History

Beginning of the church of St. Mary in Kidwelly date back to the early 12th century, when Bishop Roger of Salisbury founded a Benedictine priory in the settlement. The church then served both the lay community of Kidwelly and the monks. They formed a very small monastic community, probably consisting of just the prior and two monks, originally brought from the English Sherborne Abbey and living in the nearby monastic buildings.

In 1223, the church burnt down, perhaps as a result of the invasion of the Welsh prince Gruffudd ap Llywelyn. The reason for this could have been the close links of the Benedictines from Kidwelly with the Anglo-Normans and its subordination to the Sherborne Abbey. In the following years the church was rebuilt and enlarged at the end of the 13th and at the beginning of the 14th century. In 1284, Archbishop Pecham of Canterbury stayed there, controlling all Welsh monasteries. The list of charges against Ralph de Bemester, prior of Kidwelly, was so large that he was even dismissed and sent to Sherborne, though he reportedly returned a month later.

In the fourteenth century, only the prior lived at the church, and the income was low, despite the fact that in 1291 the monastery’s tithes were valued at the considerable sum of 13 pounds, 6 shillings and 8 pence. In 1403, during Glyndŵr’s anti-English uprising, rebel troops besieged the nearby castle. It managed to defend, but the town and priory were devastated. In 1481 church suffered further damages as a result of a lightning strike in the tower. The high spire often attracted lightnings, as the strikes were recorded again in 1681, 1854 and 1884.

In 1539 the Benedictine priory at St. Mary’s Church was dissolved, like most others in Wales and England, removed as a result of Henry VIII’s reformation. The church, along with its patronage, became the property of the Crown and from then on it only served as a parish for the local population. In the early 17th century the roof covering of the church was to be replaced, thanks to which the building remained in good condition until the beginning of the next century. Several minor repairs carried out in the 18th century also allowed the building to remain in good state. It was not until the first half of the 19th century that the church began to be described as dilapidated. Victorian renovations were carried out in the 1850s and 1880s.

Architecture

The church was situated on the left, south bank of the Gwendraeth Fach river, so on the opposite side of the castle and the fortified part of the town. It is not certain where the Benedictine buildings were located, but it seems that they were not situated in the usual place on the north side of the church due to the lack of space in front of the riverbed. From the west there was a road leading to the town and the castle, so the best place would be the south or east, or possibly north-east, where the bend of the river freed more space.

