History

The Normans began penetrating southwestern Wales at the end of the 11th century when Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury occupied Pembrokeshire, and Henry de Beaumont, Earl of Warwick conquered the Gower Peninsula. Over the next decades, the Normans sought to expand their territory, which they strengthened by building castles in essential places. Laugharne Castle was one of those strongholds erected at the beginning of the 12th century to secure the crossing of the Taf river. It was recorded for the first time in documents in 1116 under the name of Abercofwy, when a man named Bleddyn ap Cedifor, a native Welshman who took the invaders side and got in exchange the administration of Laugharne.

The castle remained in the hands of the Anglo – Normans throughout the period of anarchy and Welsh – Norman skirmishes, after the death of king Henry in 1135. After accession the throne of Henry II in 1154, the situation improved and after fifteen years the king reached an agreement with Rhys ap Gruffydd, the ruler of the Welsh Deheubarth. Some of the negotiations were conducted in the years 1171-1172 took place at Laugharne Castle. The long-reaching agreement however collapsed already in 1189 with the death of kng Henry II. Rhys invaded English castles in south-west Wales, including capturing and burning Laugharne. Only the strongholds in Carmarthan and Pembroke resisted invasions. As a result of the destruction, the castle was thoroughly rebuilt in the second half of the 12th century. However, already in 1215 it was attacked by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth and again burnt, during the Welsh campaign that swept Normans from the main strongholds at Carmarthen and Cardigan. The destroyed castle remained in the hands of the Welsh until William Marshal, the second Earl of Pembroke in 1223, regained it.

Before 1247, the castle passed into the hands of Guy de Brian IV, whose family had extensive estates in south-west England, but he himself went to Pembrokeshire to seek new opportunities. Laugharne owed him a thorough reconstruction in the mid-13th century. Strengthening the fortifications, however, was not enough, because the Welsh, united under the leadership of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, captured the castle and imprisoned Guy in 1258. He was released the same year after paying the ransom, but Laugharne only recaptured his son, also named Guy (Guy de Brian V), during the Anglo – Welsh war in the 70s of the thirteenth century. Due to the fairly easy fall of the castle in the course of recent fights, at the end of the thirteenth century Guy made another modernization of its fortifications.

In 1307, Laugharne and the family estates were taken over by Guy de Brian VI, one of the few members of the family who did not make any major modifications to the castle. In 1330 he was removed from management by his son Guy VII, probably due to health problems verging on insenity. Guy VII was the last and also the most powerful representative of the family, a trusted servant of King Edward III, an admiral and ambassador sent six times with foreign legations. He died in 1390, but the expansion and defense program of the castle from the 14th century apparently brought results, as Laugharne remained unconquered during the Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr at the beginning of the 15th century. Later, Laugharne became the subject of a long-standing property dispute, which was finally settled in 1488, when dilapidated castle passed into the hands of Henry Percy, earl of Northumberland.

In 1535, the sixth earl of Northumberland sold Laugharne to the king, but twelve years later Queen Maria gave the castle to the seventh earl of Northumberland. In 1575 it became the property of John Perrot, who began rebuilding the castle into a Renaissance residence in the style of Tudor. The modifications from this period were mainly focused on improving living conditions and for this reason, among others, huge rectangular windows were pierced in the gate and towers.

