History

The castle or manor in Oxwich was built in the 16th century, on the site of an earlier building belonging to the Penrice family, which in 1459, under the name “castrum de Oxenwych”, fell into the possession of Philip Mansel (Mauncell) as a result of marital affinity. The Mensels temporarily lost their fortunes during the Wars of the Roses, when they supported the Lancasters, but returned to favor during the reign of Henry VII, probably in recognition of their services during the march on Shrewsbury and Bosworth. Philip’s son, Rice (Rhys) Mansel, a talented soldier and administrator, was the first in the family to achieve more than local importance, become closely associated with the royal court, and also inherited the estates of the Basset family from Beaupre, thanks to which was able to undertake a thorough reconstruction in Oxwich.

The first stage of construction works on the new Oxwich buildings began around 1520 at the earliest, and was probably completed in 1538, when Rice Mansel leased the dissolved Cistercian abbey in Margam. It focused on providing a comfortable place to live, although Oxwich’s isolated location also required the construction of light fortifications. This was probably also influenced by the so-called “Oxwich Affray“, a skirmish between Sir Rhys Mansel and Sir George Herbert, fighting at the end of 1557 for the right to the cargo of a wrecked French ship.

Rhys Mansel died in 1559, long before the new castle was completed, but the work was continued by his son, Sir Edward Mansel, and his wife, Jane Somerset, daughter of Henry, second Earl of Worcester. However, Oxwich did not satisfy the ambitions of the family, which soon moved their main residence to Margam. The castle was leased and began to fall into neglect. By 1631, part of the eastern wing had collapsed and was never repaired, although the older southern wing continued to be used as a farm until the early 20th century.

