History

The beginnings of the Llanthony Priory date back to 1100, when according to tradition, the Norman knight William de Lacy, looking for a safe hiding place during the hunt, hid in a nearby chapel of St. David, and in return for saving, he vowed to build the church. Another version of the legend says that William lived here as a hermit with a priest named Ernisius, and they both expanded the already existing chapel of St. David. Soon, a temple dedicated to Saint John the Baptist was created. It was consecrated by Urban, Bishop of Llandaff and Hereford in 1108, and until 1118, a group of about 40 monks from England, founded the first monastery in Wales of canons regular, or Augustinians. It was supported by King Henry I and Queen Matilda, whom Ernisius was originally supposed to be a chaplain.

In 1135, after persistent attacks by the local Welsh population, the Augustinian monks fled the Black Mountains to Gloucester, where they founded a new priory called Llanthony Secunda. The situation for a return did not become favourable until 1171, when the Anglo-Normans conquered Ireland, and Hugh de Lacy and his son Walter were endowed with numerous lands, some of which they gave to the monasteries of Llanthony Prima and Llanthony Secunda. Around 1186, Hugh de Lacy transferred the income to the abandoned priory, but rebuilding probably did not begin until after the death in 1189 of Prior Roger of Norwich, who, according to the chronicler Gerald of Wales, despoiled the monastery’s property. In 1205, the priory church was still far from complete, as the income from Duleek church in County Meath was used to continue its work. The rebuilding of Llanthony was finally completed around 1230-1240. As early as 1242 the brethren of Llanthony Prima were able to provide shelter to the Bishop of Armagh, Albert Suerbeer, who recorded fond memories of his stay during journey.

In the second half of the 13th century some financial problems had to occur in the priory, because in 1276 it was put under royal custody. Moreover, the brothers fell into a series of disputes with local marcher lords, which even led to the armed seizure of their property in Oldcastle and Redcastle in 1279 by Thomas de Verdun, Lord of Ewyas. He was also involved in wounding the prior and the murder of two monks, and twenty years later another marcher lord, Gilbert de Bohun, took a large number of monastery animals and goods. In 1284 financial problems worsened due to the Welsh war campaigns of Edward I. Moreover, there was a decline in discipline, criticized during the control of Archbishop Pecham of Canterbury.

In 1291, Llanthony Prima had a fairly high annual income of £ 160, but as early as the fourteenth century sources often reported information about internal problems. In 1348 the priory was again placed under royal supervision, and in 1354 a certain Thomas de Crudewell escaped from the monastery. In the 70s of the fourteenth century, Prior Nicholas Trinley was brutally beaten by his brothers, allegedly for bad leadership of the community, and had to flee to Llanthony Secunda. Interestingly, papal pardon was soon issued for the perpetrators of the beating and murder of one of the brothers, and one of the participants in the incidents, John de Wellyngton, even became prior. In turn, in 1386 Prior John de Yatton was temporarily arrested, due to the inefficient collection of tithes and royal taxes.

Despite the above problems Llanthony flourished during the entire thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and only in the fifteenth century, it began to decline. During Owain Glyndŵr’s Welsh uprising, the Llanthony community was accused of helping the rebels and devastated by the royal troops. Admittedly, the union with Llanthony Secunda brought short-term improvement in 1481, but it had to be paid with the sum of 400 marks to King Edward IV. End occurred in 1538 when the monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII. The monastery buildings were sold for 160 pounds, but unused and unrepaired by new owners, began to fall into disrepair. Only the infirmary was transformed in the 18th century into the parish church of St. David. In 1799, the estate was bought by Colonel Mark Wood, who transformed some buildings into a house and shooting range.

