History

The castle was built on the order of the English King Edward I, at the beginning of the First Welsh War. In 1277, English troops marching along the coast of North Wales quickly defeated the Welsh Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and occupied the entire territory east of the Conwy River (Welsh: Perfeddwlad). To consolidate his victory, Edward founded castles in the most importent locations, the task of which was to keep the areas of North Wales in obedience. Builth was the first of these, then began to fortify Aberystwyth and Flint, founded on the banks of the River Dee, just a few days’ march from the royal city of Chester. This area was devoid of defensive hills, but access to the sea was important to the English, which ensured the possibility of safe and quick delivery of supplies.

Construction of the castle was carried out at a very rapid pace. By the end of July, within a week of the army’s arrival, 1,850 workers had gathered in the Flint region. This number had increased to almost 2,300 by the end of August, while many were brought in under armed guard to prevent desertion. The workers included some 1,800 diggers (‘fossatores’), while the remainder were skilled carpenters and stonemasons. Among them were experienced carpenters who had come from as far away as the Fens, emphasising the importance of the fortifications, and probably also of the navigable canals and quays (‘pontes’) to which building materials were transported from Cheshire and the Wirral Peninsula. The work was supervised by Richard L’Engenour, but the site was also visited by King Edward’s chief master builder, the Savoyard James of St. George. Perhaps the planning of the castle, modelled on French structures such as the Aigures Mortes, was influenced by the observations of the King himself, who had spent some time in France during the Crusade.

The bulk of the army within a month of taking Flint had moved further west, where from late 1277 the priority was to build the advanced castle at Rhuddlan, although the work at Flint was still considered important. In 1279 payments included the stonelaying of the moat (“murifosse castri”) and the completion of the towers, by purchasing lead for their roofs (“ad turres cooperiend in eodem castro”). With work at Rhuddlan now well underway, Flint once again found itself in the spotlight. After a season spent building accommodation for the masons, preparing the lime kilns and quarrying stone, in 1281 efforts were co-ordinated on completing the curtain walls. A year later the main construction work at Flint was sufficiently advanced for English colonists and traders to be brought into the castle borough. In 1285, the royal treasury no longer incurred any expenses for the construction of the castle; only in 1286 carpenters and blacksmiths were engaged in finishing work on the roofs, windows, doors and the construction of a bridge between the castle and the town.

Five years after construction began, the castle was already strong enough that Welsh forces under the command of Dafydd ap Gruffydd, brother of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, were unable to successfully conduct a siege during another war against English rule. In 1294, Flint was attacked again during Madog ap Llywelyn’s revolt. This time, the castle commander, William de la Leye, who was also mayor of Flint, was forced to set fire to the town to prevent its capture by the Welsh. The damage to the town took quite a long time to repair after the fighting had ended, as at least 73 houses had been burnt down. The castle itself was certainly in good condition by 1311, as it hosted King Edward II. A little earlier, in the years 1301-1303, when Flint was in Edward’s possession as Prince of Wales, the castle keep was raised by a storey of wooden construction (“carola lignea nobilis et pulchra”).

The castle was maintained in good condition during the 14th and 15th centuries. Regular expenditure on repairs was recorded in the chamberlains’ accounts for the years 1328-1352 and 1422-1437, including the renewal of the palisade (“jarellum”) of the outer bailey in 1328. The single largest investment related to defence was the building or repairing of the parapet (“alara”) of the defensive wall in 1338. Then, in 1382-1383, a new hall was built in the castle, where the royal judges could be heard, and in 1452 another unknown hall and chamber were founded in the upper ward or in the outer bailey. In contrast, the neighbouring town had already begun to decline in the 14th century, eventually losing about half of its population by the end of the Middle Ages.

In 1399, King Richard II stayed in the castle, but he was a prisoner, held by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby, the future Henry IV. Two years earlier, Richard had banished Henry from the country and then seized the estates of his uncle, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Henry took advantage of the king’s involvement in the campaign in Ireland and returned in 1399, organising opponents of the ruler. One of them, Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, helped capture Richard and transported him to Flint, where he was forced to abdicate. He died shortly afterwards in prison at Pontefract Castle, either murdered or starved. Shortly afterwards, in the early 15th century, Flint Castle once again proved importance during the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr. The 1403 attack destroyed only the town, and the stronghold remained uncaptured until the rebellion was defeated in 1408.

