History

The Norman church in Ewenny was built in the 1120s, from the foundation of William de Londres, the lord of Ogmore Castle, which before 1141 his son, Maurice de Londres, granted to the Benedictine Abbey of St. Peter in Gloucester. At that time, a seat for twelve monks and the prior was established in Ewenny, around which the settlement of Ewenny grew soon after. Its population treated the priory church as a parish, only the chancel and transept were reserved for monks, who built stone claustrum buildings next to it until the 13th century.

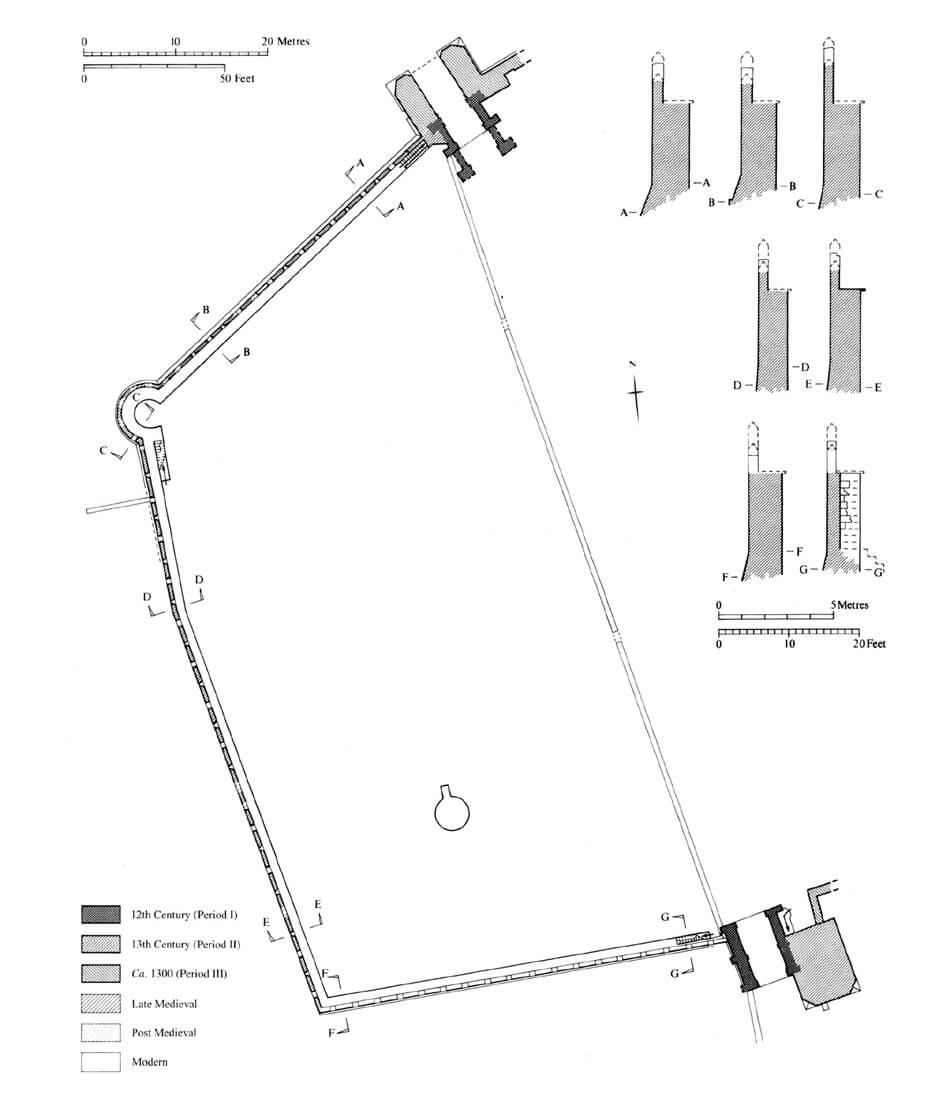

The priory was fortified quite early, already in the 12th century, in order to protect it against Welsh armed attacks. The fortifications were staffed by a permanent garrison, originally watching over two stone gatehouses and wood and earth fortifications. In the mid-thirteenth century, it were expanded with stone curtains of the walls and a horseshoe tower, and at the beginning of the fourteenth century, they were rebuilt once again, although this time it seems that prestige had more considerations than just defense. The gatehouses were strengthened and a new four-sided towers were added than. Edward I used the man at arms from Ewenny in his attack on Wales in 1284, and Henry IV used Ewenny as a base to attack Coity Castle during the rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr in 1405. Apart from the rise of Glyndŵr, the 14th and 15th centuries, however, was usually a peaceful period in Wales.

