History

The medieval castle in Cardiff was erected on the site of a Roman fort from the first century BC who guarded the then border, during the conquest of the Celtic tribe of the Silures. As the Roman border moved west, the fortifications lost their importance and were replaced by two smaller, following each other, wood and earth forts in the northern part of the first fort. In the middle of the 3rd century, in the face of the threat of Irish pirate invasions, the Romans erected another, fourth fort, with already brick fortifications, the remains of which were later incorporated into the castle. The fort was probably garrisoned at least until the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 5th century, but it is not known when it was finally abandoned.

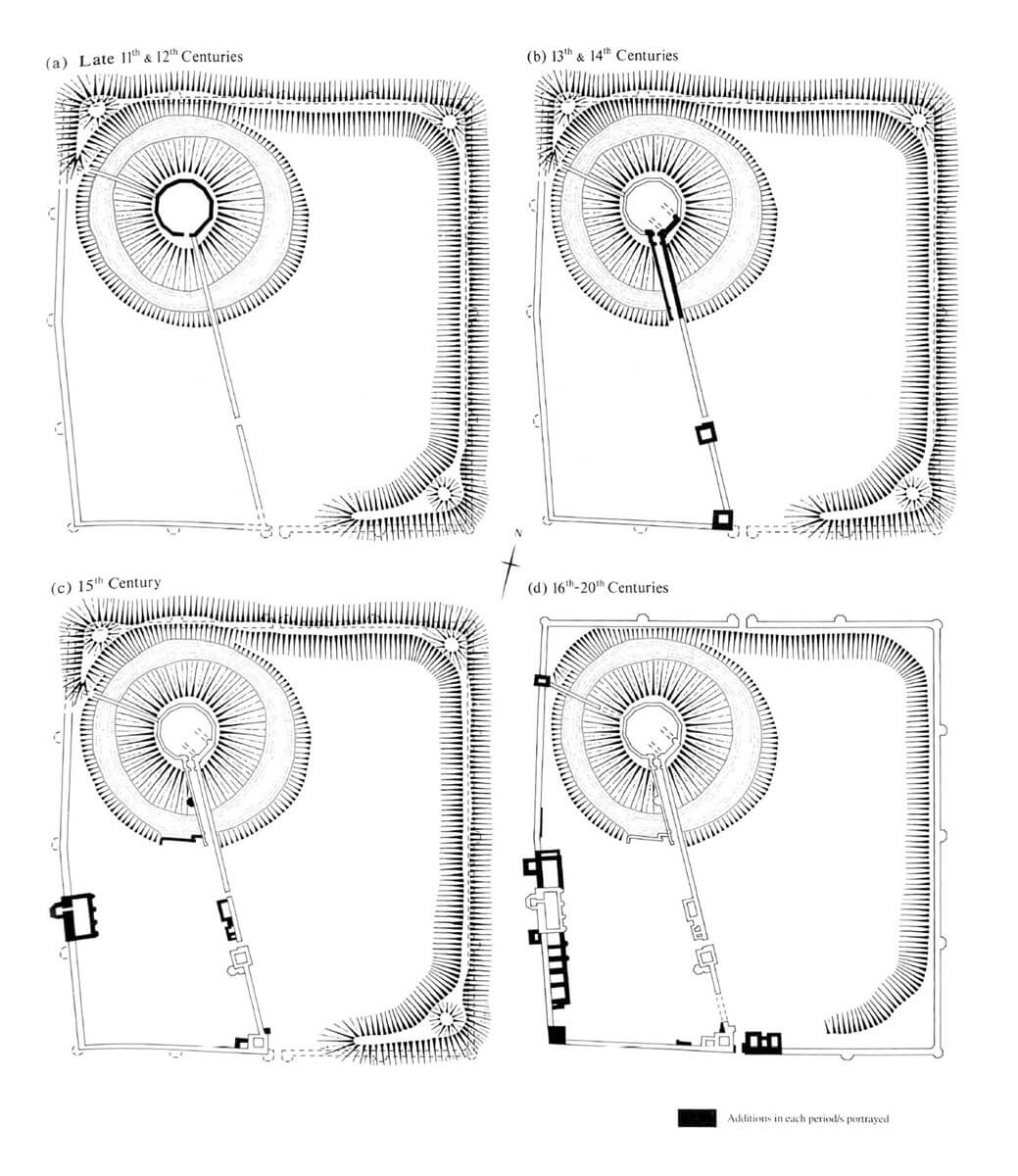

From the late 60s of the 11th century, the Norman conquest of southern Wales began. The progress of the invaders was marked by the construction of castles, often in the areas of ancient Roman buildings. Their re-use meant significant savings of time, money, and especially building materials. The Norman castle in Cardiff was erected by king William the Conqueror in 1081 on his return from St Davids, or by Robert Fitz Hamon, Earl of Gloucester and follower of the king in 1091, after defeating Iestyn ap Gwrgan, the last independent ruler of Glamorgan. A royal foundation would be indicated by the mint already operating in Cardiff in the 80s of the 11th century, though castle was first recorded in written sources during Fitz Hamon’s tenure in 1093-1107, when he donated to Tewkesbury Abbey with the “capellum de castello de Cairdif”. During this period, the castle was the main center of Robert’s reign over the Glamorgan region. Cardiff was then located near the sea, which solved the supply problem, was also well protected by the rivers Taff and Rhymney, and controlled the old Roman road running along the coast. In 1102, a borough was established near the castle, secured with wood and earth fortifications in 1184.