Like many Welsh castles, Flint fell into disuse from the mid-16th century. An survey between 1618 and 1624 revealed that three of the castle’s towers were in ruins, while the keep provided no protection from the rain. Despite this, during the 17th century English Civil War, the castle was garrisoned by Royalist forces as a fortified post against Chester. Because of its strategic importance, it changed hands twice between 1643 and 1645. It was finally captured by Parliamentary forces in 1646, after a two-month siege. To prevent its reuse, the castle was destroyed by Parliament, except for the keep, which was to be used as a prison. In 1652, it was recorded that the town of Flint was largely deserted, while the castle was in a state of complete ruin. Much of it was demolished in 1784-85 to make way for the construction of the early modern county gaol.

Architecture

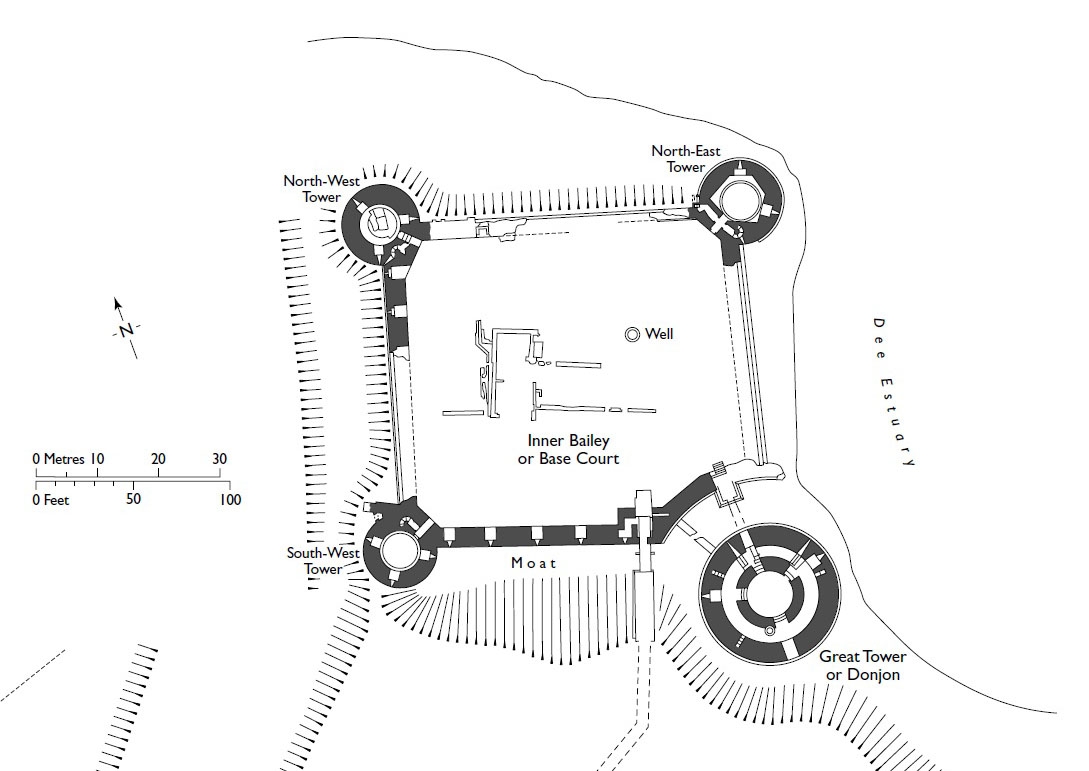

The castle was built on a rocky base, jutting out towards the wide mouth of the River Dee into the Irish Sea. It was founded on a plan close to a quadrangle, which was protected from the north and east by the waters of the river, and from the other sides surrounded by a moat connected to it. The moat, about 350 meters long, stretched around the mainland part of the castle, turning its area into an island. The ditches were partly carved into the rock, and partly dug into the red-brown clay and other alluvial deposits of the lower slopes of the headland. The excavated material was used to level the sandstone and raise the ground by about 2 meters, thanks to which, after the preparatory work was completed, a raised platform was created for the core of the castle and the outer bailey on its southern side. The mainland area of the castle near the coast was covered with salt marshes, additionally strengthening the protection of the entire complex.

