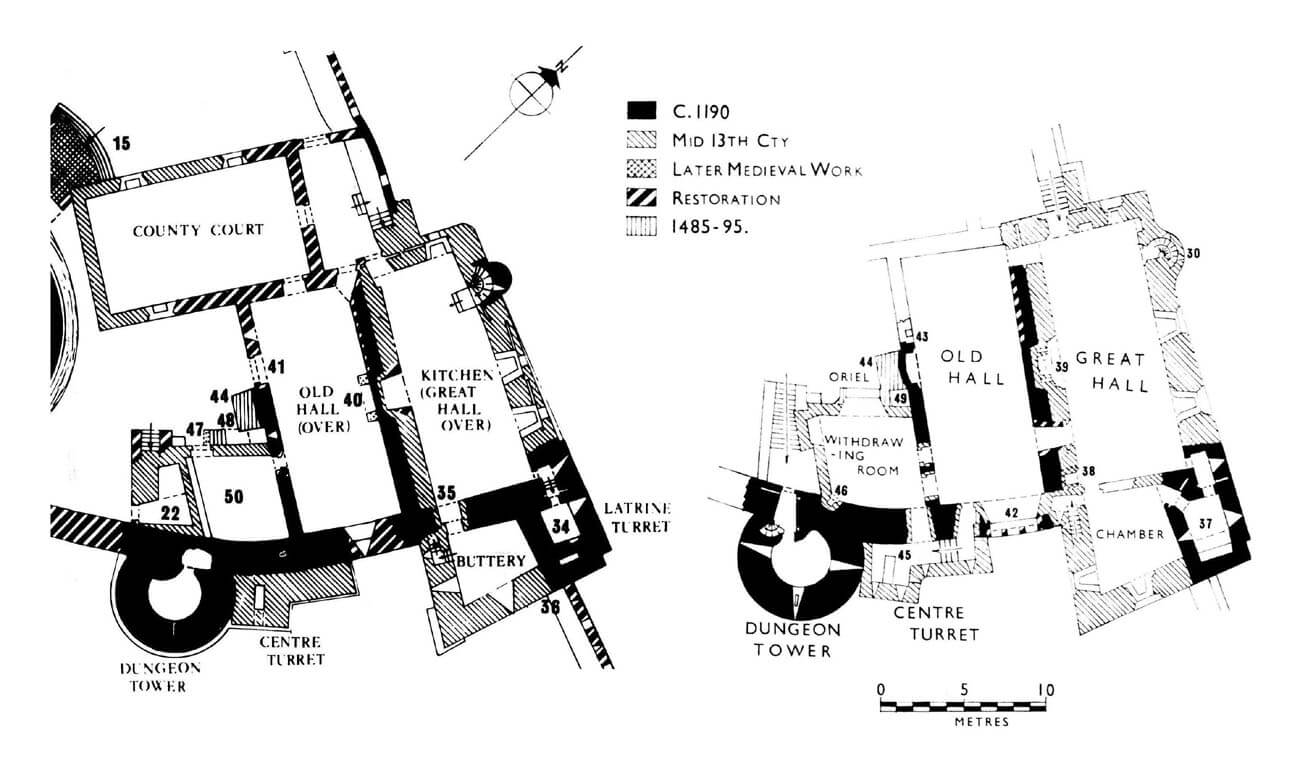

The defensive wall of the 13th century castle, the later upper ward, closed off an inner courtyard with a plan similar to a triangle. Pembroke was so well protected by natural conditions of the terrain that on the north and west sides the wall, although quite thick, had a wall-walk at a height of only less than 1 metre above the courtyard. In the front southern part the wall reached about 7.2 metres high to the level of the wall-walk and 9.2 metres in total height. In this section it was reinforced since the mid-13th century by the Dungeon Tower, in the east by a small corner Latrine Tower, a quadrangular northern tower and a small square turret (Point Tower) located to the west of it, acting as a latrine and observation point. The towers on the north side, as this was the direction best protected by terrain (high escarpment, body of water), did not have to be of considerable size. Similarly, the small Latrine Tower was more important for its function, from which it was named, than for its defensive properties. Only the quadrangular northern tower, which could have been one of the oldest stone buildings in the castle, erected in the 12th century, stood out with its massive walls.

