History

The bishop’s castle in Llandaff was erected in the second half of the thirteenth century, probably on the initiative of Bishop William de Broase, managing the diocese in the years 1266 – 1287. This would be evidenced by the great similarity of the gate of Llandaff Castle with the main gate of the stronghold in Cearphilly (erected around 1277), which the bishop, as a member of a powerful family, must have seen.

After the death of Bishop William in 1287, there was a vacancy period in the diocese of Llandaff until 1297, during which the income from church goods was derived by Earl Gilbert de Clare (builder of Caerphilly and Morlais castles). Then John of Monmouth took the office of bishop, who remained in office until 1323. Sometimes he was credited with founding Llandaff Castle, which seems unlikely, since John was a theologian, a former chancellor of Oxford University, unknown to any other building foundation, as was his successor, the Dominican John of Eaglescliffe. During the office of the latter, in 1328, the castle was recorded in written sources for the first time in history.

At the beginning of the 15th century, according to early modern tradition, the castle was to be destroyed during the Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr. However, it probably did not happen, because no sources contemporaneous with these events have confirmed the sieges and fights. Bishops were in Llandaff until at least the middle of the 15th century. It is known that in 1448 Bishop Nicholas Ashby issued a lease document at the castle. Only in the following years the castle fell into neglect when successive bishops began to prefer their seat in Matharn near Chepstow.

In the 16th century, the castle was leased by the bishops of Llandaff to the family of Mathew of Radyr. In the time of Bishop Anthony Kithin, they had already obtained the right to free possession of the castle, which probably influenced the decision of the owners to carry out major renovation works in the second half of the 16th century. When in 1596 the building was taken by Edmond Mathew, the castle was still in such good condition that it could provide refuge to the escapees from the conflict between Edmond and his rival Edward Lewis with Van. The castle began to deteriorate at the beginning of the 17th century due to the debts and troubles of Edmond Mathew, and then the emigration of his son George to Ireland. For this reason, the castle was sold in 1613. Although at the end of the 17th century it was leased, at the latest in the second half of the 18th century it was already in a state of advanced ruin.

Architecture

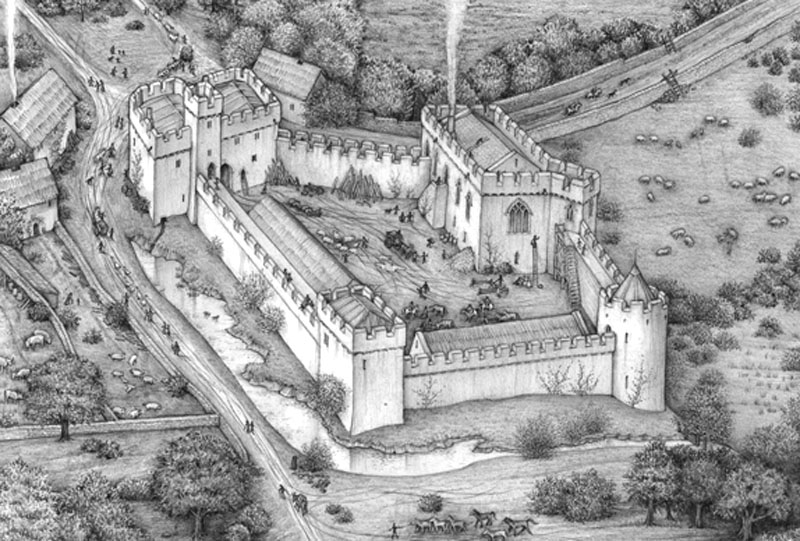

The castle was situated south of the river Taff, in the center of the town and in close proximity to the cathedral, about 100 meters away, separated by a dingle. On its north-eastern side, a steep ridge descended towards the river floodplain, which was probably one of the main features of the terrain that influenced the development of Llandaff. An important old trail ran down to the river ferry near the castle, connecting among other with nearby Cardiff.

