History

The first castle in Montgomery was erected in the years 1071-1074 near the former Roman fort and controlled the same ferry across the Severn River, as its earlier Roman counterpart. It was built by Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, a native of St Germain de Montgommeri in Normandy, whose name passed later to the later Welsh town and castle. The stronghold which Roger built, became known as Hen Domen and was a motte and bailey wood-and-earth structure, located slightly more north than the later castle. After the death of Roger in 1094, Hen Domen passed into the hands of his descendants, and then it became a royal property and was given to Baldwin de Boulers, whose heirs kept it until the 13th century. In 1214, it was captured by Welsh forces led by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, and then burnt. However, the timber stronghold was rebuilt after 1223 and remained in use until about 1300, when it became useless as a result of Edward I’s campaigns, which led to the border being shifted far west and ultimately to the conquest of Wales.

The stone castle of Montgomery began to be built in 1223 on the initiative of the English king Henry III, after the surrounding land was recaptured from Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. The task of the new stronghold was to protect the strategically important Rhyd Chwima ferry and the Severn River Valley, a key road through the Welsh borderland to the Midlands. The builder of the new stronghold was also Hubert de Burgh, royal justiciar, later Earl of Kent, who also supervised the construction of the castles in Skenfrith, Grosmont and Whitecastle. Work on the upper castle advanced quickly, lasted until 1228, and was only briefly interrupted in that year by the unsuccessful attack of Prince Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. Over £ 3,600 was spent during this period to pay for workers, the garrison and the clearing of the surrounding forest to prevent a surprise attack. Probably at the same stage two outer wards were attached to the upper castle, which, however, were of wooden construction until the middle of the 13th century.

The stronghold was attacked again in 1231. It is true that the castle was probably defended, but the newly founded town was burned down. A year later Hubert de Burgh, deprived of royal favor, lost Montgomery, which became the property of the Crown. This became an opportunity to carry out repairs, roofing the gatehouse and renovating the well tower, which had to have structural problems due to the unusual structure. In the years 1251-1253, the castle constable on behalf of King, Guy de Rocheford made a thorough rebuilding of the still wooden middle ward into stone fortifications. A year later, Montgomery was handed over to Lord Edward, later King Edward I.

In the mid-thirteenth century there was a conflict between England and the Welsh led by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, grandson of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, Prince of Gwynedd. In 1257 he invaded the Severn River Valley, banished the local Powys ruler, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, and once again burned the town of Montgomery. Over the years, the Welsh prince grew into such strength that king Henry III met him at Montgomery Castle in 1267 and officially recognized him as the Prince of Wales. After Henry’s death, relations between Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and the new King of England, Edward I, deteriorated. The First War of Welsh Independence that broke out in 1276 ended in the defeat of Gruffudd and English control over all of East Wales. Montgomery then lost its status of a border fortress, although in the following years Edward I ordered the expansion of the castle, including the construction of a new great hall with auxiliary buildings (kitchen, bakery) and renovation of the castle walls. In addition, in the years 1279-1280 he ordered the rebuilding of the town walls into stone ones and strengthening them with towers. During the Second War of Welsh Independence in 1282, Montgomery played a key role as a meeting point for one of the three English armies. After 1295 and the final Welsh defeat, the castle lost its strategic importance and served more as a prison than fortresses.

In 1330 the castle was given to Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, but its fall in the same year brought the stronghold back to the Crown. Montgomery remained in royal hands for the next twenty-nine years, but because of the stable situation in Wales, it was increasingly neglected. It returned to the Mortimers in 1359, who, despite having many other castles (e.g. Wigmore, Dolforwyn) probably carried out the necessary renovation works and raised the level of housing conditions. The castle was yet strong enough to resist the attack of the Welsh insurgents of Owain Glyndŵr in 1402. Unlike the castle, the town was captured and plundered. Montgomery was in Mortimer’s hands until 1425, when it returned to the king again and was then handed over to Richard, Duke of York.

