History

The first timber motte and bailey castle was created shortly after the Norman conquest in the 11th century, on a rocky slope overlooking the main medieval route from Chester to North Wales. It was built by Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester and entrusted to the Montalt family, serving as his stewards.

In the thirteenth century, in the time of the weak reign of the English king Henry III and the Second Barons’ War, the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd supported Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort, in exchange for Havarden’s resignation. However, the defeat and death of Earl at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, meant that the castle was never handed over, prompting Gruffudd to attack and destroy the stronghold. Two years later, Gruffudd concluded a new agreement, this time with Henry III, under which Hawarden was to be returned to the rightful owners of the Montalt family, with the proviso that the fortifications could not be rebuilt for another 30 years.

The successor of Henry III, king Edward I in 1277, in a quick campaign, defeated Welsh forces and occupied all lands east of Conwy, including Hawarden. In 1281, work began on the rebuilding of the castle, which, due to the minority of Roger de Montalt, was placed under the protection of the powerful Lord, Roger de Clifford. This was a violation of the Montgomery Treaty of 1267, which forbade the reconstruction of Hawarden. In 1282, Llywelyn’s brother, Dafydd ap Gruffudd, besieged the castle and captured Roger, which led to the outbreak of Second War of Welsh Independence. Edward I quickly invaded the opponents, this time defeating the whole principality. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was killed during the Battle of Orewin Bridge, and his brother Dafydd was captured and eventually condemned to quartering by the English.

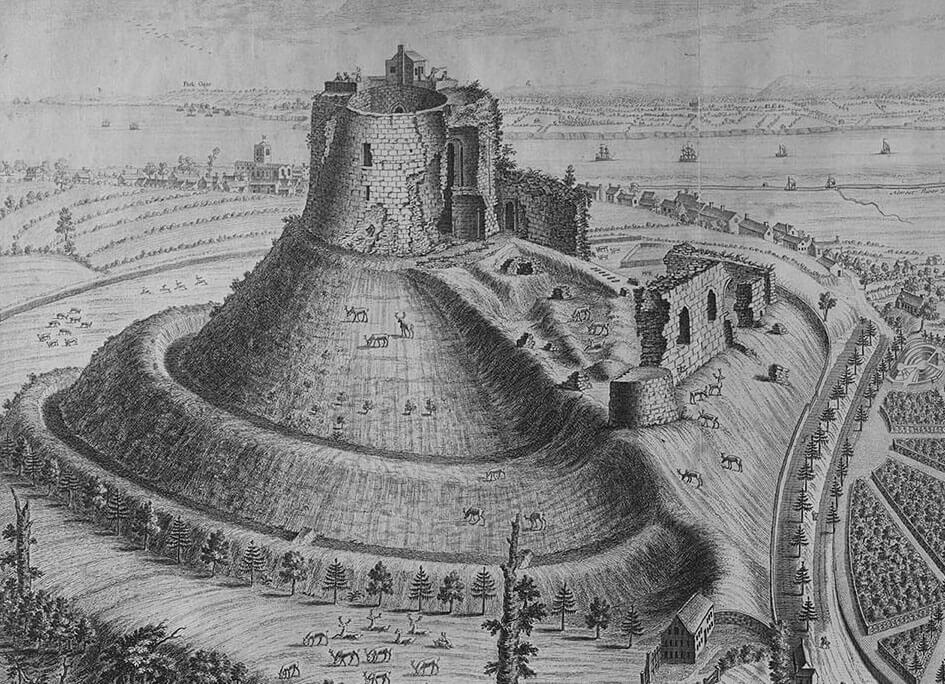

The English victory meant continuing work on the already-stone castle in Hawarden, which, however, lost its strategic importance due to the conquest of the entire North Wales. It was threatened for the last time in 1294, when the Welsh uprising of Madog ap Llywelyn broke out, and at the beginning of the 15th century with the outbreak of the Owain Glyndŵr rebellion. In the following years, the castle passed to the earls of Salisbury of the Montague family, during which construction works were carried out in the second half of the 15th century in Hawarden, and then in 1485 it was donated by Henry VIII to the Stanley family, one of his main supporters. They hosted the king at the castle twice, in 1490 and 1500, probably because of the neighboring deer hunting park.

