History

In the first half of the fourteenth century, the palace was expanded again by Bishop Henry de Gower, although due to the spread of Black Death epidemic in 1348-1349 and numerous deaths of tennants, the income from agricultural production dropped. In the following years, Lamphey often hosted bishops and their entourages, probably being their favorite residence. Because of this, the palace became the administrative center for the entire diocese of St Davids. For example, in 1486 an interrogation of Roger Burley, a chaplain from Pembroke, who was accused of heresy, was conducted in the palace chapel. Soon after, probably before 1510, one of the palace buildings (Western Hall) was rebuilt. Perhaps in it, in 1507 bishop Robert Sherborne hosted Rhys ap Thomas, who along with other knights traveled through Wales on the way to the tournament at Carew Castle. Robert’s successor, Bishop Edward Vaughan, also treated Lamphey as his favorite residence. Among others, he rebuilt the chapel and erected a large barn. The survey made at the time of the death of Bishop Richard Rawlins in 1536 described that the palace had as many as 27 chambers, most of which were richly furnished and decorated with hangings and carpets. Seven chambers were to be intended for guests, and further rooms for the servants, which included, among others, a cook, a porter, a barber and a brewer. The bishops also owned an extensive library in Lamphey with valuable collections of humanists, philosophers, medical and legal works.

In 1536, William Barlow became the bishop of St Davids, and moved the cathedral of the diocese to Carmarthen. In 1546, he gave his rich Lamphey, perhaps under pressure, to King Henry VIII in exchange for a valuable rectory in Carew. The palace became the property of the Crown and was given to Richard Devereux in the same year, and then to the earls of Essex. In 1642, just before the outbreak of the civil war, Lamphey was the home of Major John Gunter, who leased the property from Earl Robert Devereux, who became commander in the Parliament’s army. Soon the palace was garrisoned, and local estates had to provide for soldiers maintenance. There are no reports of Lamphey from the war period, but it is possible that palace suffered some damages. In 1683, the Lamphey was sold to the Owen family of Orielton, probably just because of the previously suffered damages. The buildings have since been used only for economic purposes.