The entrance to the castle was from the south, through a horseshoe-shaped, tower-like gatehouse, completely protruding in front of the neighbouring curtains towards the ditch. It was as much as 13.7 metres long, 9.1 metres wide and had a wall 2.1 metres thick at the front. The passage was located on its western side and had no portcullis, only double-winged door. After crossing the bridge over the moat, one turned sharply to the right, and inside the tower to the left, where there were another door leading to the upper ward. The gatehouse was most likely two-storey with a guard’s room on the upper floor, above the gate passage. Right next to it was a small latrine projection in the form of an overhanging turret, later partially absorbed by residential building. In the eastern wall of the gatehouse there was a narrow postern, allowing access to the base of the defensive wall, to the narrow area between the curtain and the ditch.

The Prison Tower was built on a horseshoe plan protruding about 11 meters in front of the curtain wall and about 9 meters wide. Inside, it had a circular cell on the ground floor, lit only by a single slit opening pierced in the eastern wall. Access to it was only through a hatch in the floor of the upper room, set about 3 meters above ground level. The first floor was the entrance floor, accessible by external wooden stairs, later stone one. A cylindrical staircase placed in the thickness of the wall led from the first to the second floor, vaulted with a dome. This floor was connected by a passage with a walk in the crown of the wall, while the tower, like all the others, was crowned by a unroof gallery hidden behind a battlemented parapet. Both floors of the tower were combat floors, each with three alternatingly placed arrowslits. All the arrowslits were much more effective than those used in the keep, with short transverse slits next to long vertical slits and oillets at the base. A quadrangular latrine block was added to the Prison Tower from the north-east at the end of the 13th century. It housed a latrine for the nearby 12th-century hall (which by then had already served as a private chamber) and a two-seat latrine for the nearby residential building (solar).

The residential and economic buildings of the upper ward were placed in its north-eastern corner. Initially, it was a rectangular building of the hall from 1150-1170 (Norman Hall). It is considered the oldest stone building in the castle, built even at the time when the fortifications were made of wood and earth. The entrance to it originally led straight to the first floor via external, wooden stairs. Inside the upper floor a fireplace was placed in the southern wall. It was the main residential and representative chamber in the castle until further residential buildings were built in the late 13th century. Then the 12th-century hall was transformed into a more private chamber or room for guests. The ground floor of the building served economic purposes as a warehouse or a pantry throughout the entire period of use.