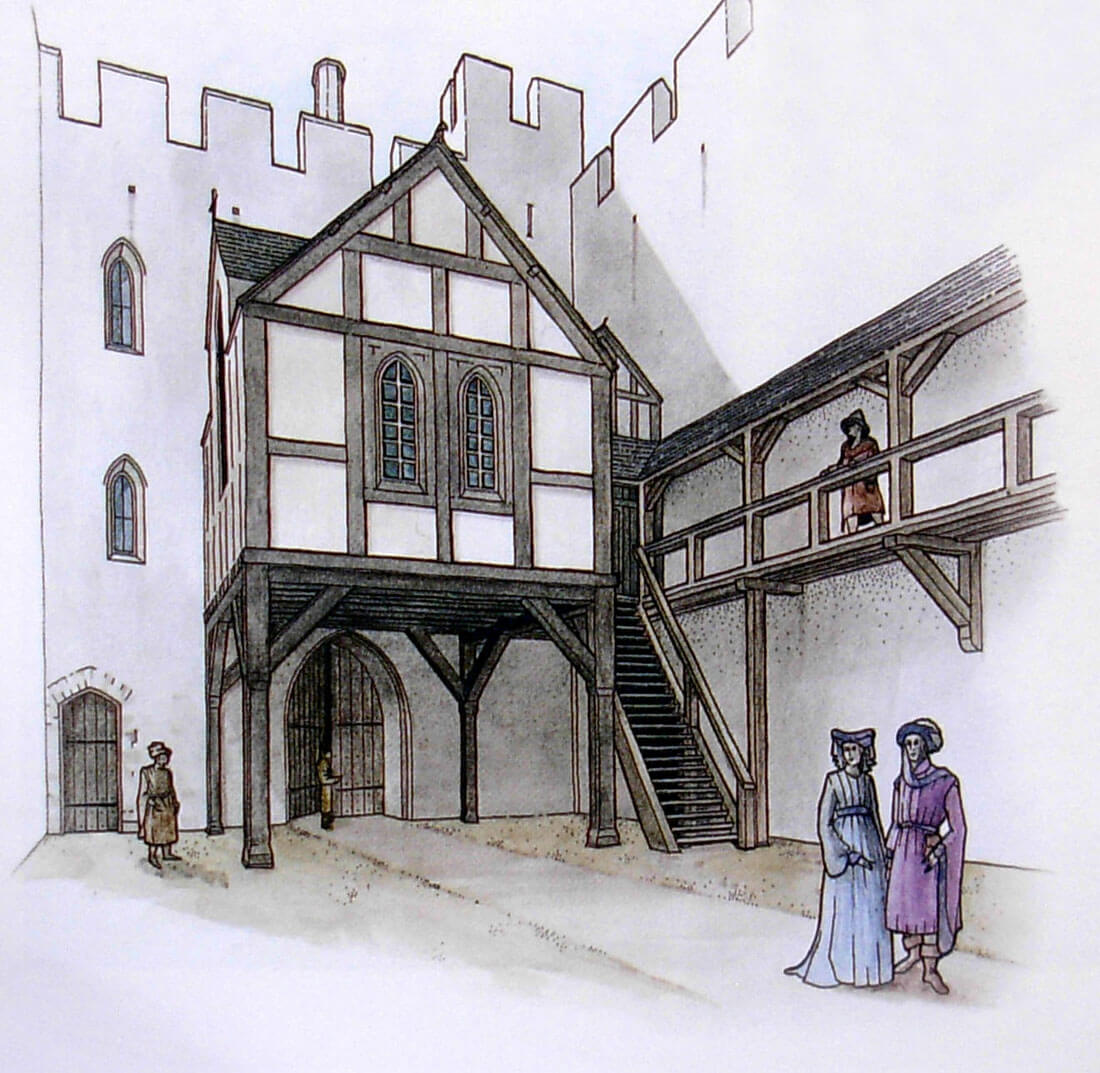

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Montgomery Castle was in bad condition, but in 1534 Rowland Lee, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, made it one of the key administrative centers and began modernizing internal buildings, and in the early seventeenth century, Sir Edward Herbert began building a timber manor in the area of outer ward. The location of the castle on the sidelines of the English Civil War, meant that it did not take part in the fighting during the first few years of the war. However, after the critical defeat of the royalists at the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644, parliamentary forces began their offensive at the Welsh border. The then owner, Lord Herbert, surrendered the castle to the news of the approach of the opponents. The loss of Montgomery limited the royalist movements in Central Wales, so their large army was gathered to take back the stronghold and the town. Likewise, Parliament did not want to lose an important point, and two armies met in the Battle of Montgomery on September 18, 1644. As a result, the royal forces were defeated. Sir Edward Herbert died in 1648, and as his heir was an active royalist, the castle was demolished by order of Parliament to prevent its future military use.

