History

The Cistercian abbey of Valle Crucis was founded in 1201 by the ruler of northern Powys, Madog ap Gruffydd Maelor, the prince of northern Powys (Powys Fadog). The name of the abbey meant Valley of the Cross and referred to nearby Eliseg’s Pillar, a stone cross from the ninth century, set by Concenn of Powys to honor ancestors. As the Cistercian rule required the construction of the monastery in secluded places, the entire population of the village of Llanegwestl was forcibly transferred to Stantsy, near Wrexham, and only some received compensation for the loss of homes. In their place came thirteen monks from the Strata Marcella monastery, another Cistercian foundation supported by the princes of Powys.

Despite the convenient location, the first years of the abbey’s functioning were not without problems. After a year or two, the general chapter of the order received complaints about the abbot, who was to celebrate masses too seldom, and in 1234 he had problems due to the admission of a woman to the cloisters. Ultimately, however, his explanations had to be convincing, because the chapter considered this only as a light fault.

In 1236, the founder, Madog ap Gruffydd Maelor, was buried in the abbey. It is believed that the monastery church was already partly completed then (chancel), but in the same year a great fire destroyed the abbey buildings, forcing further construction works. The church was probably rebuilt until 1269, because Gruffudd Maelor, son of the abbey founder, was buried there, and in 1306 his great-grandson, Madog ap Gruffudd. This indicates a strong connection between Valle Crucis and the North Welsh native rulers, whom the brothers supported during the struggle with the English Crown. For example, in 1274, abbot of Valle Crucis named Madog wrote to the Pope in defense of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the last independent prince of Wales. In thanks, Llywelyn granted the abbey a loan of £ 40 in the following years. Unfortunately, the fact that all the monks were native Welsh and the political connotation of the abbey caused damages during the Anglo-Welsh wars during King Edward I reign in 1276-1277 and 1282-1283, becoming the target of English troops. It is known that the king after the victorious end of wars offered monks twice compensation for damages caused by his men. Quite quickly, relations between Edward and the abbey were normalized, because in 1294 he appointed abbot of Valle Crucis to manage the estate of Roger of Mold, who was then in Gascony, and a year later the king personally visited the monastery making a n oblation at the main altar.

About 20 monks and 40 lay brothers of the order lived in the completed abbey, who performed their daily duties, including farm work. The main source of income, however, was the income from the seven subordinate parish churches, making Valle Crucis one of the four richest Cistercian convents in Wales. In the second half of the fourteenth century, the number of monks fell, probably due to the devastating effects of the plague, although despite this, ambitious construction works were carried out, especially in the east wing and chapter house. At the beginning of the 15th century, Valle Crucis suffered damages during the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr, repaired after 1419 during the abbot Robert Lancaster’s office. The prosperity of the abbey increased at the end of the 15th century for three successive abbots: Siôn ap Rhisiart, Dafydd and Siôn Llwyd, who gained the considerable reputation of scholars and patrons. The monastery then became known for its hospitality, where several well-known Welsh poets and bards, such as Gutun Owain or Tudur Aled, spent their time here, and one of them, Guto’r Glyn, spent the last years and was buried here in 1493.

The end of splendor was brought by the reformation and dissolution of the convent by Henry VIII in 1537, preceded by the election of abbot of the wrong candidate in the person of Robert Salusbury. Already before the election, he was involved in several extortion, assaults and thefts, and the choice itself aroused such controversy that five out of the last seven monks then went to other monasteries. Robert was eventually removed, and a few years later he was imprisoned in the Tower of London, but the finances of Valle Crucis were in such a pitiful state that the last abbot John Durham was unable to save it from cassation (according to Henry VIII’s decree all monasteries were dissolved with an annual income below £ 200, Valle Crucis had a income of £ 188 but was neglected and ruined.) In 1537, the monastery buildings were rented to Sir William Puckering and his descendants. At the end of the 16th century, the east wing of Valle Crucis was transformed into a manor, and at the end of the 18th century the building, which has not yet turned into ruin, was roofed again and began to be used as a farm. The first security and excavation works were undertaken in the 19th century.