Architecture

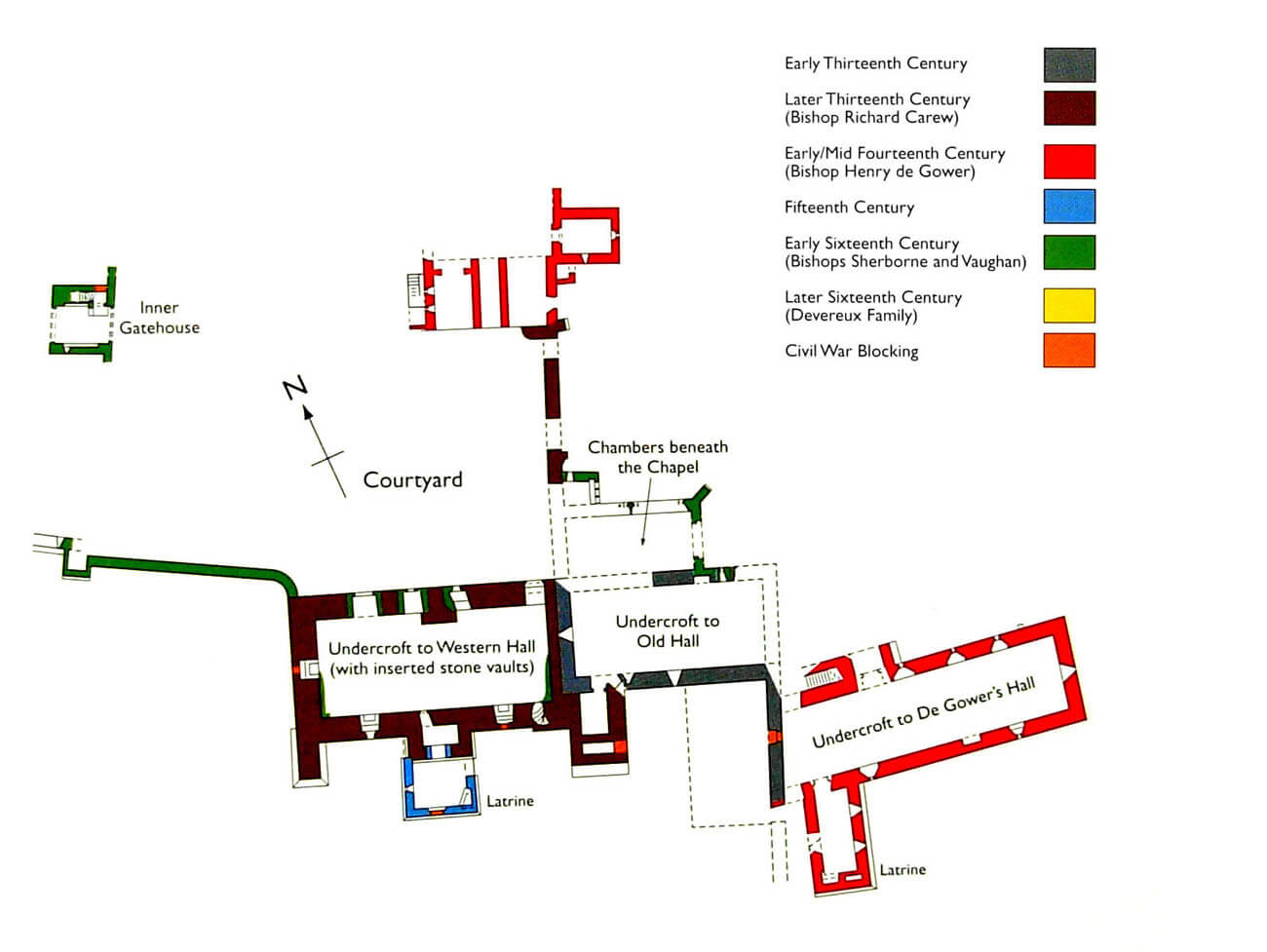

The oldest element of the bishop’s seat was the early 13th-century rectangular Old Hall building with dimensions of 14 x 6.5 meters, erected on a rocky outcrop, perhaps originally surrounded by a ditch. Already at the time of erecting it had a undercroft with a timber ceiling and upper floor topped with an open roof truss. It served upstairs as a place of meals, feasts, meeting guests, while the ground floor served as economic functions. Lighting on the ground floor was provided by narrow slit windows, while the upper floor windows were pointed, slightly larger, but also narrow. Less than fifty years later, the Old Hall was transformed into a kitchen, pantry and service rooms.

