History

The Cistercian Abbey of Margam was founded in 1147 by Robert, Earl of Gloucester, who short before his death donated lands between the rivers Afan and Kenfig, near the old Roman road that run towards West Wales, to the Clairvaux monastery in France. The first abbot was William of Clairvaux and Robert’s son and heir, William of Gloucester, confirmed and even extended the grants given to the abbey. For about forty years since foundation a Romanesque church and monastic buildings were built, but shortly after their completion, in the second quarter of the 13th century, wanting to be up to date with contemporary architectural trends, the entire eastern end of the abbey church was rebuilt in the style of early English Gothic.

The abbey at Margam quickly gained importance in the social, cultural and religious life of South Wales. In the second half of the 12th century, the Welsh chronicler, linguist and writer Gerald (Giraldus Cambrensis) celebrated the abbey for his alms and charity, although he also mentioned the incident of 1180, when a young man attacked and beat someone in the guest’s refectory, and the next day he was found dead. At the end of the 12th century, problems with the Cistercian lay brothers intensified, for which the abbot Conan (Cynan), who allegedly had unsuccessfully forbidden to drink beer, was condemned by the general chapter. In 1206, the lay brothers rebelled again, attacking Abbot Gilbert and the monk managing the monastery cellar. They were supposed to throw them off the horse and then chase them to the dormitory, where they both barricaded. According to Gerald, it was a reaction for mistreatment of lay brothers and further bans on drinking beer in the granges subordinate to the abbey.

In 1203, the Margam Abbey received papal confirmation of its goods and privileges, and two years later the royal one, issued by king John. With this ruler, the Cistercians from Margam maintained exceptionally good relations, unlike the Cistercian monks from Strata Florida. John stayed twice on the abbey on his way to Ireland, and perhaps in exchange for this hospitality, he exempted Margam from taxes imposed on other abbeys. A good period for the monastery was also the time when abbots John of Goldcliff (1213–1237) and John de la Warre (1237–1250) held office, when, among other things, another royal confirmation of privileges was received, this time issued by Henry III. Serious losses were not recorded until 1247, when due to the assault on the abbey’s property by Morgan ab Owain, although monks were later able to obtain compensation. Shortly afterwards, in 1268, several granges and arable lands were seized by Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, which was still complained to King Edward by the general chapter of the Order in 1291.

At the end of the 13th century Margam was one of the richest abbeys in Wales with an annual income of £ 256, 2,600 hectares of arable land and 2,000 sheep. The Cistercians, as many as 38 monks and 40 lay brothers in 1336, were also involved in profitable mining of iron, lead and coal, as well as in horse breeding. It was not until the mid-14th and 15th centuries that the community suffered from floods, animal diseases, increased taxation, plague and Welsh rebellions. Major damages were recorded especially in 1412 during the Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr. They were inflicted by insurgents because of the favorable attitude of the monks towards the English, though paradoxically, Margam Abbey at the end of the Middle Ages played an important role in the development of Welsh culture. Among others, Latin Annales de Margan was created here, a key source for the history of Glamorgan, as well as Book of Taliesin, one of the most famous Welsh manuscripts, containing a collection of the oldest Celtic poems.

The abbey was dissolved by the king of England Henry VIII in 1536 and sold to Sir Rice Mansel. At that time, only 12 monks lived in the monastery (compared to 38 monks and 40 lay brothers in the fourteenth century). After the Mansel family, the abbey went over to the descendants of the feminine line, the Talbot family. In the nineteenth century, one of its members built a residence near the abbey, but the nave of the monastery church was still used as a parish church.