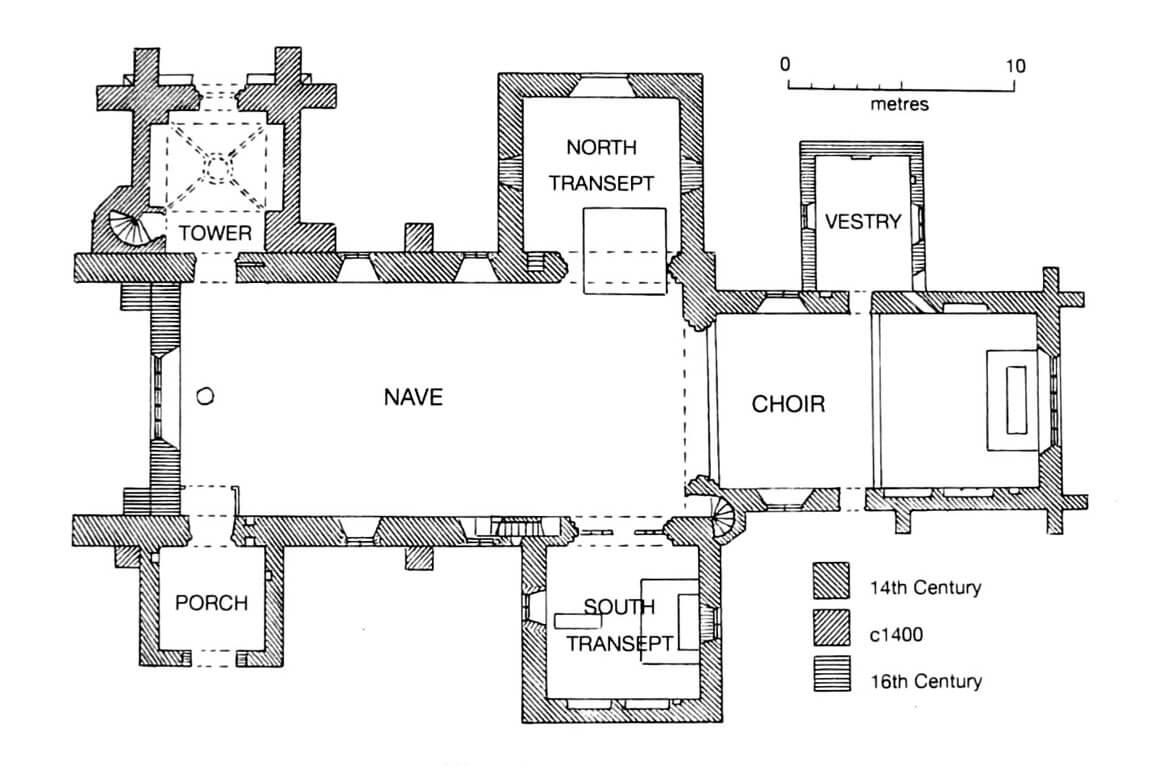

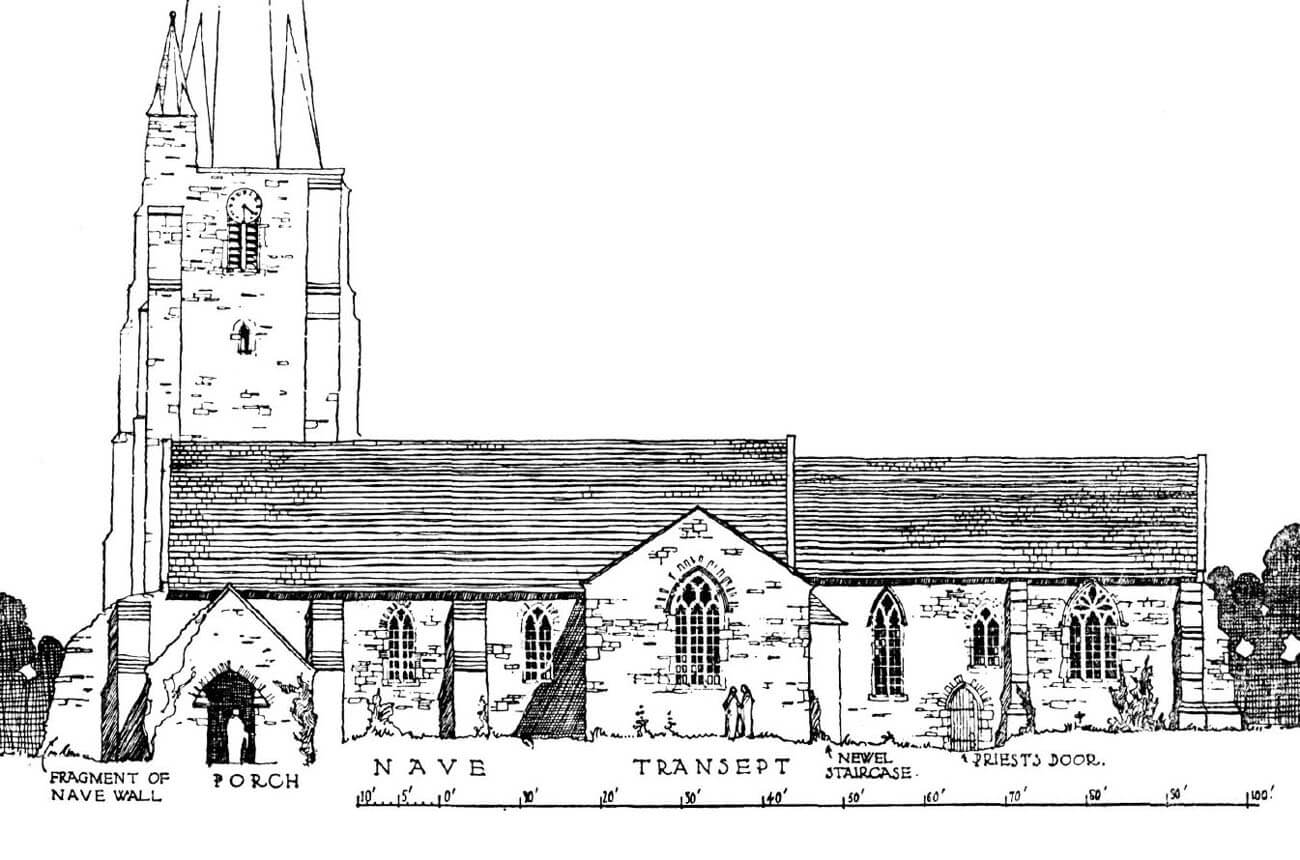

The church at the end of the Middle Ages had a rectangular, four-bay nave, 10 meters wide, and a fairly long, two-bay, rectangular chancel, with a total length of about 37 meters inside. The nave was originally longer, but was shortened by two bays at the end of the 15th or in the 16th century. On its northern side, around 1320, a soaring, three-story tower was built, with a base measuring 7.6 x 7.6 meters, reinforced with corner buttresses and topped with a high spire, originally surrounded by decorative battlement. On the south-west side, the tower received a two-level annex housing a staircase. In the 14th century, the southern and norther transepts were also built, a porch in front of the southern entrance to the nave, and a chapel attached to the northern wall of the chancel.

The long walls of the nave were initially smooth, separated only by window and entrance openings. Secondarily, perhaps towards the end of the 15th century, it were supported by buttresses, with two massive western buttresses created from shortened longitudinal walls of the nave, and more added after some time from the north and south. The chancel was supported by slender, stepped buttresses since the 13th or 14th century. In the eastern corners, they were set parallel and transversely to the axis of the church. Despite the buttresses, the nave and the chancel did not have stone vaults. It were covered with a wooden barrels or open roof truss. The buttresses must have had great structural significance for the slender and tall tower, which thus acquired a form very unusual for the region. Its ground floor was covered with a cross-rib vault, with a large central opening for ropes connecting to the bells.

Inside the church, the nave and the chancel were connected by a wide arcade with a very low archivolt, which gave its pointed arch an almost segmental form. The arcade was moulded with shallow rolls and concavities, without imposts or capitals. The arcades connecting the nave and the transept, created at the same time, had a similar form, but a smaller span. In the Middle Ages, the nave was separated from the chancel by a rood screen, which was a buffer between the western part accessible to laypeople and the eastern part intended for priests and monks. The rood screen was equipped with an upper loft, accessed by a spiral staircase, set in the thickness of the wall at the junction of the southern transept and the chancel, protruding with a slight projection outwards. The rood screen may also have been placed in front of the northern transept, as stairs to the first floor were created in the thickness of its wall.