In 1284, Archbishop Pecham paid a visit to the monastery. The audit revealed poor management and poor financial condition in Ewenny. He ordered more stringent controls and entrust the functions of treasurer to three monks. He also admonished the monks for using food properly, that they did not consume. He stated that it should be given to the poor and not to family members or dogs. He reminded monks that they should not eat meat and should keep silence according to the rule as well as keep in mind their obligation to give alms to the poor. The valuation of the priory seven years later amounted to just over £ 56 of annual income, supplied mainly from appropriated churches (Ewenny, St Bride’s Major, Colwinston, Oystermouth, Pembrey, and St Ishmael). Still more difficult times came in the fourteenth century due to the onset of the plague and the end of the family of founders and patrons, the de Londres. At the beginning of the 15th century, the monastery’s property suffered considerable damages during the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, probably because the prior helped organize a defense against the Welsh.

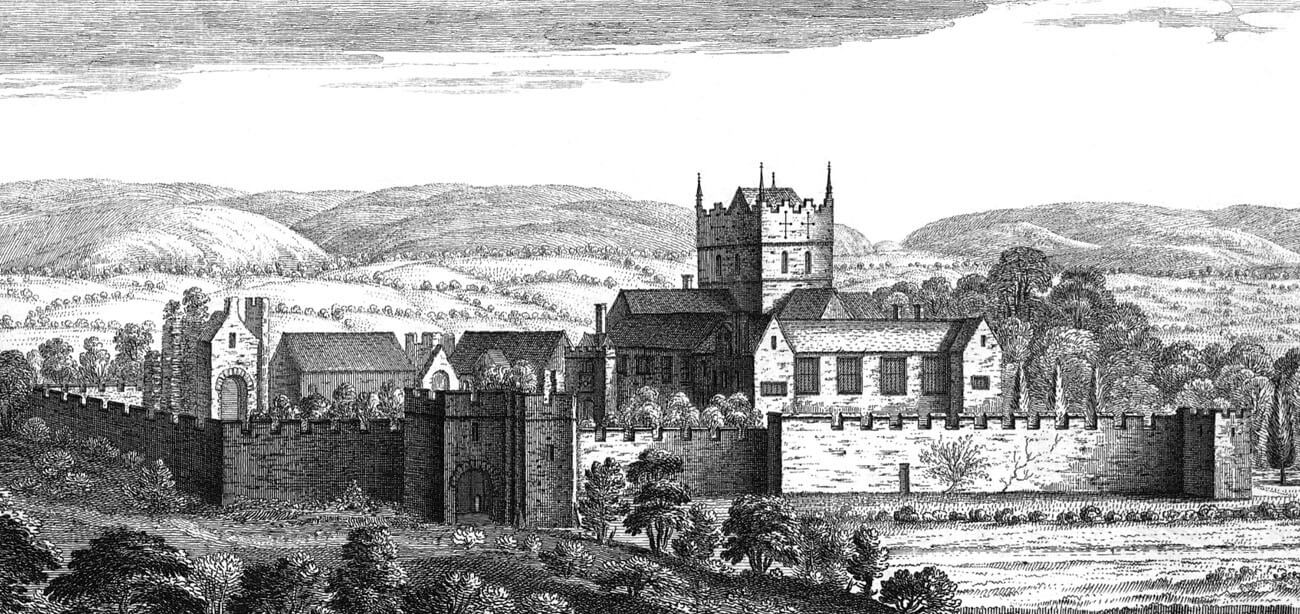

The monastic community was dissolved in 1536 and, in the same year, rented to Sir Edward Carne. In 1545, he bought monastic buildings along with its belongings and transformed them into a residence, although the temple still served as a parish church. At the end of the 17th century, the estate passed into the hands of the Turbervill family, and in the nineteenth century, the estate was taken over by Colonel Thomas Picton-Warlow and then his heirs. In 1803, the northern transept and side chapels of the church were destroyed, the ruined eastern wing of the former claustrum was also demolished.