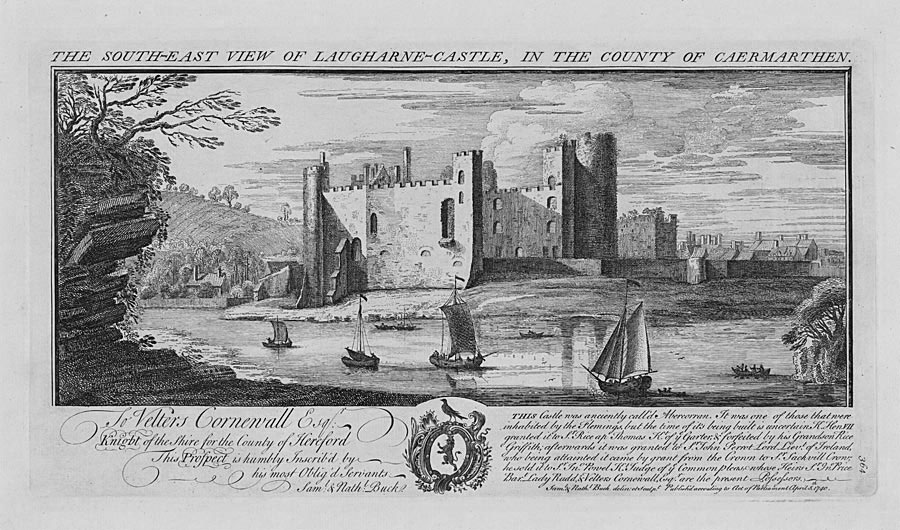

During the English Civil War the castle was first taken over by the forces of Parliament, and then in 1644, captured by royalists. In the same year, Parliamentary troops under the command of General Major Rowland besieged Laugharne, which , after a week’s fire and night attack, was surrendered by the commander of the garrison. Since then, the castle has been in ruin and has never been rebuilt.

