History

Construction of the castle at Denbigh began in 1282, after the occupation of North Wales by the English king Edward I. The stronghold probably stood on the site of an earlier Welsh building, called in the sources Dinbych. It was created little earlier, in 1277, on the initiative of Dafydd ap Gruffudd, brother of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the last prince of independent part of Wales. Dafydd initially sided with the English against his brother who deprived him of his lands, but in 1282 he rebelled against Edward I, starting the Second War of Welsh Independence. After the capture of Dinbych, the king established the seat of new lordship in the renamed Denbigh and granted these lands to Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. The one with the help of James of Saint George, the main architect and master of the masonry of king Edward, began building a new castle.

The construction work on the castle was not completed before 1294, when the Welsh rebellion led by Madog ap Llywelyn broke out. The castle was occupied by the Welsh forces and recaptured only towards the end of the year. The construction was resumed, although the work was prolonged, probably due to the death of Henry’s eldest son in the castle accident. Henry de Lacy died in 1311 without leaving a male descendant, which meant that the property passed on to his daughter Alice, and then through marriage to Thomas, Earl of Lancaster. The new lord of the castle was executed in 1322 for treason by Edward II, in revenge for his participation in the fall of the king’s favorite, Piers Gaveston. Denbigh was taken over by the Crown and awarded to the new favorite of the king, Hugh Despenser. Edward’s regime was overthrown in 1326 by Roger Mortimer and queen Isabel. Mortimer took control of Denbigh, although he was also overthrown in 1330 by Edward III. From then on, the castle was in the possession of William Montagu, Earl of Salisbury, who was one of the key supporters of the new king. During this period, further works on the extension of the castle and town walls continued. In the end, however, Edward III reconciled with the Mortimer family, and Denbigh was restored to them in 1355.

In the year 1400, Owain Glyndŵr’s rebellion against English rule broke out. As Edmund Mortimer was only eight years old, king Henry IV appointed Henry Percy Hotspur as commander of Denbigh. Despite the isolation, the town and the castle remained in royal hands for the next two and a half years. In 1403 Hotspur began to conspire with the Glyndŵr, so it was a strong blow to Welsh rebels when he was defeated and killed in the Battle of Shrewsbury the same year. There is no information about the castle in the later years of the uprising, but most likely it was not captured and remained in the hands of the Mortimers. The rebellion was suppressed in 1407 and Edmund continued to maintain Denbigh until childless death in 1425, when ownership changed to Richard, Duke of York.

During the Wars of the Roses, the Mortimer family supported the York case. Therefore, in 1457 king Henry VI Lancaster appointed his half-brother Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke as governor of Denbigh. The Mortimers refused to give away the castle, but after losing the Battle of Ludlow, they had to withdraw from Denbigh in 1460. A year later, the wheel of fortune turned and after the Battle of Towton, Jasper had to leave the castle. He tried again to take over the stronghold in 1468, but he failed to do so, instead the town was burnt. From that moment it was mostly abandoned by residents who moved outside the perimeter of the walls at the foot of the hill. The former, largely depopulated town began to serve as a vast outer bailey of the castle.

During the Tudor times the castle was largely neglected, the new dynasty reluctantly spent money on the fortification of dubious importance. It was not completely abandoned only because in 1536 Denbigh was made the shire center, and thus the castle had a court, prison and judges’ lodging. To save funds, Elizabeth I rented the castle to her favorite Robert Dudley, later Earl of Leicester. He made minor repairs to the castle and built a new church in the town.

At the beginning of the English Civil War in 1642, the castle was ruined. Royalist colonel William Salesbury, however, decided to strengthen it and garrisoned in it at his own expense 500 soldiers. In 1645, after the defeat of king Charles in the battles of Naseby and Rowton Heath, he retreated briefly to the Denbigh. In April 1646, castle was besieged by a Parliamentary army under the command of Sir Thomas Mytton. Colonel Salesbury withstood 6 months of siege and surrendered to honorable conditions only in October 1646. After conquering the castle, the Parliament installed a small garrison under the command of Colonel George Twistleton, the new governor. The stronghold was then used as a gaol for political prisoners, including David Pennant, the sheriff from Flintshire. In 1648, a failed royalists break-in attempt was made to save the prisoners.