Architecture

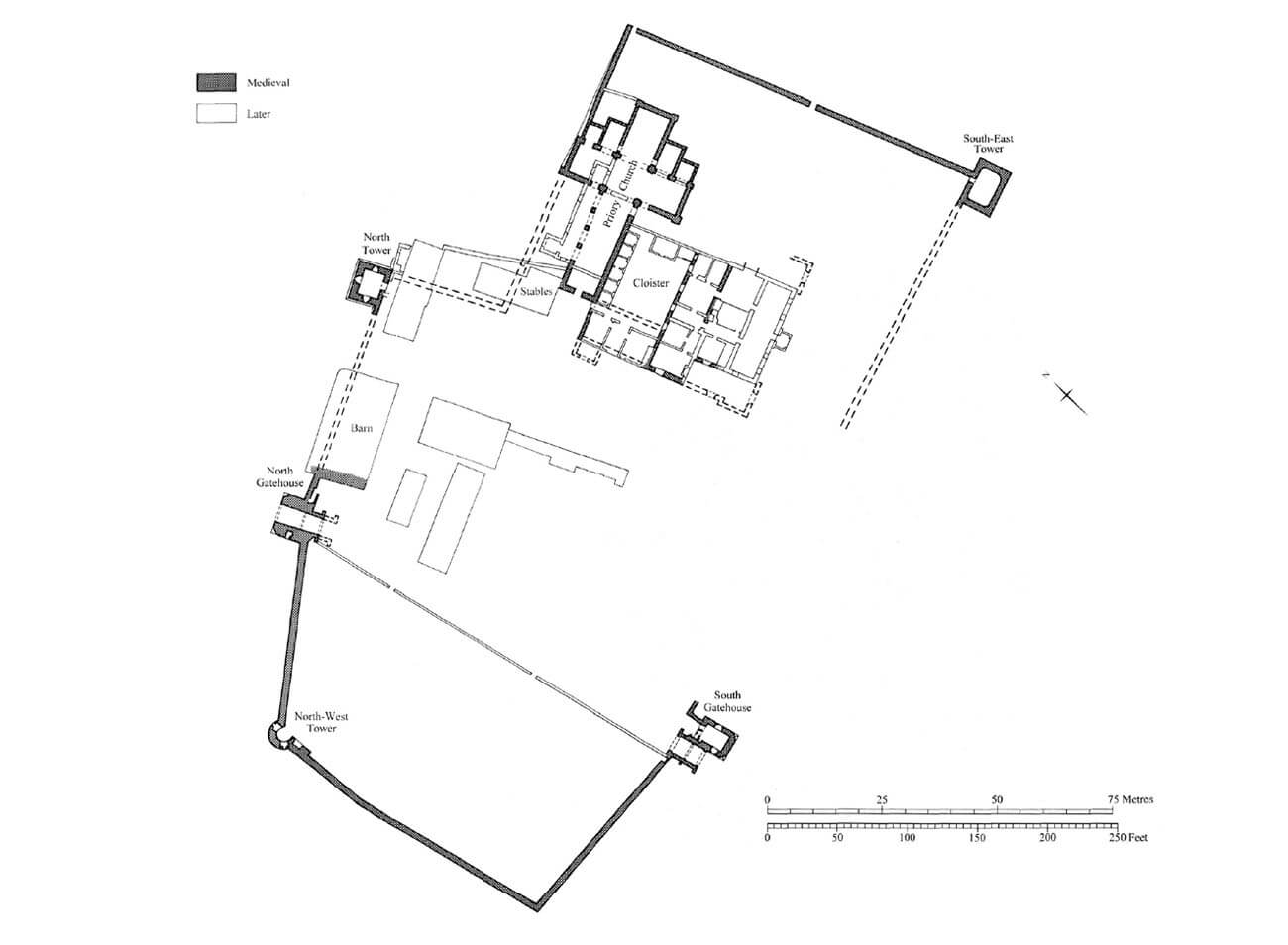

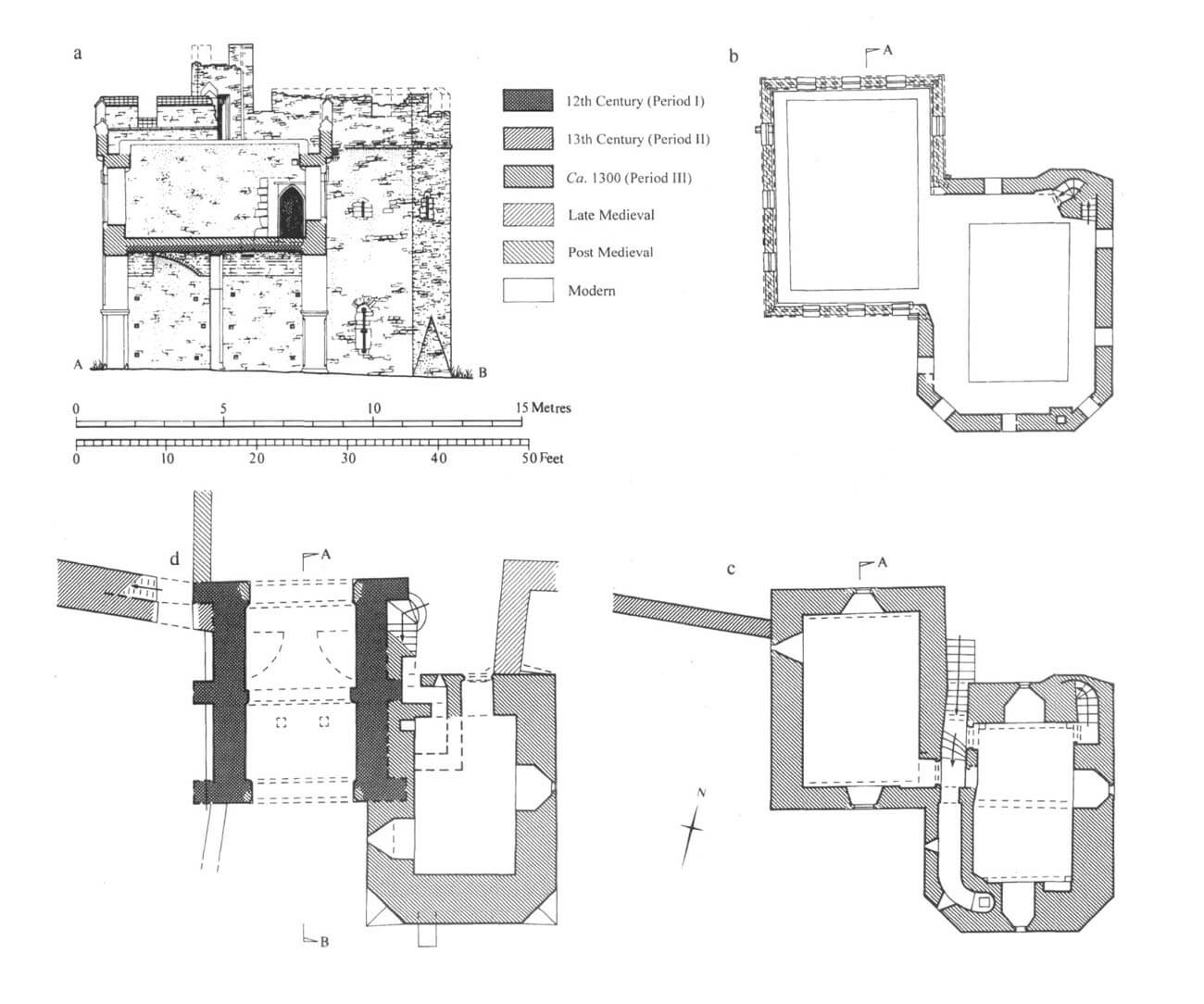

The priory was built on a flat land, south of the Ewenny River, not far from Ogmore Castle to the west. It was surrounded by a defensive wall on a square plan of 173×118 meters and a length of about 550 meters, reinforced with four towers and two four-sided gatehouses, located on the north and south sides. The fortifications were stronger on the north side, where the main road from Ogmore Castle ran, connecting with the river bridge on the east side. The defensive wall was distinguished by a battered, oblique plinth and battlement with arrowslits pierced in melons, access to which was possible from the defensive wall-walk created at the top of the wall. The height of the wall to the level of the wall-walk was from about 3.5 to 4.2 meters, and an additional 1.5-2 meters high was provided by a breastwork. The wall was probably preceded by a ditch along its entire length.