Architecture

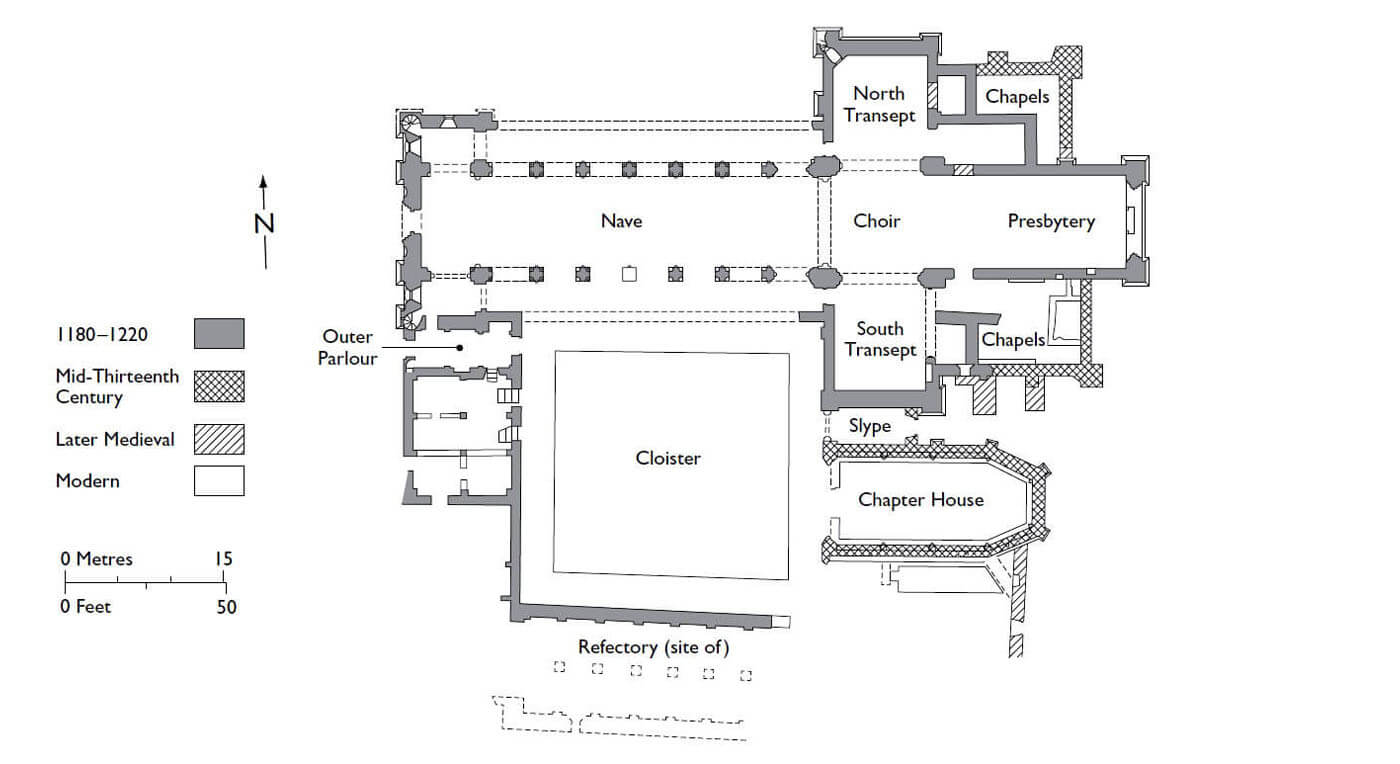

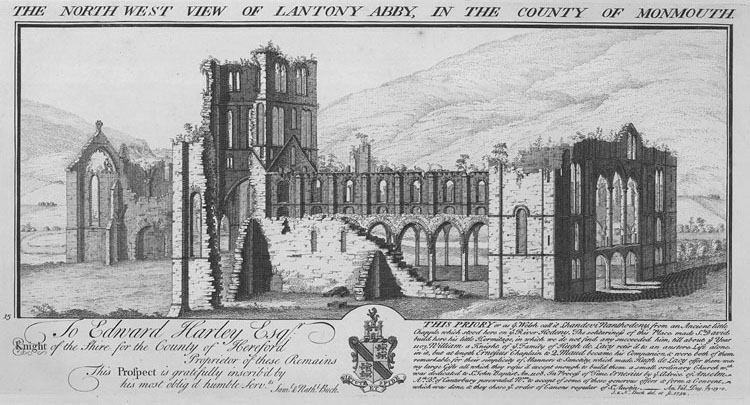

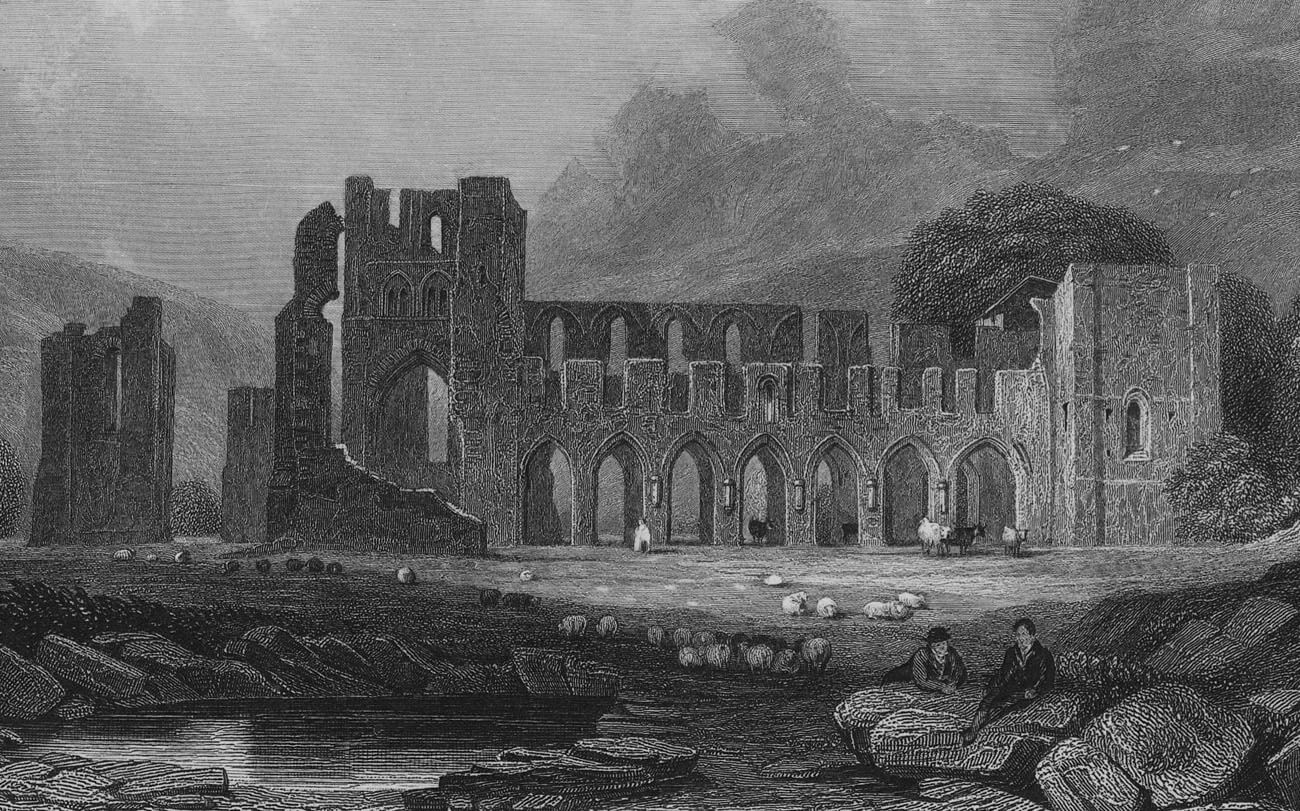

Llanthony was founded in the secluded Ewyas Valley, amidst the bare peaks and hills of the eastern Black Mountains. It was situated on the eastern side of the Honddu River, which flowed through the valley in numerous meanders, and among the numerous smaller streams flowing down from the mountains to the east. The high, steep-sloping hills provided isolation, while the river and streams provided a source of fresh water and fertile land at the bottom of the valley. The priory was built on gently sloping, undulating terrain. It consisted of a Romanesque-Gothic church on the north side and the buildings of the monastic claustrum to the south. At a distance, on the south side, there was an infirmary with a chapel, and economic buildings on the west side, located closer to the trail running through the valley. On the west side, there may also have been a late Gothic residence of the prior, consisting of two perpendicular wings. The entire monastery complex was surrounded by a wall with an entrance gate on the west side, from the beginning of the 14th century in the form of a gatehouse with a wide passage on the ground floor and a room heated by a fireplace on the first floor.

The priory church was built of red sandstone, partly ashlar, partly unworked, on a Latin cross plan in the form of a seven-bay basilica (eight-bay in the central nave), with an impressive central tower above the crossing, a pair of smaller quadrangular western towers and a chancel on a rectangular plan, significantly elongated, which was a typical solution in monastery churches that had to accommodate the monks’ stalls. In addition, side chapels were added to both arms of the transept, and to the sides of the chancel, significantly expanded and enlarged in the mid-13th century. In the older eastern part of the church from the fourth quarter of the 12th century, round Romanesque arches were used, while in the western part pointed arches that were created, when the Early English Gothic at the beginning of the 13th century began to dominate. The chancel was therefore built first, and then the builders gradually moved west, finally creating a building with an internal length of 64 meters.