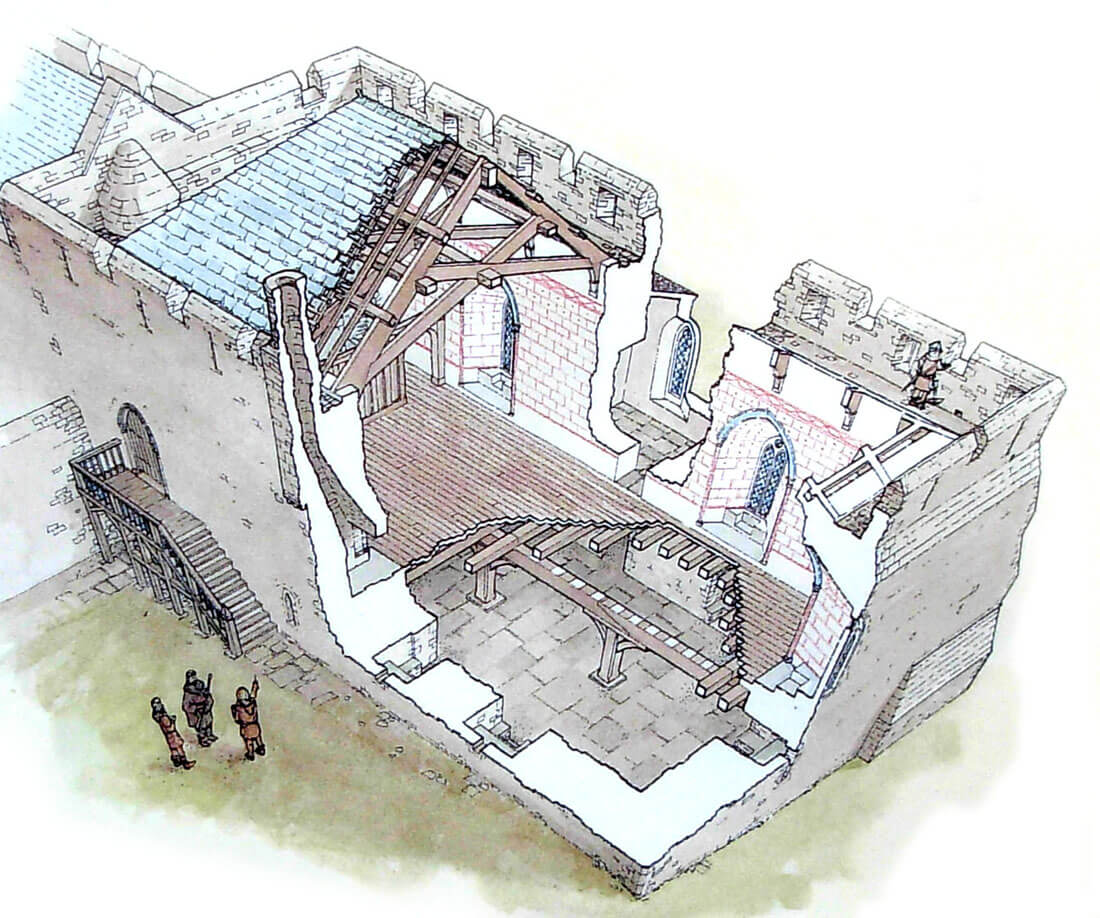

In the second half of the 13th century, next to the Old Hall, Bishop Richard Carew erected a larger (17 x 7.5 meters), but also on a rectangular plan, building of the Western Hall, which replaced the functions of the earlier structure. The Western Hall also had an economic undercroft, separated by a wooden ceiling from the representative upper floor. This ceiling consisted of oak joists embedded in the openings in longer walls and was based on a single massive beam running along the entire length of the building, supported from below by several timber poles. On the south-west side the building structure was reinforced with a massive corner buttress, while in the south-east corner cylindrical stairs were placed in the wall thickness ensuring vertical communication. The entrance was located at the north side, from the courtyard. It led to the interior of the ground floor, and above through wooden stairs to the first floor. There, in the middle of the north wall, a fireplace was placed, and the light passed through four large two-light ogival windows, placed in niches flanked by small stone seats. These niches were framed by arcades flowing down to two shafts, crowned with capitals of stiff-leafs forms. The windows allowed view to the south, towards the fish ponds and the village church, and to the west towards the stream flowing through the valley. In the middle of the southern facade of the hall, a small projection protruded, perhaps intended for the bishop himself (it was located right opposite the fireplace). The interior was decorated with wall paintings put on plaster in the form of red lines dividing cream-white surfaces. Red rosettes were also placed in the middle of some panels. The eastern (entrance) part of the upper floor was separated by a timber screen, protecting the main hall from draughts. The eastern part, because it was adjacent to the economic at the time Old Hall, was equipped with two cabinets placed in the thickness of the wall and connected to the older building with a new portal. The building was topped with a parapet with battlement and had numerous arrowslits pierced in merlons. In the south-eastern corner, in a separate small wing perpendicular to the Old Hall, latrines were placed, while the courtyard north of the buildings was then surrounded by a stone wall.