Architecture

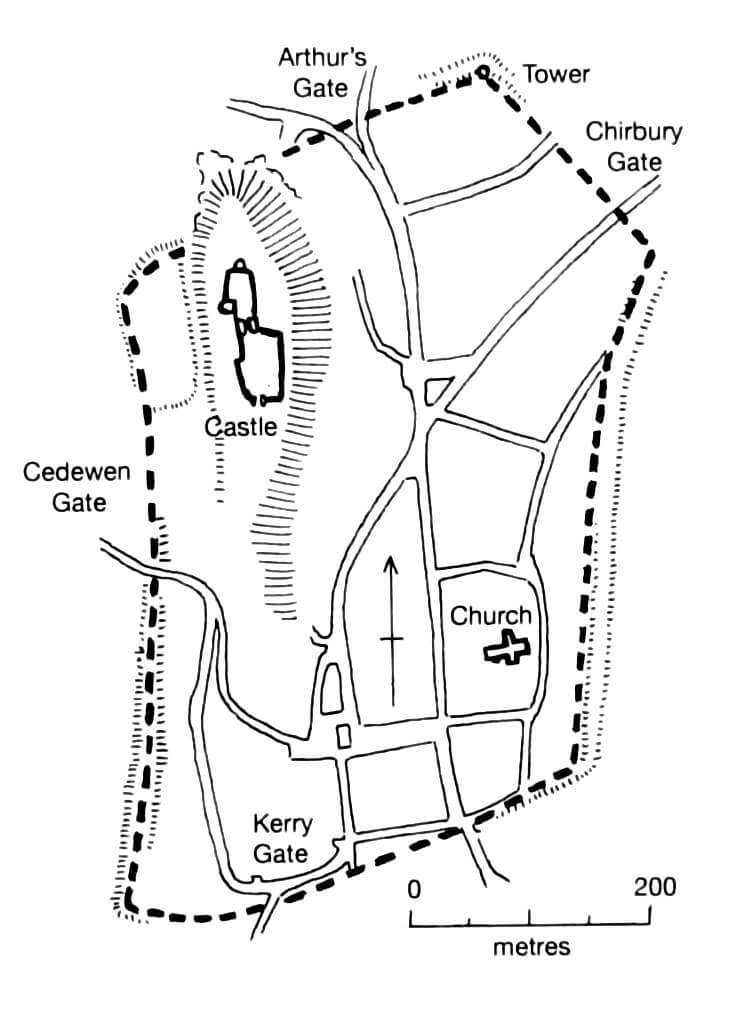

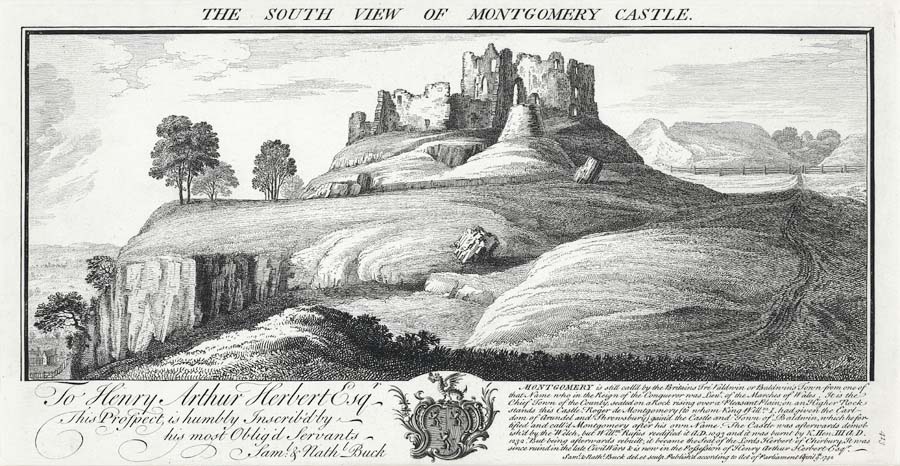

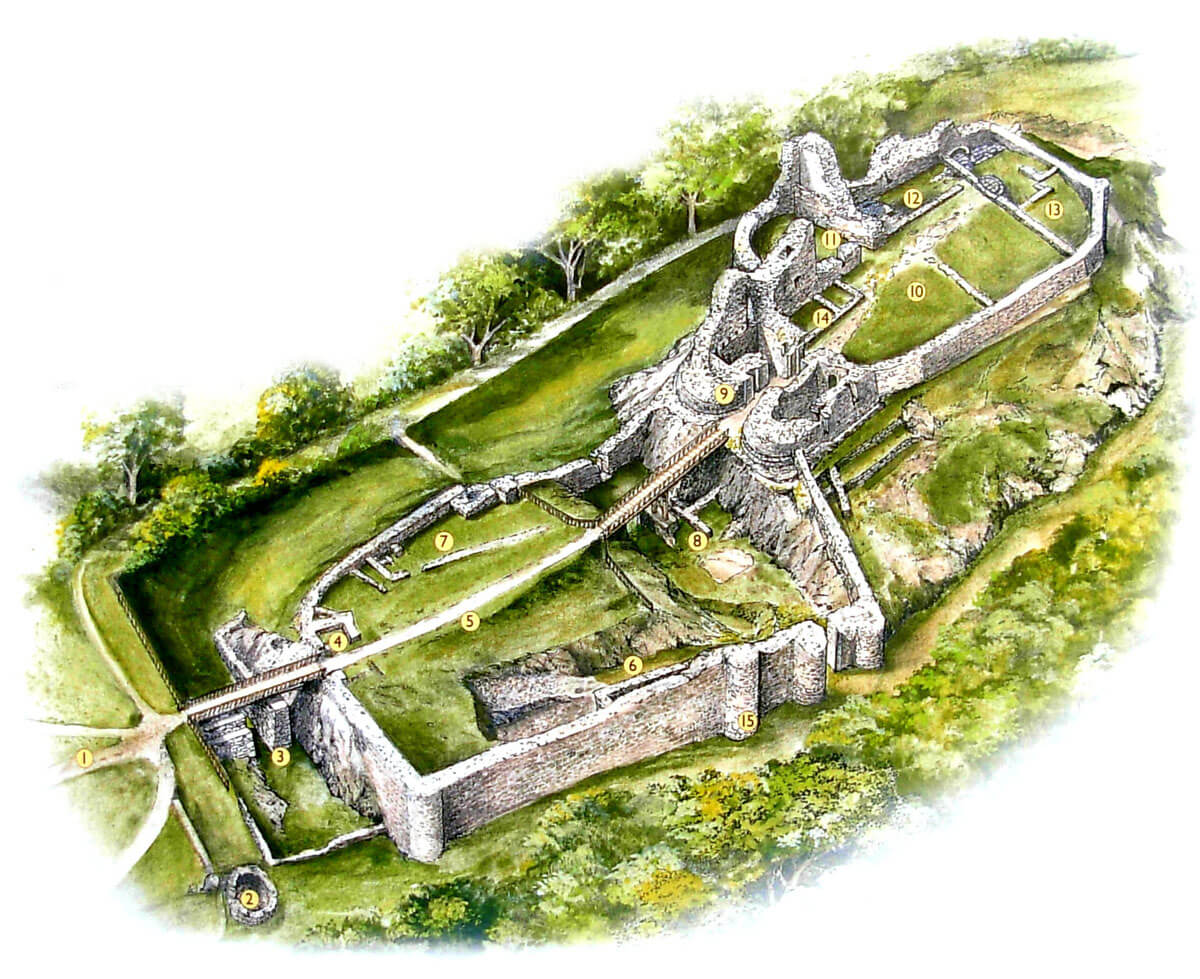

A limestone ridge was chosen for the construction of the castle, towering over the surrounding plains. Its slopes were the most inaccessible from the east and north where the ground was formed by rock formations, but also from the west, the approach could cause problems. Montgomery consisted of the upper ward and two outer wards (middle and lower ward) located south of it, which due to the form of terrain received a very elongated shape. To the south-east of the castle, a settlement developed over time, then expanded into the fortified town of Montgomery, whose defensive walls in an area of about 600 x 400 meters almost completely surrounded the castle hill and town buildings, reaching the rocks in the northern part of the castle ridge. They were reinforced with quite rarely spaced towers (probably located mainly in the corners) and four gatehouses.

