History

The origins of Tregrug Castle, originally a small Anglo-Norman motte of wood and earth, controlling the lands between Usk and Caerleon, date back to the first half of the 13th century, when the Welsh commote Tref-y-Grüg passed into the hands of the de Clare family. Construction of a stone castle began on a new site, possibly in the second half of the 13th century, probably at the initiative of Bogo de Clare, the third son of Richard de Clare, who received the local estates in the 1280s from his brother, Earl Gilbert II de Clare. It is also possibly, that works began a dozen or so years earlier at the initiative of Earl Gilbert himself, although he was already involved in the construction of Caerphilly Castle. One of the first direct records of the castle was information about the royal garrison being maintained there in the years 1262-1263, but it is not known whether this concerned the older wooden structure or the stone castle.

Bogo often stayed at Llangybi before his death without issue in 1294. A year later, Earl Gilbert died, while his heir, Gilbert III, was still a minor. Countess Joan took over the care of her son and the castle “Tregruk alias Treigruk” until 1307. This was a period when fighting with the rebels of Madog ap Llywelyn was ongoing in Wales since 1294. During this time, the castle must have been damaged, because from 1301 to 1306 repairs were recorded to the roof of the tower, hall, stables, kitchens and bakery. In addition, between 1303 and 1304 two masons were paid to block a breach in the wall. The construction work was probably not completed in 1314, when Gilbert III de Clare was killed in the battle with the Scots at Bannockburn. His widow, Matilda, was allowed to retain the lordship. It is likely that she continued to work on extending or completing the castle, as evidenced by documents from 1315-16 referring to a gatehouse and portcullis, and documents from 1319-1320 mentioning a small hall. There is also a record of a tower being built, to be roofed with two thousand tiles in 1321. By then, Matidla was dead, and the de Clare estates were divided between Gilbert III’s three sisters. The lordship of Usk passed to Elisabeth and her husband Roger Damory. One of the couple’s first decisions was to strengthen the castle’s defences by building some unknown wooden fortifications, possibly hoardings. The most feared figure was probably the infamous favourite of King Edward II, Hugh Despenser, who had taken over the Glamorgan region through his marriage to another of Gilbert’s daughters.

In 1321, Roger Damory joined the barons’ conspiracy against the unpopular Despenser. After initial successes, the rebels lost the Battle of Boroughbridge, and Damory was charged with treason, though he died of wounds prior to his sentence. Elisabeth and her children were imprisoned and forced to handing over their property. She regained her inheritance only after the fall and death of Despenser in 1326, when a new king, Edward III, ascended the throne. Despite the fact that her favorite seat was Usk, she often stayed in Llangybi, certainly carrying out the necessary repairs and modernizations in the castle until her death in 1360. In the following years, Tregrug probably fell into decline, but it was inhabited, among others, by a branch of the Mortimer family, who owned the castle due to their marital affinities. It is not known what was fate of the castle during the last Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr at the beginning of the 15th century. It was not recorded either in the 1398 division of the estate following Roger Mortimer’s death, or in the 1424 survey of Edmund Mortimer. The local lands passed to the Crown in 1461, when the Mortimer heir, Edward, Earl of March, was recognised as King Edward IV.

In 1555 the castle and its estate were sold to the Williams family of Usk. If the new owners lived in the castle, it was only for a short time, until a more comfortable early modern residence could be built. During the English Civil War the ruined structure was refortified and held by the Royalist Sir Trevor Williams, who brought a garrison of sixty men to Tregrug. Cromwellian Colonel Thomas Saunders is said to have prepared to capture him, but there is no record of any fighting taking place for the castle. As a result of the defeat of the King’s supporters, Tregrug was supposedly destroyed and slightened by order of Parliament at the end of the war, for fear of reuse for military purposes. It is likely that this damaged the keep, but the rest of the old castle was abandoned without any deliberate destruction.