Architecture

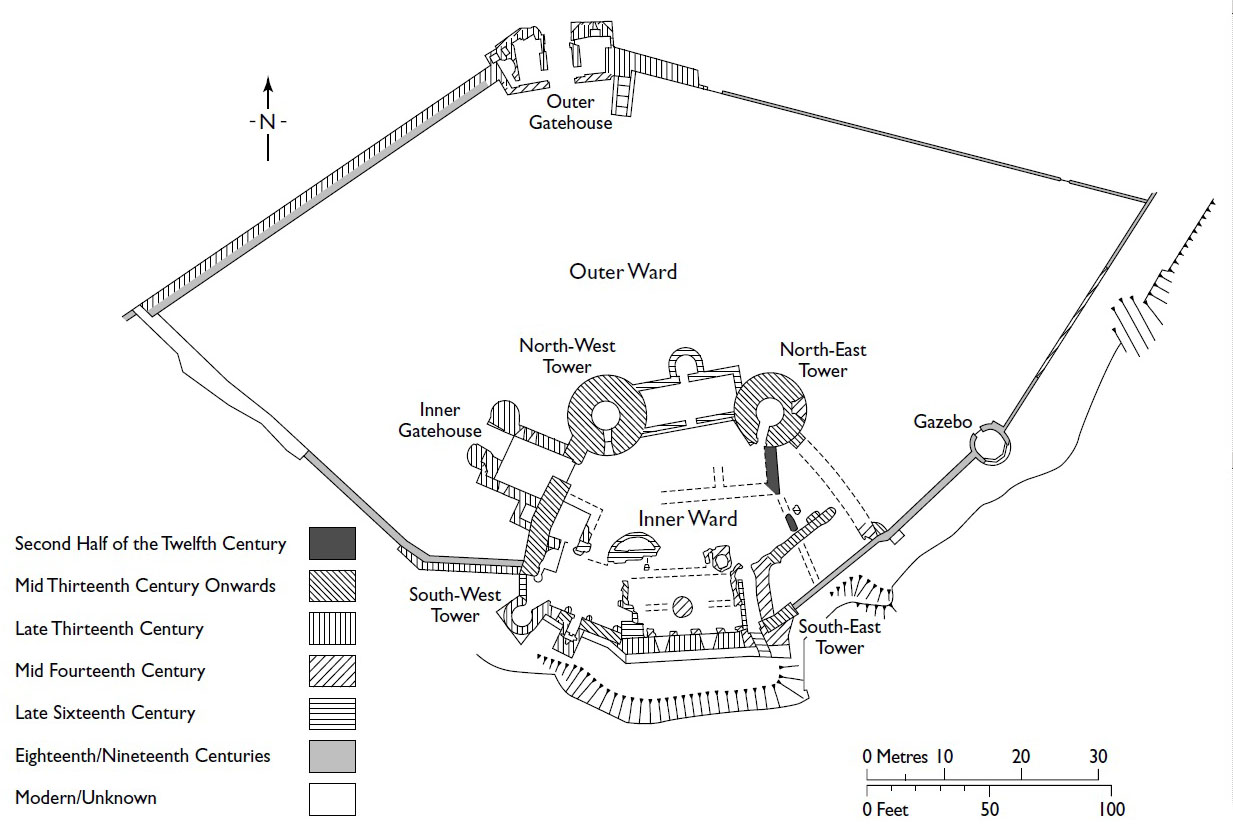

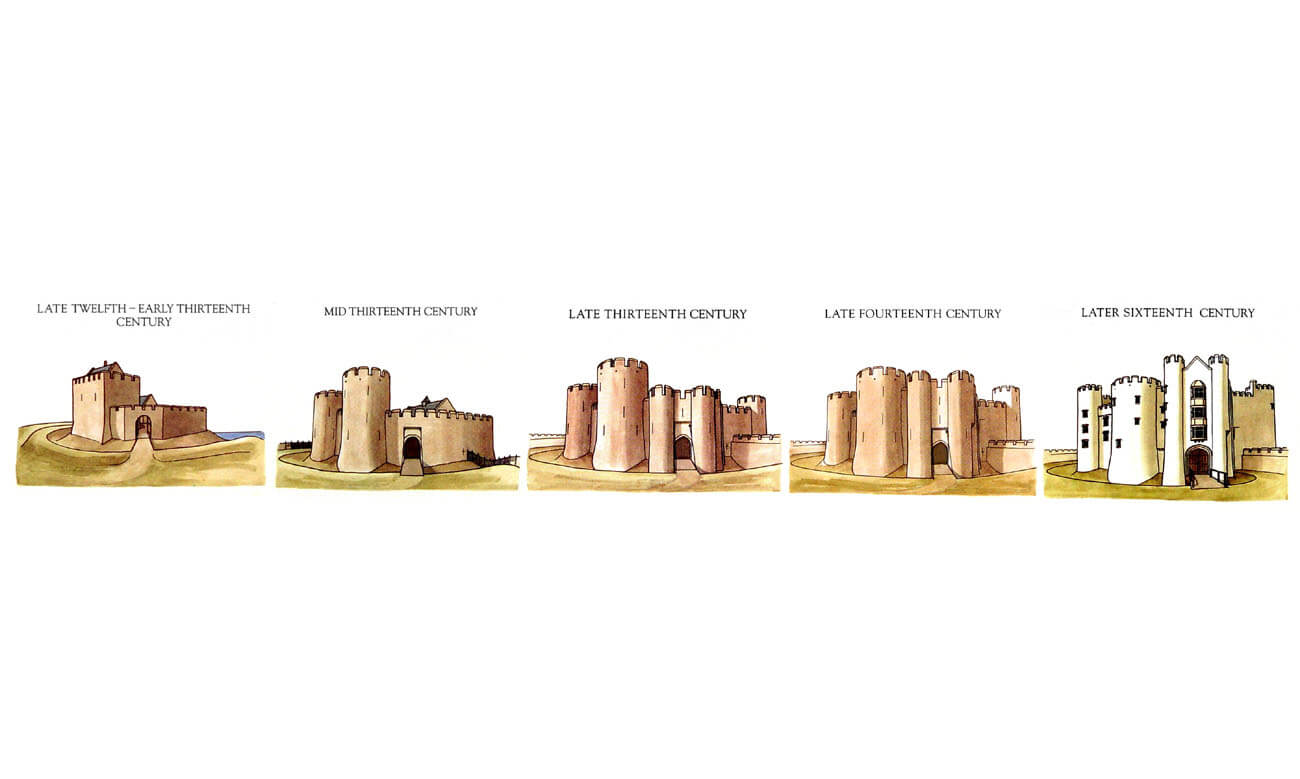

The oldest castle from the 12th century was a relatively simple building, protected from the south by the River Taf, from the west by the Coran stream flowing into Taf, and from the land side by a ditch and an earth ramparts crowned with a timber palisade. Inside, probably the central point was the fortified circuit with a rampart preceded by a ditch (ringwork), in place of the later upper ward.

In the second half of the 12th century, probably in connection with the reconstruction after the destruction of 1189, the defensive wall of the upper castle was rebuilt into stone one, and a large rectangular building 10×16 meters was erected inside the northern part of the main perimeter. It probably had two floors with the great hall in the upper part and utility rooms downstairs (it could be similar to the preserved 12th-century hall from the Manorbier Castle). Additional buildings could be located in the south-eastern part of the courtyard.

In the mid-thirteenth century as a result of a thorough reconstruction, which removed all previous buildings and fortifications, the defense of the upper ward was based on two massive, cylindrical towers (north-west and north-east) included in the perimeter of the walls on the north side. It was a rather unusual system, repeated only at Cilgerran Castle, where the promontory was also protected by two massive round towers. In Laugharne, the ring of fortifications from both towers ran southward toward the low riverside slopes, and then along their edges, closing the area of an irregular polygon, further strengthened in the south-east corner by a cylindrical turret. The entrance was located on the west side, near the north-west tower that flanked it. At that time it was only an ordinary gate portal preceded by a ditch, which stretched in front of the wall from the west riverside to the east. Its width was up to 17 meters.

