History

Dolbadarn Castle was built in the 20’s of the 13th century by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. It had the task of controlling the Llanberis Pass, an area of valuable pastures for animals and a key path to Snowdonia, which was the core of the Gwynedd kingdom. Llywelyn spent most of his life fighting his opponents and ultimately united most Welsh princes under his rule. In addition, he maintained a high position thanks to the key alliances with the Norman marcher lords. To this end, his son Dafydd married Isabella, the daughter of William de Braose, Lord of Brecon. Likewise Llywelyn’s daughter, Helen, married John, later Earl of Chester. Therefore, Llywelyn not only sought to build a modern (as for the then Welsh conditions) castle, but also to create a stronghold of the same prestige that his new Norman allies had.

The death of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth in 1240 caused an outbreak of partitions between heirs and the slow collapse of Gwynedd. English king Henry III tried to take advantage of the situation and, under the Woodstock Treaty of 1247, deprived Gwynedd of control over the lands east of Conwy. In 1255, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (called the Last) defeated his opponents and, by virtue of the Treaty of Montgomery from 1267, was recognized by the English and Welsh as the suzerain of Wales. During this period, he imprisoned his older brother, Owain ap Gruffudd, who would most likely spend almost 20 years in prison at Dolbadarn Castle.

In 1282, on the initiative of Dafydd ap Gruffudd, younger brother of Llywelyn, the Second War of Welsh Independence broke out. Llywelyn himself was killed at the end of 1282 at the Battle of Orewin Bridge, while Dafydd fled first to Dolwyddelan, then to Castell y Bere and ultimately to Dolbadarn. In 1283 he was captured by the English and executed by hanging, drowning and quartering. Dolbadarn was besieged and conquered in the same year.

King Edward I was determined to prevent further revolts in North Wales and began building a series of new castles and walled cities, replacing the old Welsh administrative system with a new one, managed from Caernarfon. The castle in Dolbadarn ceased to matter, and within two years the timber from the stronghold was used by the English to build a castle in Caernarfon. It was both practical and symbolic action, demonstrating Anglo-Norman power over one of the most important centers of Welsh princes.