From the outside, the vertical division of the church elevation and at the same time the reinforcement of its walls were provided by pilaster buttresses, especially massive in the corners of the western towers, the transept and the chancel. Some of them, such as the two western and north-western at the transept, housed spiral staircases in the thickness of the walls. The horizontal division of the church elevation was provided by numerous cornices: base cornices, drip cornices under the window sills, string-course cornices dividing the storeys of all the towers, or crowning cornices. The oldest windows in the chancel and transept were in the form of tall, narrow openings with semicircular heads. The eastern wall of the chancel may have originally been pierced by a triad of such openings, but in the 14th century a huge pointed tracery window was inserted there, filling almost the entire space between the buttresses. The nave was already lit by windows with slightly pointed arches, heralding the coming Gothic style. Changing tastes were especially visible in the central tower, whose windows on the highest storey were early Gothic lancets with flanking columns and capitals on which external archivolts were mounted, while the lower storeys were still lit by stepped semicircular openings of the Romanesque tradition.

In the western façade of the church, a triad of very tall lancets lit the central nave from the west. It were slightly set back, giving the central part of the elevation a modelled character in contrast to the surrounding flat surfaces. Above them were smaller attic windows, and below them were three pointed entrance portals. Interestingly, semicircular, moulded windows were placed on the middle storey of the western