The larger and more important, also used for residential purposes, was the north-west tower, of a diameter 10 meters and walls thick in the ground floor up to 3.4 meters. It had an unlit basement and three upper floors. In the Middle Ages, access to it was at the height of the first floor, via external wooden stairs located at the courtyard. Inside, vertical communication was provided by a staircase in the wall thickness, except for the basement, accessible only through a hole in the timber ground floor. The ground floor, first and second floor already had stone vaults, with the top floor crowned with a stone dome. Only this room was equipped with a fireplace, but like the lower one, it had no latrines.

The north-east tower was one storey lower, slightly smaller with a diameter of 8.9 meters and with thinner walls, about 2.5 meters thick. It had a basement, accessible from the courtyard, ground floor and first floor, all without vaults. In the ground gloor in the niches there were three arrowslitss, of which the eastern one in the later Middle Ages was transformed into a portal leading to the latrine in the thickness of the wall. On the first floor, on the south-east side, there was a portal leading to the wall-walk in the crown of the defensive wall and a south-west portal lead to stairs in the thickness of the wall leading to the upper defensive gallery.

In the mid-thirteenth century, a new range was erected on the south side, which replaced the destroyed hall from the twelfth century. This new range contained utility rooms on the ground floor and a great hall on the first floor. On the west side it was adjacent to the castle kitchen.