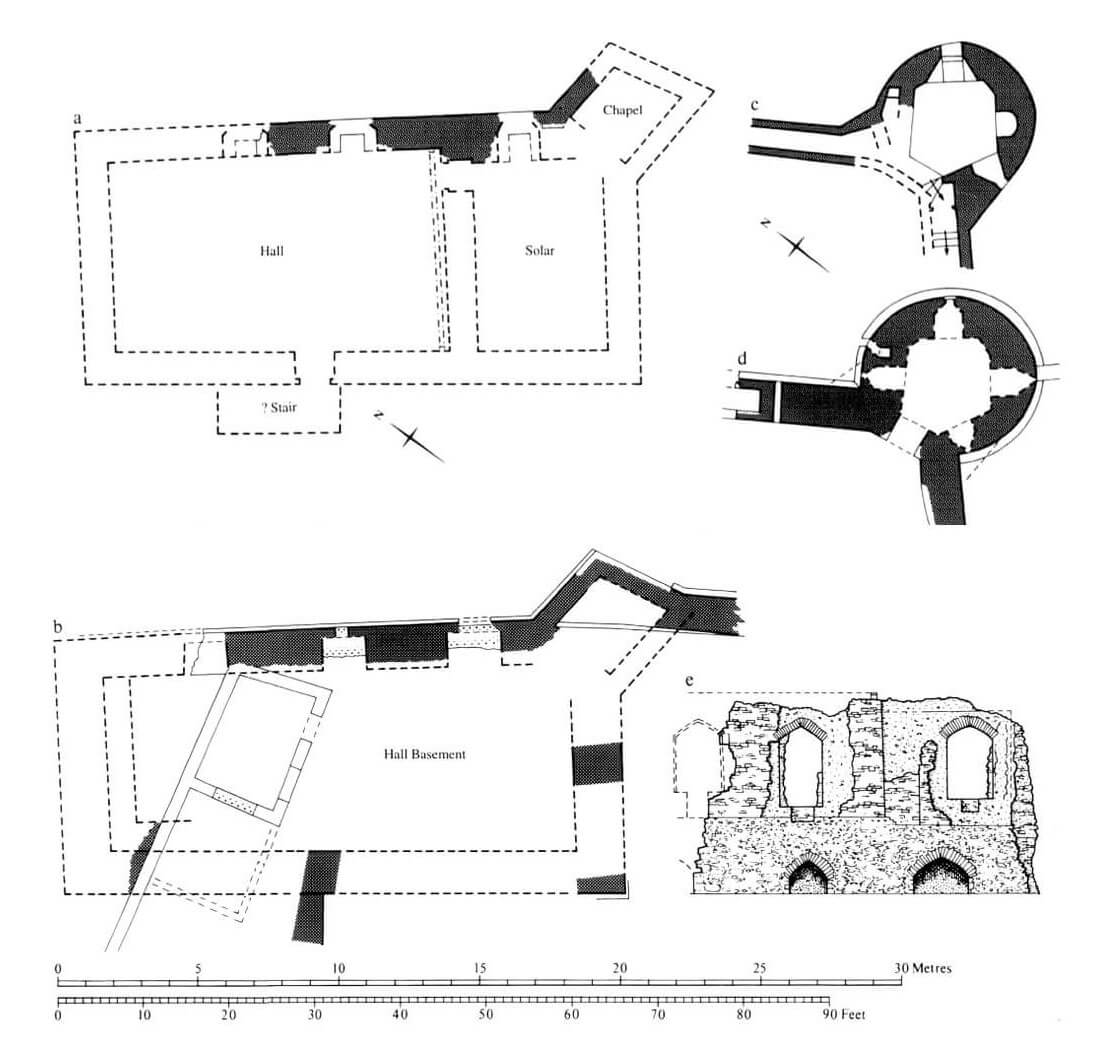

The castle was a medium-sized complex, erected on a plan similar to a quadrilateral, measuring 52 by 38 meters, with a cut-off northern corner. The defense was provided by a single perimeter of the walls, thick from 1.9 meters (on the south-eastern side) to about 2.2 meters (on the northern part), probably preceded by a ditch, with the exception of the north-eastern side, where the area fell steep slopes. The walls were reinforced with two towers. One of them (eastern) was cylindrical, the other was four-sided (southern). On the north-west side, in the corner of the walls, a gate was placed, and the northern corner of the castle was filled with the building of the bishop’s great hall. The internal buildings of the courtyard were wooden or timberframed.