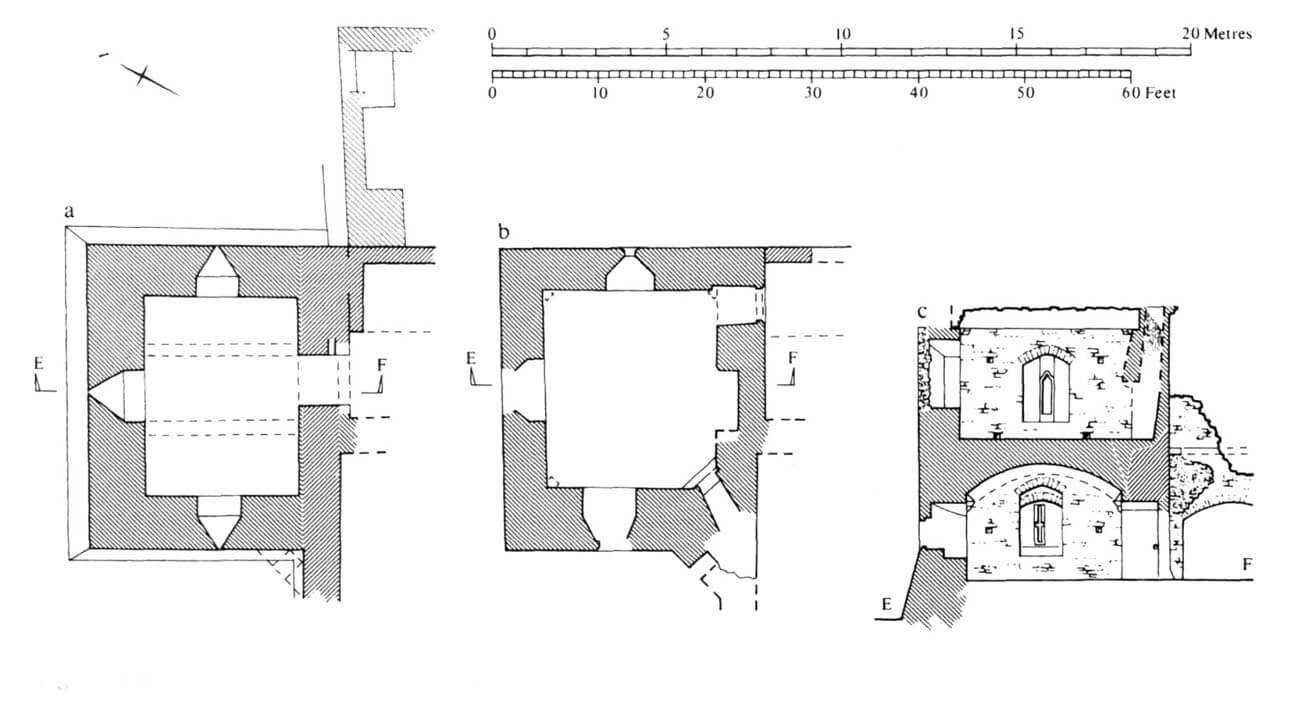

Three of the towers strengthened the corners of the defensive perimeter, two of them (north and south-east one) were erected on a square plan, and one (north-west) on a horseshoe plan, open from the inside. The fourth tower was originally to be located in the wall bent above the western part of the monastery church. The 13th-century horseshoe tower was not very protruding in front of the perimeter, so its possibilities of flanking the side curtains were limited, and the two cross-shaped arrowslits in the lower floor were directed more towards the foreground. Slightly higher than the curtains, tower was topped, like the wall, with a battlement, reaching 2.8 meters above the level of the defenders wall-walk. Dating from the beginning of the fourteenth century, the four-sided northern tower housed two rooms, one in the ground floor and one on the first floor. The lower one was accessible by a portal directly from the courtyard, covered with a barrel vault with two arch bands and equipped with three arrowslits, one on each side except the south one. The upper room had a residential function. It was accessible through a narrow passage from the level of the wall-walk, in the corner also connected to the latrine. It was equipped with a fireplace and two single-light windows to the east and west. The north window could have been larger, two-light. The northern tower could originally be covered with a hip roof, which would be indicated by corbels placed in all corners. A two-story south-east tower from the same period probably had a similar, two-story form.

The gates to the priory, located on the north and south sides, were originally four-sided gatehouses with two-bay passages, reinforced with external buttresses, which would indicate that they were originally adjacent only to wood and earth fortifications. They were rebuilt at the beginning of the 14th century, when older simple gatehouses were included in newer buildings. The northern gate was extended to the outside by one massive bay, but the rear part was shortened, while the southern gate was secured with a four-sided gate tower, or actually a second gatehouse, because both structures were of comparable height. After the reconstruction, the gates were characterized by spurs – buttresses typical for Wales, similar to those used in Llandaff, Caerphilly or Kidwelly (Chapel Tower).