Architecture

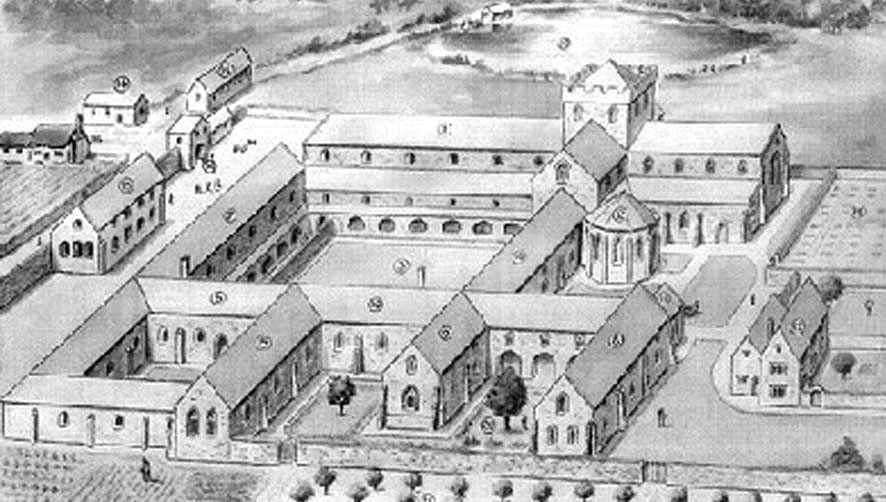

The abbey was founded at the southern base of a forested massif of hills, from which numerous streams flowed towards the Bristol Channel, providing water necessary for everyday functioning. At least one of the streams was regulated by the monks and led to economic buildings and latrines in the form of a canal. Others were also used to create fish ponds. The monastery consisted of a church and the claustrum buildings adjacent to it from the south, traditionally surrounding the garth with cloisters. On the western side, there were more loosely scattered economic and auxiliary buildings, along with the main entrance gate to the abbey. The whole area was probably fenced already in the Middle Ages.