Architecture

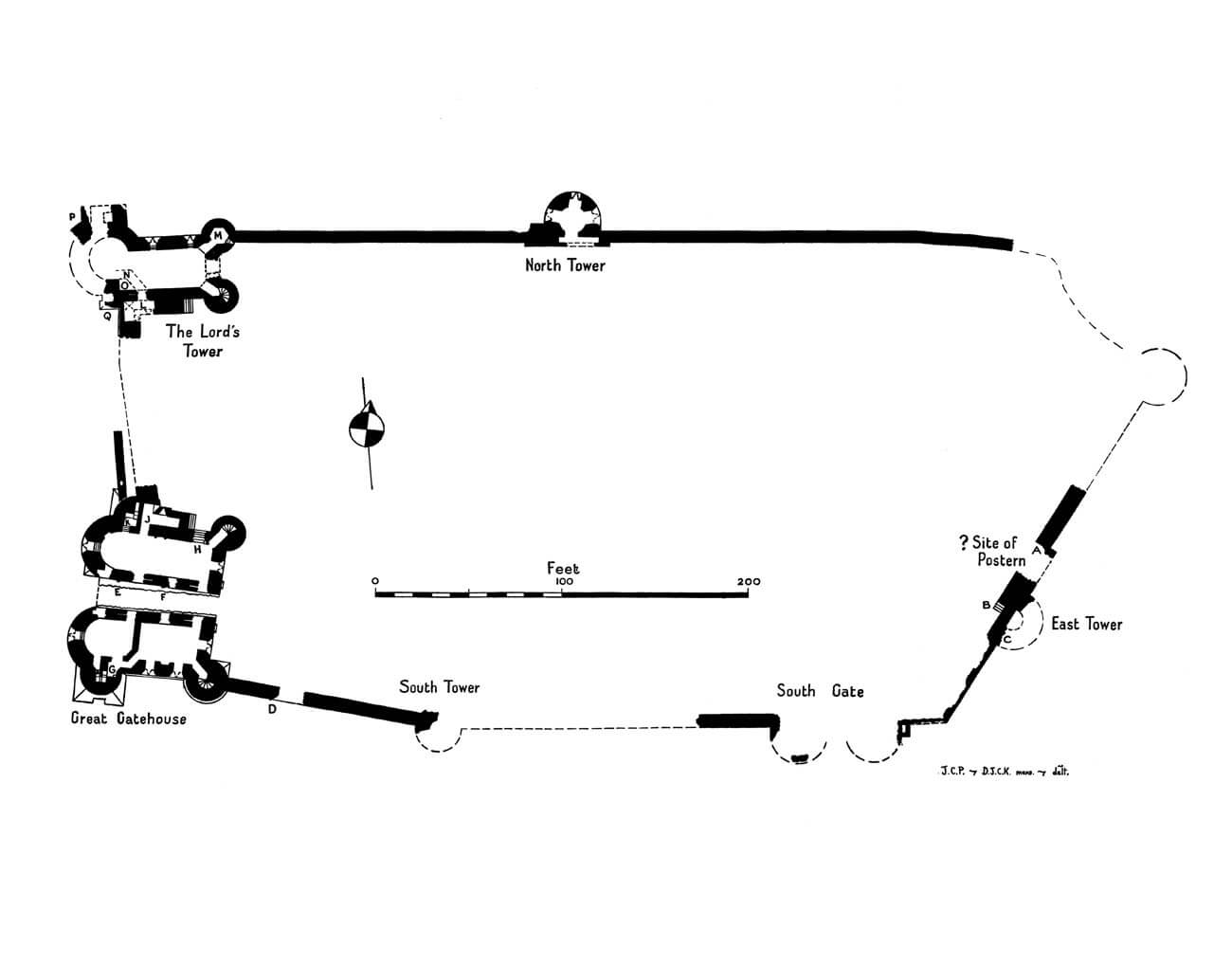

Tregrug Castle was built on a large hill, between two streams running parallel in narrow valleys to the north and south, and then joining the River Usk in a wide flood valley to the east, where an older wooden castle had originally been located on a small hill. The topography protected Tregrug with high and fairly steep slopes to the north, east and south, while a more convenient approach was only from the saddle to the west. The castle filled most of the hill’s summit, consisting of a huge courtyard surrounded by a defensive wall, one of the largest in Britain. It was laid out on an elongated pentagonal plan measuring 160 x 80 metres. The builders’ intention was clearly to cover the entire extensive summit of the hill, so that the natural conditions of the terrain would protect the castle on all sides.