Architecture

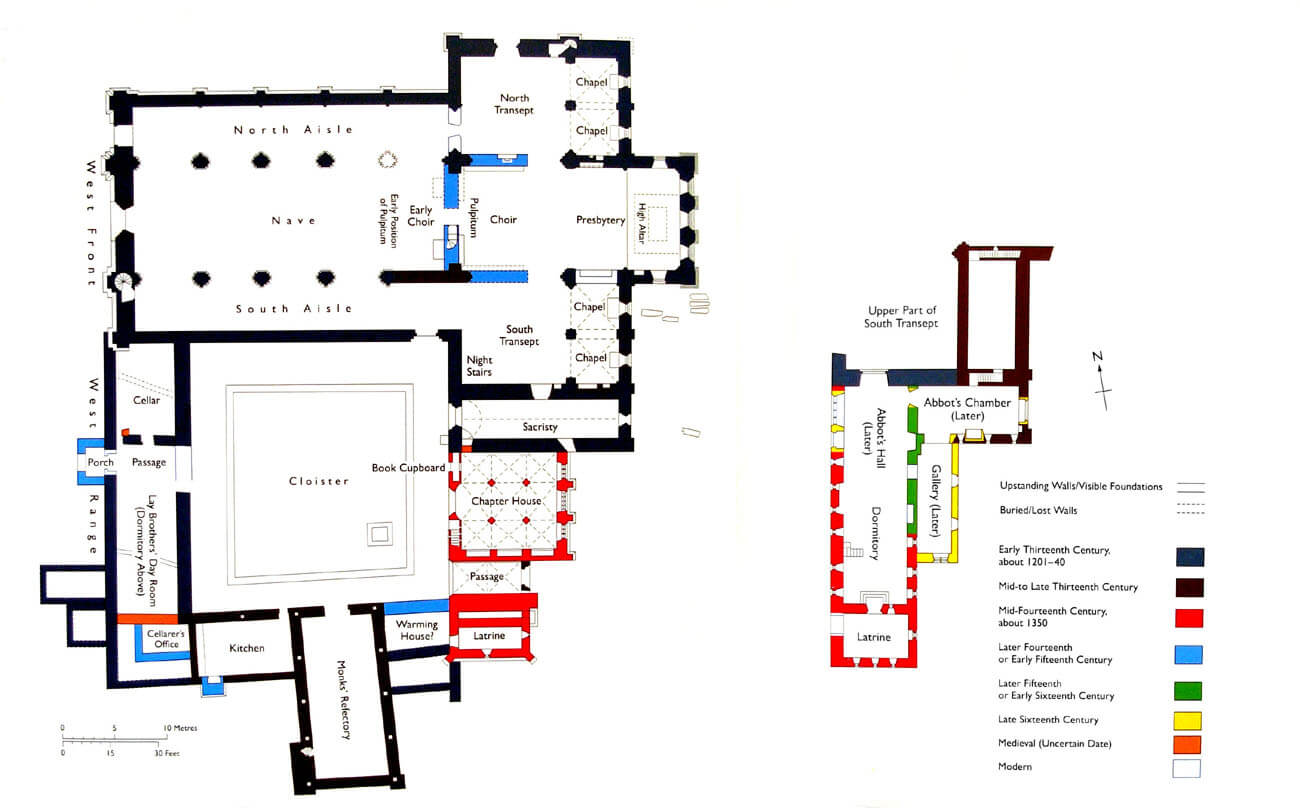

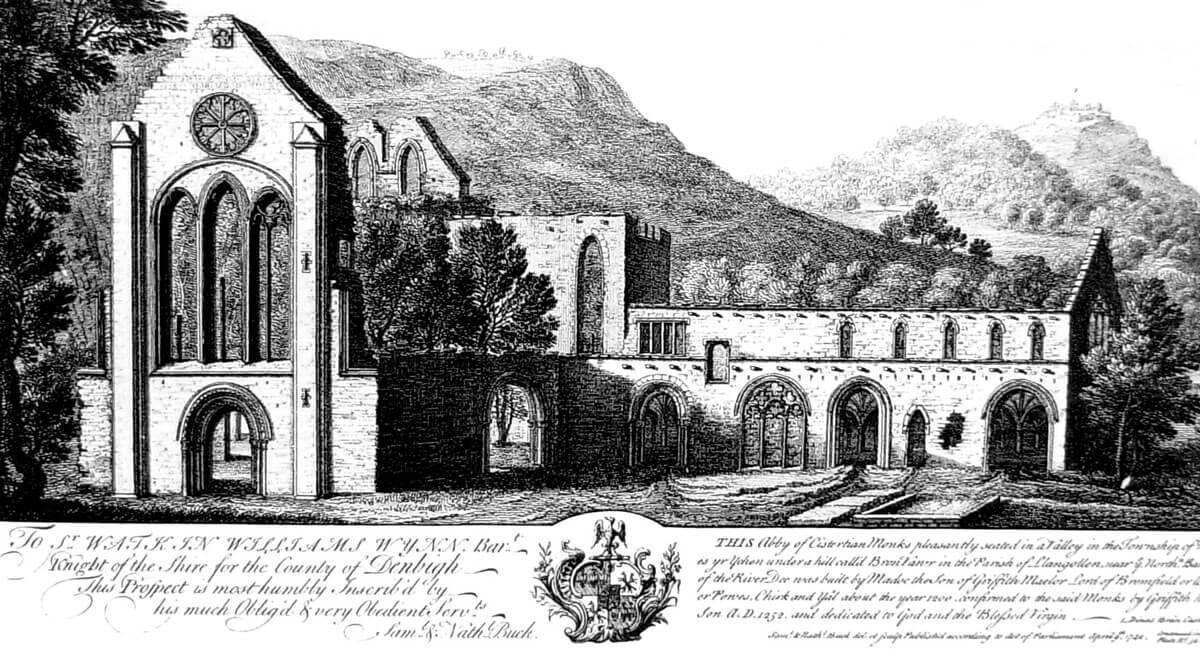

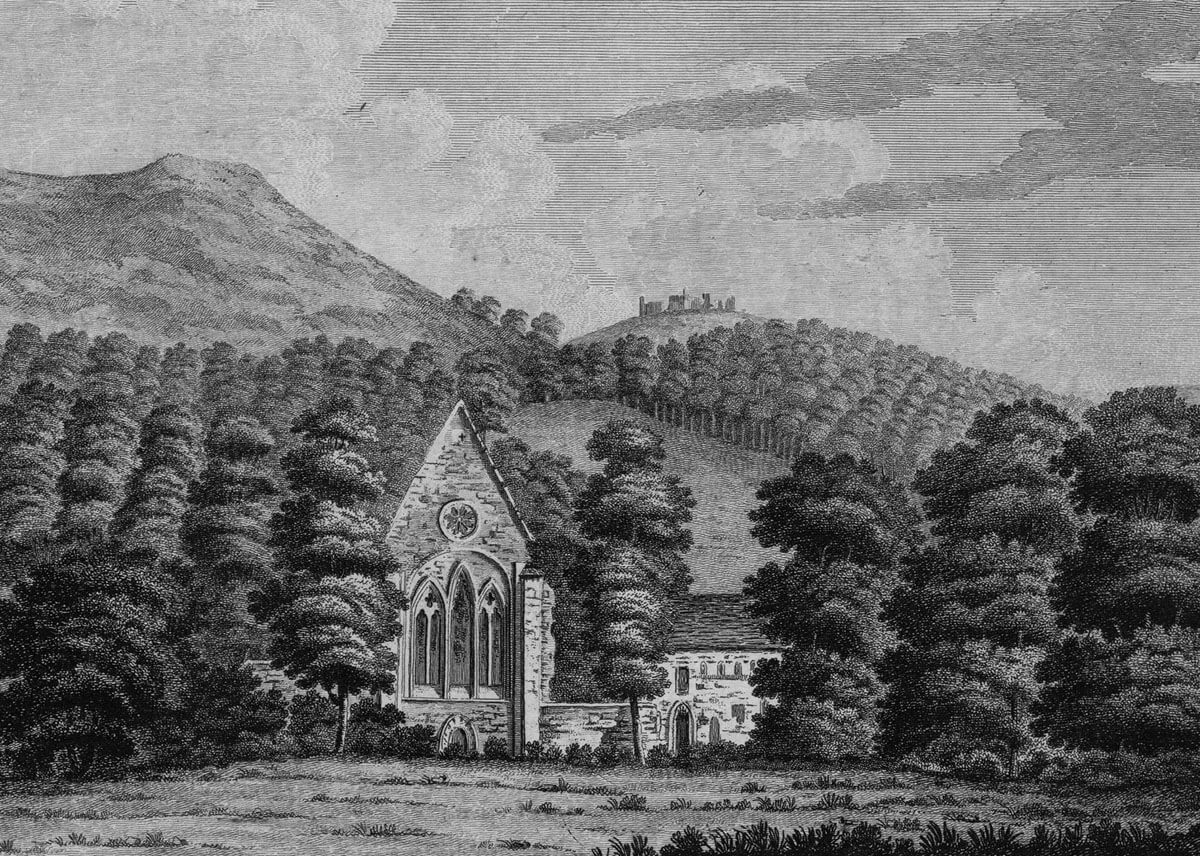

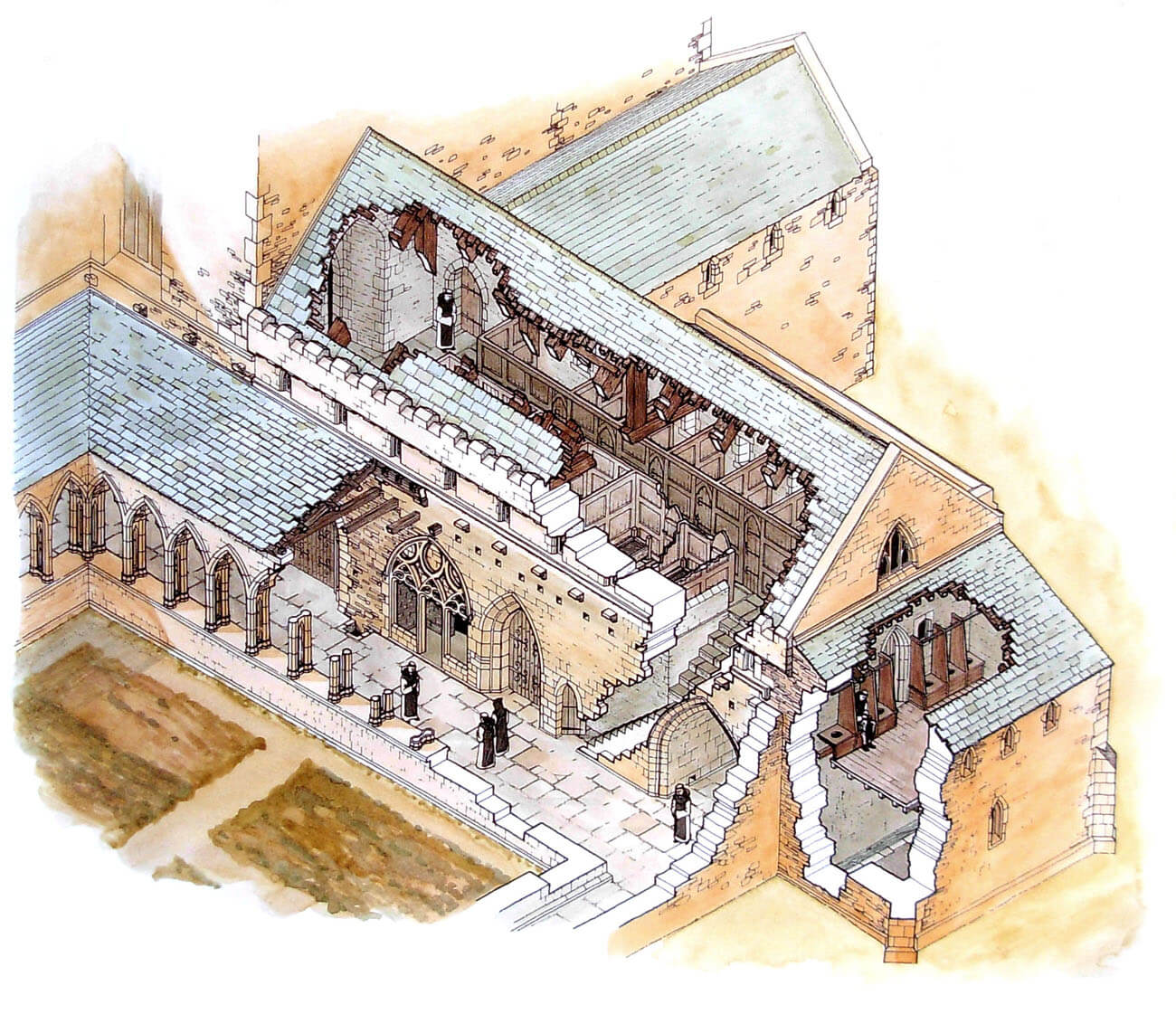

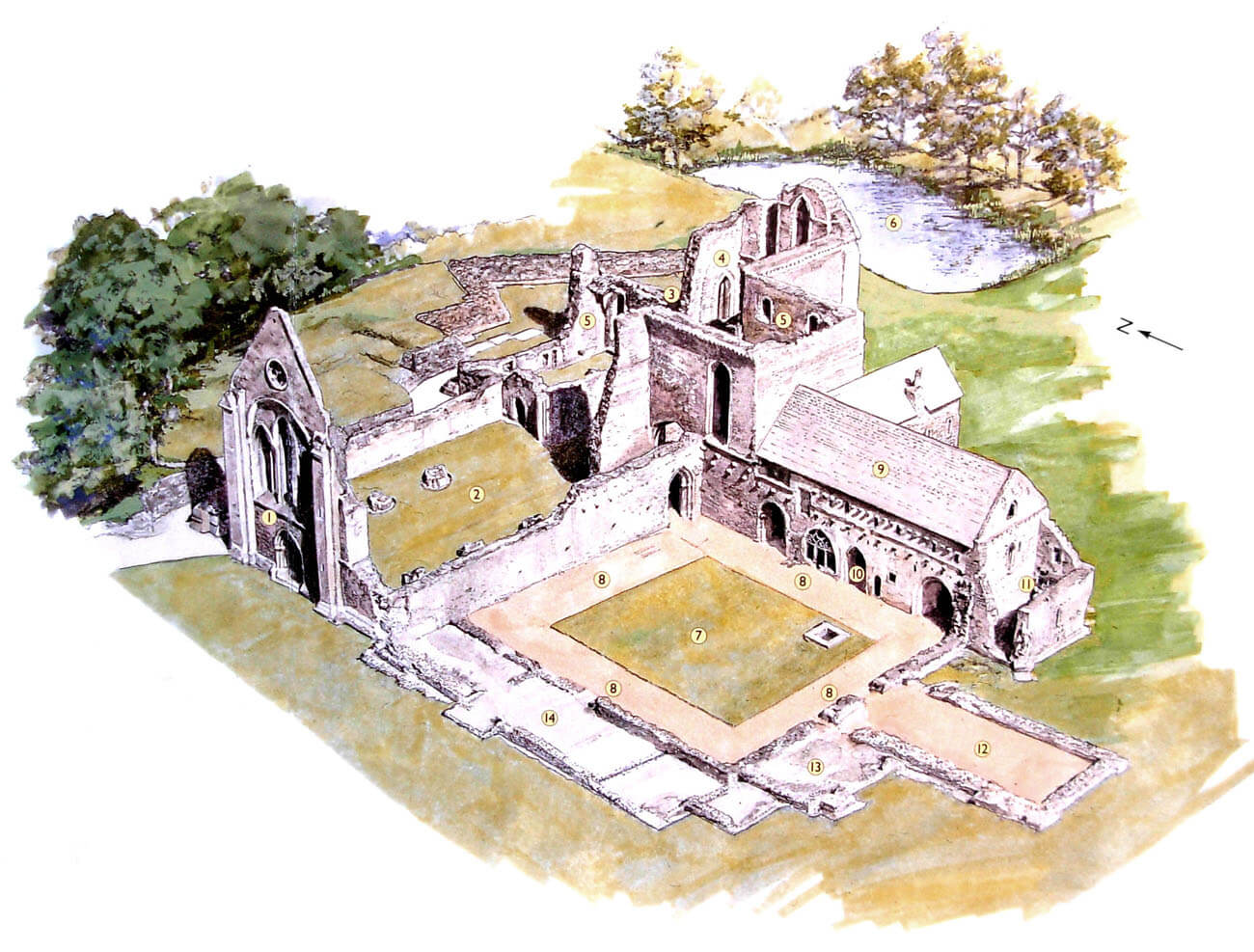

The abbey consisted of a church and buildings located south of it, which surrounded a square inner courtyard. Founded in the first half of the 13th century, the church was a structure orientated towards the parts of the world, raised on a Latin cross plan. It consisted of a three-aisle, five-bay nave in the form of a basilica, northern and southern arm of the transept, a low tower at the intersection of naves, chapels adjacent to the transepts from the east, and a short, quadrilateral chancel. The building plan was relatively modest, but in accordance with the recommendations of St. Bernard and Cistercian rule. By 1225, the eastern part of the church was completed and work on the transept began, after 1240 the foundations for the nave were laid. The main entrance to it was located in the west facade, divided by four pilaster strips: two in the corners of the aisles and two in the corners of the central nave. The middle entrance portal