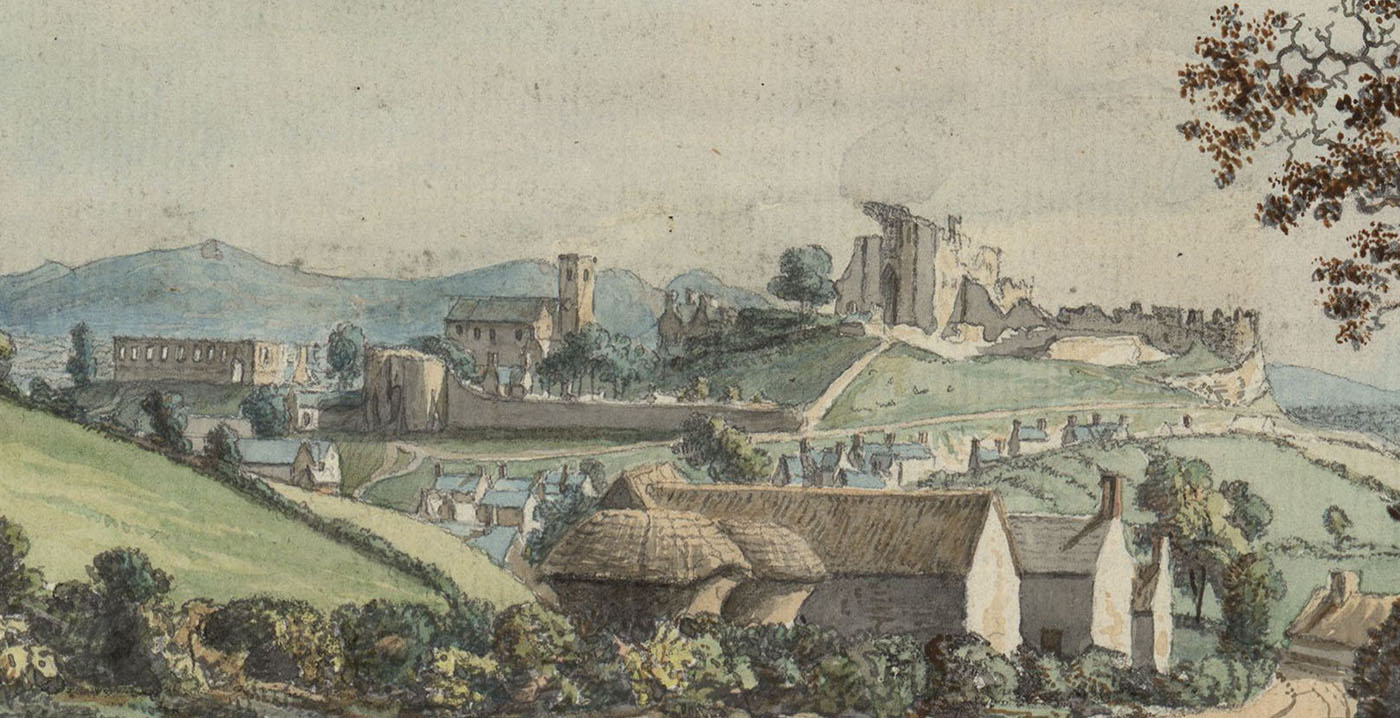

In 1659, Sir George Booth initiated the uprising of the Royalists and Presbyterians against the government. A group of royalist soldiers captured Denbigh Castle and took the garrison to captivity. A few weeks after the defeat of Booth in the Battle of Winnington Bridge, the rebels surrendered and the government regained the castle. General George Monck then ordered that it should be slighted and could not serve military purposes. Over the next century, the castle fell into a more and more ruin, stripped to obtain a free building materials. The first security and repair works were taken at the end of the 19th century.