The main part of the castle was surrounded by four straight curtain walls and one section of a rounded wall, defining a courtyard measuring approximately 54 x 48 meters. Three corners were reinforced with cylindrical towers connected by straight sections of wall, while the fourth, south-eastern corner, was distinguished by a cylindrical keep separated from the perimeter, placed in front of a specially rounded section of wall. Such an unusual layout for Edwardian castles could have been inspired by the fortified town of Aigures Mortes in France, and specifically the Tower of Constance (French: Tour de Constance). The location of the keep allowed both to flank the entrance gate to the castle on the western side and to dominate the outer bailey and the boat landing located to the south. The massive keep tower was the safest place in the castle, protected from the east by the river, and from the other sides by the moat and walls, without which it was basically impossible to storm the keep. Only in Flint, among all of Edward I’s Welsh castles, was the keep situated outside the defensive perimeter of the castle core, but the idea of an isolated point of resistance, combining residential and defensive features, was later repeated at Raglan Castle.

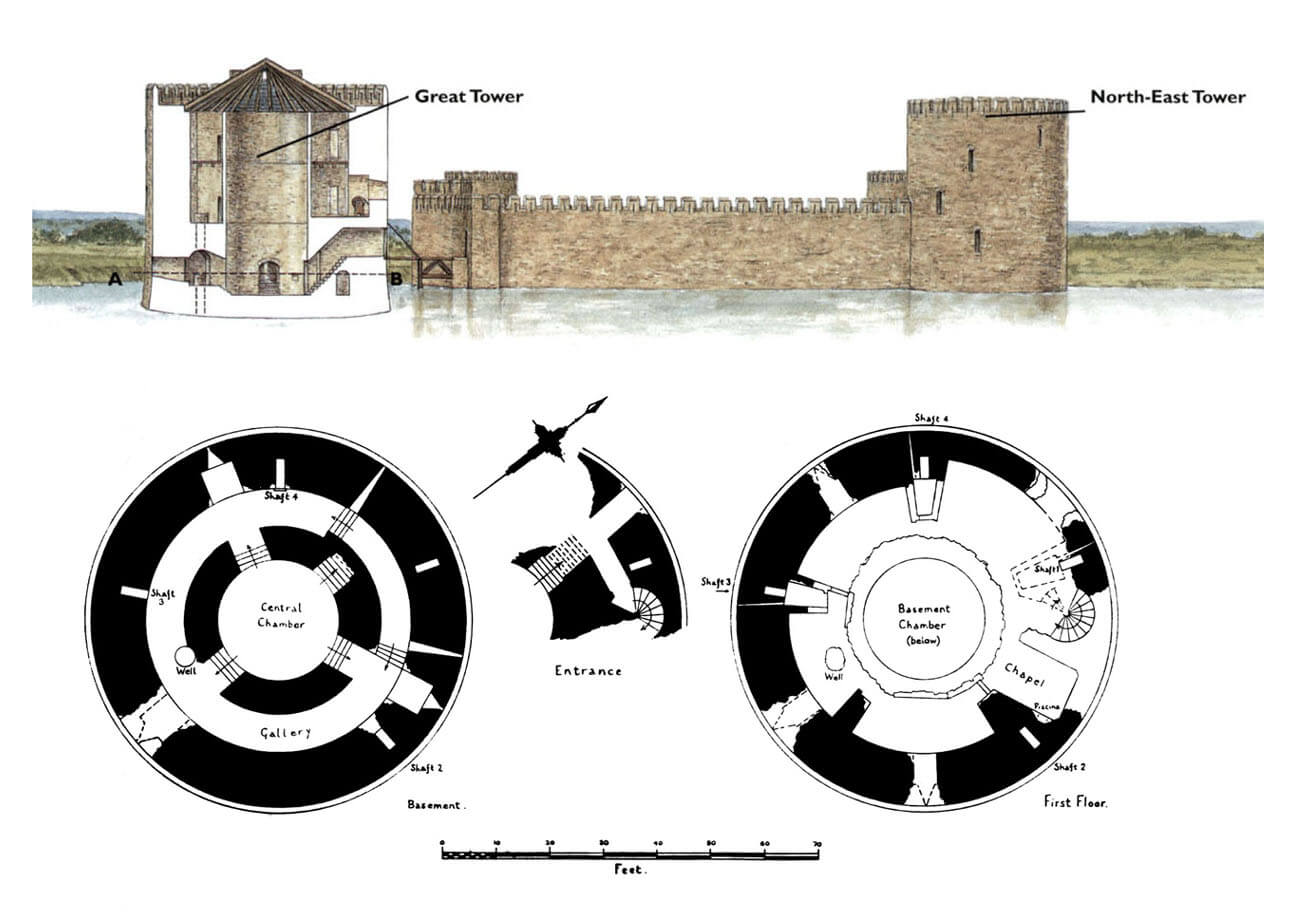

The massive keep had a diameter of about 20 meters. It was formed by walls with a thickness of as much as 7 meters at the ground level, and up to 5 meters wide above, with the thickest part of the base gaining slightly sloping external elevations (batter). The vertical walls above were pierced only by slit, splayed inwards openings and small ventilation holes. The tower’s crowning may initially had the form of an unroofed, circumferential wall-walk, surrounding the conical roof of the top floor and hidden behind a battlemented parapet. At the beginning of the 14th century, the tower was raised by an additional wooden structure, perhaps in the form of a hoarding porch around the parapet or possibly an entire additional floor.

The keep was accessible only by a drawbridge, placed on its northern side, facing the courtyard of the main part of the castle. It did not have a portcullis, which was unusual in Anglo-Norman buildings of this type. Beyond the bridge and a short passage in the thickness of the wall, steps led down to a central room 6 meters in diameter, and then to a surrounding, vaulted gallery, provided with three arrowslits and also with small ventilation openings. The gallery surrounded the central room, to which it was connected by three doorless passages, each with three steps leading down. This was a unique solution, in addition to providing access to arrowslits, facilitating communication during sieges and fights. The central space was only indirectly lit by the three arrowslits, placed on the extension of the transverse passages. At the very bottom of the room, there was a well, above which there was a hole in the ceiling, allowing water to be supplied to the upper floors. The crew could get to the upper floor via a spiral staircase, accessible from a side corridor in the entrance passage.