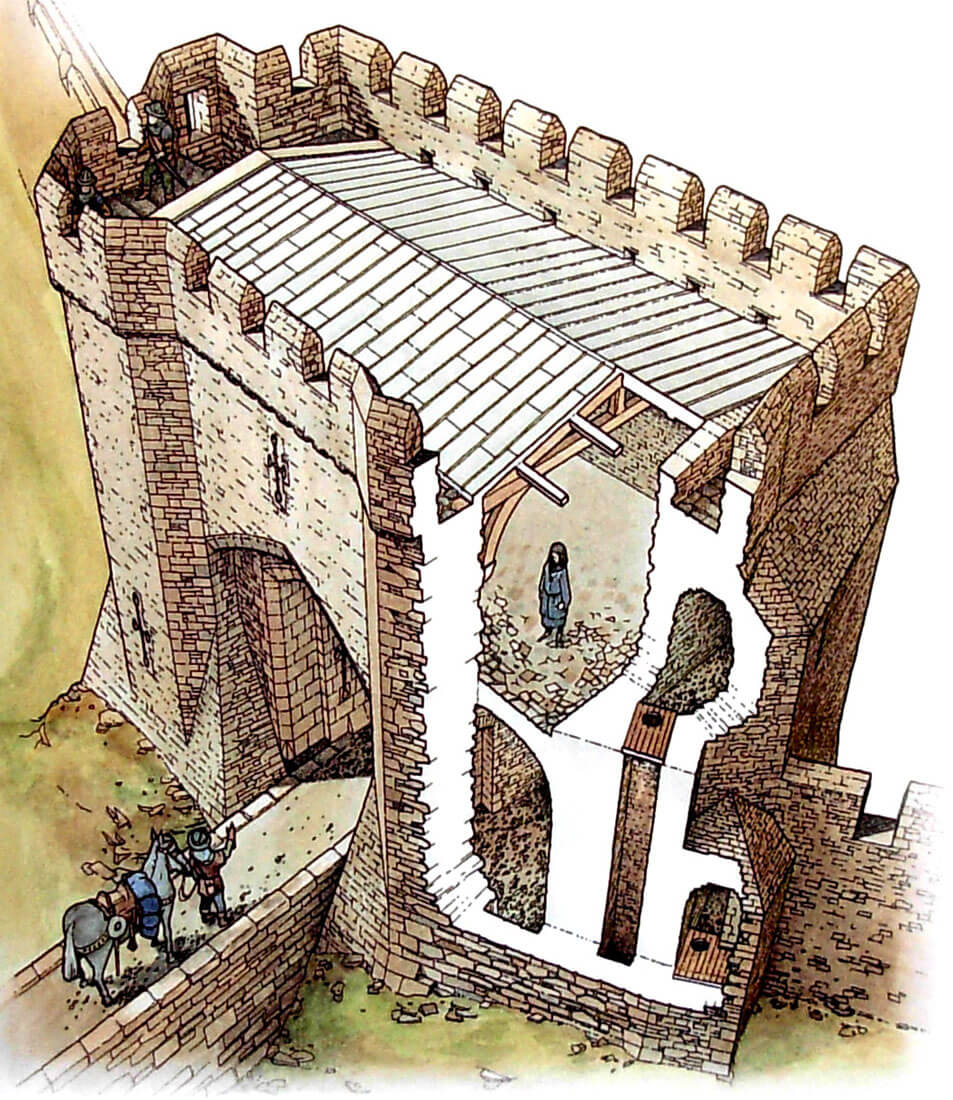

At the end of the thirteenth century, to protect against further fall of the castle, Guy de Brian V strengthened the north-west gate of the upper castle, erecting a quadrangular gatehouse protruded entirely in front of the perimeter of the wall with two semicircular towers from the outside flanking the passage between them. Initially, the gate in the aboveground part consisted only of the ground floor and the first floor, whose external facades were pierced with narrow, arrowslits. Perhaps the gatehouse was also equipped with hoarding, after which there are square holes in the wall. The entrance took place on a timber drawbridge over the ditch, to the gate passage, separated from the right by a partition wall. Behind it corridor led to the upper room of the guards heated by a fireplace. There was also a basement in the gatehuse, as the gate was founded in front of the perimeter wall, on the ditch site. Thanks to this, the builders could apply an unusual solution in the form of a lower postern gate, pierced below the main entrance portal and a drawbridge, which provided access to the new ditch. The basement occupied the entire space below the gatehouse and was topped with a wooden ceiling based on stone corbels. It was buried only in the fourteenth century, when the gatehouse was raised. From the side of the courtyard, the gatehouse was probably closed only by a wooden wall. It was connected to the defensive wall-walk in the crown of the walls and then to the north-west tower.

At the end of the 13th century, a soaring, probably three-story, cylindrical tower with spurs and a smaller latrine next to it were added to the south-west side of the castle. The new tower protected a nearby postern gate opened in the perimeter wall and closed with a portcullis, leading to the riverfront. The curtain of the southern wall was also rebuilt (perhaps because of static trouble), which was considerably thickened. As a result, the internal not very spacious courtyard was overwhelmed by high walls and older buildings of the southern range and kitchen in the south-west corner. The area of the courtyard was cobbled at least from the 16th century.

The northern fortifications of the outer ward (about 80 x 50 meters), which until now were made of wood, were rebuilt into stone ones and reinforced with a double-tower gatehouse on the north side. It had a vaulted gateway on the ground floor, two vaulted rooms for the guards on the sides and a room on the first floor which was accessed from the crown of the defensive wall. Stairs on the first floor of the gatehouse provided access to the upper defensive gallery protected by a parapet with battlement, and in the western tower both floors had access to the latrines through the passage. The outer wall surrounded the irregular courtyard on the north side of the upper castle and connected to its sides from the east and west near the riverside slopes. The outer zone of the outer ward defense was a ditch, while the internal buildings probably consisted of wooden or half-timbered buildings for economic purposes: stables, granaries, forge, brewery, etc.

