History

St Woolos’ Church in Newport was built in the first half of the 11th century, on the site of a chapel of around 5th or 6th century. According to tradition, the Welsh ruler of Gwynlliog’s cantref, Gwynllyw (name later corrupted to Woolos), built a penitential cell and chapel on Stow Hill. When he died in the early 6th century, he was buried near his church (“Eglwys Wynllyw”), which became a place of pilgrimage. This church was burned down in the 11th century by Caradoc ap Gruffydd of Caerleon and rebuilt, and then extensively reconstructed at the initiative of the Anglo-Norman conquerors of Wales. Between 1139 and 1146, Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury issued an indulgence for those who helped the church of St. Gundlea (St. Woolos) in Newport. Indulgences were usually associated with financing the construction works, which would indicate that a Romanesque church was under construction in Newport at that time. The completion of this work, or the second stage of construction, took place around 1156-1161, when another indulgence was issued.

Between 1093 and 1104, St Woolos’ Church was given by Robert de la Hay to St Peter’s Abbey in Gloucester. This led to a long dispute between the monks and the lords of Newport, the earls of Gloucester, between 1123 and 1156, for Robert, the first Earl of Gloucester, had already taken the church from the monks and installed his priest Picot in it. After Earl Robert’s death in 1147 and Henry II’s accession in 1154, Gloucester Abbey made a claim. Two years later, when the case was heard by Archbishop Theobald, Picot claimed possession of the church by “monastic right”, representing the canons before the Anglo-Norman invasion. The Archbishop ultimately ruled in favour of the abbey, prompting Picot to make the desperate and probably ineffective gesture of hiding the church’s keys.

The proximity of the castle of the lords of Newport to the church also encouraged conflict in the 12th century. For example, between 1186 and 1189 the Dean of Gloucester, the abbey’s clerk, claimed that since its foundation the castle chapel had owed services to the mother church of St. Woolos, who was to provide a priest to serve it. William de Bendengis, the constable of “Novo Burgo”, however, ignored tradition and apparently appointed a separate chaplain. The documents do not record how the dispute was settled in subsequent years.

In the early 15th century, St Woolos’ Church was destroyed during Owain Glyndŵr’s Welsh rebellion, when Newport was taken by rebels in 1403 and recaptured two years later. After the rebellion was quelled, the church was repaired and probably enlarged at the same time with new late Gothic aisles, wider than the old Romanesque aisles. Further building work was carried out on the church around the 1480s and 1490s, when the west tower was built, perhaps funded by Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke and uncle of King Henry VII. A southern porch was also added to the church in the 15th century.

In 1818-1819, the church was repaired, unfortunately in the process the form of the windows of the west chapel was changed and the tympanum from the west portal was destroyed. Then, in 1853-1854, the medieval porch was demolished and a new one was built in its place, the windows of the aisles were replaced by new ones and the roof covering was renewed. The chancel was also completely rebuilt at that time by the brothers Edward and William Habershon. In 1913, the architect William Davies built the sacristy, once again transformed the windows of the west chapel and also completed the renovation of the roofs. In the years 1960-1962, the 19th-century chancel was demolished in order to build a larger choir, necessary due to the establishment of the church as a cathedral in 1949.

Architecture

St. Woolos’ Church was built on the edge of a hill, bounded to the east and south by high slopes, descending towards the River Usk estuary. The original early medieval settlement developed on the hill around the church, which after the Anglo-Norman conquest was moved closer to the river, at the base of the hill and near the bridge. A castle was built to the north of the new town before the mid-14th century, replacing an older motte-type stronghold on the west side of St. Woolos’ Church. As a result, during the High Middle Ages, the main parish church of the town was unusually located outside its fortifications.