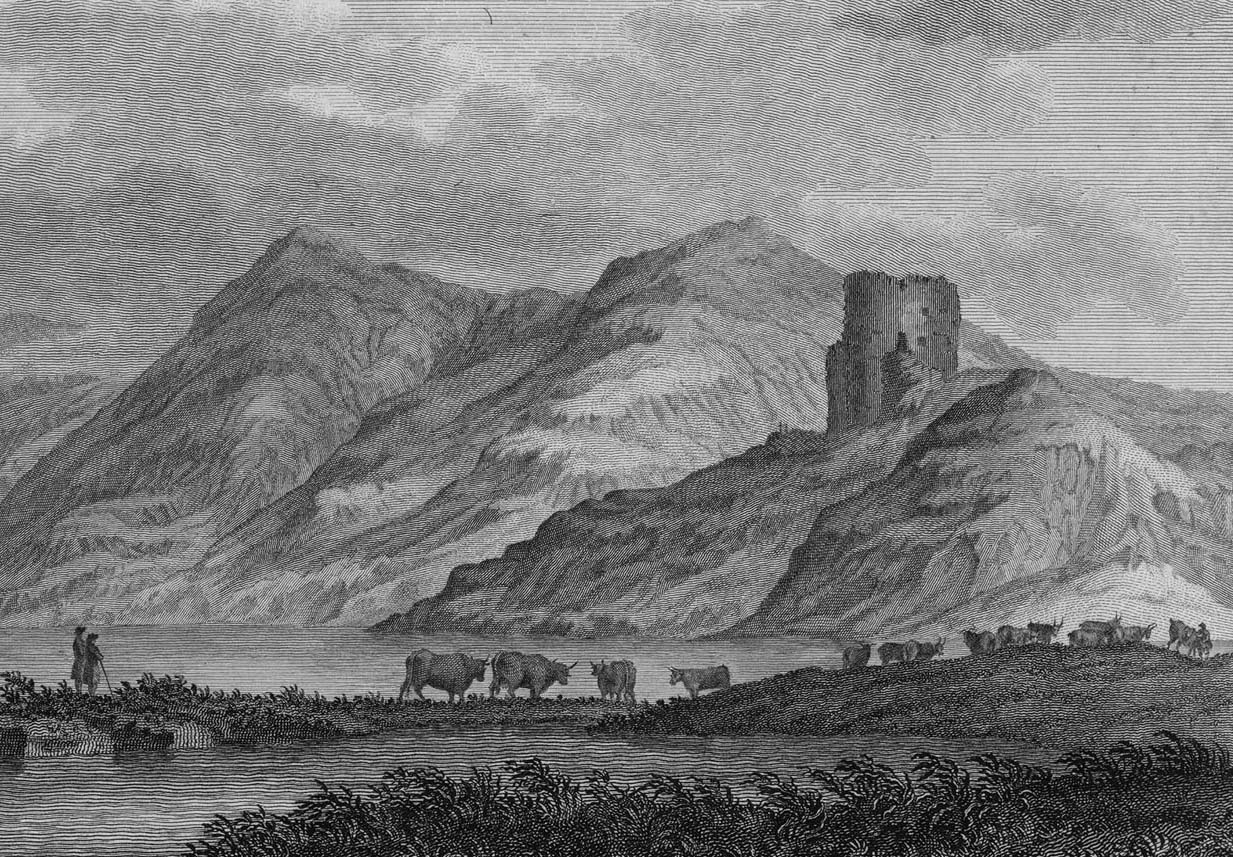

Despite the loss of significance, Dolbadarn remained the administrative center of the royal court, and at the beginning of the 14th century, even small repairs were made. During the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr from 1400, the castle could serve as a prison. However, little is known about the later history of the castle. Probably it served as a private residence, because the external stone stairs of the keep were added no later than in the middle of the eighteenth century. From the end of the eighteenth century, it remained in ruin.