Architecture

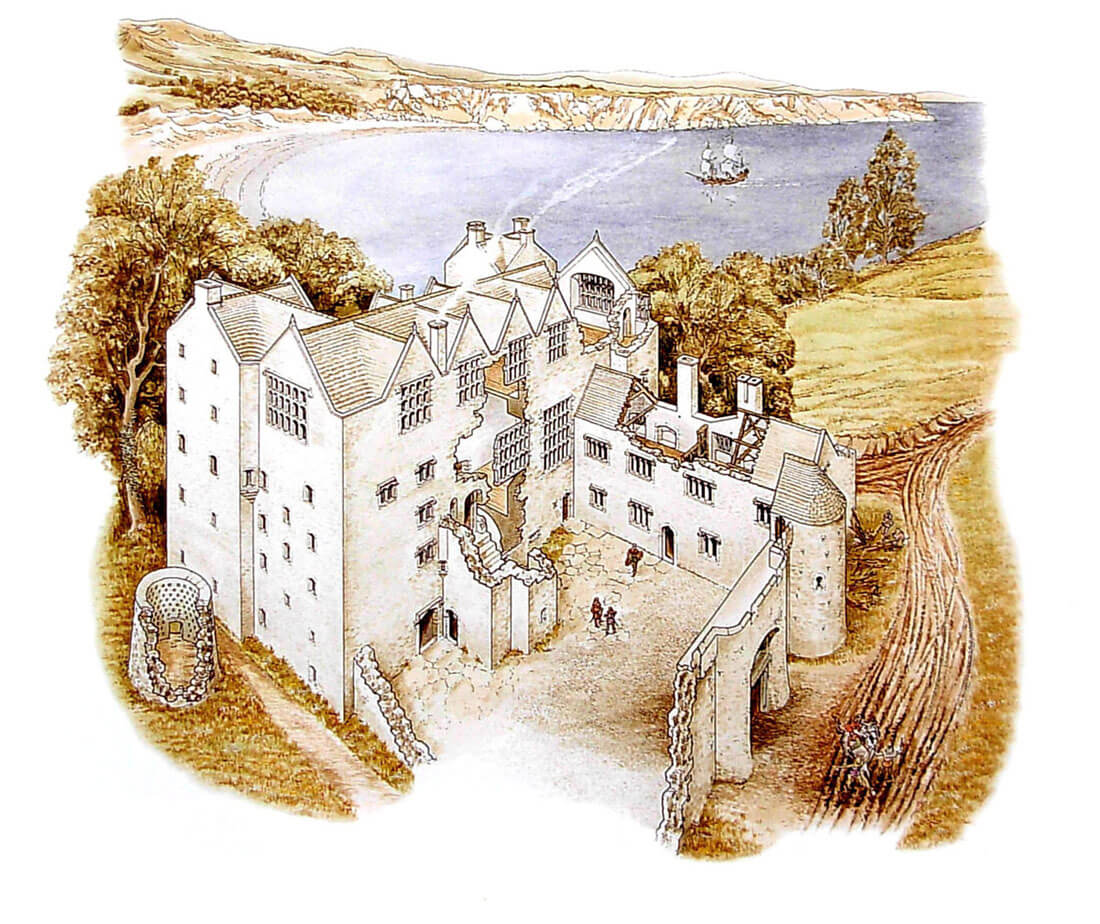

The castle was built on a wide promontory extending towards the waters of the Bristol Channel, characterized by high and rocky shores. It occupied north-western part of the promontory, protected from the north by steep slopes descending towards the Oxwich marshes. The access road must have led from the west, from where the headland joined the rest of the Gower Peninsula. In the south and east, the area of the headland, apart from the seaside shores, was devoid of any major natural obstacles.

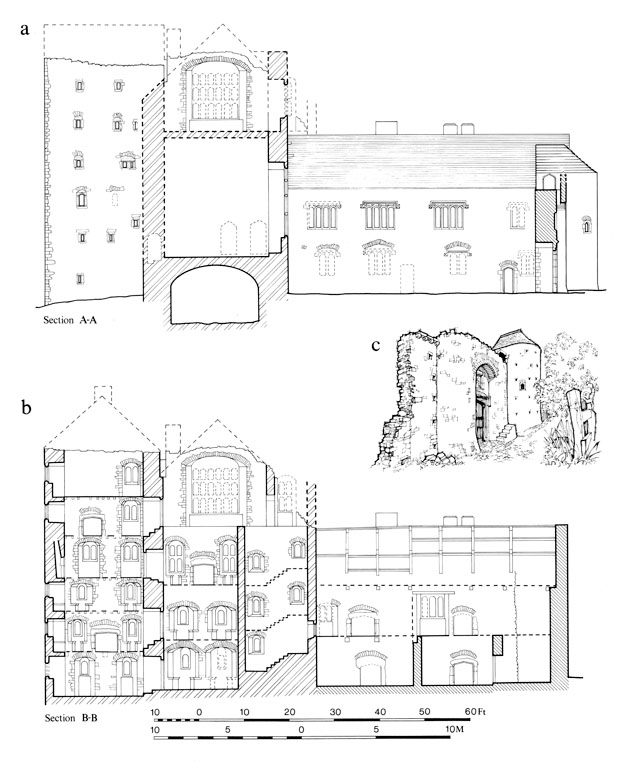

The oldest part of the 16th century castle was the southern range, erected in the first half of that century. It was a rectangular building with a small projection in the southern part, with two floors and an attic. In its eastern part, in the ground floor, there was a kitchen, equipped with a fireplace and a small stone oven in the wall. Further on was the central room heated by the fireplace and two small rooms in the corner, originally intended for servants. The upper floor was illuminated by large rectangular windows: one two-light and three four-light. Originally it was divided into two parts with a wooden partition screen and topped with a flat timber ceiling that separated the upper attic. Two rooms of the first floor functioned as the main chamber of the residence’s owner and as his bedroom, both heated by separate fireplaces. Communication between all floors was provided by a spiral staircase located in a horseshoe tower, accessible from the corner of the courtyard.