Architecture

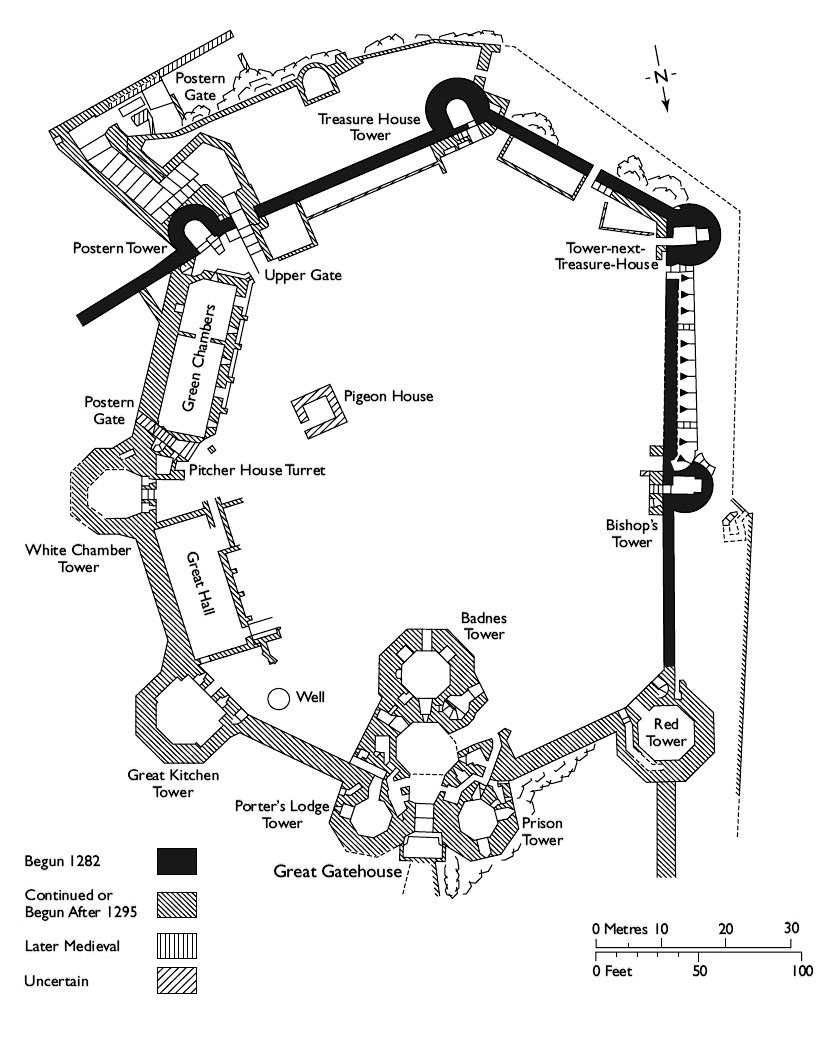

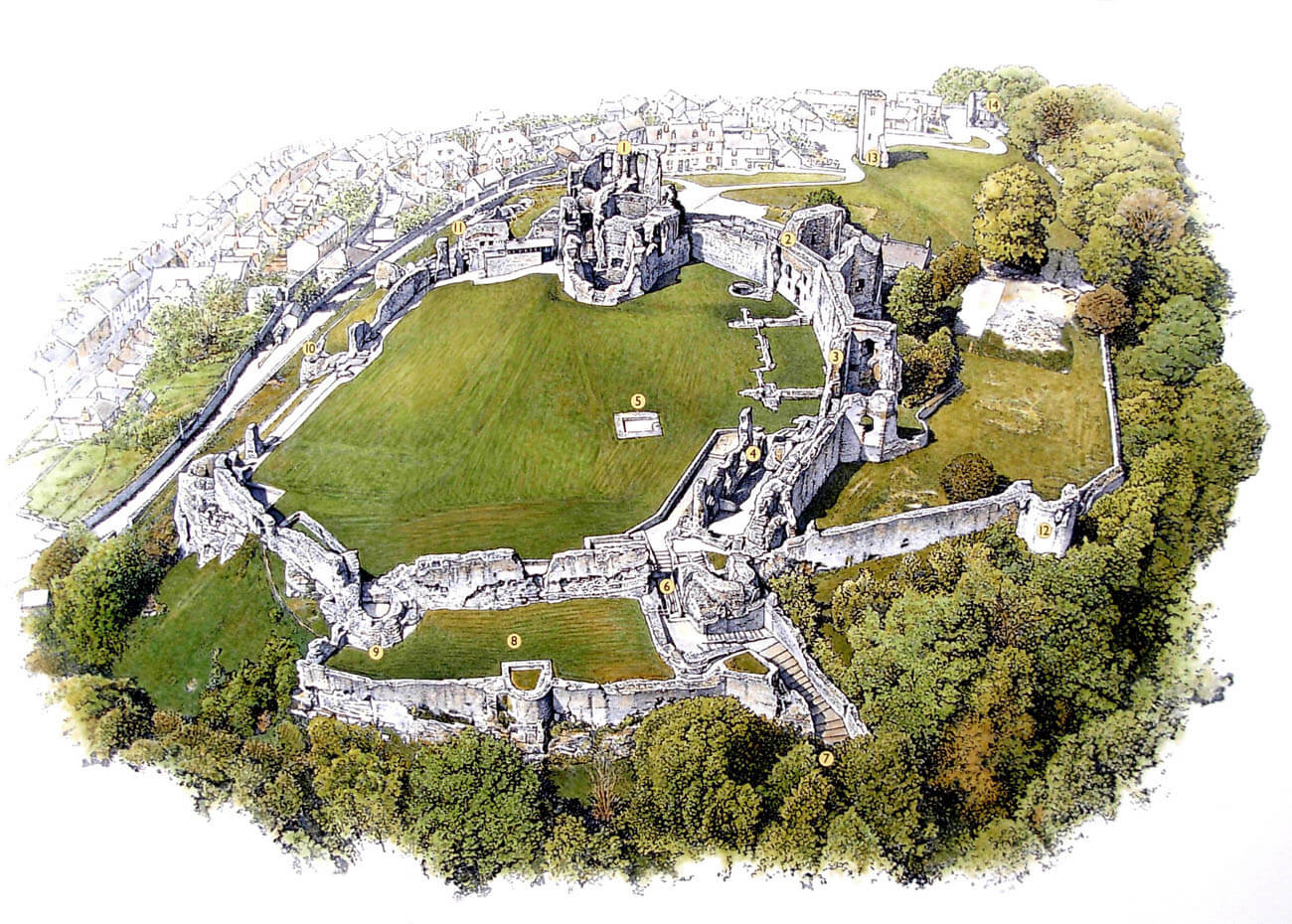

The castle was founded on a natural, easy to defend hill with rocky slope above the Clywd Valley. It was connected with the town defensive walls, which constituted the southern corner. It was built on a polygonal plan, elongated north-south, forming an internal courtyard measuring approximately 107 by 79 meters. The whole perimeter consisted of a single defensive wall crowned with a defensive wall-walk and covered with a battlement, and reinforced with numerous towers. The fortifications on the west and south sides, erected earlier, in the initial phase of the town’s fortifications had simple, short curtains of walls about 1.6 meters thick, connected by semicircular towers 9.8 meters in diameter, while the later, thicker (about 4 meters wide) walls on the east and north were distinguished by more elaborate polygonal towers. For this reason, a second, lower, outer wall was erected on the most vulnerable southern and western sides, which were not sheltered by town fortifications. The zwinger (mantlet) that separated between the two fortifications had the form of a defensive terrace, which prevented the undermining of the towers and the thinnest sections of the main defensive wall. In addition, it was divided by transverse walls to separate any attackers and prevent them from providing help.

