History

The construction of the castle began in 1295 on the initiative of Roger Mortimer de Chirk, within the chain of strongholds of king Edward I in the north Wales. As the king had insufficient resources to maintain a large number of castles and garrisons in the face of constant struggles with the Welshmen, he tried to share the financial burden with his wealthy magnates, establishing a number of lords in Chirk, Denbigh, Hawarden, Holt and Ruthin. In each of these sites, the recipient was responsible for building a castle that would protect the surrounding area. The Chirk castle protected the entrance to the Ceiriog Valley and was the administrative center for the Chirkland march. The construction of the stronghold lasted until 1310, but it was never completed.

Roger Mortimer was appointed by the king as Justice of Wales, becoming an important figure at the court, but In 1322 he supported rebellion of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, against Edward II’s hated favorite, Hugh Despenser. When the revolt failed, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and his property was confiscated. Roger died in prison in 1326, but in the same year his nephew, Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, fled to France, where he joined queen Isabella, the unwelcome wife of Edward II. After their return to the country and the successful overthrow of the king, Mortimer regained his castle, but enjoyed it only until 1330, when he himself was sentenced to death by the new ruler, young Edward III. Chirk returned to the English Crown again. The local lands were devastated, as Mortimer was not very popular in Wales, and on news of his fall, the Chirkland tenants plundered his lands.

In 1334 king Edward III granted Chirk to Richard FitzAlan, Earl of Arundel, nicknamed Copped Hat. He was one of the richest people in the kingdom, but his family rarely stayed in Chirk, making the castle still unfinished. His son, also named Richard, fourth Earl of Arundel, was one of the Lords of the Appeal, the magnats, who rebelled against Richard II in 1388 and forced the king to rule under supervision. When Richard II regained control, in 1397 he lost Richard FitzAlan. Chirk was again confiscated by the Crown, until the son of Richard, Thomas FitzAlan, the fifth Earl of Arundel, joined forces with Henry Bolingbroke, who in 1399 overthrew the king and as king Henry IV, he returned FitzAlan property. At the beginning of the 15th century, Thomas FitzAlan rebuilt the castle, probably in the face of the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr, which began in 1400. Because he died of dysentery during the siege of Harfleur in 1415 without a male heir, Chirk returned to the Crown.

In the fifteenth century, the castle often changed owners, who did not invest in the development of the building. In 1439, Chirk was purchased by the powerful and influential Cardinal Henry Beaufort, and in 1447 it was given to his nephew, Duke of Somerset, one of the Lancaster leaders during the War of the Roses. When his son Henry was sentenced to death in 1464, Chirk was assigned to Richard, Duke of Gloucester, later King Richard III, who, however, in 1475 exchanged the local goods for a Yorkshire estates with Sir William Stanley. William was to carry out the necessary repairs at the castle. Although he initially maintained good relations with the new Tudor dynasty, in 1495 he was executed on suspicion of conspiracy with the Yorks.

In the first half of the 16th century, the Tudors handed over the castle to the royal officials in exchange for loyal service. One of them in 1529 rebuilt the southern wing of the castle. In 1563, Queen Elizabeth gave Chirk to her favorite Robert Dudley. In his time, an survey was made in the castle indicating that the building was dilapidated, partially ruined, with rotten wooden elements. The situation improved only in 1593, when the Chirk was sold to Thomas Myddelton, a merchant and founder of the East India Company. It then became his residence and an administrative center for Welsh interests. Therefore, he transformed the castle into an impressive manor house with a new northern range with elegant dining rooms, living rooms and a kitchen. The son of Thomas Myddelton, also named Thomas, was a supporter of the Parliament during the English Civil War, but during the “Cheshire Uprising” of 1659 he changed sides in favor of the exiled Charles II. This resulted in the siege of the castle, during which the eastern fragment and two towers were destroyed (although the direct reason for the surrender was to be the lack of water). In 1660 Charles II was restored to the throne, and Chirk returned to Thomas Myddelton, who died three years later. The renovation work at the castle, which was carried out in 1664-1678, included the reconstruction of the eastern part of the building, and the reconstruction of two towers on medieval foundations. The Myddeltons lived in Chirk until the beginning of the 20th century, when Thomas Scott-Ellis managed the area again. The castle was taken under state protection in 1978.