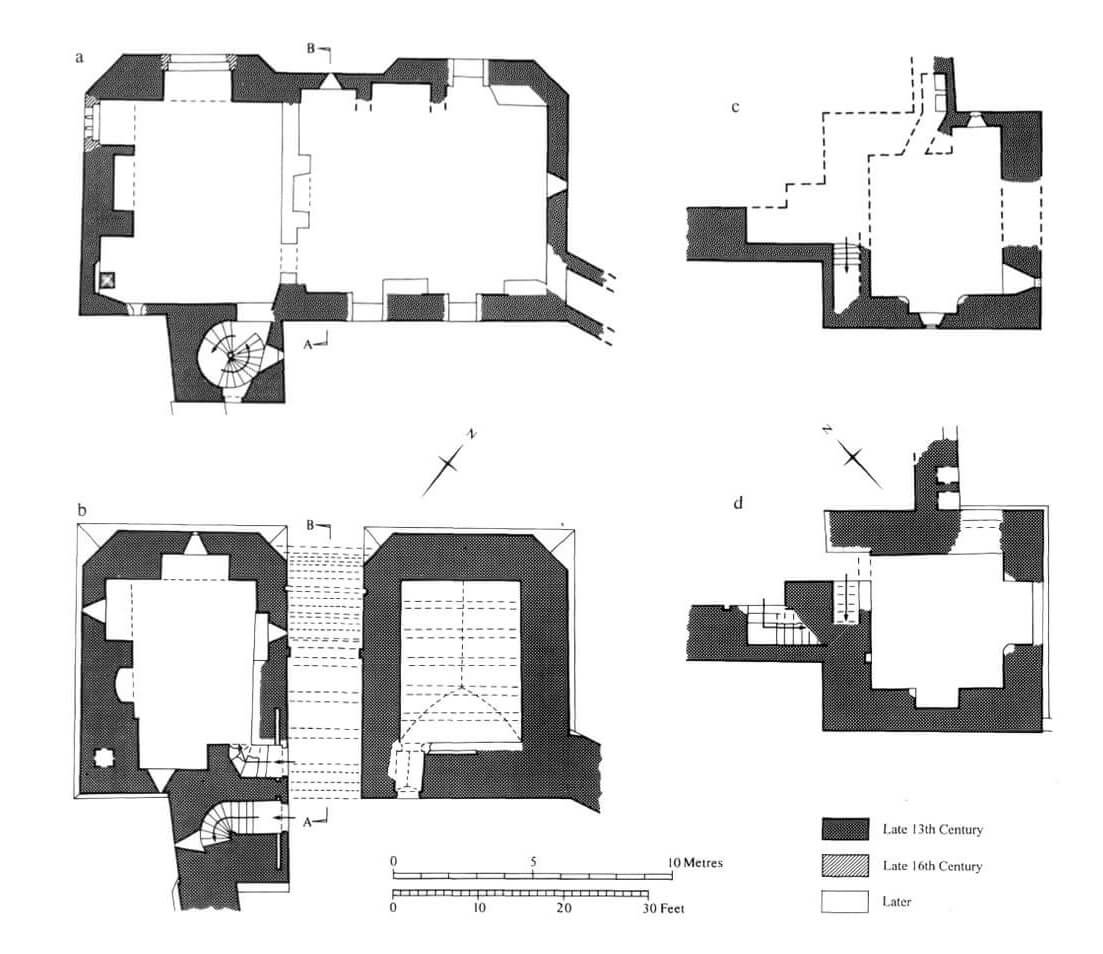

The gate to the castle courtyard was located at a slight slant in relation to the entire complex, which was probably intended to turn the entrance towards the town square and the ceremonial road leading to the cathedral. Connected with two curtains of walls, it consisted of two four-sided towers flanking the passage between them, while the outer corners of both towers were cut and reinforced with small spurs, passing into a plinth widening the structure.

Each of the gate towers had two floors above the basement, located partially below the level of the passage. In the ground floor (about 1 meter above the gate passage), the western tower had four arrowslits, one on each side of the world (one of them was directed to the gate passage). The guards inside the room had a good view of the castle surroundings and a large field of fire, and could also guard the gate passage itself. Unusually, however, the room in the ground floor of the eastern tower was devoid of any arrowslits, only from the side of the courtyard there was an entrance opening, accessible after crossing a few steps. This room also had a stone barrel vault, as opposed to the wooden ceilings of the western tower. As it had a very austere décor, there were traces of a bar on the wall at the entrance, and it had no sunlight, it probably served as a prison cell. Its ventilation was provided only by one small hole set high in the south-eastern wall. The lowest, basement floor of the eastern tower was also vaulted. Originally, it was only accessible of the prison cell, through a hatch in the vault.