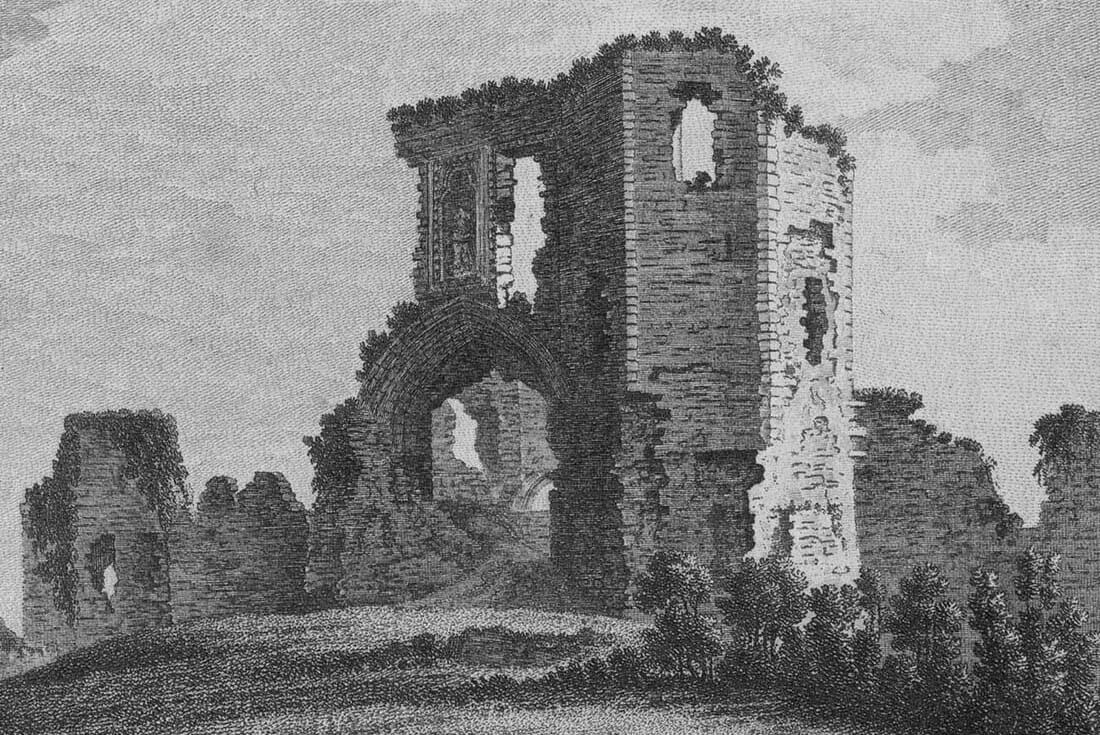

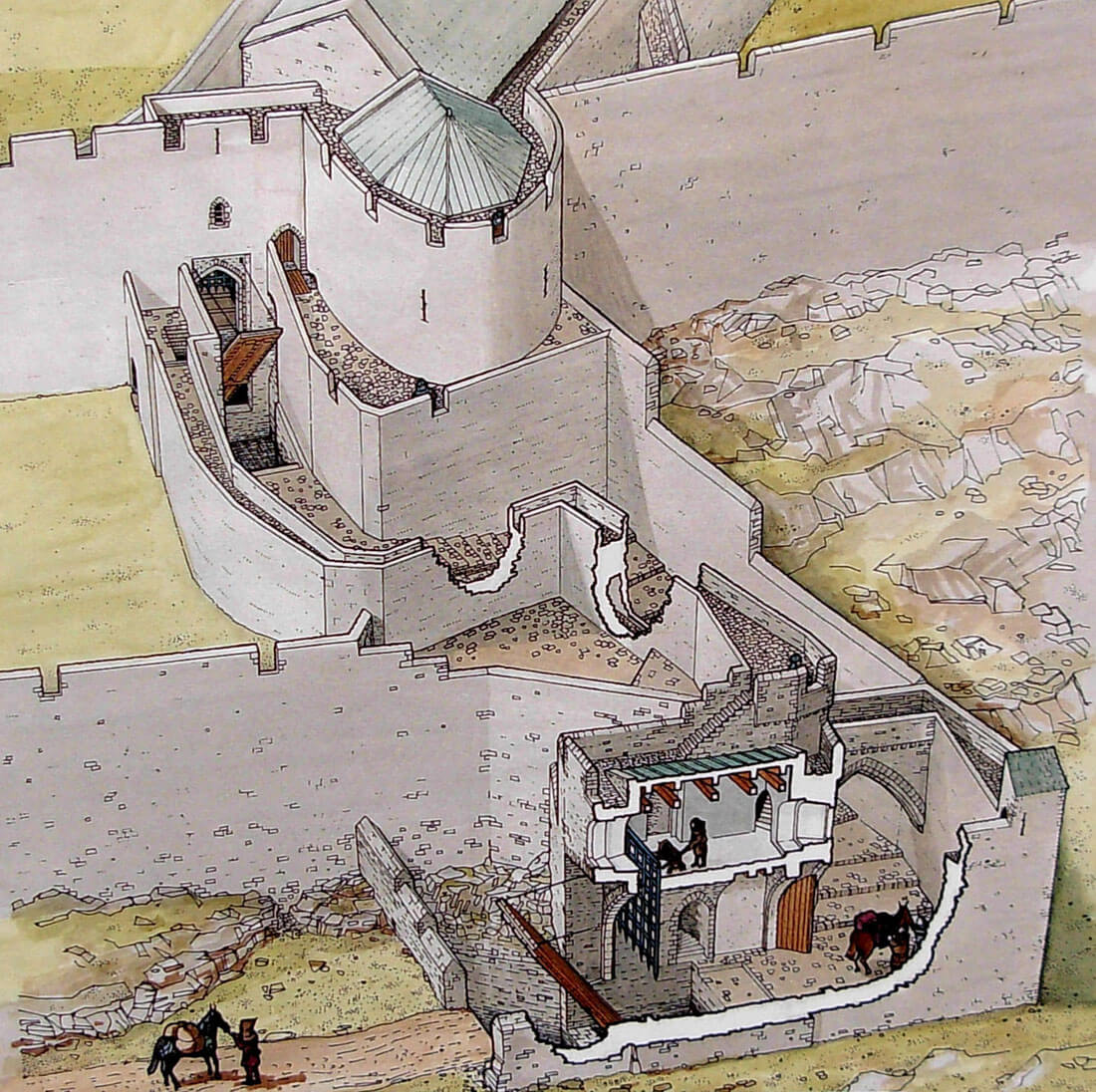

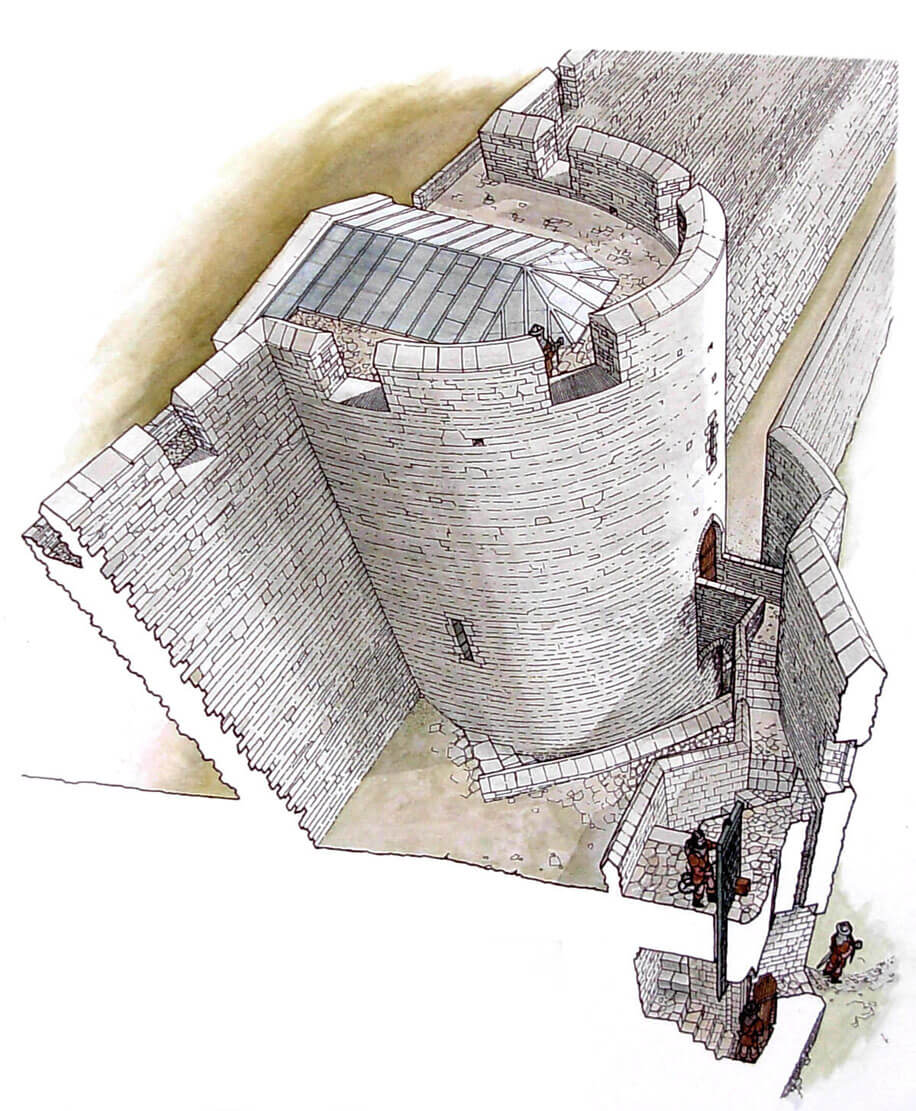

The main element of the castle was a powerful gate complex called the Great Gate, located at the highest point of the hill, on the north side. It consisted of an unusual arrangement of three polygonal towers arranged in the form of a triangle, between which a passage was made, preceded by a short foregate from the town side. The gate was built with decorative wall stripes in various colors, which were probably supposed to symbolize the royal authority of Edward I. A statue, probably of Edward II, was erected above the main entrance. The whole was defended by a ditch, 9.1 meters wide, a drawbridge located in the foregate, arrowslits directed outside and placed inside the gate passage, including two located in the ceiling, openable to the outside doors and two portcullises. After passing these protections, a central hall was reached, surrounded by three towers (the two outer ones were about 12 meters in diameter). It had a stone rib vault, above which was a warehouse and another, higher