The castle was built of yellowish unworked limestone and red sandstone ashlars. The defensive wall was massive, but not very high, because in the northern part of the perimeter it was about 1.9-2 meters thick at the ground level and only about 6 meters high to the level of the wall-walk. It was probably more high in the more endangered western section, where its thickness reached even 3 meters. The southern and eastern curtains were about 2 to 2.6 meters thick. At the base of the curtain it was reinforced with a batter, typical of Anglo-Norman architecture. Above, quite a few putlog holes were left in the elevations from the scaffolding used during construction. The wall-walk ran in the crown, which due to the considerable thickness of the wall did not need to be widened with a wooden porch. The protection of the guards on duty there was most likely provided by a crenellated parapet. On the western side, the castle was also protected by a wide moat, partially carved in the rock, perhaps turning into a narrow ditch on the less endangered sections of the perimeter.

The perimeter of the wall was reinforced by a keep in the north-west corner, an impressive gate complex on the west and several round and semicircular towers on the other sides. One, probably of a horseshoe shape with a diameter of 7.6 meters and a wall thickness of 2.1 meters, was located on the southern section. Another with a diameter of 9.4 meters and a wall thickness of 2.4 meters was located on the northern side, where a fragment of the thickened curtain from the outside and from the inside on both sides could have housed stairs. A very similar tower with a diameter of 9.7 meters and a wall thickness of 3.1 meters was located on the south-east section. The tower may have also protected the north-east corner. In addition, in the eastern part of the southern curtain there were two semicircular towers, between which there was a second gate, less impressive than the main entrance. The defense was supplemented by at least one bartizan, suspended at the wall in the south-west part of the perimeter. All defensive works were placed at fairly regular intervals from the south and east, while from the north, where rocky escarpments provided sufficient protection, long curtains were secured by only one tower. The most vulnerable western part of the castle was the best protected, distinguished by a massive gate and a keep.