Architecture

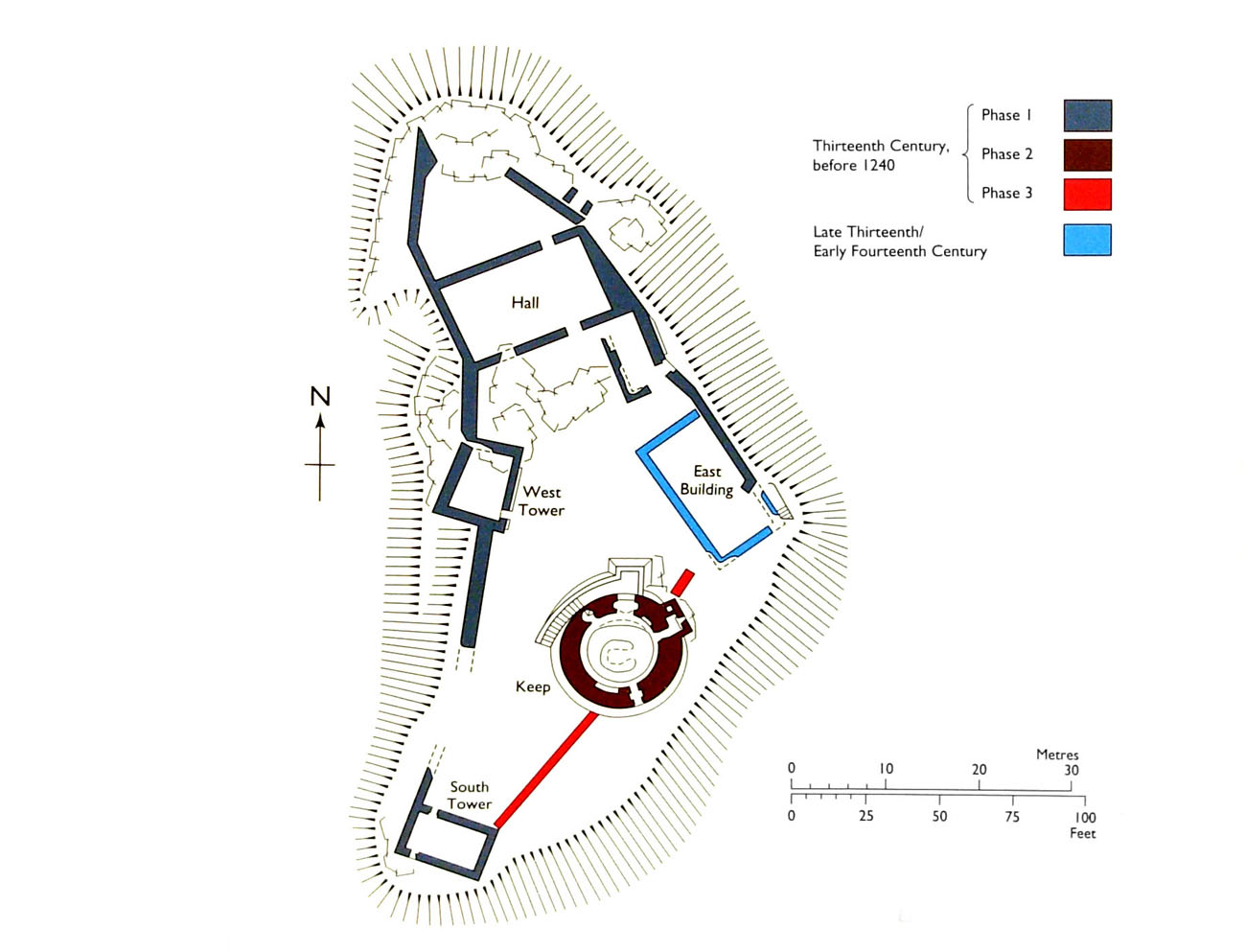

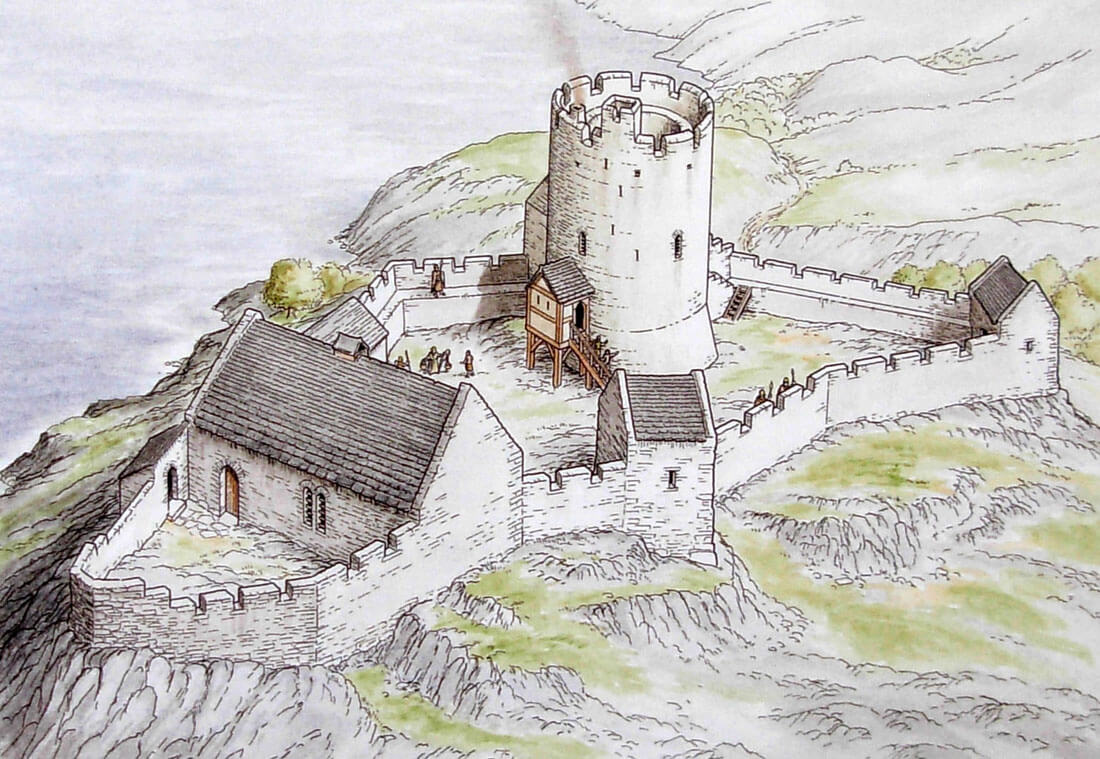

Dolbadarn was built on a hill overlooking the isthmus between two lakes: closer Llyn Peris to the north-east, and Llyn Padarn, a little further to the north-west. It had an irregular plan, similar to a triangle (about 45 x 20 meters), adjusted to the shape of the hill terrain. The defensive walls of the castle, about 5 meters high and 1.5 meters thick, run along the slopes of the hill, except for the south-eastern side. It were erected from local slate, joined without the use of mortar, except for a cylindrical, massive keep.

