History

The Glamorgan region of South Wales was conquered by Robert Fitzhamon, Baron of Gloucester, at the end of the eleventh century. The conquered lands included, among others, the Llanblethian, which Robert was to grant to Herbert de St Quentin around 1102, although the latter held them under privileged conditions, without normal feudal obligations, which would indicate that he had settled in Llanblethian before the formation of the Norman administration. Herbert most likely was the founder of the first wood and earth fortifications, expanded at the end of the 12th century with a stone keep.

The castle remained with the St Quentin family until 1233. Then it was taken by Richard Siward from the neighboring Talyfan, during the fights related to the anti-royal rebellion of Earl Richard Marshal. The unexpected death of Earl Marshal in 1234 was an opportunity for the king to make peace and pardon the remaining rebels. Siward’s outlawry was rescinded, while Richard Marshal’s brother and successor, Gilbert, soon reconciled with the king and became Earl of Pembroke. Admitted to the royal council, Siward was given custody of Glamorgan, and reconciliation with the rebels inspired the two royal documents ordering the return of Llanblethian Castle to its rightful owners. Despite this, however, John de St Quintin never restored the Llanblethian, in return he had to be content with the goods of Woodhill in Wiltshire, England.

Richard Siward’s tenure did not last long after young Richard de Clare came of age and was able to take over the lordship of Glamorgan. In 1244, Siward broke the truce arranged by the earl with Hywel ap Maredudd, the Welsh Lord of Meisgyn. His provocation was compounded when he allied with Hywel and waged war against the Earl, also involved in the death of Herbert Fitz Mathew near the castle in Afan. He was outlawed and his lands confiscated in favor of Earl Richard. Siward questioned the earl’s version of events and appealed to the king. The case began in curia regis in 1247 but was stopped before sentencing, as Siward died the following year. Llanblethian Castle was not mentioned during it.

The absorption of the Llanblethian into the estates of Richard de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, Lord of Glamorgan, and at the same time the foundation of the nearby town (borough) of Cowbridge in 1254, meant that the importance of Llanblethian Castle could increase. It was at Llanblethian in 1257 that Earl Richard gathered great forces in response to the Welsh attack on Llangynwyd Castle, although in the following years of the 13th century no construction works on the castle were recorded in documents, either under Richard de Clare or under his successor Gilbert II . Moreover, when in 1262 Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, who occupied the castle for twelve months on behalf of the king, detailed the strong garrisons held in the castles of Neath, Llangynwyd, Llantrisant and Cardiff, made no mention of a Llanblethian. It was only Richard’s grandson, Gilbert III de Clare, who began the great reconstruction of the castle when he came of age in 1312. However, these works were interrupted in 1314, due to Gilbert’s death at the Battle of Bannockburn, and the castle was damaged during the Welsh rebellion that broke out two years later.

In 1317, Llanblethian was awarded to Hugh Despenser through his marriage to Eleonor de Clare. Despenser was the infamous royal favorite, hated over time by most of the English nobility, so much that in 1321 a tense situation ended with the outbreak of a rebellion of the Marcher Lords. During it, among other things, the castle in Llanblethian was destroyed, although the Despenser family managed to keep it even after the fall of the royal favorite. This allowed for repair and completion of construction works by Edward Despenser, who died in Llanblethian in 1375. Glamorgan was then under royal custody because of the minority of another Despenser, although it was reported in 1376 that Lord Edward’s widow, Elizabeth, held the castle and court “Llanblafhian” (as well as Talyfan Castle and Cowbridge).

In the 15th century, the first record of the castle appeared only in 1440, when it was in the possession of Isabel, Countess of Warwick. Llanblethian served as the administrative center at the time, the castle gatehouse was used as a local prison, and the castle’s administrators also acted as mayors of Cowbridge. However, already in the peaceful 16th century, like many other medieval strongholds, the castle lost its importance and fell into decline. In the 18th century it was already largely ruined, but the rooms on the ground floor of the gatehouse were transformed into a residential house, which was used until the 19th century.