During the English Civil War, Hawarden was garrisoned by royalists and was one of the key posts surrounding Chester. The city was strategically important because it controlled access to North Wales, including the royal port of Conwy, which hoped to bring in soldiers from Ireland. Consequently, control over Cheshire was a priority for Parliament. In 1643, its forces under the command of Sir William Brereton and Sir Thomas Middleton attacked Hawarden and captured the castle. In response, the royalists, reinforced by 3,000 Irish soldiers, besieged a 120-strong garrison. Thomas Middleton initially refused to surrender, but in the face of additional royalist supports, the garrison capitulated at the end of 1643. The castle was safe for the next two years, until the great defeat of the royal army at Naseby. Hawarden was besieged in May 1645. There was no direct attack, but with the destruction of the last royalist field army at the Battle of Rowton Heath, Hawarden surrendered on the instructions of king Charles I. After the surrender, the castle on Parliament’s order was slighted, to prevent its further military use.

Architecture

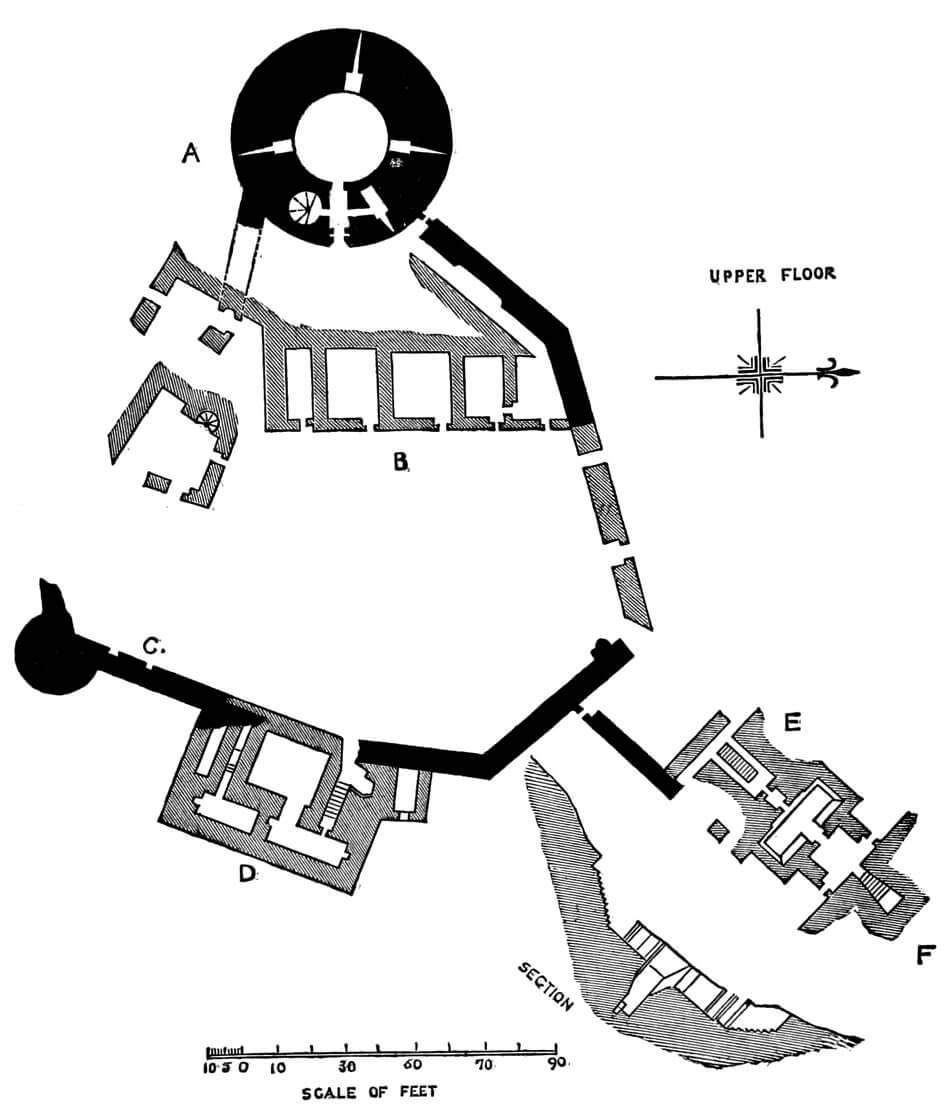

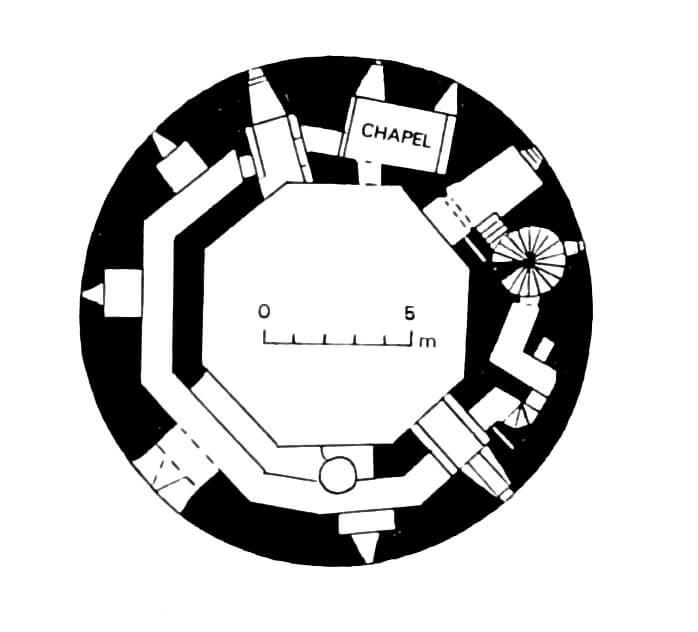

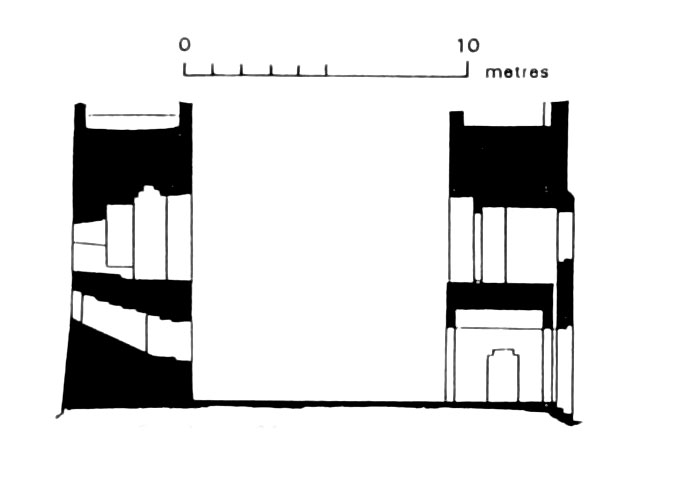