In the chancel, the elevations were divided by a moulded cornice into a windows section and a ground floor. In the lower zone, a Gothic piscina and triple sedilia were placed in the southern wall. The piscina was topped with a moulded ogee arch, set on corbels in the form of carved human heads. The archivolt was filled with tracery, and below it was placed an octagonal stone bowl. The sedilia were topped with a gable above each seat and separated by moulded octagonal pillars, which illusionarily pierced the stone bench and were finished with wall plinths on the floor. On the opposite side, the chapel was connected by a portal to the choir, and by a diagonal passage in the thickness of the wall to the presbytery.

Current state

Church of St. Mary is one of the most valuable architectural monuments in the Carmarthen region. Its current appearance is the result of a multi-stage expansion carried out from the 13th to the 16th century, with minor changes introduced in the early modern period. The latter include the removal of the tower parapet with decorative battlements, the renovation or replacement of some tracery and window jambs (north and south windows of the nave, south transept window, west window in the south wall of the chancel, tracery of the east window in the chancel), and the replacement of the roof truss. The interior includes a Gothic chancel arcade, transept arcades, a vault in the ground floor of the tower, a staircase to the former rood screen, sedilia and a piscina in the chancel. A valuable element is the tower spire from the beginning of the 15th century, renovated in the 18th and 19th centuries.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Ludlow N., Carmarthenshire Churches, Church Reports, Llandeilo 2000.

Ludlow N., Carmarthenshire Churches, An Overview of the Churches in Carmarthenshire, Llandeilo 2000.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

Salter M., The old parish churches of South-West Wales, Malvern 2003.

Scott G.G., Kidwelly Church, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 2/1856.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, V County of Carmarthen, London 1917.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.