Architecture

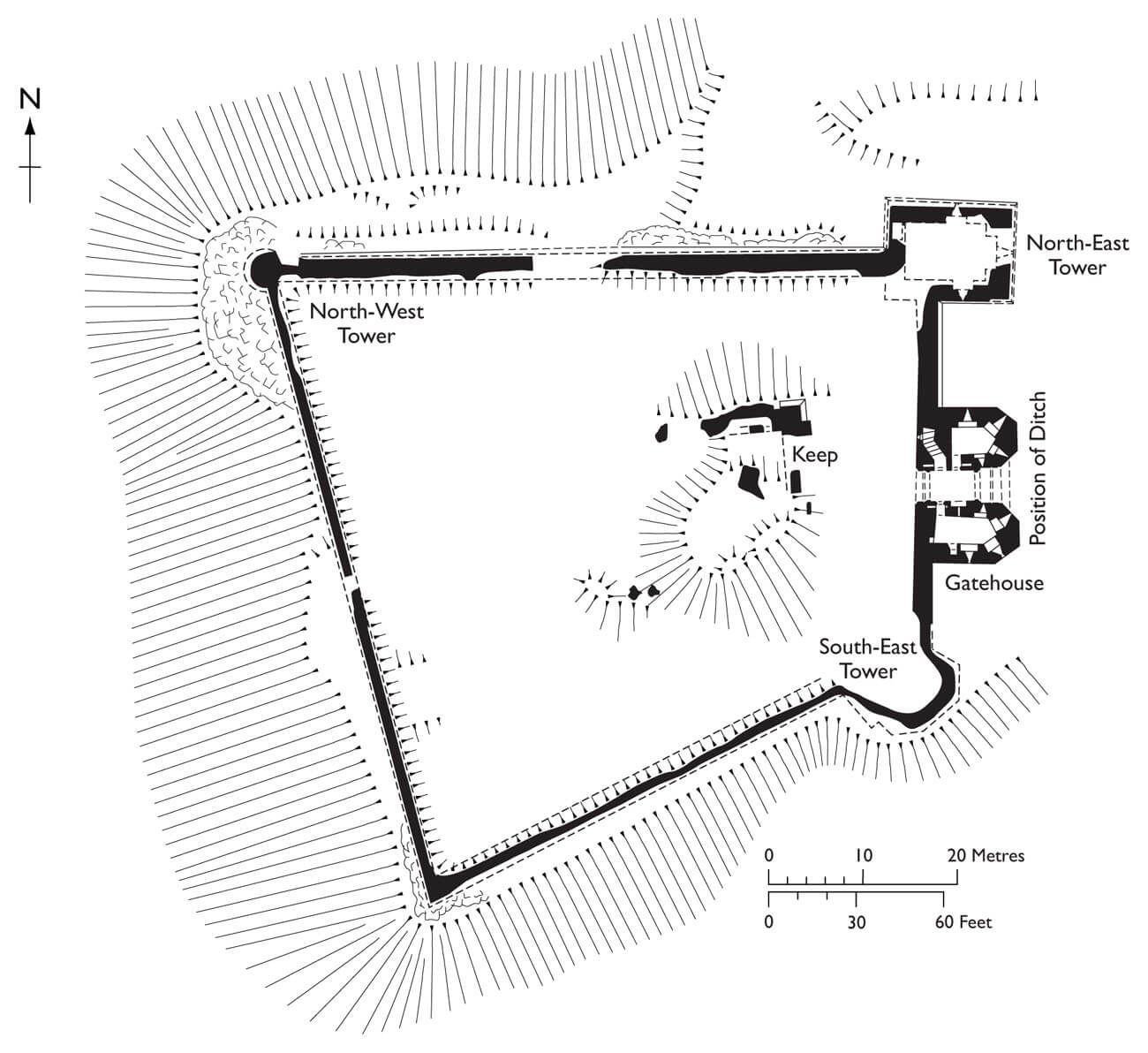

The original castle was in the form of a wood and earth perimeter of the fortifications (ringwork) with a diameter of about 40 meters. It was erected on a low hill overlooking the bend of the Thaw River, which, due to its steep escarpments, provided a strong, natural defense from the north, west and south. Only in the eastern direction the hill faced a flat area without any major natural obstacles. There, the road led to the fortified town of Cowbridge, while the settlement of Llanblethian with church of St. John was located in the valley on the south-west side of the castle.