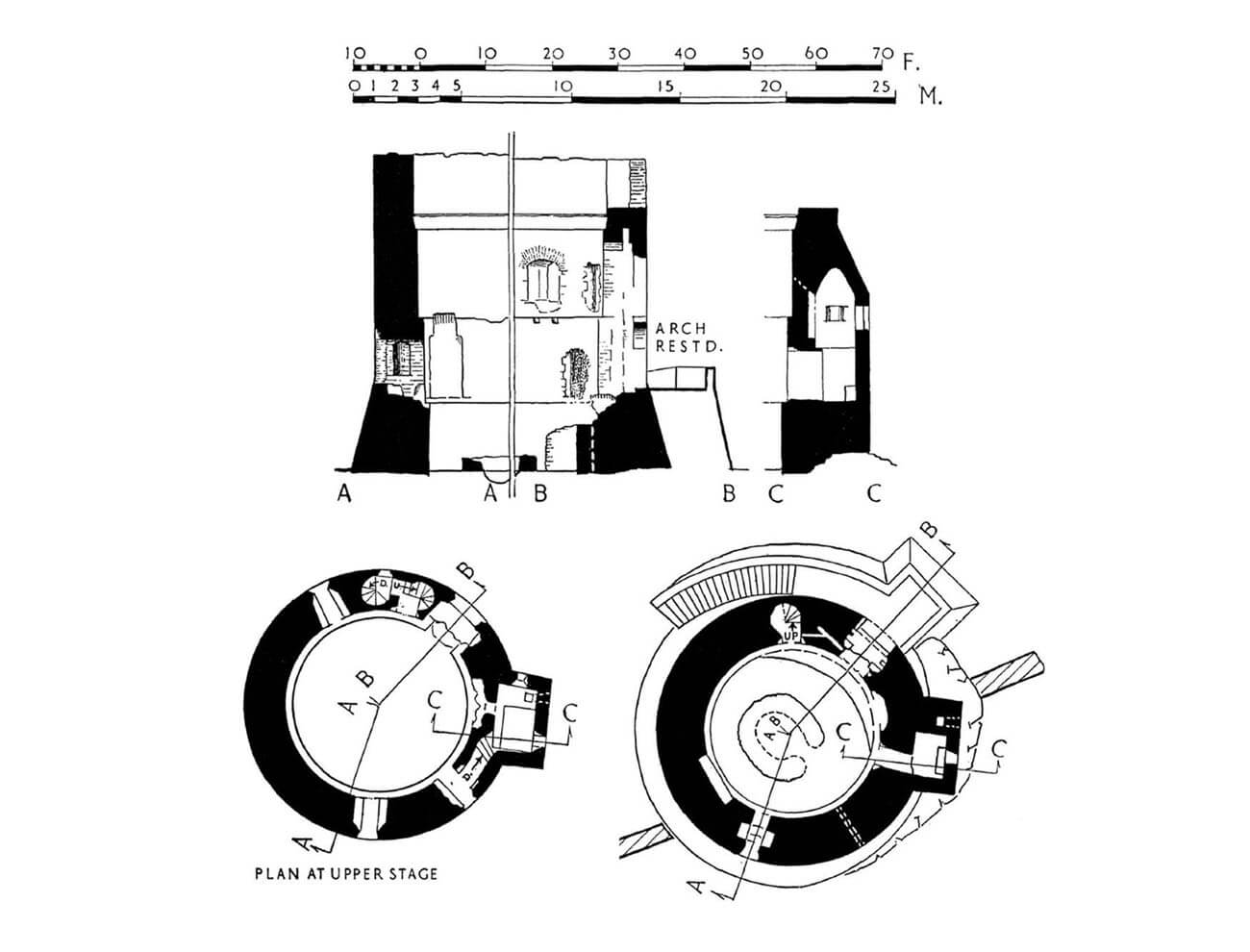

The cylindrical tower 12 meters in diameter was the main element of the castle, modeled on similar buildings from Bronllys, Longtown, Pembroke, Skenfrith, or Tretower. Its height was just over 14-15 meters to the level of the parapet. The original entrance was on the north side at the height of the first floor (about 3.6 meters above the ground), where it was accessible via wooden, easy to disassemble stairs. They were protected by a door closed with a bar and a portcullis, an unusual and characteristic feature of the Dolbadarn keep. The tower was crowned with the aforementioned paraptet and battlement, protecting the surrounding gallery for the guards.

The lowest storey of the keep, housing a dark and stuffy room, was probably used as a warehouse and pantry. It had only a single, diagonal vent, but the purpose of the crescent-shaped structure in the center has not yet been clarified. The first floor, although heated by a fireplace, also could not be used as a living room for the owner of the castle, due to the lack of sunlight (not a single larger window was pierced on this floor). Probably there were guards or the ruler’s closest servants in it. The main representative and residential storey was the second floor. There was a chamber equipped with four windows, a fireplace and a latrine in the avant-corps, accessible through a passage in the thickness of the wall. It served both the first and the second floor, discharging sewage through two chutes towards the eastern slopes of the hill. On the second floor, only the north window did not have side, stone benches, as the portcullis was pulled up there. The communication between the wooden ceilings was provided by a spiral staircase in the wall thickness, only a hatch and a ladder led to the ground level.

A timber building on a stone foundation adjacent to the western part of the keep (only two holes in the wall remained of it) probably serving as a kitchen. This location would give the opportunity to quickly deliver meals to the castle owners, and, due to the distance from other buildings, relative protection against the threatening of kitchen fires.