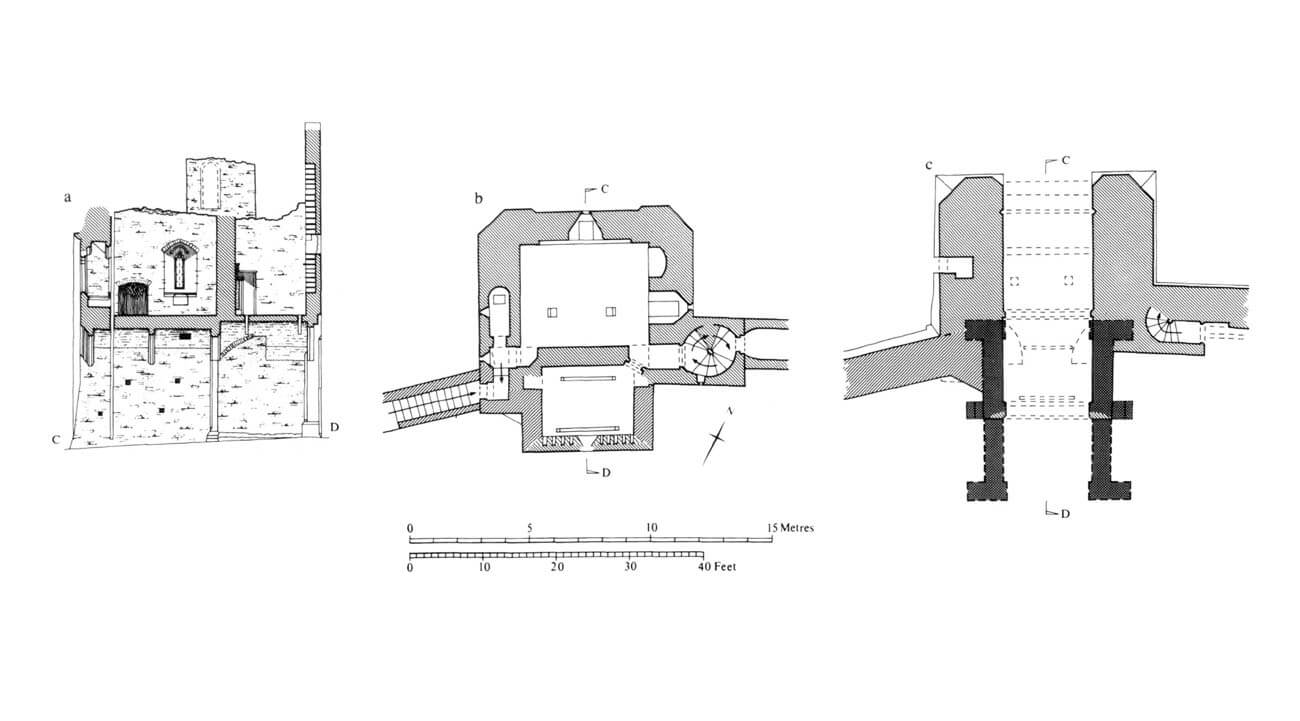

The southern gate had a semicircular vaulted passage, in the front bay pierced with two four-sided loopholes, the so-called murder holes and closed with double-leaf gates. The lack of a portcullis could have contributed to the poor protection of the passage. An extension in the foreground flanking main gatehouse, in the ground floor had a room accessible through a pointed portal, equipped with two splayed openings: one topped with a trefoil, facing east, and the other one, loop hole, facing west (towards the entrance to the gate). In addition, in the thickness of the north-west wall there was a latrine, connected by a canal with an outlet directed to the south towards the moat. The first floor of the extension had to have a bold north-eastern corner suspended on corbels to accommodate the stairs leading from the first floor to the highest, open combat floor (protected by battlement). The first floor was illuminated by three single-light windows closed with trefoils, set in deep recesses crowned on the inside with segmental arches, while heating was provided by a fireplace at the southern wall. The second, external stairs led from the courtyard to the north-west corner, where separate passages ensured a connection both with the first floor of the adjoining extension and with the room above the gate passage. Straight ahead, it led to a long corridor in the thickness of the wall, lit by two small openings and housing a latrine at the end. The room above the gate passage was originally illuminated from the north and south by single-light openings topped with trefoils (during renovation, one of them was equipped with medieval cinquefoil jamb, transferred from another part of the priory) and a loop hole facing the west, where it could flank the curtain of the defensive wall. The gatehouse was crowned with two gable walls mounted on corbels and a gable roof with a ridge on the north-south line.

The northern gate, which was the main entrance to the priory area, was the strongest element of the fortifications, although not without simplifications and deficiencies. Its front part, added in the fourteenth century, protruded in front of the curtain of fortifications with two massive walls 2.6 meters thick, between which a gate passage was led, then transforming into one of the 12th-century bays. There were no towers flanking the passage and no loop holes from the side guard chambers. Moreover, the outer façade was not pierced with any arrowslits, but only on the upper floor with a narrow window topped with a trefoil. The passage itself was vaulted, equipped with two murder holes, a portcullis 0.7 meters from the facade, and a double-leaf gate. The first floor of the gatehouse was accessible through a pointed portal in a turret with a cylindrical staircase on the eastern side. At the first floor, the stairs opened onto a small vestibule, right in front of the wall that divided the floor into two rooms. The smaller southern one was illuminated by a single window from the south and the western opening partially blocked due to rebuilding. The larger northern one, where the murder holes were located and where the portcullis was operated, was illuminated by the aforementioned northern and eastern windows. Both were topped with trefoils and had side stone seats in deep recesses. In the eastern wall there was additionally a fireplace, and in the thickness of the western wall, a passage connected with a latrine on one side and a curving corridor leading to the wall-walk of the curtain. The eastern staircase also provided the possibility of entering the upper combat storey, originally protected by battlement, while the stair turret itself was higher than this storey, reaching the form of a small guard-warning platform.