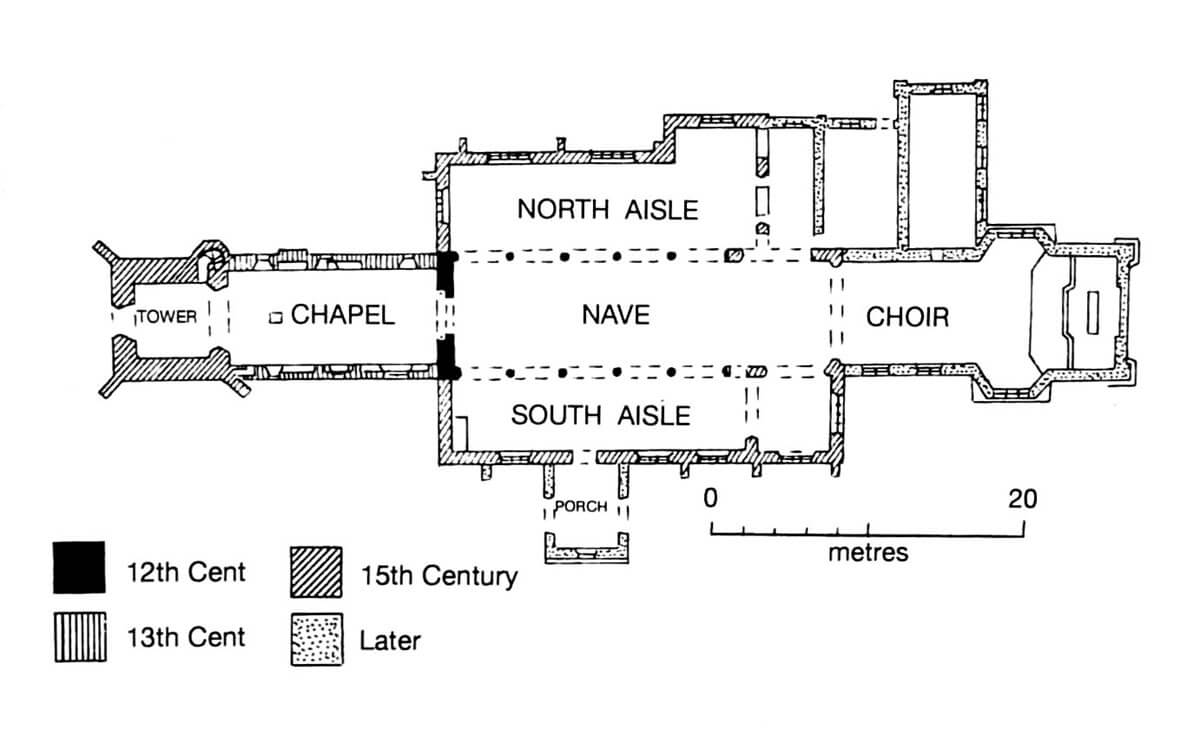

The Romanesque church from the mid-12th century consisted of a rectangular nave with two aisles, five bays long. It had the form of a basilica, so its wider central nave was lit by its own windows set in the clerestory. On the eastern side it ended with a chancel of unknown shape, while on the western side it must have been preceded by St Mary’s Chapel, raised and rebuilt in the early 13th century. Chapels at the façade were quite common in early Welsh churches. Their purpose may have been to house the tomb or chapel of the patron saint and to facilitate access for pilgrims.

Access to the Romanesque church was from the west, through a magnificent recessed portal with a semicircular closure, set in the wall of the nave. It never had a door installed, so it was not intended for the external part of the church, which would indicate that the chapel was in use before the construction of the nave. Single columns were inserted into the recesses of the portal on the sides, perhaps brought from the former legionary fortress of Caerleon, because of their sophisticated entasis and the integration of the bases with the shafts. The columns were supported an internal archivolt, while the external archivolts were placed on imposts. The columns were set on simple plinths and topped with capitals decorated with Corinthian leaves and Ionic volutes, with figures and birds hidden among plant motifs, representing the symbolism of resurrection and life after death. Usually on Romanesque capitals the faces were calml and the leaves symmetrical, indicating peace and order in heaven, but the sculptures on the Newport capitals were presented unusually, because the motifs were irregular and the figures attracted the eye with lively gesticulation and placement among the stars, thanks to which the simplest observer could imagine that he was entering the afterlife. The archivolts were decorated with four types of patterns and a motif of a semicircular, intersected shaft with evenly spaced elements. Originally the portal had also a tympanum, probably with a simple geometric pattern, carved or painted, with a recess cut out later.

Inside the church, semicircular arcades between the nave and aisles, moulded with simple offsets, were supported by two rows of massive, circular pillars. The pillars were equipped with circular bases, quadrangular plinths, capitals decorated with scallop motifs and moulded quadrangular abacuses. In contrast, the pairs of semi-pillars by the walls on the west and east sides were created quadrangular, with cut corners. The lighting of the central nave was provided by semicircular, splayed inward windows with ashlar frames of the niches, placed exactly on the archivolts of the arcades. A single window was also created on the west above the entrance portal. The narrow side aisles had to be lit by similar openings, perhaps slightly shorter due to the low height of the aisles. No part of the nave was covered with stone vaults.

Presumably in the 14th century the original Romanesque chancel of the church was rebuilt, either closed with a straight wall or finished with a semicircular apse. The Gothic chancel was built on a rectangular plan, reinforced in the eastern corners with buttresses set perpendicularly to each other. Towards the central nave and a short Gothic choir with a slightly greater width the chancel opened with an arcade, in front of which a rood screen was placed, with the first floor accessible by a spiral staircase in the thickness of the northern wall. The chancel was lit by large tracery windows in the style of English Perpendicular Gothic, in the southern wall two-light, in the eastern wall four-light.