from the mid-thirteenth century received an ogival finial and rich decorations arranged in a toothed frieze. Above it, in a huge niche, was placed a triad of pointed windows with a central opening slightly higher than the side ones, and even higher cylindrical rosette with a delicate tracery, crowned by a Latin inscription commemorating Abbot Adam. Together with the change in building material, it indicates the transformation of the entire gable of the nave in the first half of the fourteenth century. The west façades of the aisles were pierced with single ogival windows, the north aisle additionally with an entrance portal, while a cylindrical staircase was inserted into the wall thickness of south aisle.

Inside, the nave of the church was not originally a large, free space. Between the five pillars of the northern aisle and four of the southern aisle, partition screens separated the central nave, in which stalls of lay brothers were placed. The extreme eastern bay of the southern aisle was fenced off in the second half of the 13th century even by a more solid wall (probably inserted after the fire, to strengthen the pier next to the tower), behind which on the northern side there was a choir of monks, closed from the west by a wall of the rood screen (pulpitum), and from the north and south by stalls of monks. The free space of the choir was directed only towards the presbytery, towards the main altar. The rood screen itself was a fairly solid and wide wall pierced in the middle with a portal and a stone staircase inside allowing access to its upper loft, where organs could be located in the later Middle Ages. Surrounded by many shafts, inter-nave pillars passed into ogival arcades over which ogival clerestorium windows were pierced. It was probably originally planned to crown the nave with vaults, but they were never completed. This intention is evidenced by shafts in the northern aisle, led from the floor to the height of the stringcourse under the windows. The aforementioned rood screen, which separated the nave intended for the lay brothers, from the choir and presbytery, where only monks could stay, in the fourteenth century was moved one bay east. Probably this was associated with a reduced number of monks who died of the plague. In the enlarged western part of the nave, two side altars were inserted.