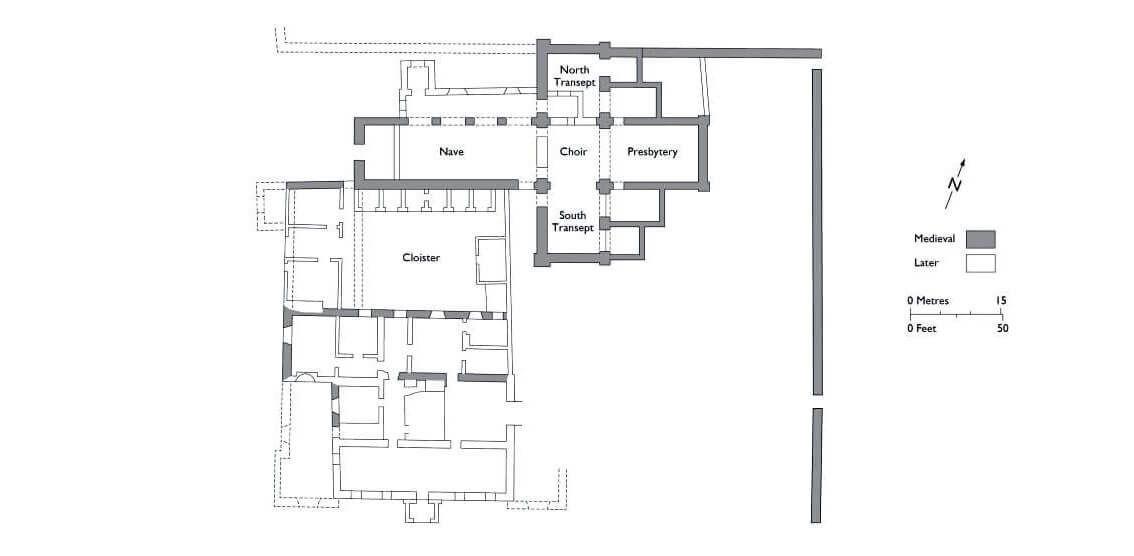

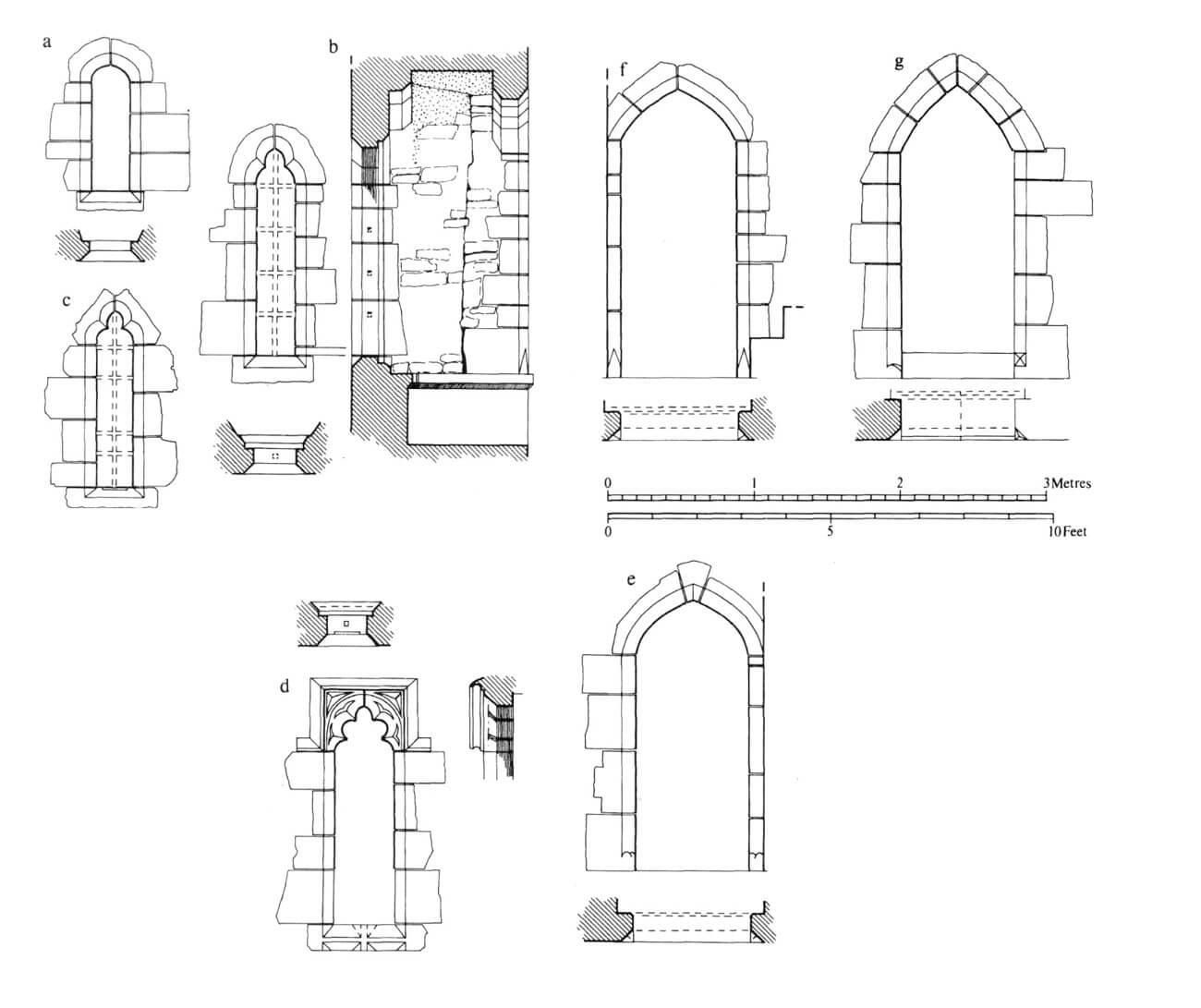

The Romanesque priory church in its final form had the shape of a building on a Latin cross plan. It consisted of a single, five-bay nave, the northern and southern transept, a four-sided tower at the crossing and a rectangular chancel with chapels adjacent to the north and south. On each side, there were two chapels of different lengths, so that the whole had a stepped layout. At the end of the 12th century, the northern wall of the nave was pierced with arcades based on massive cylindrical columns, opening onto the northern aisle.

The main nave was illuminated in the longitudinal walls with narrow, semicircular windows (from the south they had to be above the roofs of the cloister). Similar ones were in the gable walls of the transept (three from the south and two from the north), while on the eastern part of the chancel with the main altar, the sun light through single windows from the north and south and a triad of windows in the eastern wall. This part, the last bay of the presbytery, was distinguished by a cross-rib vault, while the remaining ones were covered with a barrel vault with arch bands. At the height of the window sills, all the presbytery facades were surrounded by a characteristic decorative cornice formed in a chevron pattern, also used partially in the transept. The transept opened with semicircular, stepped arcades to the side chapels, above which there was a room, accessible by a straight four-sided passage. The internal chapels were also connected with the chancel with semicircular openings in the western bay and an unusual diagonal passage through the northern wall. The richly decorated facades of the presbytery and transept contrasted with the severer nave and northern aisle. This was due to the division of the church into the eastern part intended for monks and the western part which served as a parish temple. Both these parts were separated by a rood screen.