towers, above which high recesses of blind arcades were created in the western façade with already lancet heads carried by the capitals of the wall columns. The whole created a coherent, impressive composition, covered with an ashlar face, with stonework smooth enough to highlight the blind arcades, which were the main form of decoration of the church façade. Sculpture was not allowed anywhere, so vertical rollers and horizontal cornices, which outlined almost every element, gained extraordinary strength and integrated massive pilasters with the surface of the walls.

The interior of the nave was characterized by very narrow aisles, separated from the central nave by pointed arcades on cross pillars. Almost every arcade, including the pillars, was moulded along its entire height with a chamfered groove on the sides, in which there was a shaft ending with a rounded base and a quadrangular low plinth. As a result, a single pillar had four shafts, one in each corner. The arcades of the extreme eastern bay of the nave stood out, created similarly to the arcades under the tower, with multiple chamfering of the archivolts separated by grooves. This difference could have resulted from the extension of the Augustinian stalls also to the eastern bay of the central nave. The lower part of the central nave, up to the height of the cornice above the archivolts of the arcades, was made of ashlars. Above, the triforium and clerestory was built of unworked stone. The aforementioned cornice was intersected by short and clustered shafts, with heads covered with motifs of so-called trumped-scallops, at the expense of experimenting with more progressive plant motifs, which was reminiscent of solutions from the Glastonbury Abbey. Equally between each shaft group there was a two-light, moulded with rollers opening with lancet heads. The highest level consisted of clerestory windows, connected by niches with triforium openings, also in a way characteristic of Glastonbury. At this level, a gallery ran through the thickness of the wall.