On the first floor of the keep there were five rooms, accessible from the centre of the tower and connected with each other. The smallest of them was a rectangular chapel oriented towards the east, with a piscina in the southern wall. The remaining rooms had a plan with segmental external walls, due to their location at the perimeter of the tower. It were not heated and so poorly lit that could not serve as dwelling for people of higher status, but the placement of three latrines allowed the garrison to stay inside. Vertical channels in the walls, with outlets facing the moat, were used to clean the latrines. Above the floor there must have been at least one more, third floor, connected to the others by a wide spiral staircase and equipped with latrines, the channels of which were also directed to outlets in the lower part of the tower. It is possible that there were more comfortable living quarters inside.

The moat in front of the castle was probably faced with stones, which replaced the original turf reinforcements, but were removed during an attempt to widen the ditch in the 15th or early 16th century. The moat at the front of the castle was about 7 meters wide at the top and 5 meters wide at the more or less flat bottom. Its depth was about 5.5 meters from the surface of the outer bailey. The bottom of the moat was about 2 meters below the high water level during the spring tides, so it was partially flooded or saturated, although there was no system for maintaining a constant water level or protecting against sporadic tides. Interestingly, the moat was probably never cleaned. Perhaps the knee-deep, damp and boggy mud was considered a greater obstacle than the waist-deep water on the hard bottom.

The castle’s defensive walls were as much as 3 meters thick at ground level. It were built of cut, evenly layered yellowish stone, with two horizontal strips of two layers of red sandstone in the western curtain wall. This was probably a deliberate choice of colour, prefiguring the decorative technique that was later used at Caernarfon Castle. The lower part of the curtain wall, up to a level of about 5 meters, was characterised by a slight inclination, above which the walls were vertical. In the thickness of the walls at ground level, deep, semicircular and slightly pointed recesses were created on the side of the courtyard, containing splayed inwards arrowslits. Some of these embrasures were modified in the late medieval period by the construction of small stone platforms at their bases and blockades inserted in the lower part of the slits. Round holes were punched in the upper sections to create inverted key loop holes.