The southern side of the nave was adjoined to a patio surrounded by cloisters and monastery three-range buildings with all the rooms required by the rule: a dormitory, refectory, chapter house, and economic buildings. Their exact layout is not known, it can only be assumed that, according to the Cistercian rule, the refectory was located in the southern range, the chapter house on the ground floor of the east wing, and the dormitory on its first floor. The eastern wing was at the line of the southern arm of the transept. Judging by the layout of the portals, its upper floor could be connected to the church by the so-called night stairs used by the brothers who went from the dormitory for night and morning prayers, and by means of a wooden gallery or porch overhang on the eastern façade, so that it was possible to go to the church without disturbing the sleepers. In the west wing, on the first floor, there was the prior’s chamber or a room for guests of the monastery.

Current state

The monastery church has survived until now without the northern transept and its chapels and the western bay of the nave. The northern aisle of the nave does exist, but it is the result of works from the 19th century. The monastery buildings have not survived or have been drastically rebuilt, losing their original stylistic features. The most interesting element are the fortifications visible on the west side of the church, unique in Wales. A large fragment of the defensive wall of a length of about 330 meters, three towers and two gatehouses have been preserved, while the south-eastern tower was converted into a dovecote.

The priory church is an excellent example of Norman, Romanesque architecture. Inside the magnificent chancel you can see a rood screen from the fourteenth / sixteenth century. Only the church is open to visitors, as the remaining buildings remain in private hands and are inhabited. Of course, you can view the monastery’s fortifications from the outside.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Later Castles, London 2000.