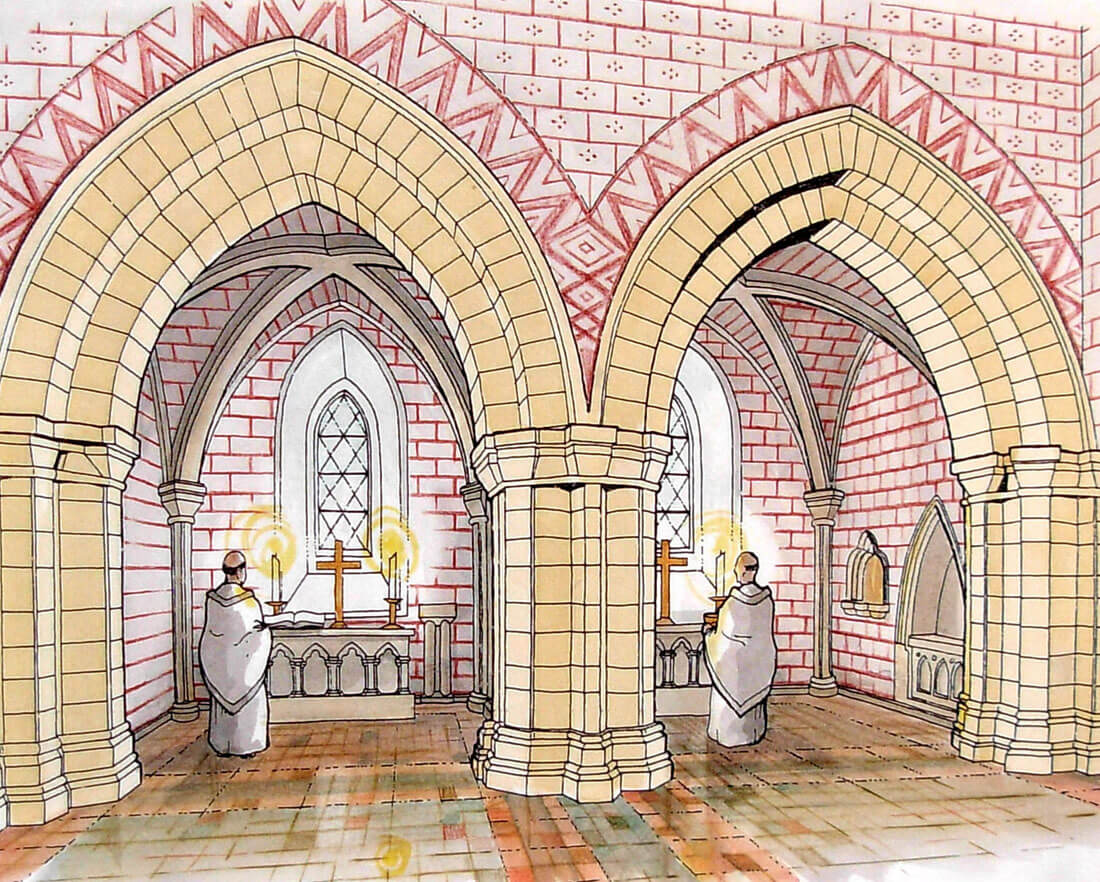

In the presbytery, the main altar was located on a low pedestal, occupying one (eastern) of two bays. Originally, it was planned to establish vaults above the presbytery, as evidenced by wall pillars in the eastern corners and in the central parts of the north and south walls, however, here too the church was eventually covered with a wooden truss. The eastern wall was pierced with three windows in the lower level and two in the upper and single tiny ones at the very top. Initially the middle lower window was higher, but it was almost leveled with others during reconstruction after the fire. Their jambs were then given richly decorated capitals and shafts, which distinguished them from other windows in the church, much simpler and less decorative (without capitals). On the outside, the eastern façade was divided by wide pilaster stripes, with the two corner ones forming a huge arch, which closed the entire façade from above, and the two middle ones constituted the base for the upper windows jambs.

The northern transept was accessible from three sides: through the aisle, northern portal from the side of the cloister cemetery and from the choir and presbytery. In its eastern part, as in the southern transept, there were two chapels. They were the only parts of the church that could be crowned with vaults, the others parts of the church were covered with a timber flat ceiling and an open roof truss. Each of the six chapels was illuminated by a single narrow ogival window, located above the altar. In addition, in the walls of the southern chapels there were niches topped with trefoils and stone niches for church vessels and as a place for a tomb. Similar niches and stone basins were also found in the southern wall of the presbytery and in one of the pillars. A staircase was inserted into the northern wall of the transept to allow access to the attic and the tower. On the opposite side, one portal led to the sacristy, while the other, placed about 3 meters above the floor, using night stairs, led to the dormitory, from where the brothers went to religious ceremonies at night. The southern elevation of the transept was crowned with three ogival windows in the gable part, the western elevation with a single large ogival window (decorated by a sophisticated tracery in the 15th century), and the eastern elevation with two small ogival windows located above the mono-pitched roof of the chapels. Later in the Middle Ages, the roofs of the chapels were raised and small rooms, accessible from the first floor of the eastern wing of the monastery, were added to the space above the rib vault. A staircase in the thickness of the southern wall of the presbytery led from these rooms to the attic above the eastern part of the church. During the reconstruction from the end of the 14th or the beginning of the 15th century, the entire church and the eastern wing of the abbey were raised and topped with a parapet based on protruding corbels.