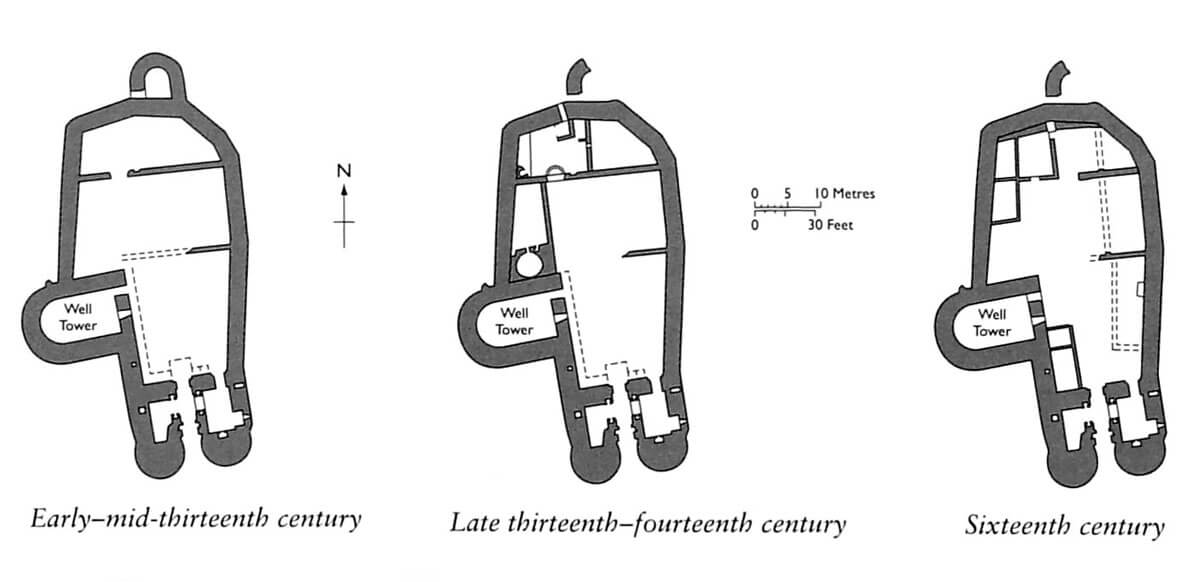

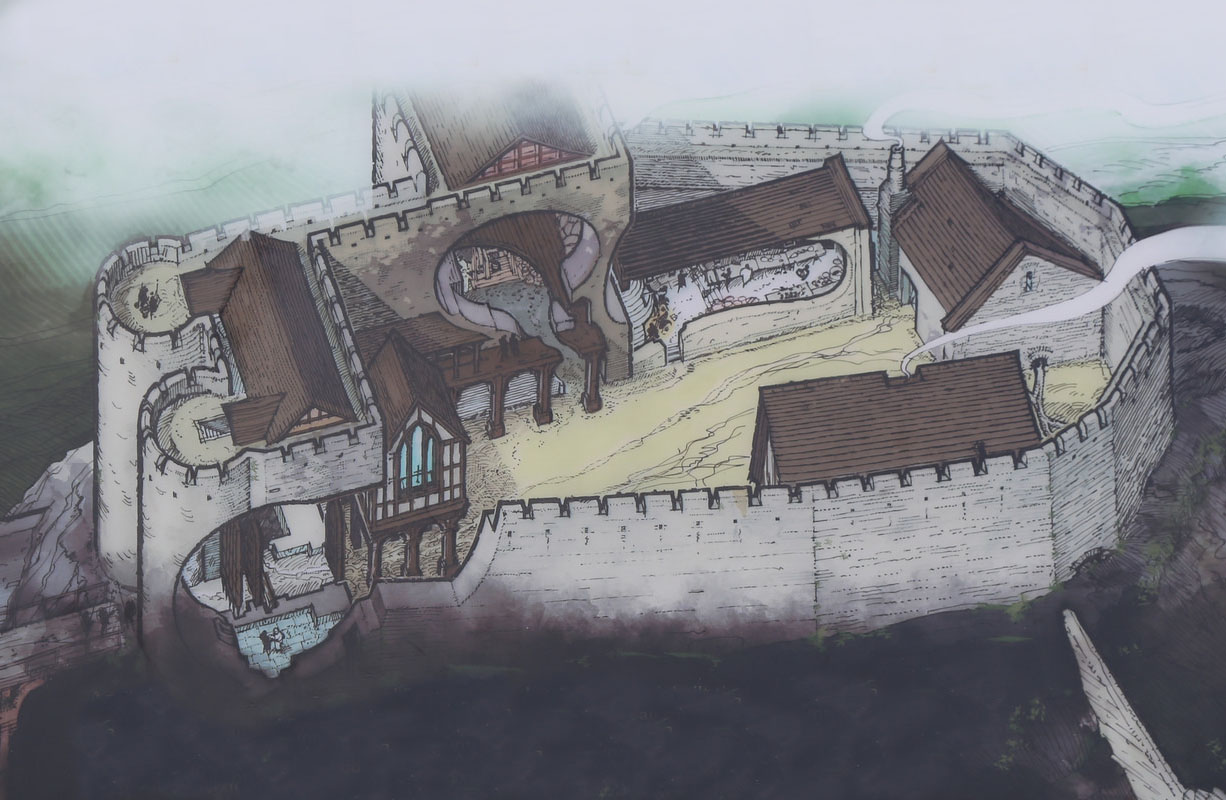

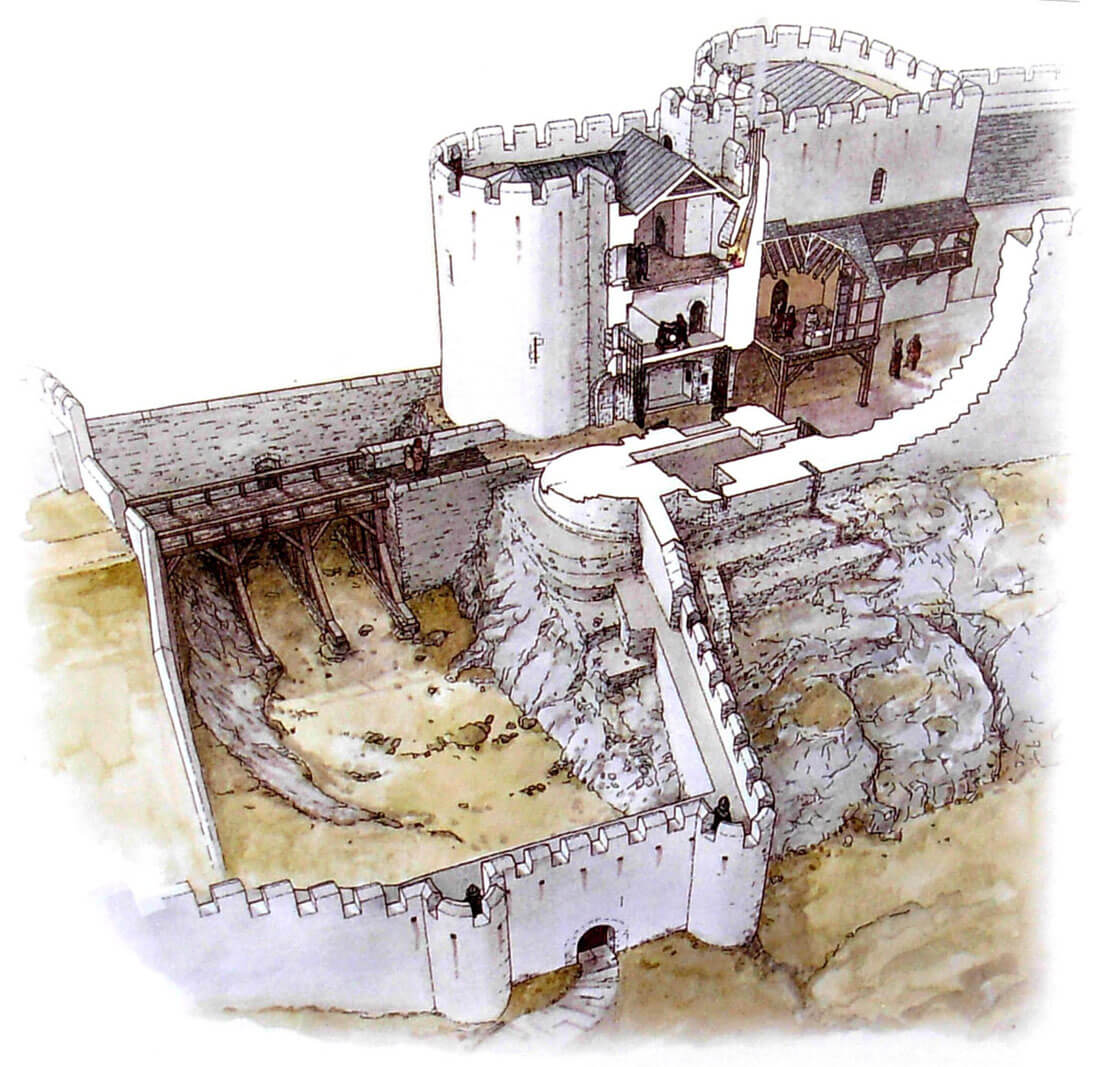

The upper ward measuring 39 x 22.5 meters was built on a rocky promontory, protected from the north, east and west by the escarpments, especially steep and high from the east. The inner courtyard was surrounded by a defensive wall with an entry gate on the south side. It consisted of two massive horseshoe-shaped towers flanking the passage between them. In front of the gate there was a drawbridge above the rock cut ditch, 13.7 meters wide and 6.1 meters deep, with almost vertical slopes. The bridge was a three-span, wooden structure, passing closer to the gate into the stone part. The passage itself, 2 meters wide, was defended by a portcullis embedded in the grooves and two doors – one at the beginning and one at the end of the passage. Probably also a shooting hole in