Robert Fitz Hamon was killed as a result of after battle injuries in 1107, and his daughter and heiress, Mabel, married Robert Fitzroy, the illegitimate son of English king Henry I. The king gave Robert the earldom of Gloucester and made him Lord of Glamorgan. The new ruler of the castle at the request of king Henry, imprisoned in his fortress the second prince of Normandy and the elder brother of the king, also Robert, who stayed in the castle against his will from 1126 to the death in 1134. Around 1140, Robert, Earl of Gloucester rebuilt the central part of the castle from timber to stone, probably because of the Welsh revolts a few years earlier, after the death of King Henry I.

Robert died in 1147 and was succeeded by his son William. In 1158, he was abducted from Cardiff with his wife and son after a surprising night attack on the castle by the Ifor Bach, Lord Senghenydd. Eventually they were freed when demands were conceded, but when William died in 1183, he had no male heir. The castle then passed to King Henry II, and soon to Prince and later King John, through his engagement with William’s daughter, Isabel. The stronghold was not captured during the rebellion of Morgan ap Caradog of Afan, but the town was burned down. Reinforcements were sent from Bristol, the town was soon fortified, and in the years 1187-1188 the castle was repaired at the expense of the Crown.

In 1202, the William de Braose took custody of the castle, replaced five years later by Fawkes de Bréauté, who in 1209 was to supervise subsequent repairs in Cardiff (as well as in Neath and Newport). A year earlier, King John ordered barons and knights to renovate his houses in the castle bailey in “Kaerdif”, to which they were obliged during their service and guarding the castle. In 1217, the castle passed into the hands of Gilbert de Clare, the son of Isabel’s sister. It was from now an important family seat in South Wales, although de Clares preferred to live in their castles in Clare and Tonbridge. Gilbert’s son, Richard de Clare, the sixth Earl of Gloucester, in the middle of the thirteenth century began another construction works to raise the castle’s defenses. It could have been caused by the threat of hostile Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Cardiff, however, remained not endangered during the conflict, mainly due to the construction of a strong nearby Caerphilly Castle by Gilbert II at the end of the 13th century.