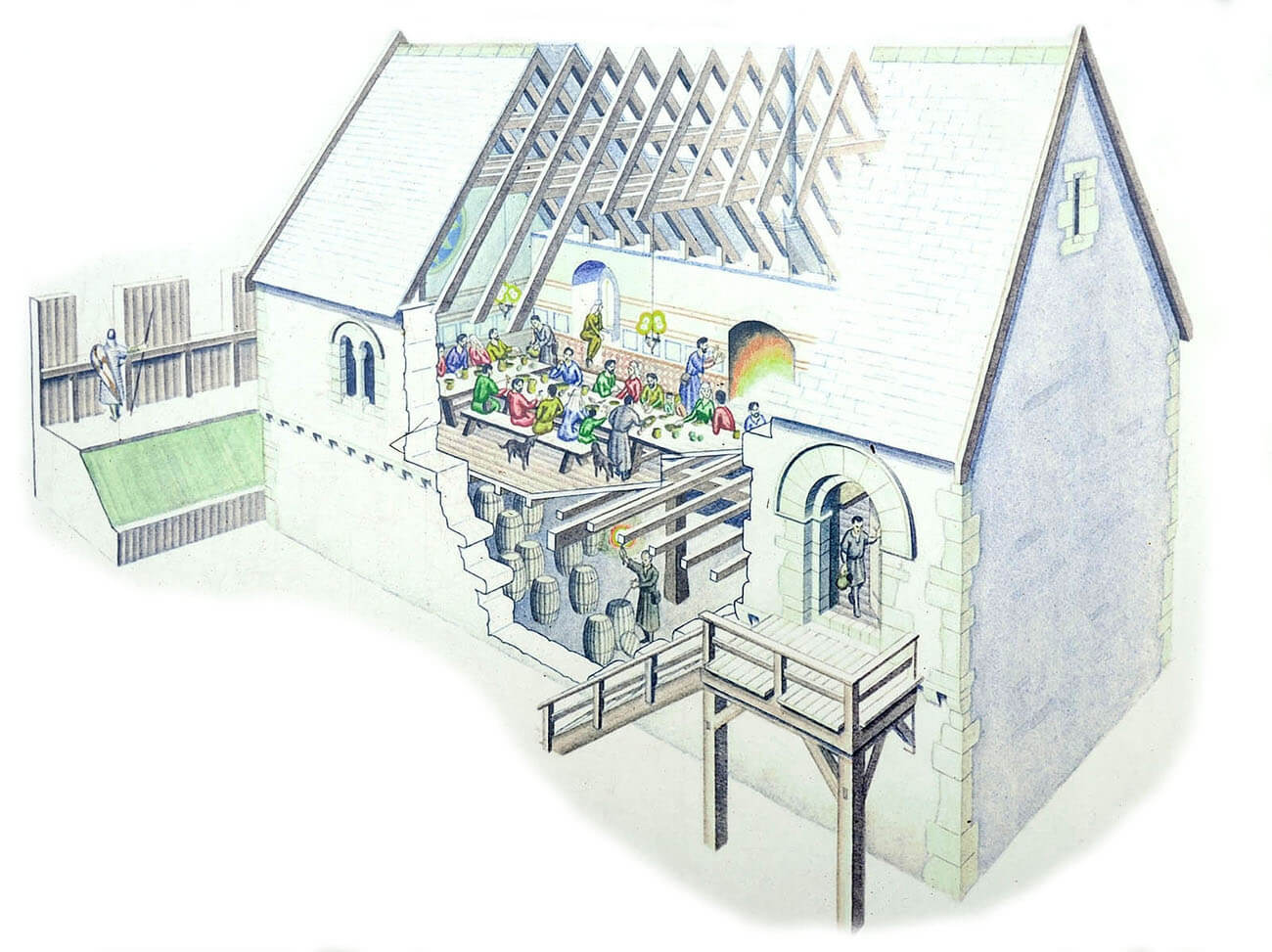

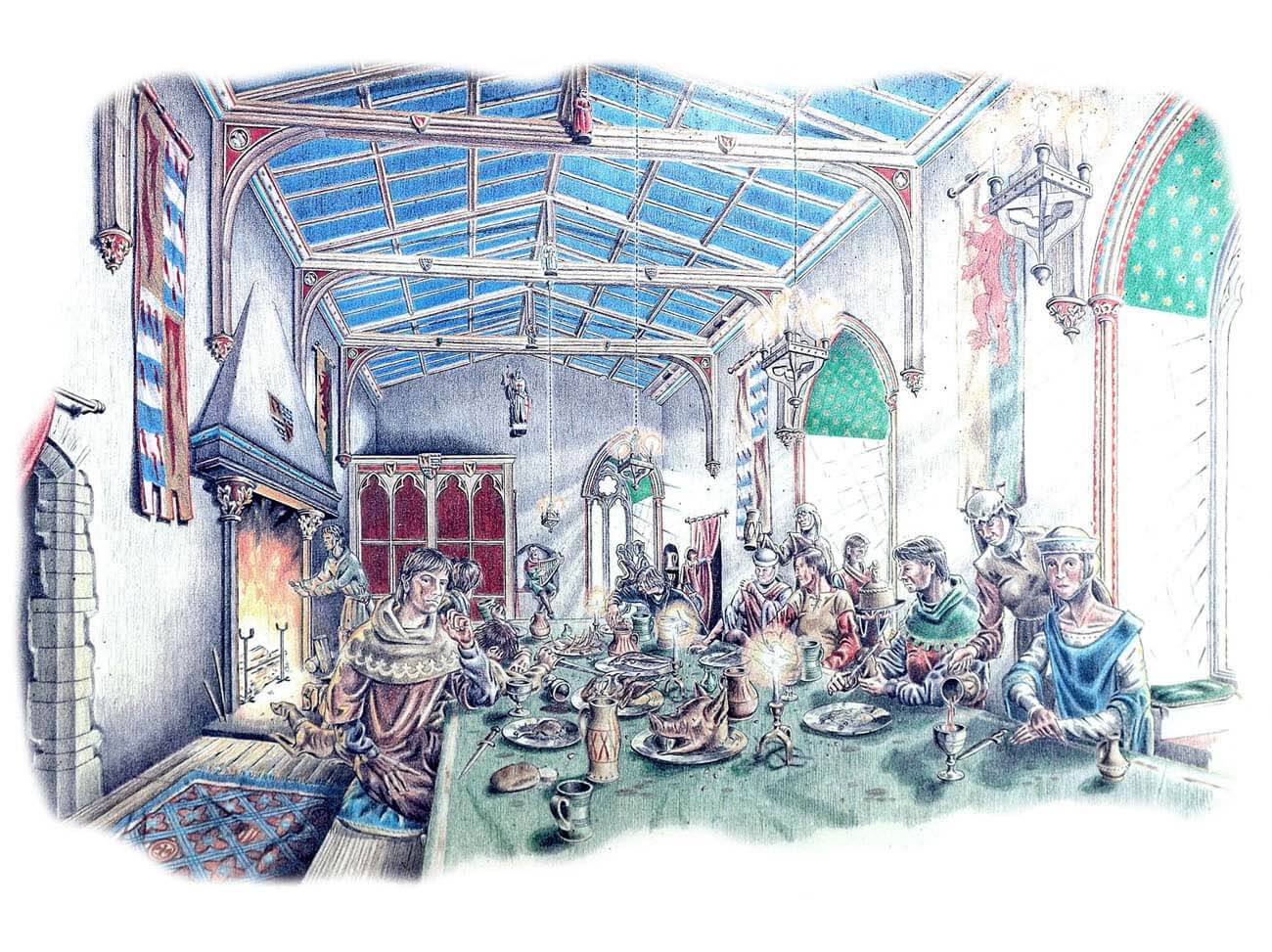

In the 1280s, an impressive great hall was added to the northern wall of the old hall, a two-storey tower-like building that absorbed the older corner Latrine Tower. The great hall building was topped with a parapet set on a row of corbels and four L-shaped corner turrets, each created on a successive row of consoles. On its ground floor was a kitchen with a large fireplace by the southern wall and two semicircular windows on the opposite side, both with stone seats and shutters blocked by bars. A third similar window was placed in the western wall, right next to the entrance. At the eastern corners there was a passage to the latrine in the former tower and a portal to a smaller room, probably a pantry. It was lit only by two slits, as it faced the castle foreground and then the courtyard of the outer ward. The great hall was located on the upper floor of the building. It was a place for hosting feasts and entertaining guests, the most representative room in the castle, lit from the river by large early Gothic windows with two-light tracery and side sedilia. The interior of the great hall was heated by a fireplace. In the western part, a screen separated the area for servants, waiting for instructions from the lord of the castle and making final preparations before bringing in the meals. Right next to it was an entrance from the outside, accessible by stone stairs. The great hall was also connected to the older building of the 12th-century hall, with a chamber in the former Latrine Tower and with an unheated chamber above the pantry, lit by two pointed windows, equipped with iron grates and side seats. Vertical communication was provided by the northern staircase protruding in a projection.

At the same time as the building of the great hall, a small residential building (solar) was also erected, added to the southern wall of the old hall and the eastern section of the defensive wall, where the curtain slightly bent before connecting with the Prison Tower. It had two storeys with single rooms on each. From the south, it were adjacent to the stairs of the Prison Tower, under which a small vaulted pantry was placed, but it were not directly connected. The building was topped with a fairly high gable roof, with one gable resting on the wall-walk and the other facing the courtyard. The room on the ground floor of the building was low and dark, ventilated only by two entrances and equipped only with a stone bench by the southern wall. The upper private residential chamber was heated by a fireplace with a chimney protruding towards the tower stairs. In addition, it was equipped with a small corner aumbry, originally closed with a door. Around 1480, solar received a late Gothic bay window on the courtyard side, supported by a solid pillar.