room. From the central hall obliquely directed passage to the inner courtyard was secured by a third portcullis and the door closed outside by a wooden bar. The mechanism that operated the portcullises was in the rooms on the first floor, which also served as a link between the towers. The north-west tower was called the Prison Tower. A long, diagonal corridor led to it from the entrance at the courtyard. At the ground floor level, it had two small chambers with arrowslits, the main octagonal room and to the left of the entrance a latrine with five separate chutes. Below the main room was a deep vaulted dungeon that had only a single vent and access through the upper hatch. Other gate towers had a similar arrangement. The Badnes Tower, which name came from the name of the constable, had a basement and three floors, while the ground floor equipped with a latrine and fireplace served residential function. The third tower (Porter’s Lodge Tower) had not a basement. The tower floors were accessible by means of a spiral stone staircase in the southwestern part of the gate complex, reachable from the castle courtyard and closed with two doors. The system of connections and passages provided quick access to the mechanism of portcullises, internal defensive positions and the upper gallery protected by battlement at the top of the gate. The passage in the thickness of the curtain wall also provided connection to the nearest Great Kitchen Tower. The daily functioning of the castle crew was also secured – each of the towers was equipped with latrines. Lighting and ventilation were provided primarily by narrow slit openings, but there were also larger pointed windows on the floors.

To the east of the Great Gate was the Queen’s Chapel (6.4 x 4.6 meters) and a well 15 meters deep. Right next to them, on the inside face of the wall, a rectangular building of the great hall was erected (measuring 9 x 22 meters), a place for meals, feasts and the inviting of important guests. The entrance to it led through the vestibule from the courtyard side. The second porch was directed towards private chambers in the White Chamber Tower, while from the side of the Great Kitchen Tower there were pantries, separated from the main hall by partition walls.