Richard’s grandson, the last heir of the family, Gilbert de Clare, died at the Battle of Bannockburn. The castle had to be placed under royal custody until the property of the de Clare family was divided between the earl’s three sisters. It was held by Payn de Turberville, Lord of Coity, when the dangerous Welsh uprising of Llywelyn Bren broke out in 1316, caused by the poor harvest and severe rule of the Despensers, royal favorites. The king ordered Payn to strengthen the garrison and the defense of the castle, and soon 150 men-at-arms and 2 thousand footmen left it to help the besieged Caerphilly. In the same year, John Giffard became the new custos of the castle on behalf of the king. He carried out numerous renovation works in Cardiff, including the reroofing of the buildings and the Black Tower, the bridge to the keep and some furnace.

In 1317, the lordship of Glamorgan was awarded to Hugh Despenser, favorite of King Edward II (his wife Eleanor was the eldest sister of the last Earl Gilbert). Two years after the fall of the Welsh uprising, Llywelyn was hanged, stretched and dismembered in Cardiff Castle. Execution aroused many criticisms, both on the English and Welsh side. Looking for a scapegoat, in 1321 Hugh captured Sir William Fleminge, first arresting him in the Black Tower of Cardiff Castle and then performing the execution. Soon after, the unscrupulous and greedy rule of the Despensers provoked a conflict with the other earls of the march, during which the castle was captured and plundered. Eventually, the Despensers regained Cardiff in 1322 following the victory of the royal forces at Boroughbridge. They kept it until the end of the century, despite the execution of Hugh Despenser for treason in 1326.

In 1400, rebellion led by Owain Glyndŵr broke out in North Wales, spreading rapidly to the rest of the country. In 1404 Cardiff and the castle were captured and burned by rebels. The rage of the attack was to some extent due to the hatred still felt by the Welsh against the Despensers for the murder of Llewelyn Bren. Despite initial successes, after a few years the Glyndŵr uprising was suppressed, and by the time of surrender in 1415 all lost castles had already been recaptured. The damages to Cardiff Castle caused by the Welsh was supposed to be still visible at the end of the 15th century.

A new stage in the history of the castle, and at the same time the last period of its medieval glory, began when the heiress, Isabel Despenser, first married Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Worcester in 1411, and then, after his death, in 1423 she married Richard de Beauchamp’s cousin, Earl of Warwick. During their times, the castle was enlarged by late-Gothic residential buildings on the south-west side, putting convenience over defense. With the death of their son Henry in 1445, the male Beauchamp line died out, and the lordship of Glamrogan passed through marriage to the Neville family, involved in the War of the Roses that had started in 1455. Control over the castle frequently changed then, and since all of its owners belonged to the leading families of the kingdom, they did not live in Cardiff or invest in repairs to the castle, which gradually began to decline.