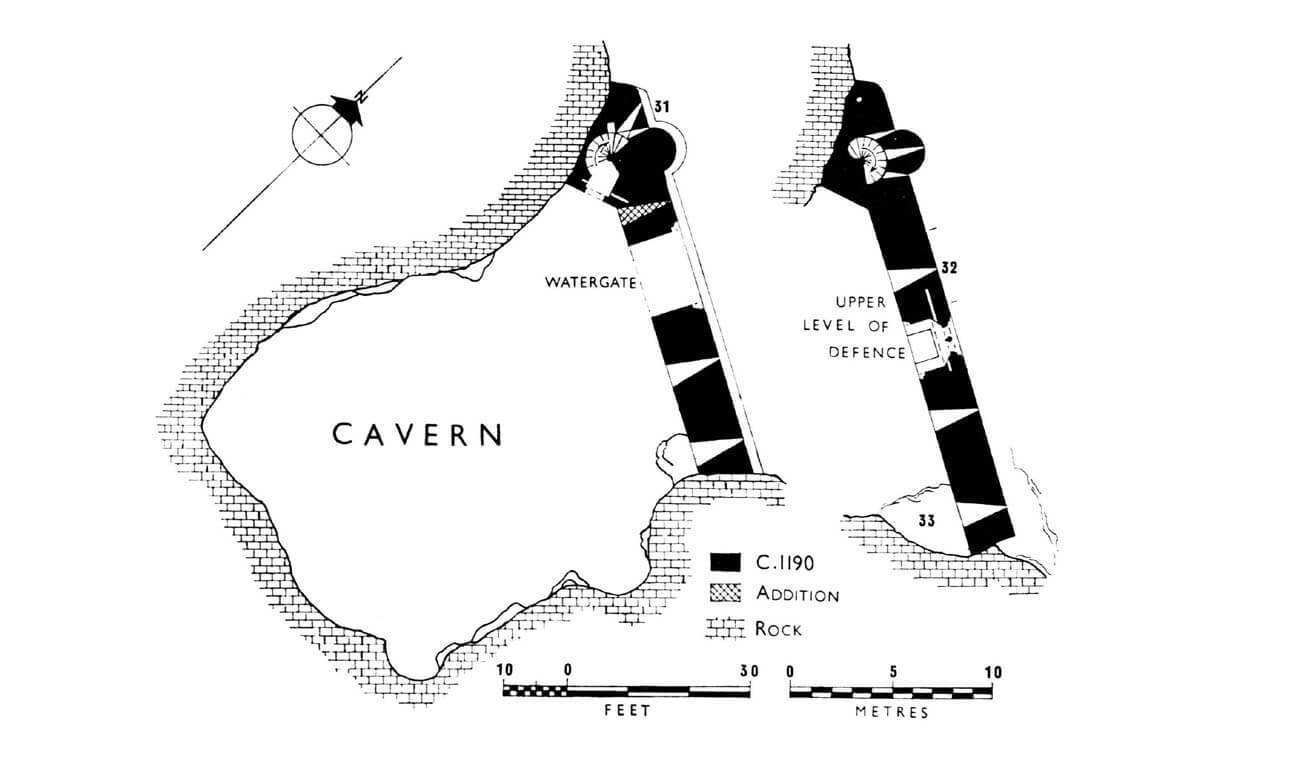

In the north-eastern corner of the upper ward there was a Water Gate, situated by the cave known as Wogan, lying under the building of the great hall and connected to it by a spiral staircase in the thickness of the northern wall. The bottom of the cave was about 4 meters above the level of the nearby stream. It was used already in prehistoric times, but during the Anglo-Norman time, it was closed with a massive wall 2.6 meters thick and intended for storage of food, drinks and boats. In the wall on two levels there were a total of six arrowslits, and further slits illuminated the above-mentioned staircase, set in the thickened north-western part of the wall. Interestingly, on the upper level of the wall there was also a large two-light window with sedilia, similar in form to the windows of the keep, but less decorative, closed with a shutter blocked with a bar. The exit from the stairs to the cave was closed with a door blocked by a bar set into a socket in the wall. The wide gate in the wall between the cave and the coast must have had some form of blocking. It was characterized by a threshold above the ground level in front of the cave (perhaps a wooden footbridge was added to the entrance).

At the end of the 13th century, a perpendicularly arranged courthouse (chancery) was built on the west side of the old hall building. All administrative and legal issues related to the earldom of Pembroke were resolved there. It was a rectangular, single-storey building, covered with a gable roof. It was lit by two large pointed windows on the west and one on the east, equipped with stone seats from the inside. The entrance led through the gable wall from the north, where a narrow, roofless vestibule was created in front of the defensive wall. In addition, the building was connected to the great hall by a portal in the east wall.

In the western part of the courtyard there was a rectangular building of the Western Hall, almost 14 meters long, which was placed against the inner elevation of the wall of the upper ward. It was a rather narrow building, with an irregular western end, single-storey, covered with a high pointed barrel vault, probably built by one of William Marshal’s sons between 1219 and 1245. Inside there was a latrine and a fireplace, with the latrine placed in a small projection set towards the riverside escarpments, accessible by a passage in the thickness of the wall. The building was lit by two openings in the western wall. Two more loopholes were created in the southern wall, covering the access road to the gatehouse. Next to the western hall there was a chapel, probably built on the site of an older, still wooden sacral building. The entrance to the chapel was originally from the west, but in the later Middle Ages it was bricked up and a new portal was made from the north. Also at a slightly later stage the chapel was partitioned by a transverse wall, perhaps built on the site of an earlier division into nave and chancel.