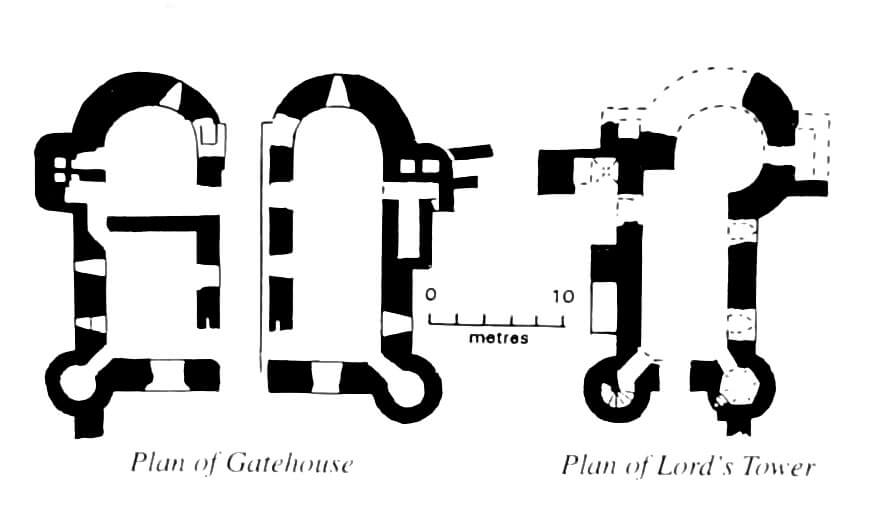

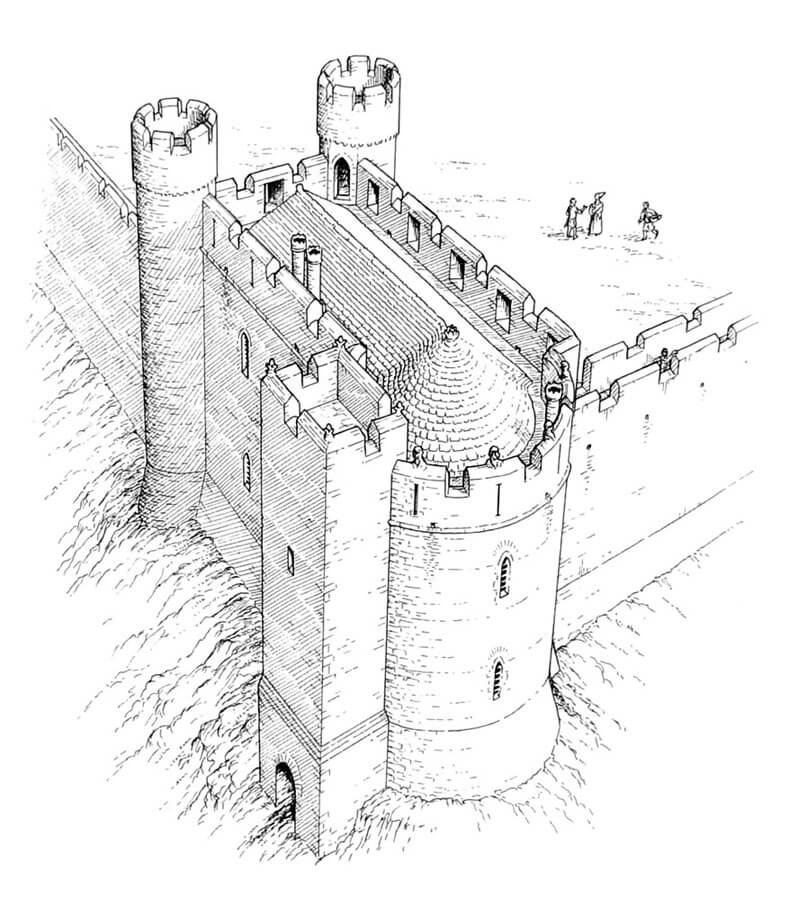

The entrance to the castle was through an Edwardian gate situated in the south-west corner, consisting of two horseshoe-shaped, strongly elongated towers with walls up to 3 metres thick, flanking the centrally located passage and connecting above the ground floor, where it formed a single mass of building measuring approximately 25 x 24 metres (it was larger than the gatehouses at castles such as Harlech, Caerphilly, Llansteffan, or Tonbridge, and only slightly smaller than the royal Beaumaris). On the inside, the gate had two cylindrical communication turrets, and on the sides (from the north and south) semicircular projections containing latrines. The whole was clasped at the base by a batter, most developed at the southern projection. The gate passage was protected by at least two sets of wooden gates and portcullises at both ends, thanks to which the building was an independent defensive work. It is possible that there was a third portcullis in the middle, and the side entrance from the courtyard to the northern tower was also closed with a lowered grate and door. The entrance was also closed after raising the drawbridge, the rear part of which fell down. Deeper inside the passage was a wooden floor covering the remaining part of the pit, dismantled in case of danger. The ground floor of the towers housed guard rooms, providing access to the loop holes, of which the northern chamber was heated by a fireplace. On the first floor, in addition to the mechanism operating the portcullis and the drawbridge, there were living quarters, equipped with fireplaces and latrines. The latter were exceptionally numerous by medieval standards, and were also placed in the least luxurious rooms on the ground floor. In at least two of them there was even a stone bowl for washing hands, and next to it a flat stone shelf, perhaps intended for towels, jugs or other toiletries. The first floor could have served the castle garrison, while the second floor, probably larger and with a higher standard of living, as in other buildings of this type, could have been intended for more distinguished residents.

The keep located in the north-west part of the castle, due to its location and asymmetrical shape, was a unique structure. Rectangular in plan, with longer sides on the east-west line measuring 10.4 meters, with two turrets in the eastern corners, it had a rounded front facing west, with the form of a tower incorporated into the building. This tower was 3/4 cylindrical, with a diameter of about 12 meters, additionally equipped with a quadrangular projection or turret on the north side, probably housing latrines. The second quadrangular annex adjoined from the south. The eastern turrets flanked the entrance portal, equipped with a portcullis and a hole for the door bar. The south-eastern turret housed a spiral staircase, while the north-eastern turret housed a small hexagonal chamber, probably intended for a guard overseeing the courtyard in front of the entrance through a loop hole. The southern annex on the ground floor contained a small but ornately furnished room, covered with a cross vault with chamfered ribs and bas-relief corbels. The main part of the keep was filled on the ground floor by a large hall measuring 13 x 6.4 meters, with a circular niche created in the western part. The layout of the upper floors was probably similar, but it were certainly more luxuriously equipped with fireplaces, latrines, or wall shelves.

Current state

Tregrug is probably the largest of the currently forgotten and neglected castles in Wales. Until now, fragments of the western gatehouse, the southern tower of which is 5 meters high, fragments of the perimeter walls 1 to 5 meters high, and the relics of the keep have survived from the once magnificent building. The whole area is densely covered with vegetation and requires cleaning and renovation works. A few hundred meters to the east is the mound of the first Llangybi castle, situated just behind the Fisherman Cottage farm.

bibliography:

Davis P.R., Forgotten Castles of Wales and the Marches, Eardisley 2021.

King D.J.C., Perks J.C., Llangibby Castle, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 105/1956.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.