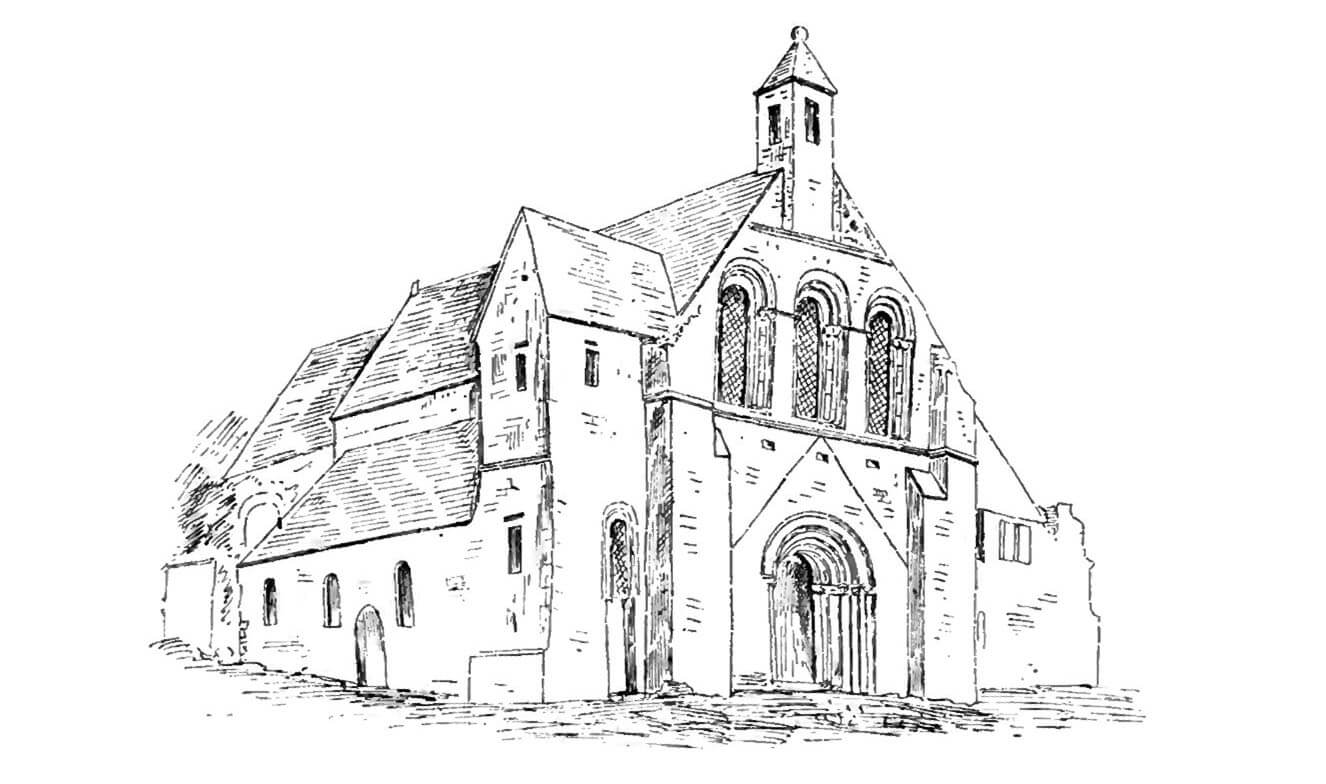

The monastery church was eight-bay basilica with central nave and two aisles, approximately 80 meters long, built on a Latin cross plan, with a central four-sided tower at the crossing, two arms of the transept and a spacious five-bay chancel with two aisles, ended with a straight wall on the eastern side. According to the traditional arrangement of Cistercian churches, two chapels were adjacent to both arms of the transept on the eastern side. All of them, like the chancel, ended with straight walls from the east. The western part of the church was built in the Romanesque style, while the eastern part was the result of an early Gothic reconstruction, although the whole probably created a fairly homogeneous shape, typical of Cistercian churches. The building was distinguished by relatively thick walls, approximately 1.5 meters wide in the nave.