The corner towers were about 12 meters in diameter and almost completely protruded in front of the perimeter of the fortifications, providing good opportunities for flanking fire. Their two highest floors were occupied by residential chambers equipped with latrines, fireplaces and very narrow windows, while the lowest floors were unlit warehouses accessible through openings in the ceiling. It were entered from the middle floors, accessible from the courtyard by means of a few steps. These middle floors, apart from the defensive wall-walks crowning the towers, were combat levels, equipped with two or three arrowslits. Communication between the upper floors was provided by spiral staircases, embedded in the thickness of the walls and accessible from the entrance passages of each tower. Most of their rooms were cylindrical, only the upper rooms of the north-eastern tower were polygonal. The castle courtyard development initially consisted only of wooden buildings, attached to the inner elevations of the defensive walls. The stone rooms in the middle of the courtyard were probably built only in the later Middle Ages.

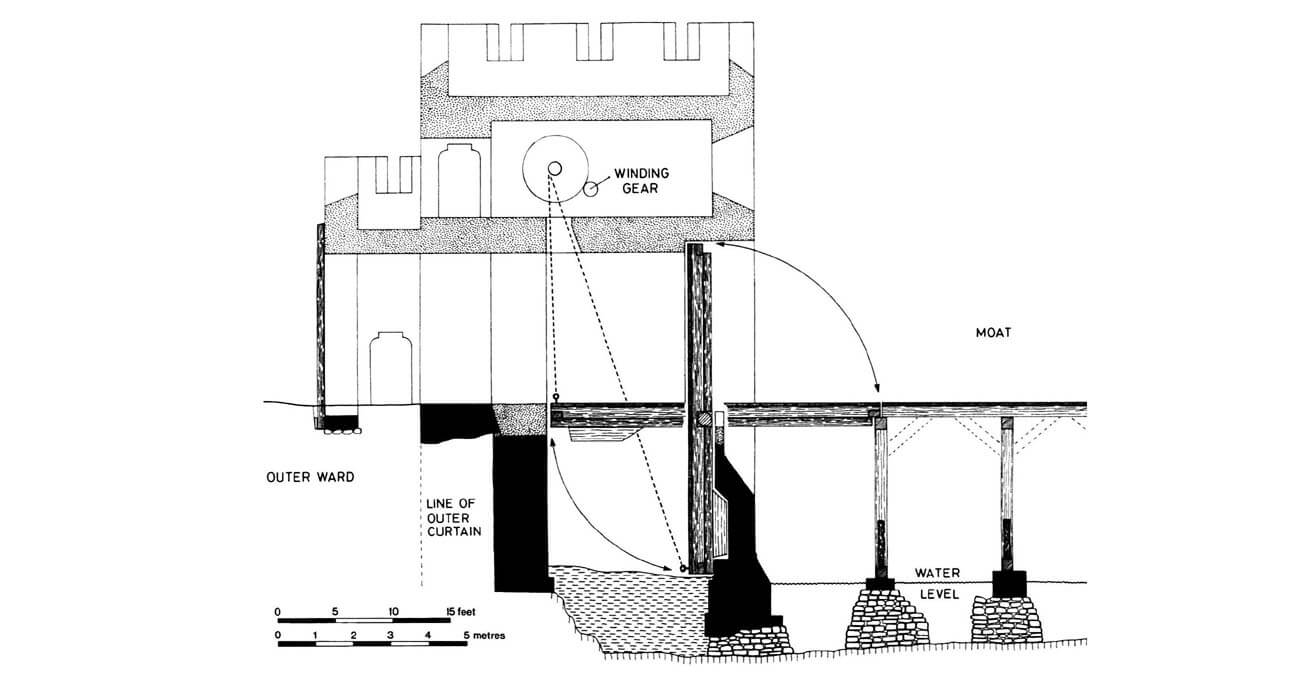

The entrance to the upper ward was located in a small gatehouse, located in the eastern part of the southern curtain wall. It was located entirely inside the perimeter and did not protrude from the face of the defensive wall. Only the wooden hoarding above the passage could have protruded towards the moat. The gate passage itself was protected by double-winged gates, a portcullis and a drawbridge, and was also flanked by a small guard’s room on the western side. The drawbridge probably operated on the principle of counterweight, which meant that its rear part was retracted down when the front part was raised. The gate led through the moat to the outer bailey with a stone wall, while from the east it was controlled by a massive keep, and from the west by a south-western corner tower.