At the end of the 12th century, a four-sided keep was built of stone rubble bonded with limestone mortar. Probably its sides were about 14 meters long, and the thickness of the massive walls was almost 3 meters. The building probably flanked the entrance gate to the ward, as in the Ogmore and Coity castles. The keep at Llanblethian, however, was larger than any other structures of this type in the region. In the thickness of its northern wall there were straight stairs connecting the ground floor with the first floor. The lowest storey probably had a storage and utility function, while the upper storeys were used for living purposes. It is known that they were equipped with latrines. The connection of the ground floor and the first floor with stairs was a unique solution, because in the vast majority of keeps, this role was played by a hatch in the ceiling and a ladder. Most likely, the reason for this was not the possible vault of the ground floor, as it would have to be at a height of as much as 2.5 meters.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the keep was surrounded by a stone defensive wall about 2 meters thick, delimiting the courtyard on the plan of an irregular quadrilateral, narrowing on the eastern side. The northern and western curtains were about 60 meters long, while the southern one was slightly shorter, about 55 meters. Additional defense of the castle was provided by a rectangular north-east tower with dimensions of 13.5 x 10.5 meters, a massive gatehouse with dimensions of 11 x 16.5 meters in the middle of the eastern section, and a polygonal south-east tower with a diameter of about 10 meters. A much smaller, semicircular turret occupied the north-west corner. Therefore, the eastern section, which was the only one not protected by the natural conditions of the terrain, was strengthened the most. There, and partly on the northern side, where the slopes were not too steep, a ditch was created. The old timber and earth fortifications from the 12th century were leveled, but the keep was raised during this period using ashlar, which, together with its location about 9 meters above the gate, gave the defenders an additional advantage.