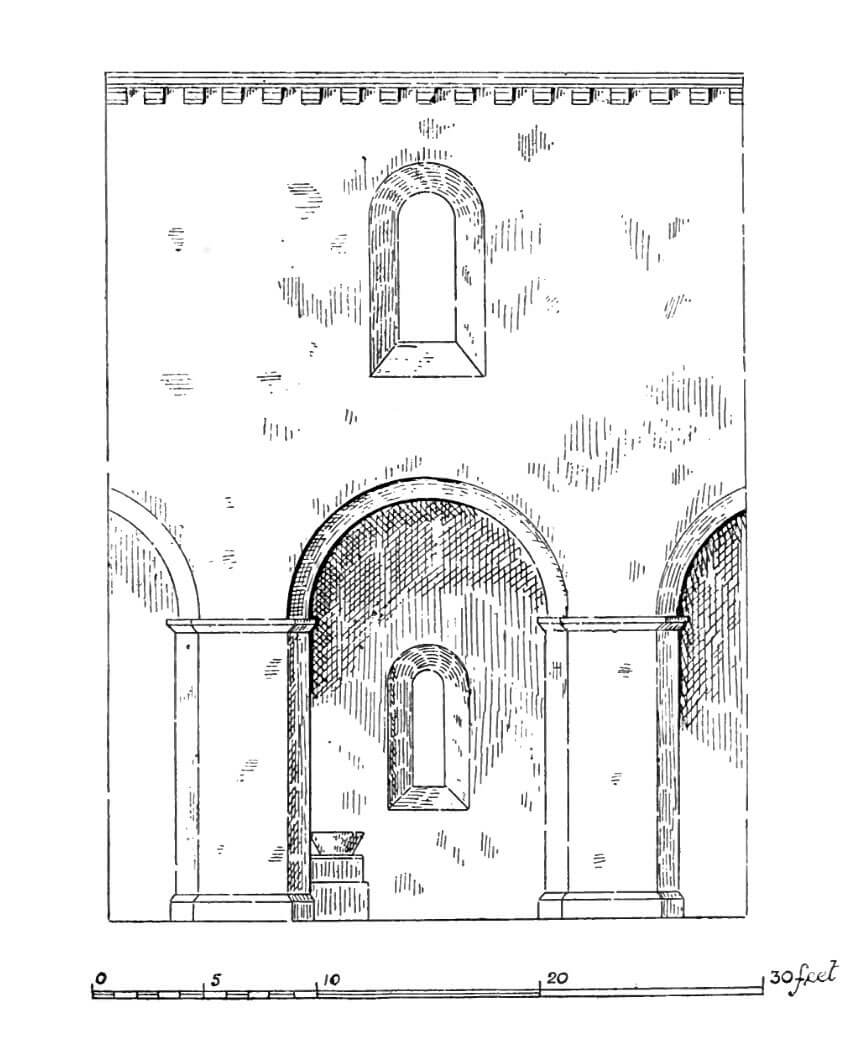

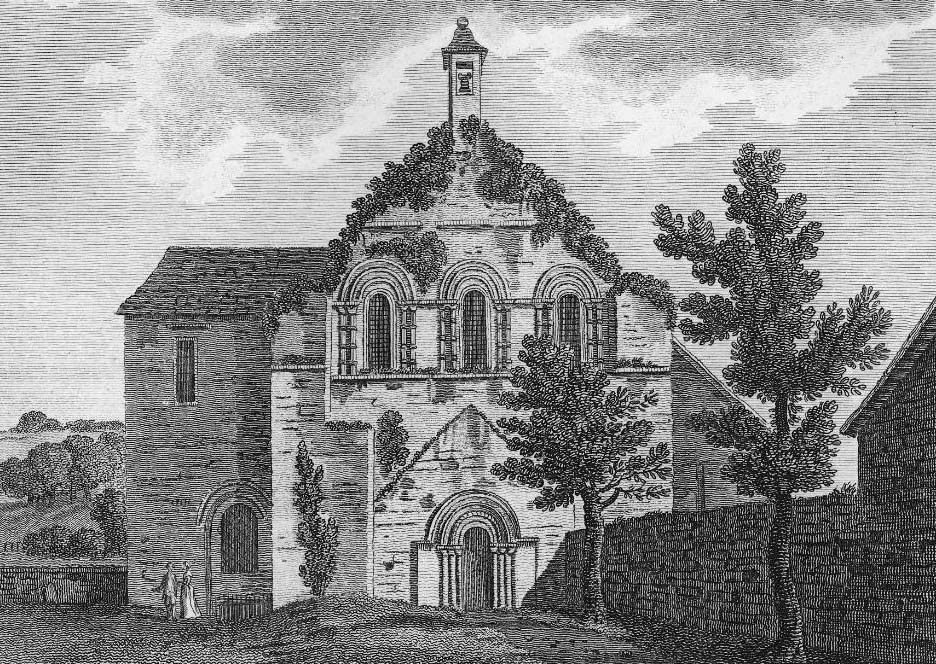

The main entrance to the church was located in the western façade, on the axis of the central nave, perhaps preceded by a porch with a gable roof. It led through a stepped portal with a semicircular archivolt, in which three columns with capitals on each side were inserted. Above there were three windows with a similar moulding, all semicircular, with archivolts supported by two columns on each side. The central nave from the side aisles, each with a single western window, were separated on the façade by massive buttresses – lesenes. The side chapels and the chancel, which probably already had lancet windows, were surrounded by slimmer and more closely spaced buttresses. Inside the nave, the semicircular arcades between the aisles were based on massive, four-sided pillars with vertical offsets in the corners, straight plinths and narrow cornices in the capital zones. The four pillars at the crossing, supporting the four-sided tower, must have been more massive and impressively moulded.

From the south, the nave of the church adjoined a vast garth surrounded by cloisters, with significant dimensions of 40 x 40 meters. The cloisters provided access to each wing of the claustrum, which adjoined the garth from the west, south and east. According to Cistercian practice, the eastern wing had to house the most important rooms related to the functioning of the monastery, such as the chapter hall, the sacristy and library adjacent to the church, monks day room and the dormitory, most often located on the first floor. For practical reasons the dormitories were combined with latrines on one side and with the church transept on the other, to facilitate the transition to night prayers. In Margam, latrines could be accessed via a three-bay porch set on pointed arcades, extending from the south-east corner of the claustrum. The southern wings of Cistercian abbeys customarily housed kitchens and warm rooms, adjacent to impressive refectory halls, very often located along the long axis across the building. The western wings were intended for pantries and storerooms (cellarium), as well as rooms for lay brothers, who performed physical work in the monastery.