West of the keep, in the line of the defensive wall, a four-sided, irregular tower was placed. Similar one, but only of the shape of a symmetrical rectangle, was erected in the southern corner. It could protect the access road to the castle, and it also had a small postern gate in the south wall, leading to a ledge, carved below in the rock. In the northern part of the castle there was a rectangular hall building (15×8 meters), connected by the shorter sides with the eastern and western curtain walls. It was a representative place where feasts and celebrations were organized and guests were welcomed. The door to its interior was on each of the long sides. At the north-eastern corner near one of the entrances to the building, a latrine was placed on the outside of the defensive wall. Also on the opposite south side of the hall was a smaller, rectangular building attached to the wall. Perhaps it had auxiliary and economic functions in relation to the hall. The eastern part of the castle was occupied by another rectangular building, probably built already in English times, at the end of the 13th century. The original main entrance to the courtyard could be on the south-west side of the castle (at the defensive wall which has not been preserved until today), or possibly in the eastern part of the castle, in the wall next to the building adjacent to the hall from the south. In this case, this building would serve as a gatehouse rather than an economic building.

Current state

Nowadays, the only preserved element of the castle is a cylindrical tower – a keep. This is a valuable example of a Welsh, native building, modeled on Norman constructions. Only the outlines of foundations have survived from the remaining fragments of the castle. Dolbadarn is now owned by the Cadw government agency and is protected as a 1st class monument. It is available for sightseeing, including the possibility of entering to the keep.

bibliography:

Avent R., Dolwyddelan Castle, Dolbadarn Castle, Castell y Bere, Cardiff 2004.

Davis P.R., Castles of the Welsh Princes, Talybont 2011.

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Smith S.G., Dolbadarn Castle, Caernarfonshire: A Thirteenth-Century Royal Landscape, “Archaeology in Wales”, vol 53, 2014.