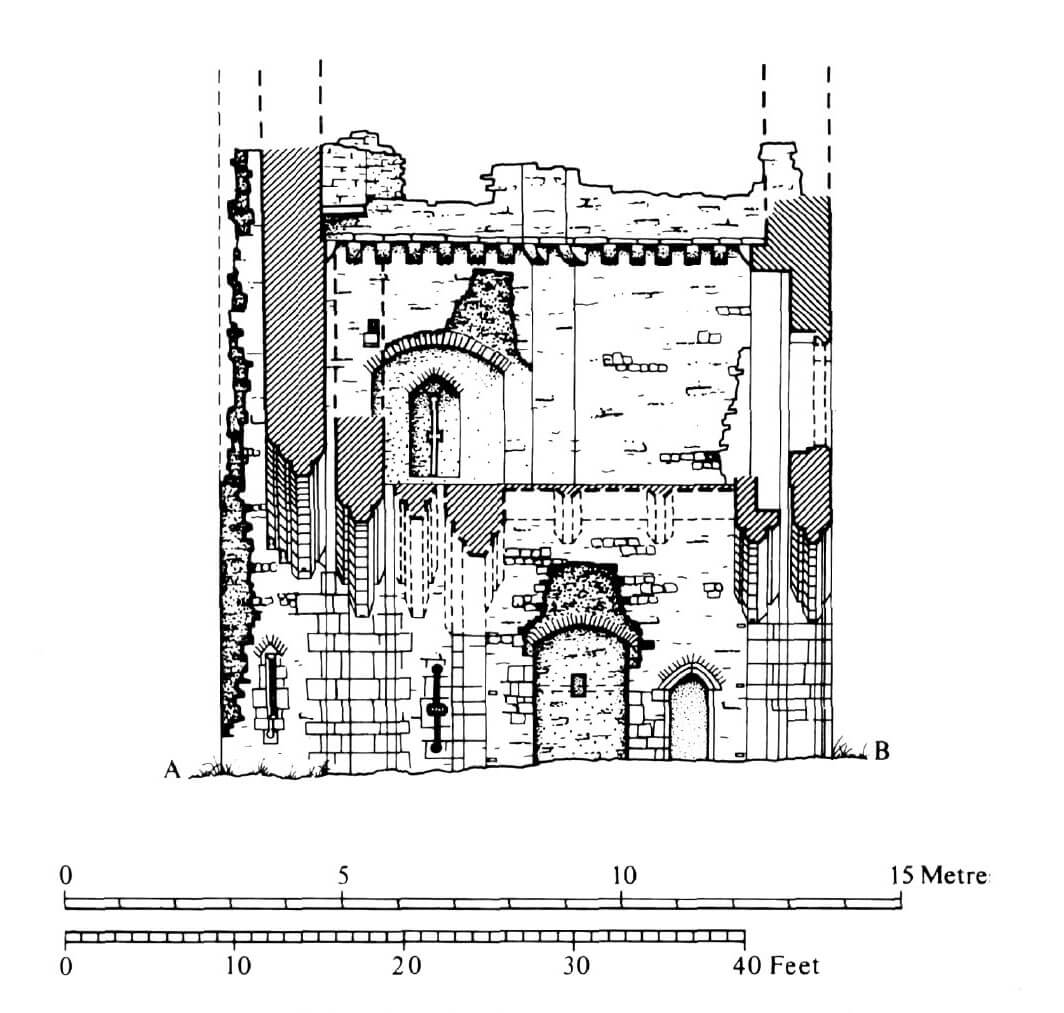

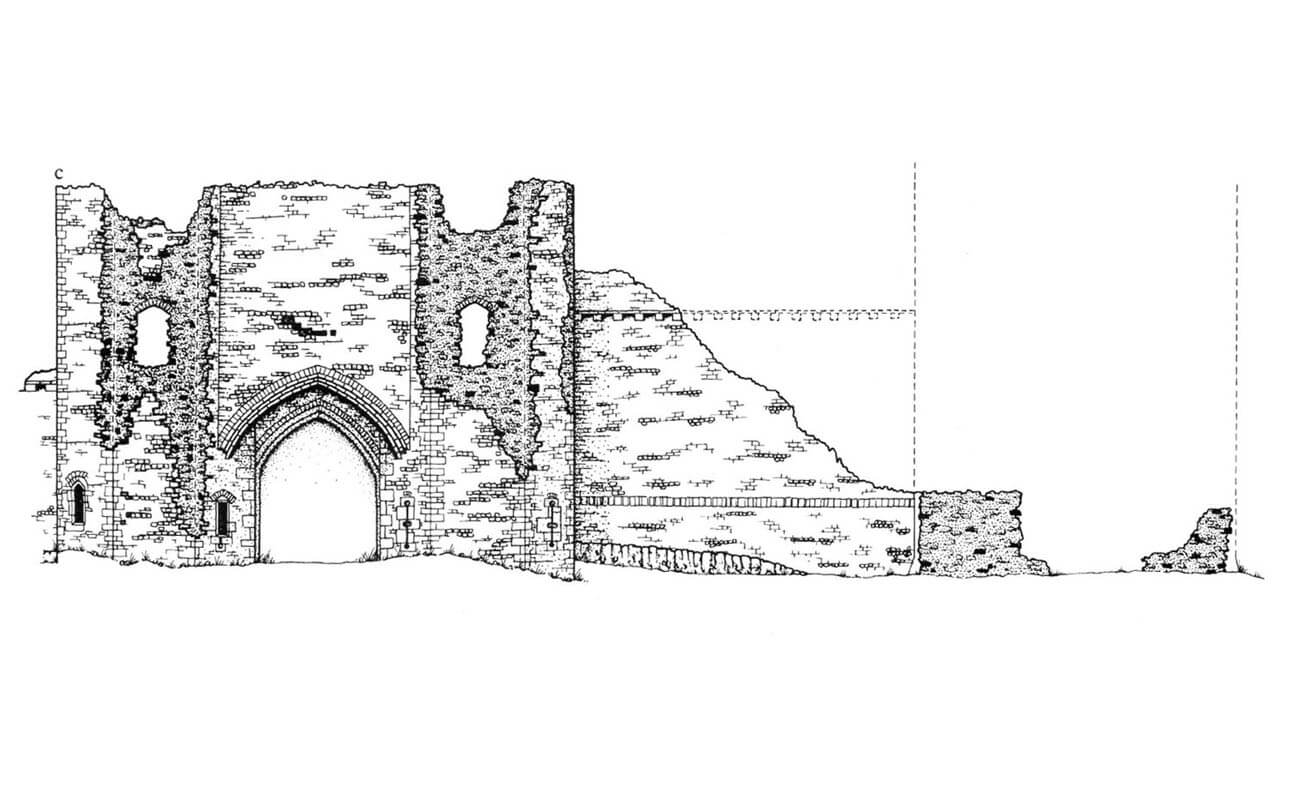

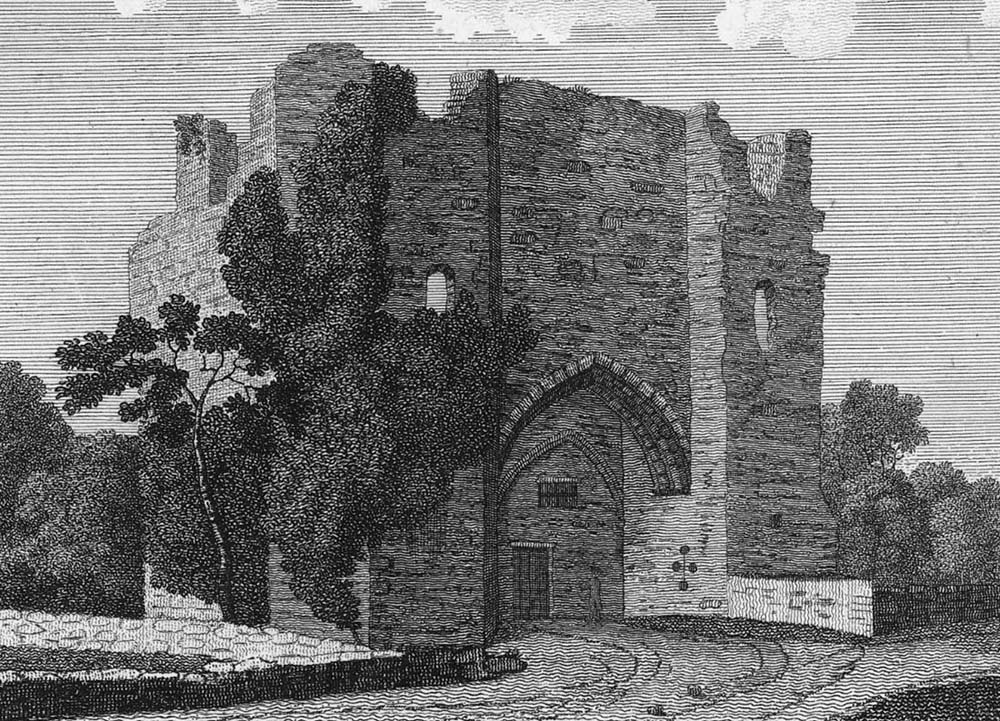

The entrance to the castle was provided from the eastern side by the aforementioned gate complex, built of high-quality material in the form of limestone, carefully prepared and mortared blocks. It consisted of two massive hexagonal towers, protruding entirely in the foreground and flanking the passage between them (the back of the gatehouse formed a straight facade with curtains of the defensive wall, which was a rare solution, possibly due to the close location of the keep). The passage was 10 meters long and 3.2 meters wide. It was closed with two portcullises located at the extremes, and more or less in the middle with a door, and probably also with a drawbridge. It was covered with a vault based on eight moulded ribs, of which the three extreme ones from the foreground of the castle were arcades placed in front of the gate. This sensitive place was additionally protected by the so-called murder holes. On the sides of the passage there were two rooms for guards, each vaulted, with four cross-oillet arrowslits (including three directed to the foreground and one tooward gate passage). The northern room was a bit smaller, because next to the wall there was a staircase to the first floor. It was accessible from the gate passage and, like both rooms, it was closed with a door that could be blocked with a draw-bar set in the opening in the wall. The bar prevented people from getting in from the passage, with the exception of the southern room, closed from the opposite side, which would indicate that it was used in the late Middle Ages as a prison cell. This function probably also served a small hole pierced in the wall of the passage, under the segmental arcade of a shallow recess, which made it easier to watch the prisoners and provide them with meals. The northern room was equipped with four small wall recesses, probably intended for setting the light source.