The main element of the castle from the 13th century was a stone, cylindrical keep with a diameter of 16.8 meters, erected on an earth mound. Its massive walls were about 4 meters thick. There was an entrance on the ground floor, protected by a portcullis lowered in stone guides. Inside, the entrance passage was flanked by a four-sided guard’s room embedded in the thickness of the wall, and on the other hand with a spiral staircase, located also in the wall thickness. Straight ahead, a passage led into a central circular room with three arrowslits. Above there was a round room surrounded by a gallery led in the thickness of the wall, leading from the staircase on the south-east side to the chapel in the north-east part (which resembled a solution from the keep of the nearby Flint castle). The chapel was located just above the entrance passage, in the thickness of the perimeter wall. Above, there was probably one more floor.

The chapel, measuring only 4.3 x 2.1 meters, was located just above the entrance passage, in the thickness of the perimeter wall. A portal topped with cinquefoil, only 0.6 meters wide and 2.1 meters high, led to it. The door placed in it opened inwards and could be closed with a bar. On the same side, but closer to the altar, there was a small recess of piscina, topped with a cinquefoil, and on the opposite side, two recesses of splayed openings: one lancet, the other rectangular. A stone bench was placed at the western wall, above which a hole was pierced to allow viewing of the ceremonies from the adjacent window recess with side seats.