Architecture

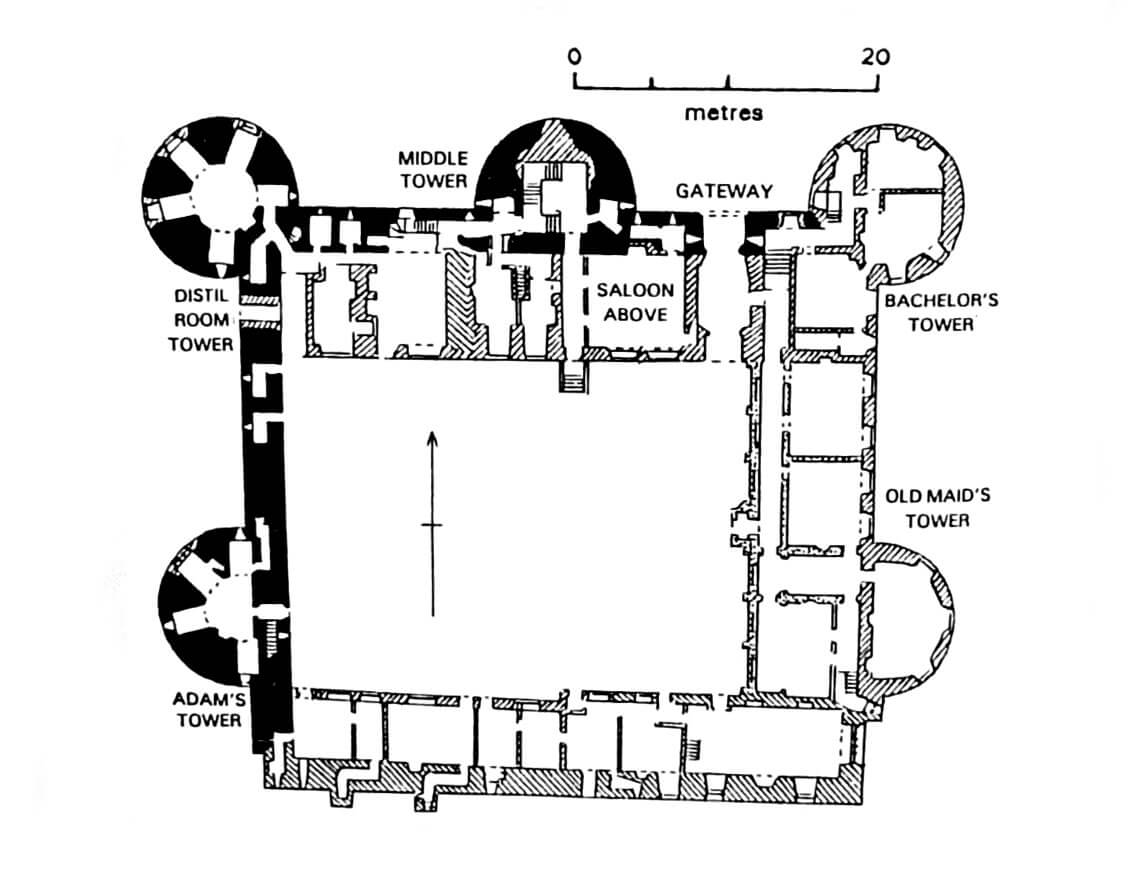

The castle was situated on the top of a hill, which in the south fell steep slopes towards the Ceiriog River. It was probably planned to erect as a large, concentric stronghold on a regular quadrilateral plan, consisting of two perimeters of defensive walls reinforced with towers. This assumption is probable because Roger Mortimer was accompanying in his works by the architect of king Edward I, James of Saint George, which contributed to the construction of such castles as Harlech, Beaumaris, Conwy or Caernarfon. However, like Beaumaris Castle, Chirk was never completed. The outer fortifications were not started, and of the seven to nine semicircular and cylindrical towers of the inner circumference, only five were erected.

The straight curtains of the walls connecting the individual towers were very thick. They were about 4 meters wide, thanks to which a series of chambers, passages and stairs could be created inside them. The fortifications finally marked a square courtyard with the sides of about 38 meters, although it was originally planned to be about 52 meters long on the north-south line. Until the beginning of the 15th century, the castle did not have a stone closure on the south side (as the safest one left at the very end of construction). Erected around 1400 by Thomas FitzAlan, the southern wing no longer had any towers or major defensive features.

The corner towers had a cylindrical form with a diameter of about 11 meters, and those placed in the center of the curtains were semicircular. Their original height remains unknown, perhaps they never exceeded the height of the wall curtains (presumably they had four floors). However, they were strongly protruding in front of its face, providing the possibility of flanking fire, including securing the gate passage, which was placed in the eastern part of the northern curtain of the wall. It was closed with a portcullis, lowered in guides embedded in a very high arcade with a slightly pointed top, creating a niche inside which there was a gate portal.

Initially, the residential functions in the castle had mainly the rooms inside the towers and narrow chambers located inside the western curtain, about 5 meters thick. In the late-medieval southern wing, in the eastern corner, a chapel was arranged, illuminated by a pair of tow-light windows and a large five-light window on the eastern side. To the west of it, there were living quarters with latrines and a representative room (hall) on two floors. They were significantly remodeled in the first half of the 16th century.

Current state

The castle has survived to modern times in a much rebuilt form. The medieval origins has the western and partly northern part of the monument with three towers (west, north-west and central north one), and the south wing, which is one hundred years later, with interiors modernized in the early modern period. The eastern part of the castle was rebuilt in the 17th century on medieval foundations, but it has much thinner walls and a different interior layout. Probably all the towers were also lowered by one level, and the original appearance of the stronghold spoil the modern windows in all the towers and walls. From the medieval elements one can see a gate with a high arcade for a portcullis and several Gothic portals and small windows facing the inner ward. Among the interiors of the towers, the least transformed rooms today have the western tower (known as the Adam’s Tower), probably originally the seat of the castle constable.

The castle is open to tourists from March to October, with limited opening dates in November and December. In its vicinity, you can also see the Offa’s Dyke, the earth fortifications of the king of Mercia from the second half of the 8th century, erected against Welsh neighbors. Its remains run parallel to the access road to the castle.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.

Stubbs S., Chirk Castle, Swindon 2009.

Taylor A. J., The Welsh castles of Edward I, London 1986.