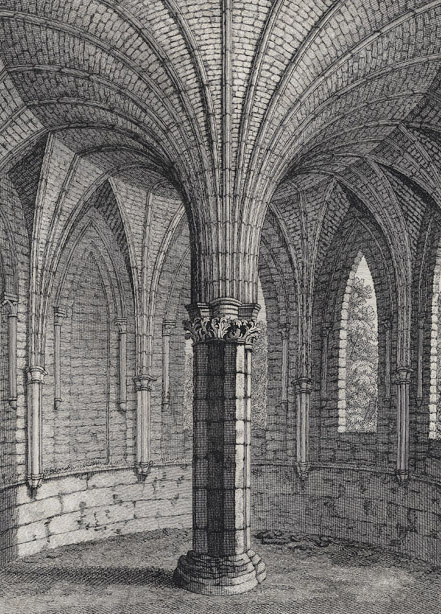

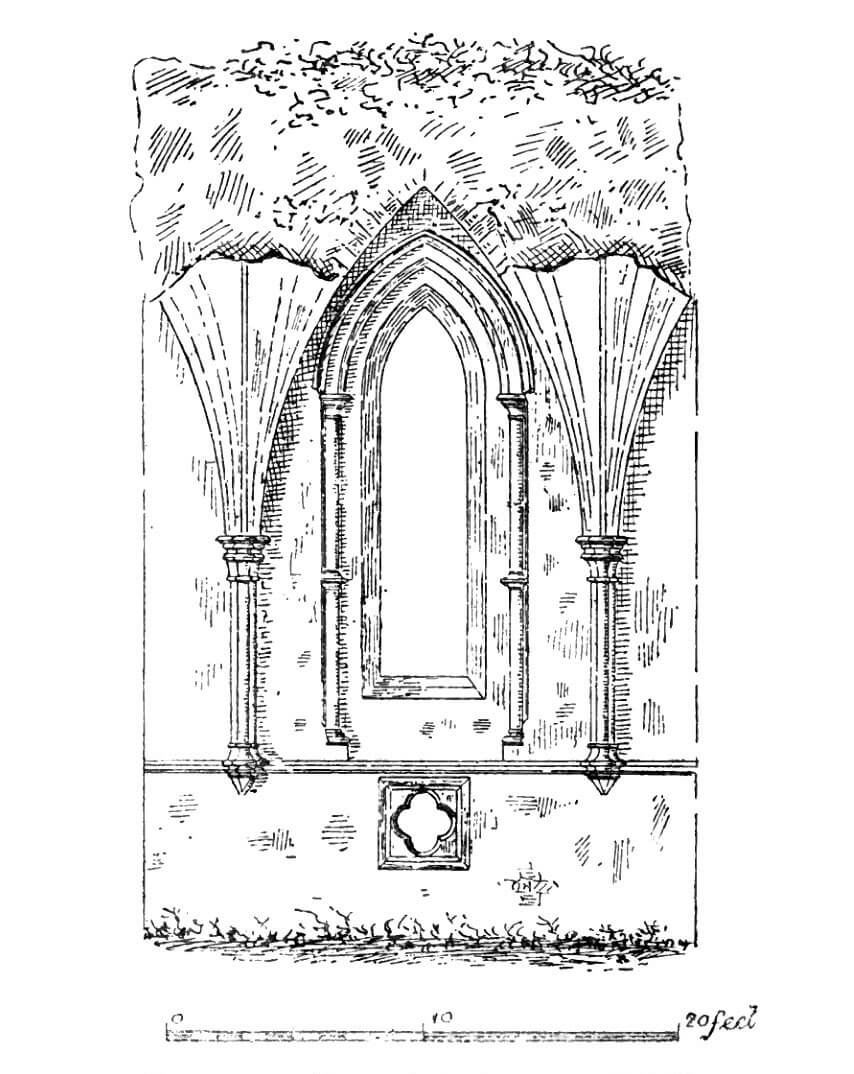

To the south of the chancel, a magnificent Gothic chapter house was built at the beginning of the 14th century, of a twelve-sided plan but circular inside, surrounded by shallow buttresses from the outside. Its interior was covered with a vault supported by a single pillar with a cross-section, enclosed by cylindrical shafts with capitals decorated with plant motifs. The entire structure was based on an octagonal, richly moulded plinth with bases. Thirty-six non-intersecting ribs without bosses were lowered onto twelve wall shafts, suspended on consoles above the floor, at the height of the cornice running under the window sills. The chapter house was connected by an ogival portal to the vestibule in the eastern wing of the claustrum, and this was connected to the cloister by means of an impressive ogival portal flanked by slightly lower side passages. The chapter house’s lighting was provided by nine large, ogival windows, placed in niches flanked by two shafts supporting archivolts. Additionally, in the eastern wall, just above the plinth, a moulded oculus was pierced, placed from the inside in a recess surrounded by a four-sided frame.

Current state

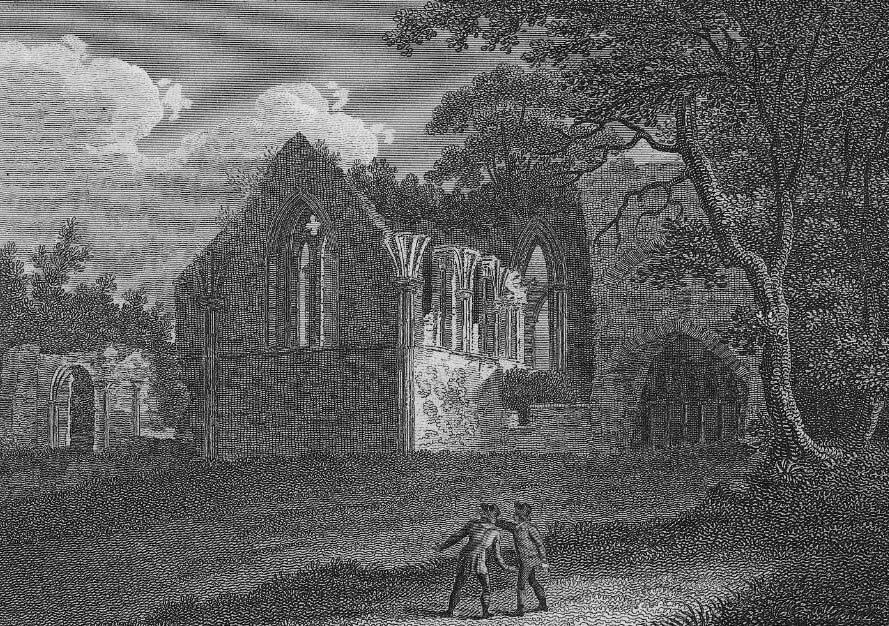

To this day has survived the twelfth century central nave of the abbey’s church, however shorter than the original one by two bays from the east. Unfortunately, the side aisles have been rebuilt, and the chancel, transept and the central tower have not preserved. In the form of a ruin there is the chapter house, now without the vault that collapsed due to neglect at the end of the 18th century, but with a preserved central pillar. There are also visible relics of the eastern wing of the claustrum, adjacent to the chapter house, and annex in the south-east.

Among the architectural details that have survived in the monastery, there are the southern portal of the chancel, the windows of the chapter house including the eastern oculus, the impressive entrance to the vestibule in front of the chapter house, the Romanesque portal and the windows of the central nave in the western façade of the church. The vault of the vestibule and the vault of the southern arcades have survived. Inside the church, the late Romanesque pillars between the aisles are original.

Today, the abbey area is owned by the County Council. It is open to visitors, including the lapidary museum (Margam Stones Museum), which houses, among others, a rich collection of Roman milestones and medieval grave crosses from the 9th-12th centuries. Among the latter stand out the monumental, richly decorated Cross of Conbelin from the beginning of the 10th century and the oldest in the collection, unfortunately damaged Cross of Einion from the 9th century.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Gray Birch W., A History of Margam Abbey, London 1898.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.