The outer bailey was surrounded by a 2.4 meters thick stone wall from the south and in the southern parts of the eastern and western sections, while on the other sides it faced the moat only by a weak 0.8 metre-thick wall and probably in some sections by an ordinary palisade. The outer bailey was also protected by the waters of the River Dee and an outer moat 26-30 meters wide, crossed by a wooden bridge supported by stone pillars. In the front part, the outer bailey moat ran about 2 meters from the curtain walls. In the east, it moved away slightly, to about 7 meters at the corner, where the castle dock operated and the moat connected with the river. Like the inner moat, the moat surrounding the outer bailey was faced with ashlars of evenly worked stone. The defensive wall of the outer bailey was made of roughly hewn, grey sandstone blocks set in pale yellow mortar. Its masonry was of slightly worse quality than that used in the upper ward walls

The entrance to the outer bailey was provided by a quadrangular gatehouse in the southern curtain wall, with most of its mass projecting into the foreground towards the moat. Its front wall extended in front of the ends of the side walls, creating a pair of flanking buttresses that were to take the pressure of the gate arch, equipped with a drawbridge. This bridge probably operated on the principle of a rotating counterweight, so its rear part was lowered down while the front part was raised and the passage was blocked. The mechanism operating the bridge must have been located on the first floor of the building, which was most probably connected to the wall-walk in the crown of the curtains. There must also have been latrines on the first floor, the drains of which were placed at an angle in the corners between the side walls of the gate and the front walls of the curtain wall. The entrance to the first floor of the gatehouse could have been in one of the two quadrangular turrets, added around the beginning of the 14th century to the gate from the side of the courtyard, where they flanked the rear part of the passage, 2.4 meters wide. Each turret had internal dimensions of 2 x 1.5 meters. Two posts were placed at their external corners, on which double-winged gates could rest, bolted in case attackers broke through the drawbridge.

The courtyard of the outer bailey for most of the Middle Ages was probably an open and even space with a small number of buildings. It was clearly adapted for gathering troops or military supplies, while small wooden or half-timbered houses for economic purposes could be set against the defensive wall. In the 14th century, a new road was marked out between the two gates through the courtyard of the bailey, about 10 meters wide, surrounded on both sides by gutters 1 meters wide and 0.6 meters deep. The surface of the road was paved with crushed sandstone to harden it, but the side gutters were prone to silting up and probably quickly became clogged with waste. In the north-eastern part of the castle ward there could have been a small harbour or boat landing, accessible through a postern in the length of the thinner wall.