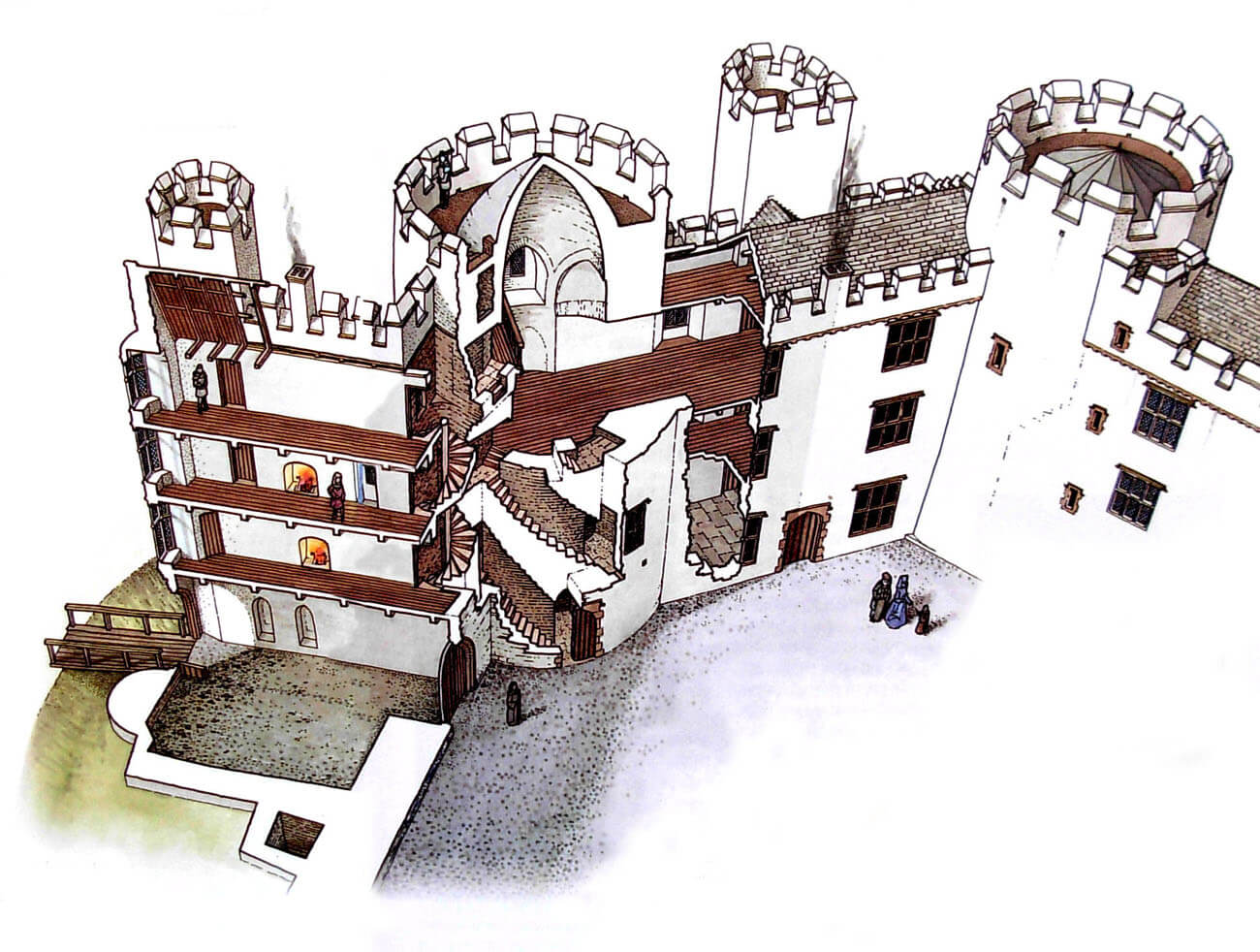

Construction works were continued in the fourteenth century by Guy de Brian VII, who raised the walls, gatehouse with its towers and the south-west tower, added a new tower on the south-east side, and also significantly raised housing standards. The southern hall building was extended to the east, and a lateral postern gate was created in its corner at the end of the passage. In the middle of the hall a massive column was placed, probably serving as the basis for the hearth on the first floor. The second floor of the gatehouse, which was then raised, may have served as a chapel from then on. At the time, it was also equipped with corner latrines which chutes were directed towards the ditch. In the fourteenth century, the kitchen was also transformed and received a large fireplace on the first floor.

The last modifications were brought by the Renaissance rebuilding of the 16th century. In addition to piercing large, rectangular windows in towers and gatehouses, a new wing was erected with a narrow semi-circular tower between the cylindrical northern towers of the upper castle and a new wing at the eastern curtain was built.

Current state

The castle has survived to modern times in the form of a ruin. Almost the entire outer perimeter of the defensive walls is visible together with the north gatehouse ruined during the English Civil War, but a large part of it is the result of 19th-century renovation works. The original medieval outer wall has been preserved only on the north-west side. The 13th-century north-west tower (with a battlement from the 20th century renovation) and partly north-east tower, as well as the slender south-west tower from the end of the 13th century also have survived. From the main gatehouse to the inner ward is visible only, rebuilt in the sixteenth century, the outer, northern facade. Also only the outer wall has survived from the southern range. The castle is open from March 24 to November 4, from 10:00 to 17:00.

bibliography:

Avent R., Laugharne Castle, Cardiff 1995.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.