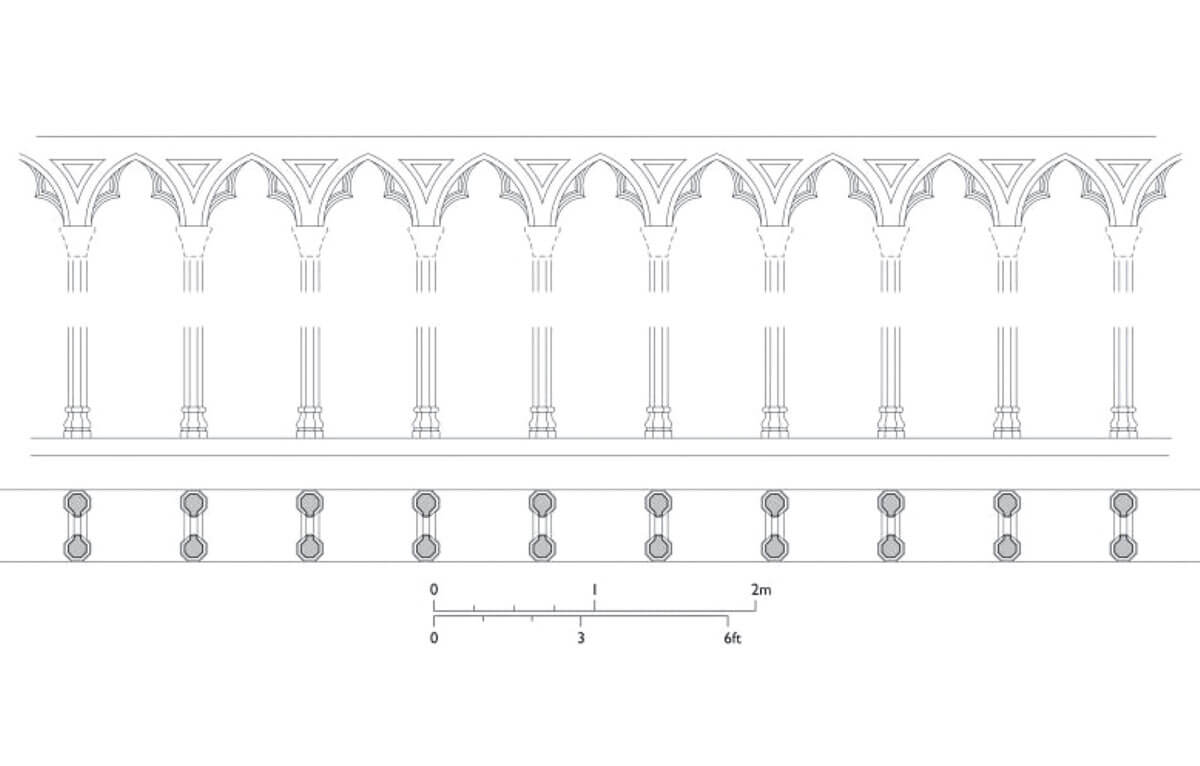

The inner courtyard (garth) measuring approximately 24 x 24 meters adjoining the nave from the south was surrounded by cloisters, which provided access to every wing in the monastery, and which was also a place of studying and reading books (the northern part of the cloister at the church). It were covered with mono-pitched roofs based on stone, pointed arcades, formed in the upper part in a trefoils and based on two rows of shafts, open to the garden of the inner courtyard (garth). In its south-eastern part there is a quadrilateral basin, which is a remnant of the lower part of a more extensive lavabo, that is a place to wash hands before meals.

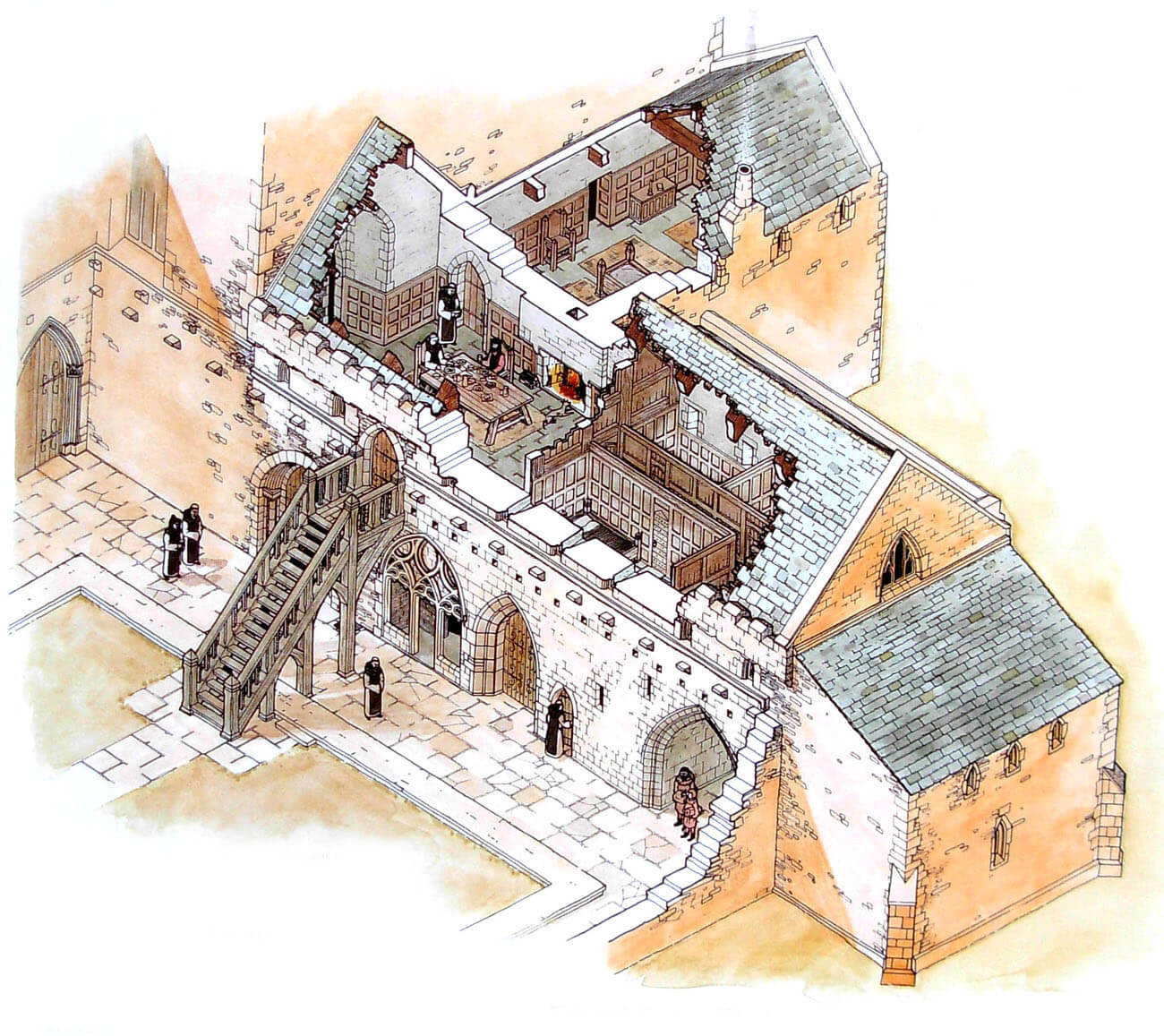

The eastern wing was created at the latest, around the mid-fourteenth century, but it replaced the earlier buildings, which were extended about 12 meters to the south. On the ground floor in the northern part there was a sacristy, covering the entire width of the southern transept. From the side of the cloister, the entrance to it led through a sophisticated semi-circular portal with carved capitals on the sides. The interior covered with a barrel vault was illuminated by a single ogival window from the east and an small southern window placed unusual at a slant due to the chapter house. To the south of the entrance to the sacristy, a wide niche was placed in the wall thickness, from the cloister side richly decorated with tracery with an interesting pattern similar to “daggers” (indicating construction in the mid-fourteenth century), with an entrance from both the chapter house and the cloister and two side windows. Its vaulted interior was used to store books and documents.