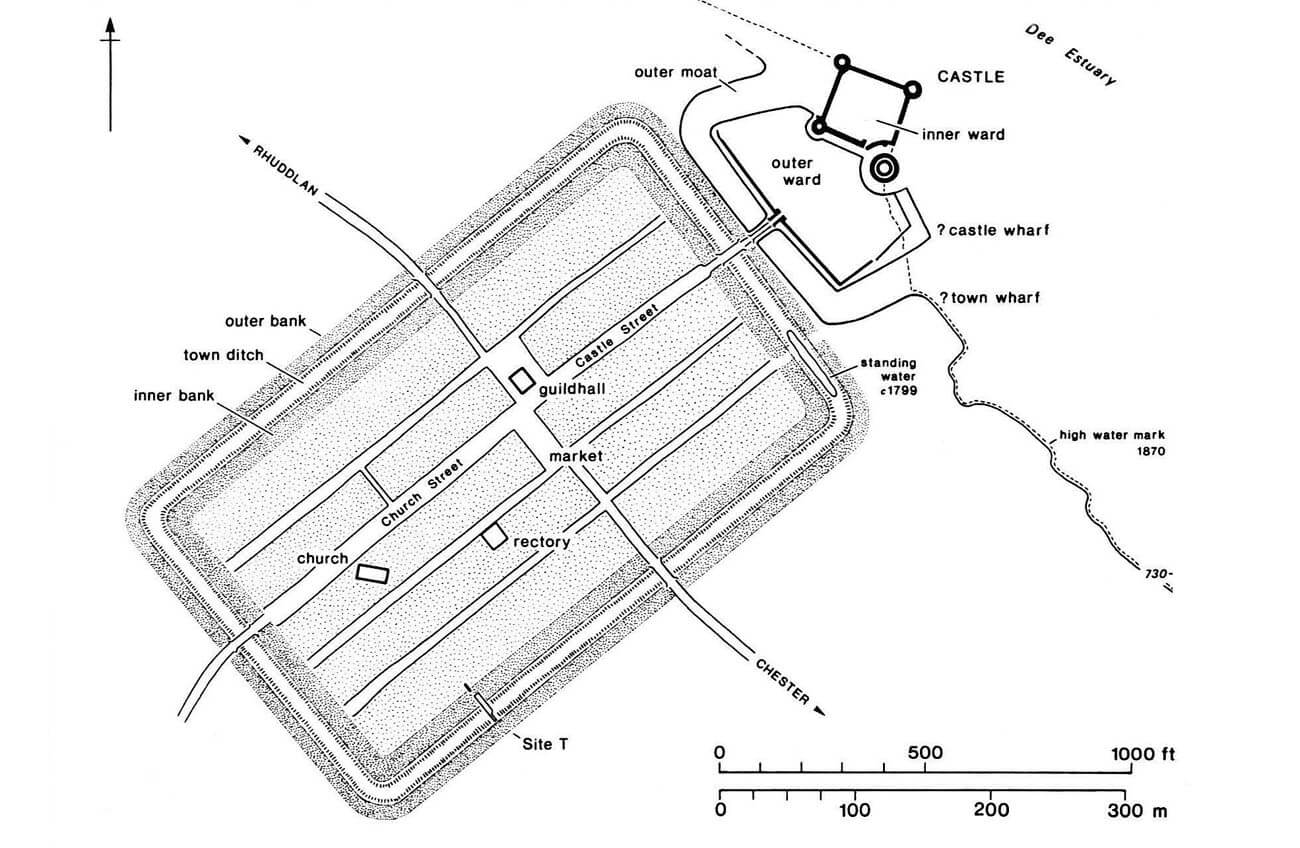

To the south-west of the castle stretched a small town, founded on a relatively flat, open area, which allowed for the creation of a regular rectangular layout measuring approximately 420 x 250 meters. The town was surrounded only by wood and earth fortifications with a ditch and a doubled perimeter of ramparts. The ditch was approximately 16 meters wide and 3 meters deep, with sloping sides and a flat bottom approximately 5 meters wide. Its outer slope was covered with hard, red-brown clay, while the bottom silted up throughout the Middle Ages. The outer rampart probably secured the town only with an earthen embankment, while the inner one could have been reinforced at a height of approximately 3 meters with wooden fortifications in the form of a palisade, behind which ran a wall-walk. The width of the base of the inner rampart was approximately 17 meters. From the inside it sloped gently towards the town, while from the outside it had a steeply formed slope..

Current state

The castle has survived to this day in the form of an advanced ruin. Visible are the remains of three corner towers in varying degrees of preservation, relics of the gatehouse, fragments of defensive walls of incomplete height and a keep preserved to the height of the first floor. The defensive walls have survived in the best condition in the southern section and in the northern part of the western section, where several niches with arrowslits are visible. In the area of the outer bailey, only a low fragment of the western defensive wall has survived. The castle’s surroundings have also changed drastically, due to the lowering of the water level, the withdrawal of the shoreline and the planting of a small forest on the western side. The castle is available for sightseeing free of charge, including the possibility of entering the keep.

bibliography:

Gravett C., The Castles of Edward I in Wales 1277-1307, Oxford 2007.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

King D.J.C., The Donjon of Flint, „Journal of the Chester and North Wales Architectural, Archaeological and Historic Society”, 45/1958.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Miles T.J., Flint: Excavations at the Castle and on the Town Defences 1971-1974, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 145/1998.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Simpson W.D., Flint Castle, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 95/1940.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.