The gate passage 2.4 meters wide was covered with a vault and divided into the outer and inner parts by protruding jambs and an arcade in which a double-leaf oak gate, studded with iron fittings, was installed. In each part, the vault was reinforced with three massive, pointed, mostly moulded arch bands. In the outer part, in a special guide, the portcullis was lowered, but no traces of the drawbridge were found. Behind the portcullis, protection was provided by a side, cross-shaped loop hole, pierced from the adjacent guard’s room. In the inner part of the passage on the west side, there was a passage to the guard room and another, located outside the gate passage, leading to the staircase, and to to the top of a slender four-sided turret, protruding above the roofs of the gatehouse. Both entrances could be blocked with a bar set in an opening in the wall.

A slender turret at the back of the gatehouse provided access to its upper floor and to the defensive wall-walk in the south-west curtain of the wall. The large chamber above the gate passage (divided only in the 18th century) had residential functions. It was heated by a fireplace embedded in the western wall and had a latrine placed next to it in a recess. In the eastern wall, it was connected with a wall-walk in the crown of the northern curtain.

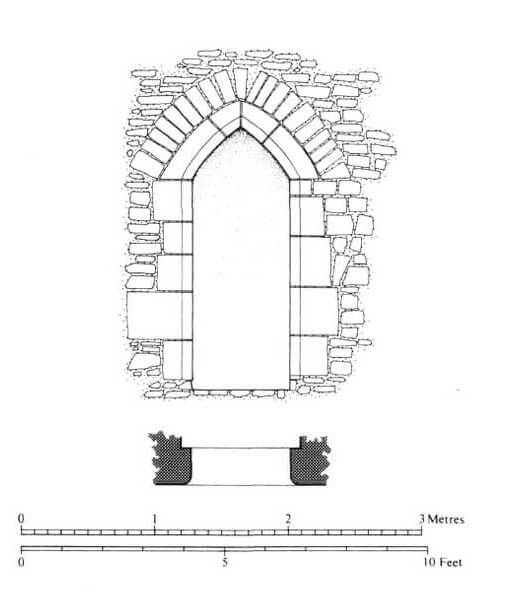

The building of the bishop’s hall was built on a rectangular plan, so its northern corner protruded in front of the defensive perimeter of the castle. Similarly, a small four-sided avant-corps protruded on the eastern side, connected with a simple curtain of the defensive wall. The building received walls 2.2 meters thick, erected just above the slope falling towards the river. Like most buildings of this type in Great Britain, it had two floors: the utility ground floor measuring 6.4 x 16 meters, topped with a stone vault and lit by narrow slits, and the upper residential and representative floor, accessible from the courtyard via wooden, external stairs. Movement between both floors was possible with a staircase in the wall thickness. The upper floor was divided into a representative chamber – the bishop’s hall, measuring 11.9 x 7 meters in the northern part, and a smaller private room (solar) in the southern part. Both rooms were illuminated from the north by similar windows crowned with segmental arches (perhaps with two-light openings filled with trefoils, as in Caerphilly Castle and the Lady Chapel in Landaff Cathedral), embedded in niches with side seats. The southern chamber was additionally connected with an obliquely situated projection, about 3.3 meters long, most likely containing a small oratory or a chapel.

The north-eastern curtain of the defensive wall, like the others, was topped with a defensive wall-walk (at a height of about 5 meters) and battlement on the corbelled parapet. In its part closer to the cylindrical tower, in the thickness of the wall, there was a narrow latrine (or a cistern), covered with corbelled roof, connected to a canal running through the castle courtyard. The latrine also was in the second floor of a nearby cylindrical tower, 5.5 meters in diameter, heated by a fireplace and connected with a wall-walk. Another latrine in the southern curtain of the wall, serving the southern four-sided tower, proved the good sanitary conditions in the castle. This tower, of sides approximately 8 meters, had two floors above the basement partially sunk into the ground. It was accessible from the courtyard level, and straight stairs in the wall thickness led to the top floor. The two upper chambers, as heated by fireplaces, could serve as living quarters.

Current state

To this day have survived the lower part of the twin-tower gate, a fragment of the western curtain of the defensive wall and the ruins of the south-eastern round tower and the south-western four-sided tower. Entrance to the monument is free.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Later Castles, London 2000.