The transept was vaulted in two bays, one for each arm, on slender corner shafts with trumped-scallop capitals. The central tower was divided into three upper floors, the lowest of which was originally covered from the outside by the roofs of the nave, transept and chancel. In the ground floor, the tower opened on all four sides with high, pointed, multi-chamfered arcades. In their arches ribs were placed, set on corbels with simple plant decoration and on groups of three short shafts, each of which had its own head in the trumped-scallop type, but a common moulded abacus. The arcades on the east-west axis were distinguished by additional pilasters, supported by moulded, very wide consoles. Below, the under-tower pillars were smooth, decorated only with moulding of the corners, probably due to the benches placed there – Augustinian sedillia, reaching the height of the corbels on the pilasters. Behind them, the interior of the chancel was covered with a vault supported by bundles of shafts, reaching the plinths on the floor and intersecting the under-window cornice. As in other parts of the church, the capitals in the chancel were decorated with trumped-scallop motifs.

To the south of the nave of the church stretched a square garth with sides about 27 meters long. The claustrum had a traditional three-winged layout, with the eastern wing extending the southern arm of the transept, and the western wing on the line of the western façade of the church. The two above wings were connected by the southern wing. The entire claustrum at ground level was traditionally connected by roofed cloister, which protected against bad weather, while also being a place of study, contemplation, or the performance of processions or certain ceremonies. The spacious, open space of the garth could be used for gardens, a herbarium and a well with fresh water.

The western wing was probably filled with rooms for the monastery pantry and storerooms (cellarium). It is known that the church was directly adjacent to a three-bay passage or outer parlour of the monastery, covered with a cross-rib vault and accessible from the outside by a portal with a trefoil head and handsome moulding. This popular Gothic motif was not used anywhere else in the monastery church, which would indicate that the western wing was built somewhat later. Further to the south, there was a hall covered with a cross-rib vault supported by two quadrangular pillars with chamfered corners and two wall half-pillars. The room was lit by two-light lancet openings. Then, the wing contained one or two more rooms on the ground floor and more rooms on the first floor, probably intended for lay brothers or novices.

The south wing traditionally housed the refectory, in Llanthony in the form of a two-aisled, vaulted hall, with two bays deep and seven bays long, with the longer axis parallel to the longitudinal axis of the priory church. There was probably a kitchen next to the refectory, placed next to the west wing, so that it could also serve the lay brothers. On the eastern side of the refectory there may have been a small room, containing either a passage leading to the southern part of the monastery or a calefactory room, the only room heated in the winter apart from the kitchen.

A chapter house was built in the east wing around the mid-13th century. It was a vaulted room with a three-sided end to the east, where the monks gathered daily for meetings under the chairmanship of the prior, sitting on stone benches placed around the walls. The entrance to the chapter house led from the cloister through a richly decorated portal flanked by two openings. The portal had a stepped form, with columns set on round bases and with capitals decorated with plant motifs. Inside, the vault rested on shafts grouped in threes, between which slightly recessed lancet windows were set. From the outside, the chapter house walls were reinforced by buttresses. On the north side it was adjacent to a two-bay passage leading to the monastery grounds, accessible from the cloister by a pointed portal, with a wide chamfer and a narrow shaft in the archivolt and three free-standing columns in the jamb. The passage was covered with a cross-rib vault, supported by very short shafts with trumped-scallop capitals and polygonal abacuses. To the south of the chapter house there was a room accessible through a richly decorated portal, perhaps a books room or a day room. The upper floor of the east wing must have been used as a dormitory.