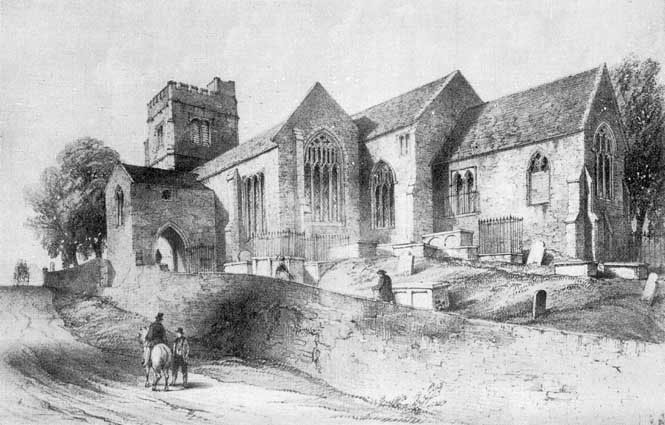

In the 15th century, the northern and southern aisles of the church were widened, with new walls and architectural details erected in the Gothic style, while the central nave remained in the Romanesque style. The Gothic aisles were created not only wider, but also higher than their Romanesque predecessors, which caused the church to lose its basilica form, as the separate gable roofs of the aisles covered the windows of the central nave in the longitudinal walls. Both aisles were reinforced from the outside with slender buttresses and lit with large pointed tracery windows. In addition, a two-storey porch was built in front of the entrance from the south, at the third bay from the west. Unusually, the entrance arcades were placed in it from the east and west, not in the southern gable wall. In the latter, a large pointed window with a multi-light tracery was inserted.

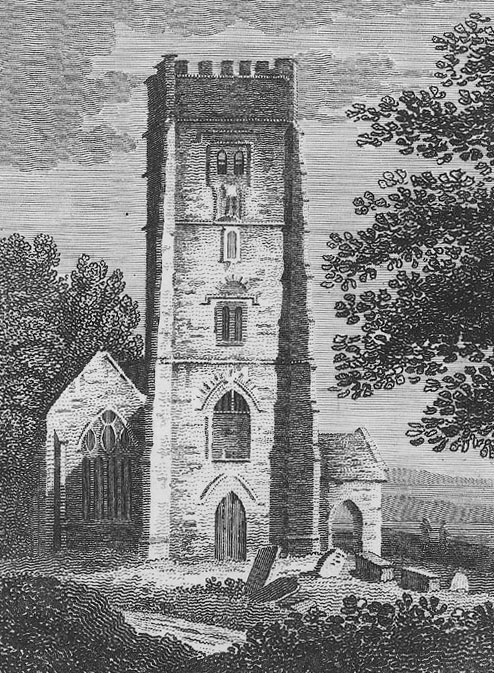

In the late 15th century, a quadrangular tower was built in front of the chapel’s western façade. It was reinforced by high, stepped buttresses at the corners and a north-eastern, polygonal turret with a spiral staircase. A double plinth cornice was placed on the ground floor of the tower, cut from the west by a pointed entrance portal to the church. The upper storeys were separated by two string cornices, and a decorative parapet with battlements was placed above the top floor. Lighting was provided by a large pointed western window with a three-light tracery and simpler two-light windows, between which a niche for a figure was placed on the western elevation, probably representing Jasper Tudor. Inside, the ground floor of the tower opened onto the chapel with a high and wide arcade with continuous moulding from the plinth to the of the archivolt.

Current state

The church has an unusual spatial layout today, as it is a combination of elements from many different eras. The oldest are Romanesque walls of the central nave, covered by later walls of the side aisles. St. Mary’s Chapel largely dates from the 13th century, although the lower parts of its walls may date back to the 12th century. The western tower (known as Jasper’s Tower) and aisles have late Gothic forms. The eastern part of the church ends with a chancel, the current shape of which is the result of a 19th-century reconstruction. The southern porch at the aisle has been so thoroughly rebuilt that it is essentially a 19th-century structure.

All of the windows of the aisles and chancel were transformed in the Victorian period and at the beginning of the 20th century. Only one of the southern windows of the chapel is original, moved from the upper floor of the late Gothic porch. Inside St. Woolos’ Church, the 15th-century piscina and the late medieval roof truss in the central nave and aisles are worthy of note. The 12th-century arcades between the nave and aisles have survived, along with the clerestory windows placed above them, now hidden under the roofs of the aisles. The greatest treasure of the church, however, is the 11th-century Romanesque portal, separating the nave from the chapel of St. Mary. It incorporates columns with elegant entasis, probably from nearby Roman Caerleon, although the most eye-catching are the bas-relief capitals and archivolts. Unfortunately, the tympanum of the portal has not survived, lost in the 19th century.

bibliography:

Caröe W.D., St Gwynllyw’s Church, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 88/1933.

Knight J.K., Wood R., St Gwynllyw’s Cathedral, Newport: the Romanesque archway, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 155/2006.

Morgan O., St Woolos Church, Newport, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, vol. 2, 8/1885.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.