The outer ward stretched along the south-eastern side of the upper ward and covered the lower part of the rocky promontory. The beginnings of its fortifications date back to the years 1204-1245, but the stone defensive walls, about 1.8-2.5 meters thick and about 10-12 meters high, as well as five cylindrical towers were erected in the 1260s. In the 14th century, it were additionally reinforced from the north-east with the so-called St. Anne’s Bastion. In the Middle Ages, the spacious courtyard was occupied by numerous residential, economic and auxiliary buildings, mostly of wooden or half-timbered construction. Additionally, in the 15th century, a large stone manor house was built near the gate.

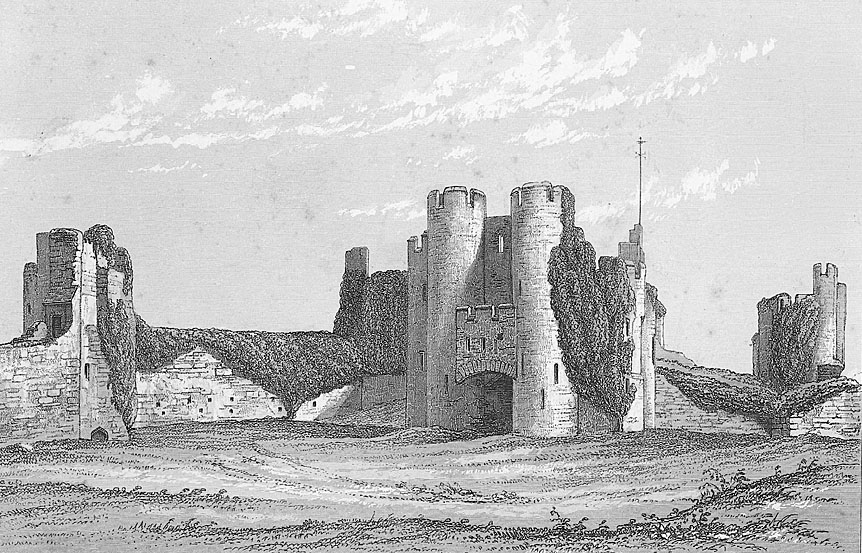

The entrance to the outer ward was located in the south-eastern, three-storey gatehouse. It had an unusual form, because the western part was a tower in the shape of an elongated letter D, and the eastern part was just a simple, quadrangular block. On the external side, additional protection was provided by a ditch carved in the rock, moved when the semicircular barbican was built at the beginning of the 14th century. The internal part (from the courtyard side) had two cylindrical communication turrets. The gate passage, like other contemporary ones, was defended by two portcullises, doors blocked with bars, two pairs of arrowslits and machicolations. On the sides were rooms for guards, of which the western one was heated by a fireplace and both were accessible from the gateway. Another two passages in the rear part of the gate led to spiral staircases in the rear turrets, one storey higher than the core of the building. Between them, at the first floor level, a segmental arcade was built, supporting a storey with loopholes and an opened gallery hidden behind battlement. The purpose of this structure was probably to strengthen the defence of the gate complex from the courtyard side and to make it an independent defensive work. Above the ground floor, there were three rooms of different sizes on each of the two floors of the gatehouse. The two outermost chambers served as living quarters for the castle constable and his family, as it were heated by fireplaces and well-lit, not only by loopholes, but also by windows with stone seats. In addition, the western rooms had access to latrines, set in the thickest part of the gatehouse wall. The middle room, slightly higher up on the first floor, housed the mechanisms for operating the portcullis. The middle room on the second floor could have had an auxiliary function, due to the lack of heating and only two windows. It differed from the lower room in the different arrangement of entrances, which no longer had to have steps to equalise the levels between the chambers. Each of the two floors was connected with corridors in the thickness of the wall of the neighbouring curtain walls and with walks crowning them, thanks to which it was possible to pass to the neighbouring towers.