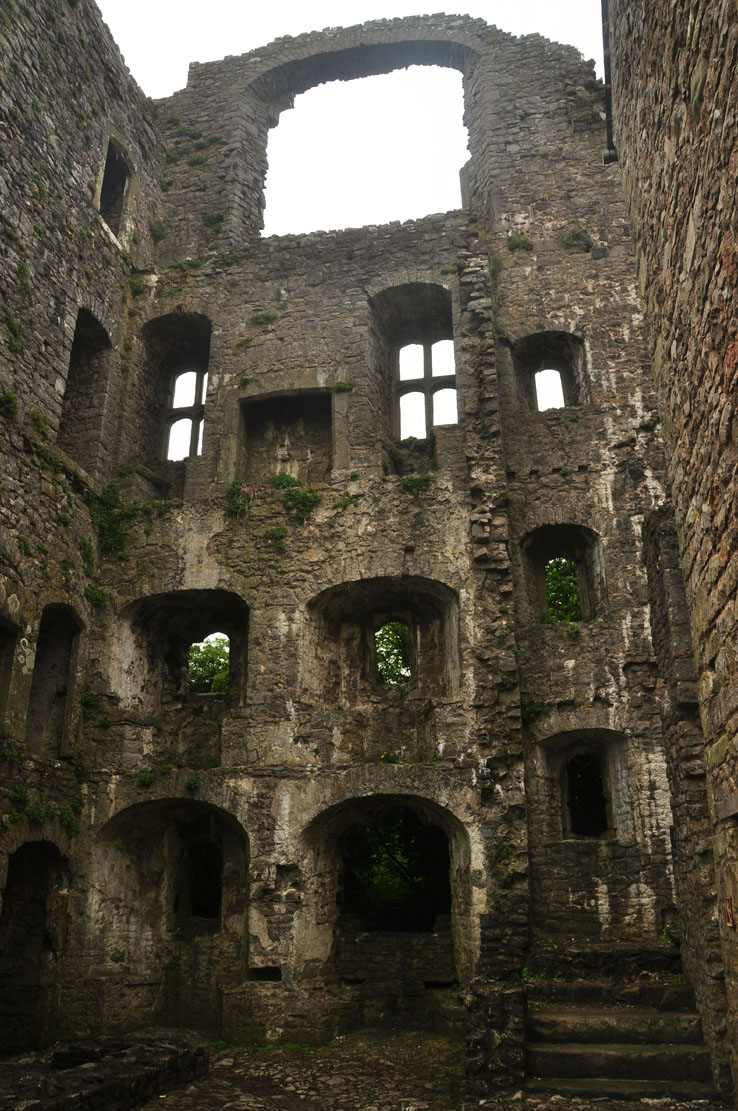

In the second half of the 16th century, an east range was erected consisting of a long, rectangular building with massive walls 2 meters thick, with three projections from the east and north of a tower-like character. All projections were four-sided, the middle slightly smaller than the other two. The entrance was from the courtyard side and led to the first floor, through the stairs in the vestibule. Behind the entrance portal was the centrally located, main room of the castle, that is a great hall with a plan size of 17 x 7 meters, rising to the level of the second floor. It was a place of meals, sumptuous feasts and meeting guests. Its lighting was provided by unusual huge windows consisting of three levels of smaller two-light openings in one case and four levels of openings in the other window. From the north and south, the hall was flanked by smaller rooms, while a fragment of the wall of an older, medieval building was used for the northern room. The space of the entire third floor was occupied by a long gallery, illuminated with windows similar to those used in the great hall, and communication was made possible by staircases located on the southern and northern sides. Their construction was based on a central stone pillars, around which straight sections of stairs were led. It was one of the oldest solutions of this type in residential buildings. The main building of the east range also had two barrel vaulted utility rooms and a couple of smaller rooms at ground level. Tower projections probably housed living quarters. The preserved south-eastern tower had six floors, each of which except the ground floor was heated by a fireplace and equipped with irregularly pierced windows. A latrine was probably placed in the corner niche.

The defensive devices of the castle were limited to the wall on the south-west side, which separated a small courtyard measuring 20 x 16 meters. It was reinforced by a horseshoe tower on the south side, which flanked the gate next to it, located between two twin small turrets. Above the passage, between the turrets, an arcade was stretched, hiding machicolation. Perhaps a second tower was also in the not preserved west corner of the castle. The defensive wall was topped with a parapet on slightly protruding corbels and a battlement, which protected the defenders’ wall-walk. Access to it was possible through the southern tower.

Current state

The castle has survived to modern times in a state of partial ruin. The southern range has been preserved in its entirety, although it has been rebuilt over the centuries. Among other, the attic was lowered and windows and door portals on the ground floor were transformed. Of the east range, the south and south-eastern walls and the south-eastern tower have been preserved to the full height, partly the north wall of the building has been survived, the remaining fragments have unfortunately collapsed. Visible is also the horseshoe tower and the castle gate, although the wall adjacent to it preserved only in the lower part. On the north side you can see the ruins of the dovecote. The castle is open to visitors from March 24 to November 4, from Wednesday to Sunday from 10.00 to 17.00.

bibliography:

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan The Greater Houses, Cardiff 1981.

Williams D., Gower. A Guide to Ancient and Historic Monuments of the Gower Peninsula, Cardiff 1998.