The north-east and east section of the castle was defended by the polygonal Great Kitchen Tower of about 15 meters in diameter and the polygonal White Chamber Tower. The Great Kitchen Tower had three floors, and the main element of its equipment were two, large, almost 5 meters wide fireplaces, located at the north and south walls of the ground floor. The upper floors were accessible directly from the courtyard via stairs. From the level of the second floor, a corridor in the thickness of the wall connected the tower with the Great Gate and the White Chamber Tower. The latter also had three floors and a basement accessible by stairs from the courtyard level, illuminated by two small windows on the sides of the entrance. The upper floors, accessible through a spiral staircase in the southwest corner, could serve residential function, as they were well lit and equipped with latrines and fireplaces.

Right next to the White Chamber Tower there was a smaller Pitcher House Tower (probably used to store water during the summer months) and a rectangular Green Chambers building, so-called because of the color of its stonework. Built in the mid-fourteenth century, the building had cellars specially designed for storing meat and wine, as evidenced by stone benches and deep niches with cut drains. There were two vaulted chambers of different sizes, well-lit and accessible separately by stairs from the courtyard level. Their vaults were based on carved corbels, among others heads of maiden, lion or devil. The upper floors originally contained living quarters, equipped with a large fireplace cut out in the perimeter wall. At the floor level, they were connected by a wooden porch based on a massive buttress to the building of a great hall. A small gate was placed between the Green Chambers and the White Chambers Tower to leave castle to the town. A little further south, the contact between the town wall and the castle curtain was closed with a transverse, short wall to protect the area washed by waste from the channels coming out of the Green Chambers. Later, this triangular, fenced off space was vaulted, and the upper platform obtained in this way could have defensive functions. Access to it led through a spiral staircase in the south-east corner of the Green Chambers.

The southern side of the castle was closed by a three-storey, half-round Postern Tower, flanking the Upper Gate next to it and the town defensive wall. The exit led through a drawbridge, then along a cobbled ramp, turning in front of the Postern Tower and once again turning to the Lower Gate gatehouse, preceded by a small foregate since the late Middle Ages, flanked by a small horseshoe tower of the outer defensive wall and the larger Treasure House Tower located in the main defensive wall. Originally, due to the large slope of the terrain, the passage had a stairs for the pedestrians on the left and an inclined but even ramp on the right for horses. In addition, a walk-wall for defenders ran along the crown of the gate’s neck wall, and a thickening housing the defensive gallery was added in front of the Postern Tower. The Lower Gate was storied with the mechanism of a portcullis and a drawbridge on the upper floor. In the eastern corner there was a latrine with a chute directed outside the castle.

The Treasury House Tower had a similar appearance to Postern Tower. Access to its two upper floors was originally only possible from the sidewalks on the perimeter walls, but later to facilitate access, stairs were also added to the inner facade of the tower on the courtyard side. On the inner side of the south-west wall of the castle corner, originally there were stables, a blacksmith’s forge and warehouses.

The western fragment of the castle fortifications was reinforced by the semicircular Tower Next Treasure House, the semicircular Bishop’s Tower and the huge octagonal Red Tower from the first half of the fourteenth century, named because of the red sandstone used in its construction. It connected the wall and defensive walk-wall with the town’s fortifications, and then the town gatehouse and the northern gate of the castle. Stairs led from the courtyard to it basement, next to the staircase led to the upper two floors, and the third entrance through a long corridor in the thickness of the wall reached the wall and the town gatehouse. A non-preserved building, presumably a court or armory, was added to the wall from the courtyard side.

A side wicket (sally port) operated at the Bishop’s Tower to allow secret access outside the castle. It connected through the porch at the outer defensive wall and through the stone footbridge with the tower’s floor. The wicket itself was protected by a narrow passage with stairs ended with a portcullis and a door placed at an sharp angle. Each of the two short sections of the passage could have been fired from the upper murder holes.

Current state

The castle has survived in the form of a legible ruin. Its most characteristic element is the northern gate complex, that is the magnificent Great Gate, the most developed gatehouse of the Anglo-Norman architecture of Edward I. Also the Great Kitchen Tower, the White Chamber Tower and the Treasure House Tower, along with a defensive wall on a large part of the perimeter have partly preserved. The relics of the Green Chamber’s building stand out in the inner ward. The castle is under the care of the governmental Cadw agenda, which makes it available to visitors.

bibliography:

Butler L., Denbigh Castle, Cardiff 2007.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.