To the east of the gate of the outer ward, the curtain wall was reinforced by the round Barbican Tower, and then the cylindrical Northgate Tower with a diameter of about 10 metres. From the early 14th century, the northern section of the outer ward was defended by a small, quadrangular Mill’s Bastion, together with the so-called St. Anne’s Bastion, at the base of which there was a postern. The section to the west of the main gate was defended by a wall reinforced with three towers. These were, in order, the cylindrical Henry VII Tower, the cylindrical corner tower called Westgate Tower, both about 7-7.5 metres in diameter, and the slightly larger Monkton Tower, 10 metres in diameter, built near the upper ward. The Westgate Tower and the Northgate Tower protected the corners of the castle and were connected to the curtain walls of the city defences.

Monkton Tower stood out from the other towers of the castle for its slightly larger size and two quadrangular tower annexes flanking the cylindrical core. One of the annexes had a postern on the ground floor leading to Monkton Bridge, situated next to an older, bricked-up gate that had operated before the tower was built. The interior of Monkton Tower also did not follow the pattern of the other towers, as it contained only two storeys that were not connected to each other. The lower level was entered from a lowered section of the curtain wall-walk on the south-eastern side, through a side annex that housed a latrine chamber and a small, dark room with an aumbry and a single opening facing the courtyard. Both the passage and chambers were vaulted. At the end of the passage, a barred door secured the entrance to the circular ground floor of the tower, located as much as 1.5 metres above the level of the courtyard. Its interior was lit only by two slits splayed towards the interior. The upper storey was accessible only from the wall-walk on the other side of the tower. It housed a smaller quadrangular chamber in the annex and a circular living room in the main part, equipped with a fireplace, two windows with seats and a loophole facing the front of the upper ward gate.

All three cylindrical southern towers had a similar form and dimensions. Each was three-storey, with fireplaces on the two upper floors and latrines. The floors were mostly separated by ceilings, but some rooms were vaulted (e.g. the second floor of Henry VII Tower). These elements would indicate that the southern towers, in addition to their defensive function, also served a residential role, although of not very high status, due to the poor lighting of the interiors. The two towers on the west side of the gate and the gate complex itself were connected by a long passage set in the thickness of the curtain wall on the first floor and reaching the second floor at the Westgate Tower. According to the original plans, there were to be latrines in the passage, but while the curtains were still being built, it were abandoned in favor of latrines placed only in the towers. The passage was primarily intended to facilitate quick movement between the towers under the protection of the walls and without having to go out into the courtyard. It was lit by regularly placed rectangular slits, which did not really serve as loopholes, due to the internal niches and embrasures being too small.

The Mill Tower was a quadrangular structure in plan, adjacent to a semicircular, higher projection. It was part of the so-called St. Anne’s Bastion, a fragment of the fortifications protruding towards the river on a massive outcrop. Its second, north-western corner had another rounded, but lower turret. The interior of the bastion from the courtyard side in the Middle Ages could have been occupied by a rectangular, single-storey building, next to which, in the bend of the wall between the Mill Tower and the southern curtain, there was the aforementioned postern. Its use could not have been easy, because it led to a path leading up a steep and high slope, but it significantly shortened the way to the waterfront.

Current state

The Pembroke Castle is currently one of the best preserved strongholds in Wales. It survived and was restored the entire circuit of the defensive walls with the towers of both the upper and lower ward (inner and outer ward). Of particular interest must be one of the oldest and best preserved donjons in Great Britain, surviving in almost its full height, but with a reconstructed staircase and without the original entrance portal. Of the elements that have not survived to the present day, the most striking is the lack of the horseshoe gate tower, the adjacent fragment of the upper ward wall and the filled-in ditch. The reconstructed parts are significant fragments of the towers at the gate of the outer ward, as well as its foregate (barbican) and sections of the defensive wall in the northern part of the complex. In the early modern period, the southern section of the wall between the gatehouse and the Westgate Tower was significantly thickened. The castle is open to visitors throughout the year, from April 1 to September 30 from 9:30 to 18:00 in March and October from 10.00 to 17.00, on Saturdays from 10.00 to 16.00.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

King D.J.C., Pembroke Castle, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 127/1978.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Ludlow N., Pembroke castle. Birthplace of the Tudor dynasty, Pembroke 2001.

Ludlow N., William Marshal, Pembroke Castle and Angevin design, “The Castle Studies Group”, No. 32/2018-2019.

Renn D.F., The donjon at Pembroke Castle, ” Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society”, 15/1968.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.