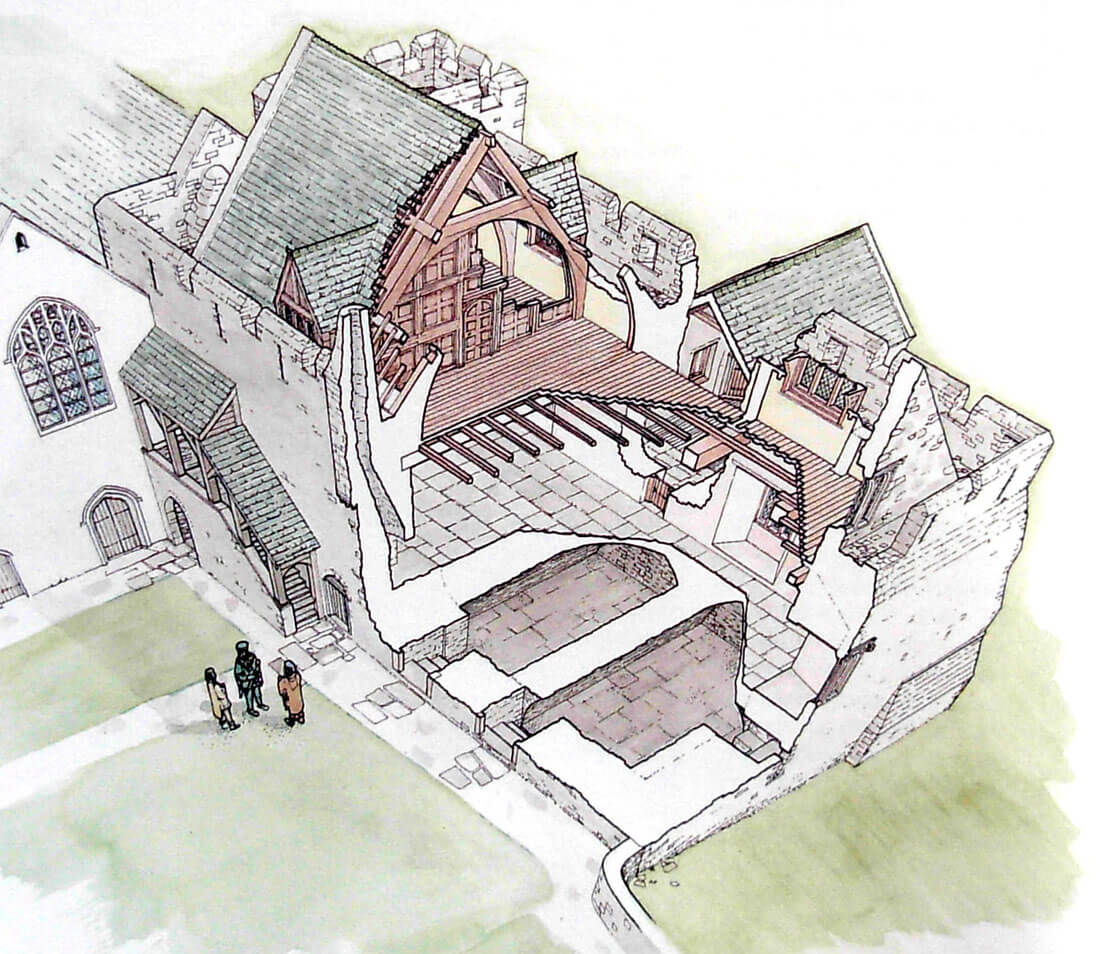

In the first half of the fourteenth century, the great expansion was made by bishop Henry de Gower. He erected south-east of the West Hall, a new rectangular building called the Gower Hall or the Great Hall, situated apart from the remaining rooms. It was the most significant building of the whole complex, which was to impress the guests being visited there. It was not intended for typical residential or service rooms, but was rather used for occasional ceremonies. This building was 25 meters long, vaulted in the undercroft, originally illuminated by five small windows and had the upper floor to which the external stairs from the north led. A characteristic feature of the building was a row of semicircular arcades illuminating the interior from the north and south. Above them there was a parapet mounted on protruding corbels and a battlement covering the gallery to which a south-west spiral staircase led. The protruding parapet was designed to remove rainwater from the roof without washing the walls. The western wall of the building, slightly slanting, was probably used from an older building dating back to the 13th century. On the south-west side there was a smaller wing with latrines. The main chamber on the first floor, with impressive internal dimensions of 21 x 5.5 meters, illuminated by six two-light windows, quite irregularly spaced, occupied the entire space of the building. Each of these windows was placed in a niche flanked with stone seats, but there are no signs that they were glazed, but only closed with wooden shutters. In the middle of the south wall there was a small fireplace, which certainly could not warm such a large space. Therefore, it is assumed that apart from it, originally open hearths in the middle of the hall were still functioning. The timber roof truss was based on stone brackets placed 1.5 meters above the floor. Similarly, the lower floor, probably because of the cold, intended for storing wine, was a single space. This room was illuminated by six narrow windows with trefoil finials at each of the longer walls and one at the eastern wall. Later, a small fireplace was inserted into the southern wall of the undercroft, and on the west side a covered passage to Old Hall. Also on the upper floor were two new fireplaces and a latrine, although probably Gower’s Hall in the 15th or 16th century because of its secluded location ceased to be used.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the ground floor of Western Hall received a stone vault, an additional roof storey was created, the roof was reinforced with stone gables, and a new room with a latrine was created on the south side, where it extended the old bay and replaced the older window. In place of the thirteenth-century ogival windows, new three-part windows with rectangular frames were also inserted. From the outside, they were decorated with angels holding shields, originally painted with episcopal coats of arms. In addition, a number of new entrances leading to the ground floor undercroft were pierced from the courtyard side. Along with the rebuilding of the Western Hall, the Old Hall adjacent to it was raised, equipped with new fireplaces, windows and entrance portals. This was probably due to the transformation of its interiors into residential chambers.