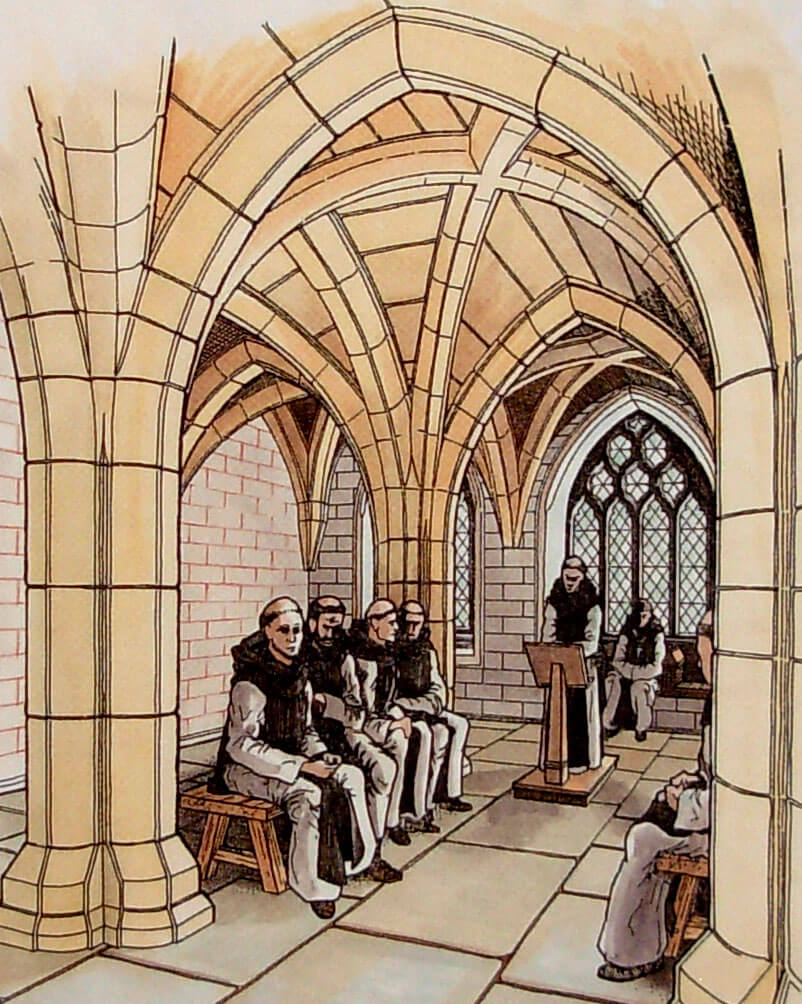

From the south, the sacristy in the ground floor was adjacent to the chapter house, a square room with a rib vault supported by four symmetrically arranged pillars. None of them had capitals, and the vault ribs fall directly to them and to the walls. The lighting was provided from the east by three large three-light ogival windows. Every day, monks gathered in benches along the walls to listen to the Cistercian rule, to confess their faults and receive punishments, as well as to deal with the matters of the abbey. In Cistercian chapter houses abbots were also often buried, as evidenced by three niches in the southern wall, perhaps originally housing tombs. In the south-west wall, there were stairs leading to the first floor, to the dormitory.

To the south of the chapter house, in the ground floor, there was a small passage and the latrine block at the end. The rib vaulted passage led outside the compact buildings, probably to the infirmary standing separately. Its vault ribs were based on corbels sculpted in the shape of female and male heads. The latrine block had two floors separated by a wooden ceiling. The latrines themselves were upstairs and the faeces fell into the stone channel at the north wall.

Initially, the entire floor of the east wing was occupied by the monks’ bedroom – the dormitory. It was connected through so-called night stairs with the church’s south transept to allow monks to quickly reach masses and with latrines on the opposite side. Originally, ordinary pallets lay along the walls, but in the later Middle Ages, an increased pressure on privacy caused them to be separated into two rows by wooden partition screens. In the 15th century, the northern part of the dormitory was rebuilt, transformed into an abbot’s hall, and the southern part into a pair of rooms for the most important guests. An external staircase was erected from the cloister side connected to a new ogival portal, and a fireplace was located in front of the entrance. The north-east corner on the upper floor of the east wing (above the sacristy) at that time housed the abbot’s private chamber, also heated by the fireplace (replaced in the 16th century by a new, much larger and decorated by 13th-century tombstone). Three small windows in the southern wall of the chamber were created in the thirteenth century, so it can be assumed that earlier it housed the prior’s chamber, who guarding order in the dormitory.

The southern wing from the mid-13th century was a one-story building, probably due to the wet and swampy ground in this area. From the west, it was occupied by a kitchen, then a perpendicular refectory and at the eastern end a small heated room for use in winter. As no traces of the hearth or fireplace were found, it is possible that it was heated only by means of portable braziers. According to another theory, this place was not occupied by the warming room, but by the so-called day stairs, leading to the first floor, to the dormitory. The refectory protruding southwards was a spacious room for dining. Its longitudinal walls have five holes each, the remains of posts supporting a wooden roof truss. In the thickened south-west part of the wall, a spiral staircase was additionally placed in the wall thickness, with an entrance decorated with a toothed frieze, leading to the pulpit from which it was read during meals. The kitchen was located in the corner between the west and south wing to be able to serve the main refectory and the refectory of lay brothers. In the 13th century it housed an open hearth in the middle of the eastern part, but after damage and fire it was rebuilt and separated into two rooms. After another fire at the beginning of the 15th century, during renovation, a large fireplace was inserted into its southern wall, protruding from the outside beyond the face of the wall.

In the western part of the abbey, on the first floor there was a dormitory for lay members of the convent, and later also for monks, as well as pantries and storage rooms on the ground floor. In the southern part, due to the proximity of the kitchen, there was probably a refectory of lay brothers, but it ceased to operate in the fourteenth century and was replaced by the office of the monk responsible for the monastery’s pantries. The middle part of the ground floor was occupied by the lay brothers’ living room, a place to rest during their free time. On the west side, two annexes were added to the wing, probably housing latrines, because under the day room, a stone channel ran across it. In the fourteenth century, an entrance porch was erected north of them.