The first floor storey had only one room, covered with a wooden ceiling, 13.3 x 7.7 meters, so even slightly larger than the main gates of Caerphilly Castle, although the Llanblethian latrine and staircase imposed a reduced overall area and an irregular plan. The room was heated by a fireplace, although it had a military role, not strictly residential, as in many Edwardian castles. The fireplace was small, and the lighting, apart from four arrowslits, was provided by only one narrow, lancet window in the western wall, placed in the recess to which the rear portcullis was raised. There was a latrine in the south-west corner of the room, it was also connected to the adjacent southern curtain of the wall. Little is known about the appearance of the second floor, probably there were living rooms in it, illuminated by larger windows and equipped with a latrine. Unusually, the wall-walk on the northern curtain of the wall was connected to the gatehouse at the height of 10.5 meters of the second floor. This was due to the greater height of that part of the wall, which additionally was a separate defensive work due to two-sided battlements – from the side of the foreground and from the courtyard.

The north-east tower was significantly extended in front of the adjacent curtains: 8 meters in front of the eastern section and 5.5 meters in front of the north. Although it was exposed to fire due to its considerable size, it was protected by the northern, western and southern walls, 2.2 meters thick, and by the most endangered eastern wall, which was up to 3 meters thick (so it had dimensions similar to the keep). A smaller postern could function in the adjacent northern curtain of the wall, facilitating communication with the river and the town of Cowbridge, although it could also be a temporary gate used during construction and later bricked up.

Current state

To this day, the eastern gate complex has survived without the highest storey and with two arrowslits transformed into barred windows, fragments of defensive walls of a small height and fragments of walls in the place of the former keep, of which only a fragment of the northern wall, about 5 meters high, can be seen. The perimeter wall is best preserved on the north (up to a height of about 2 meters) and west side. The north-east tower is visible, however, up to a height of about 2.7 meters. Admission to the castle area is free.

bibliography:

Glamorgan later castles, Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Llandudno 2000.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.