In the 16th century, a four-sided, inner gatehouse was also built, connected to the battlemented walls separating the gardens. On the southern side, this wall was connected to a small four-sided turret standing in the corner. In this way, the economic bailey was separated from the residential and representative part. The form of the gatehouse was more representative than defensive, because its upper floor was surrounded by ogival arcades. Inside the gate passage, the portal led to stairs in the thickness of the wall leading to the room on the first floor and to the top crowned with battlement. At the inner courtyard there was yet apart the episcopal gardens the 14th-century Red Chamber building, providing additional living rooms equipped with a latrine.

The last late medieval changes were the construction of a chapel before 1522, erected from the north at the Old Hall, and the construction of a huge barn, or rather a grain granary in the northern part of the economic bailey. The building of the late medieval chapel in the style of vertical gothic could replace the earlier building in this place. The chapel itself was located on the first floor, while from the north a small extension could fit the sacristy. Below the chapel were two small chambers, originally lit by a series of mullioned windows.

North of the chapel, the defensive wall separated a vast external courtyard where mainly economic buildings were located. Its largest element was the aforementioned large grain barn, 40 meters long, attached to the defensive wall on the north side of the courtyard. In addition, there was a bakery, dovecot, oxhouse and brewery, mentioned in the survey from 1326. The main, outer entrance gate was in the tower on the north-west side.

Current state

The defensive, medieval palace of the bishops survived to modern times in the form of a ruin. The outer walls of the buildings of the Great Hall and the Western Hall, including latrine annexes, as well as the building of the Red Chamber and the gatehouse tower of the inner ward have survived. Gatehouse today stands alone, as the wall adjacent to it has not preserved. What is visible, however, is the outer defensive wall, almost all around the perimeter, although its western curtain with battlement was created in the nineteenth century. The monument is open to visitors free of charge from April 1 to October 31, daily from 10:00 to 16:00.

bibliography:

Hull L., Castles and Bishops Palaces of Pembrokeshire, Eardisley 2005.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, VII County of Pembroke, London 1925.

Turner R., Lamphey Bishop’s Palace, Llawhaden Castle, Cardiff 2000.