the ceiling was pierced, that is a murderhole that allowed fire from above (this is indicated by the accidental death of a certain Maud Vras in 1288, killed by a carelessly dropped stone from the upper room). The side walls of the passage have been formed into niches with benches at the bottom and smaller recesses on the sides resembling cupboards. Originally, they were equipped with grilles or wooden doors and could be used to place oil lamps illuminating the dark gate passage. Each of the gate towers had a four-sided room at the ground floor, which was originally not accessible from the passage. It wasn’t until later period that the door to the western room, which perhaps served as a prison or warehouse was pierced (it was previously accessible only by means of a ladder from the upper room). The eastern room intended for the castle guards had an entrance portal from the side of the courtyard, closed with a door and a drawbar placed in the thickness of the wall. Its only lighting was a slotted opening from the east, and on the opposite side the guard could operate the drawbar of the main gate. The front, rounded parts of the towers were full, constituting a massive barrier resistant to possible fire, while on the upper floors of the gatehouse, in addition to portcullis mechanism, there were living quarters with, inter alia, a latrine (its drainage channels were directed towards the ditch). This was described in 1250 so-called a knight’s chamber on the first floor, used for the everyday life of the household and the private chamber of the castle lord on the top floor. From the side of the courtyard, the gatehouse had timber stairs leading to the upper floors and an protruding wooden or half-timber chapel. The stairs also connected to the wooden porch at the tower with the well.