Current state

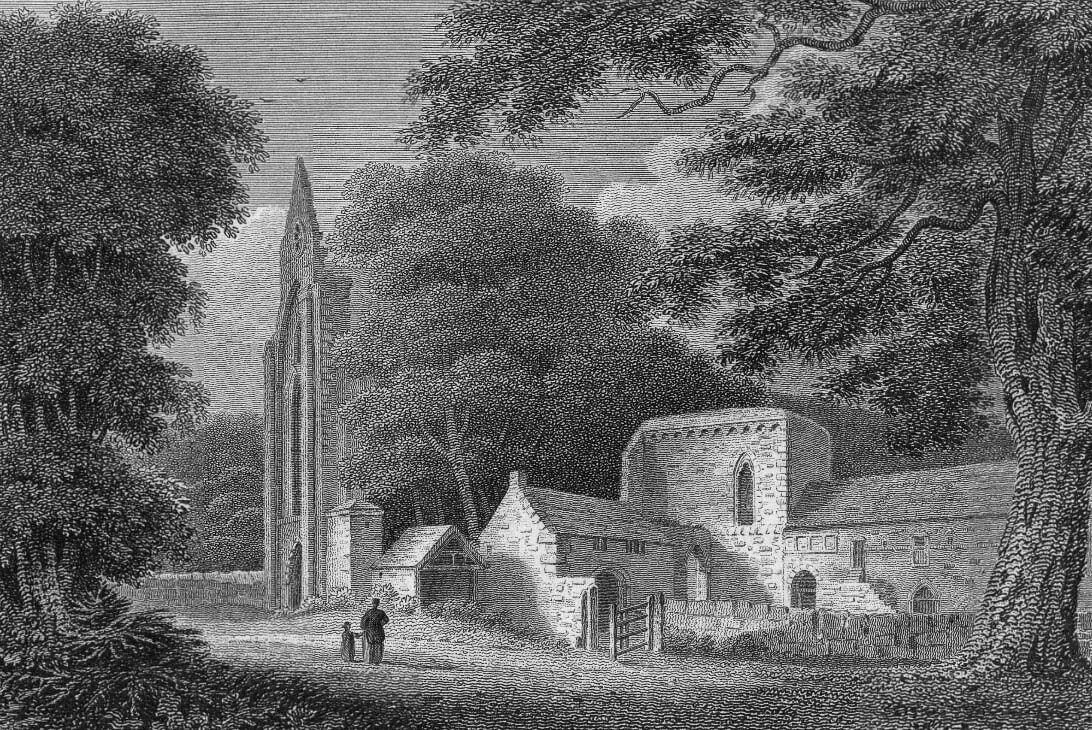

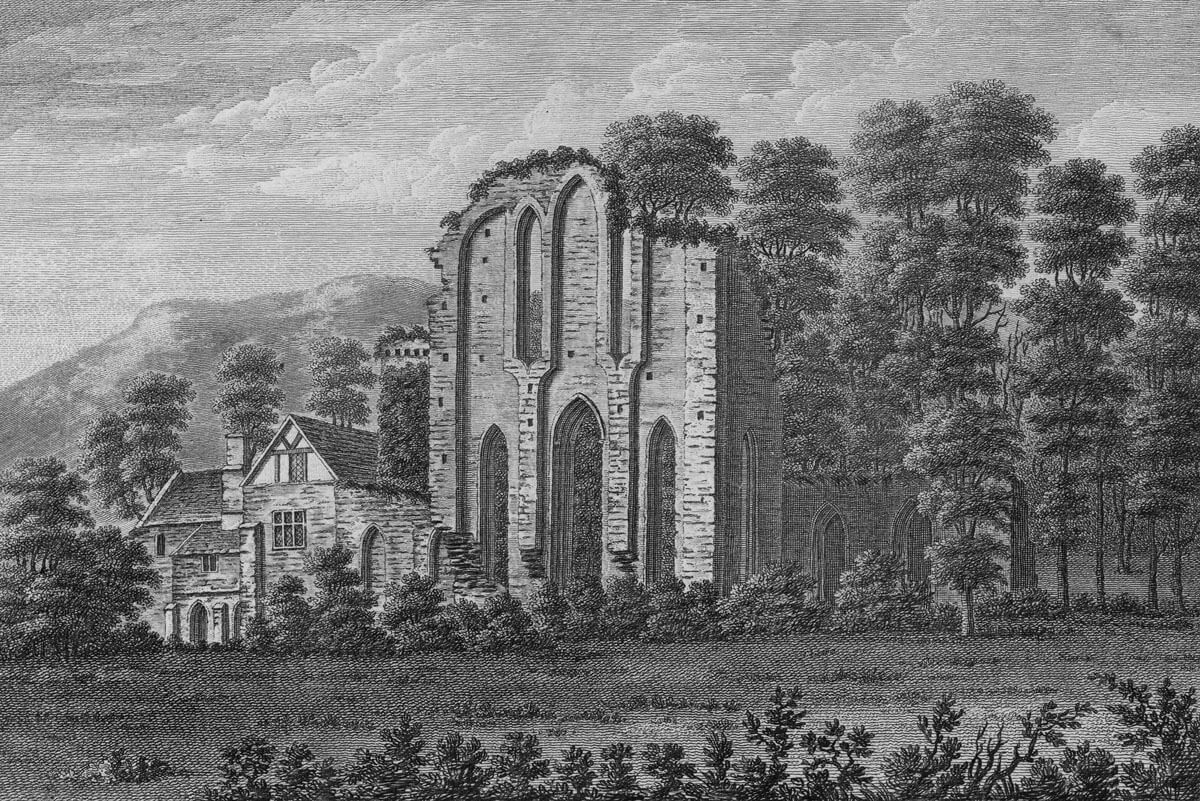

To this day, fragments of the abbey church have been preserved in Valle Crucis in the form of a magnificent western facade with an entrance portal, three Gothic windows and a rose window, the southern transept and the chancel. From the southern monastery buildings in the best condition, the eastern range has survived with the chapter house, the dormitory and later abbot’s chambers. The remaining buildings are testified only by the foundation parts high up to about 1 meter. Behind the buildings there is a monastic fish pond, apparently the only surviving fish pond in Wales. The abbey is open to visitors from March 24 to November 4, from Wednesday to Sunday from 10.00-17.00, entry on Monday and Tuesday is free.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Evans D.H., Valle Crucis Abbey, Cardiff 2008.

Harrison S., Robinson D.M., Cistercian Cloisters in England and Wales Part I: Essay, “Journal of the British Archaeological Association”, 159 (2006).

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals od Wales, Malvern 2012.