At the foot of the mound, on its eastern side, a polygonal defensive wall with a thickness of about 2 meters formed a castle courtyard. Its additional protection was provided by a semi-circular tower located on the south-eastern side with a diameter of 6 meters, protruding in front of the curtain face and having a full (without rooms) base. The adjacent wall curtain was pierced with at least three high windows with cusped openings, set in pointed recesses with side, stone seats. These windows illuminated the building of the representative hall (great hall). Like most of this type, it had two floors: the main, upper room and the lower utility and storage room separated by a wooden ceiling placed on stone corbels. Probably in its vicinity there was a kitchen building and smaller outbuildings.

The entrance to the castle was from the north-east. At the end of the Middle Ages, it led through a long gateway, which was a two-storey building extended far in the foreground, with a drawbridge over the pit created in the ditch and a side sally port. It led to nearby D-shaped earth fortifications, to allow access to the adjacent pond, as the castle had no internal water source other than rainwater.

In the later period of the Middle Ages, a massive four-sided residential tower was erected in front of the eastern curtain of the wall. It housed a central room in the ground floor and inside very thick walls, two additional chambers and a simple flight of stairs to the upper floors. In addition, the projection on the north side housed latrines serving the tower chambers. In the fifteenth or sixteenth century, a building was also erected in the western part of the courtyard, at the foot of the mound with a keep, and a building in the southern part of the complex.

Current state

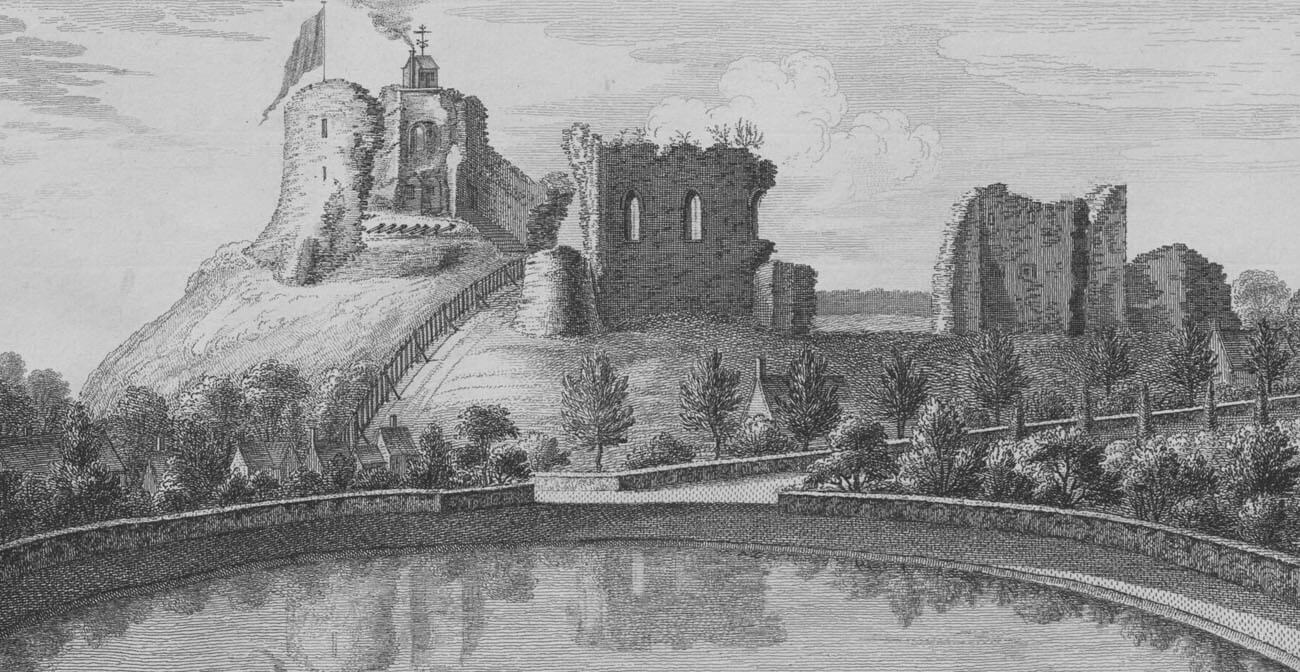

To this day, the lower part of the keep (two storeys without wooden ceilings), fragments of defensive walls and a part of the wall of the building of the great hall with two Gothic windows have been preserved. The remaining elements of the castle have survived only at the level of foundations or slightly higher elements.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, II County of Flint, London 1912.