The next element of the upper ward was a tower on the west side, built on the plan of an elongated horseshoe measuring approximately 12 x 15 meters. It was extended beyond the defensive perimeter and beyond the rock platform on which the castle was erected, in order to be able to put a well in it. Due to construction faults (foundations too weak), it was completely rebuilt in the 14th century. A 64-meter long shaft drilled in by miners in rock led to the well. This hard work was probably due to the fall of the nearby Dolforwyn Castle, precisely because of the lack of water supply. In addition, at the upper ward courtyard, additional buildings were attached to the western, northern and eastern curtain of walls, some or all of which could have been wooden or half-timbered. Among them was the “old hall”, mentioned in the middle of the 13th century. After 1280, an L-shaped range was erected in its place to house the kitchen and the brewhouse. The kitchen, located right next to the tower with a well, housed a massive round oven formed of thin stone plates at the edges and covered with a layer of brick-clay cover. Above it originally could have been a brick dome and chimney, and food was prepared on an oblong wooden table running along the entire length of the kitchen. Three shallow stairs led down to the brewery, while inside barley was soaked in square tanks by the north wall. Then it germinated on the paved floor on the west side, it was boiled in a small oven and ground in a handmill. The remaining fermentation and brewing process was carried out on the upper floor, from where the liquid could flow down by means of gravity into the bottom tank. To the east of the brewhouse there was a series of chutes to drain waste and debris outside the castle. It is worth mentioning that in the northern corner of the courtyard there was originally a postern gate, blocked only with the construction of the brewery. It was defended by a horseshoe northern tower, which probably was destroyed or dismantled yet in the Middle Ages. In the last phase in the 16th century, the courtyard of the upper castle was surrounded by half-timbered, storeyed residential buildings.

The middle ward with dimensions in the plan 60 x 37 meters, originally defended by a wooden palisade, received stone fortifications slightly later than the upper ward, in the years 1251-1253. This wall was about 2 meters thick at the base. The entrance to its courtyard was on the south side and was preceded by a 13.7 meter wide and 6.7 meter deep ditch. Due to the large width of the ditch, the bridge was mounted on a stone platform, behind which there was a raised part of the bridge. The main defensive role was played by a two-tower gatehouse (each tower was about 7 meters in diameter) with a centrally located passage, similar to the one from the upper castle, but slightly smaller. The middle ward from the east was defended by a wall equipped with small semi-circular turrets protruding in front of its face with finials in the form of wooden platforms. Two towers were built in the mid-thirteenth century, the third one on the south, not bonded to the wall, was added in the fourteenth century. Older towers protected the postern gate, pierced in the wall protecting access to the ditch separating the middle ward from the upper ward, and an additional fourth turret in the south-east corner flanked the entrance gate. From the south and west, the defense of the middle ward was provided by a simple defensive wall, probably topped with battlement and wall-walk for defenders. The internal buildings were probably attached to the perimeter walls and consisted of economic and auxiliary houses for servants and the garrison. In the Middle Ages it probably had a wooden or half-timbered structure on a stone foundation. In the 16th century they were replaced by new quarters with a latrine on the north-west side. Near the eastern curtain was a 14th-century building intended for drying grain after harvest. The fire was kindled at the base of its chimney, and the warmth heated the grain on the upper platform.

The outer ward was located the lowest of the three parts of the stronghold, on the southern part of the ridge. Its fortifications were mostly of wood and earth, with the extreme southern end taking the form similar to a horseshoe redoubt, and in the middle of a spacious courtyard, on a slight elevation of the land, an independent, closed defensive work was probably built. The eastern part of the fortifications, probably transformed into a stone wall over time, was connected with the south-eastern part of the middle ward, while the western part ran to the north, covering both the middle and upper ward.

Current state

The castle has survived in the form of a poorly preserved ruin. There are mainly visible low fragments of the walls of the middle and upper ward, one of the walls of the gatehouse and fragments of the horseshoe tower of the upper ward. The monument is open to visitors for free, from April 1 to June 30, every day from 10:00 to 18:00 and from July 1 to September 15, every day from 10:00 to 21:00.

bibliography:

Butler L., Knight J., Dolforwyn Castle, Montgomery Castle, Cardiff 2004.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., Medieval walled towns, Malvern 2013.

Salter M., The castles of Mid Wales, Malvern 2001.