Current state

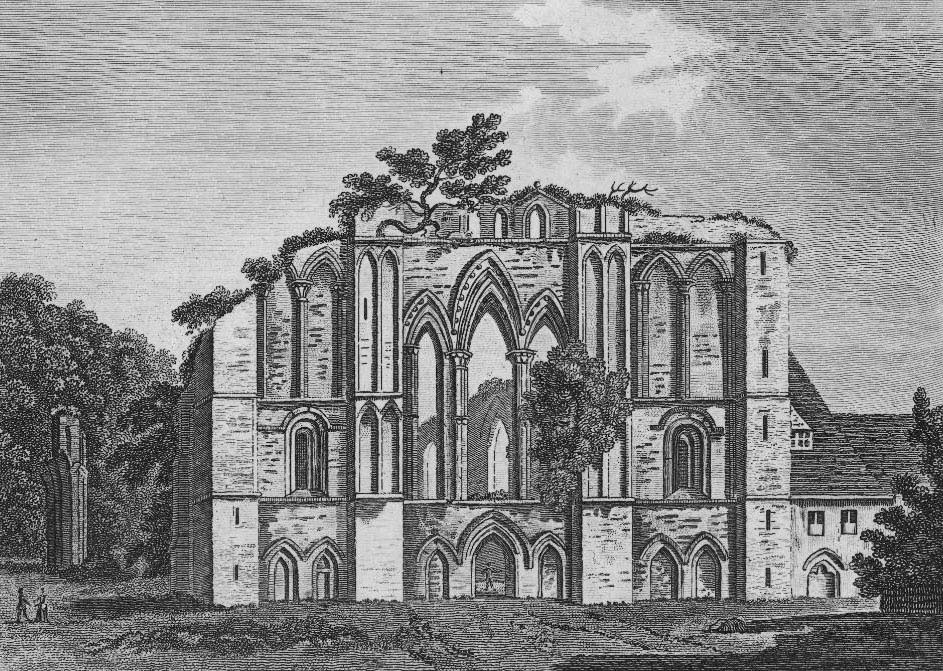

In Llanthony, the ruins of the priory church, the remains of the former claustrum, the utility building converted from the former gatehouse and the parish church, i.e. the former monastic infirmary, have survived. Of the church two walls of the central tower are without the highest storey, the western towers of full height but without the connecting wall of the façade, part of the inter-nave pillars, the northern wall of the central nave to the level of the triforium, the ruined chancel and relics of the transept (the northern one has been reduced to the ground floor except for one corner, the southern one has almost the entire gable wall). Most of the church is unroofed today, but one vaulted bay has survived in the northern aisle. It is also worth paying attention to the architectural details in the transept and at the crossing or to the inter-nave arcades. In the western part, the handsome elevations of the towers of the former façade still look impressive.

The claustrum consists primarily of the remains of the eastern wing with a ruined chapter house and a still vaulted passage on its northern side. In addition, fragments of the ground floor of the western wing are hidden in the modern hotel building, which currently operates at the priory. The height of the original building is visible on the elevation of the southern tower of the church. The southern wing is visible to the naked eye only in the form of a wall from the side of the unpreserved cloister, on which from the outside, i.e. from the side of the former interior of the refectory, the remains of the wall arcades are visible. The parish church, i.e. the former infirmary, today has transformed windows and an early modern porch, but the bricked-up 14th-century northern portal and the 14th-century chancel arcade of the chapel have survived.

The ruins of Llanthony Prima are now under the care of Cadw, a government agency. They are open all year round except Christmas and New Year’s Day, from 10am to 4pm, with the last admission being 30 minutes before closing time. Entry to the priory is free to all visitors. Part of the priory buildings, which have been rebuilt in early modern times and then renovated, now function as a hotel (occupying the former west wing and presumed prior’s residence). The adjacent infirmary is now the parish church of St David, but the interior of the former gatehouse is not open to the public.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.