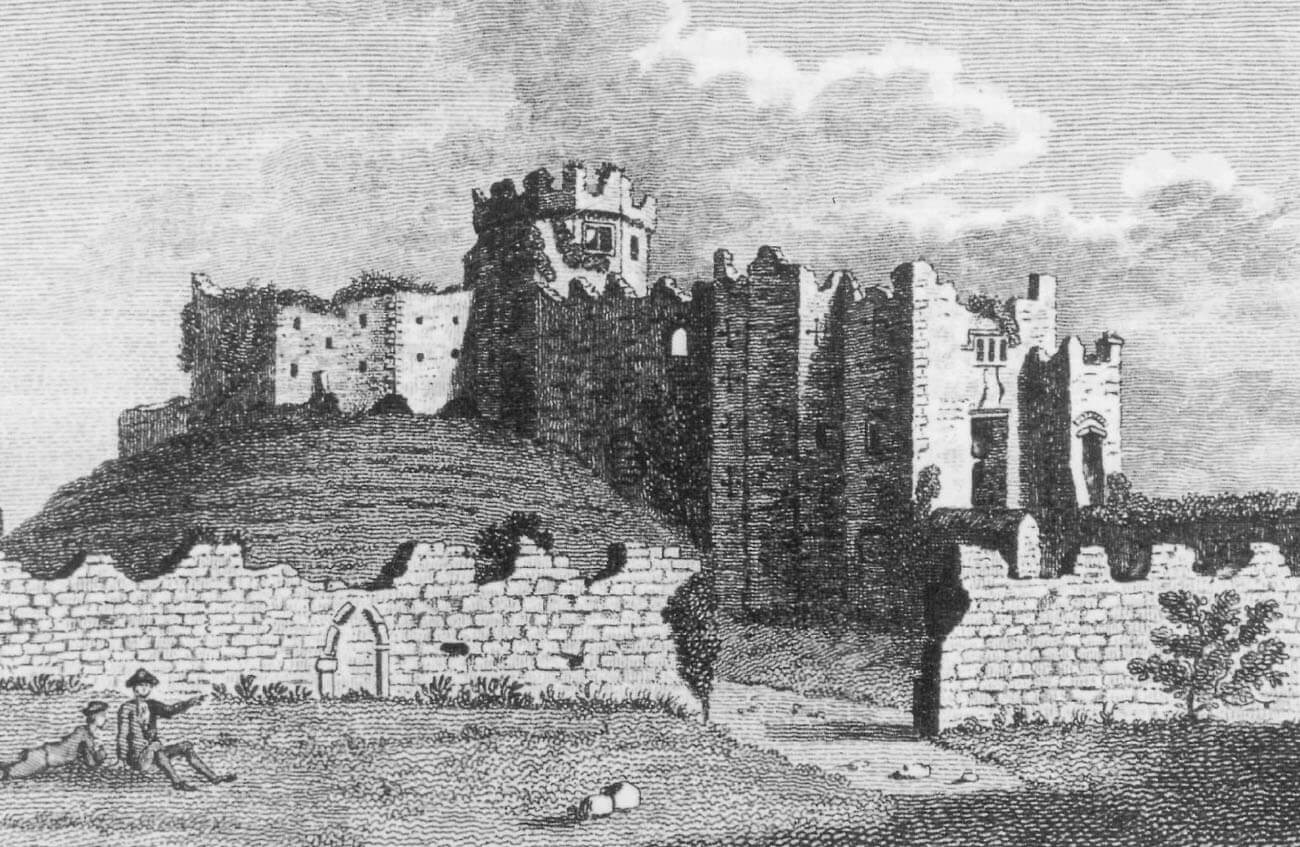

In the middle of the 16th century, the castle and lordship passed to the William Herbert, a member of one of the most powerful medieval families in England. In the time of his son Henry, in the last quarter of the 16th century, a program of great reconstruction and renovation of the castle began. However, during the English Civil War, the Herbert family sided with the Parliament, for which King Charles I confiscated Philip Herbert’s estates and handed over the castle to Sir Anthony Mansel. After the defeat at Naseby in 1645, the ruler sought refuge in Cardiff and tried to organize new forces in the area, but at the end of the year the castle was surrendered to the troops of the Parliament. During the following years of war Cardiff changed sides of the conflict, but the castle avoided major damages. Finally, in 1649 it was captured by Parliament’s army, which, unlike many other Welsh castles, did not order its destruction. After the war, Herbert was able to make the necessary repairs to the castle, but began to spend more and more time outside, and in 1776 the last heiress, Charlotte Jane, donated the property to her husband John Stuart. John Crichton-Stuart, the second Marquess of Bute, then its successor, the third Marquess of Bute and his son, made in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, thorough rebuilding of the castle, due to which it received, in large part, the character of a neo-gothic Victorian mansion.

Architecture

The castle was situated on the eastern bank of the Taff River, near its mouth in the south into the Bristol Channel. In the 11th century, its core was a motte and bailey structure with a keep placed on an earthen mound, one of the largest erected in Wales. Its height was about 10.7 meters, and its diameter was 33 meters. It was surrounded by a wooden palisade running along the slopes and a 9-meter-wide ditch at the foot. Initially the ditch was crossed over a wooden bridge.

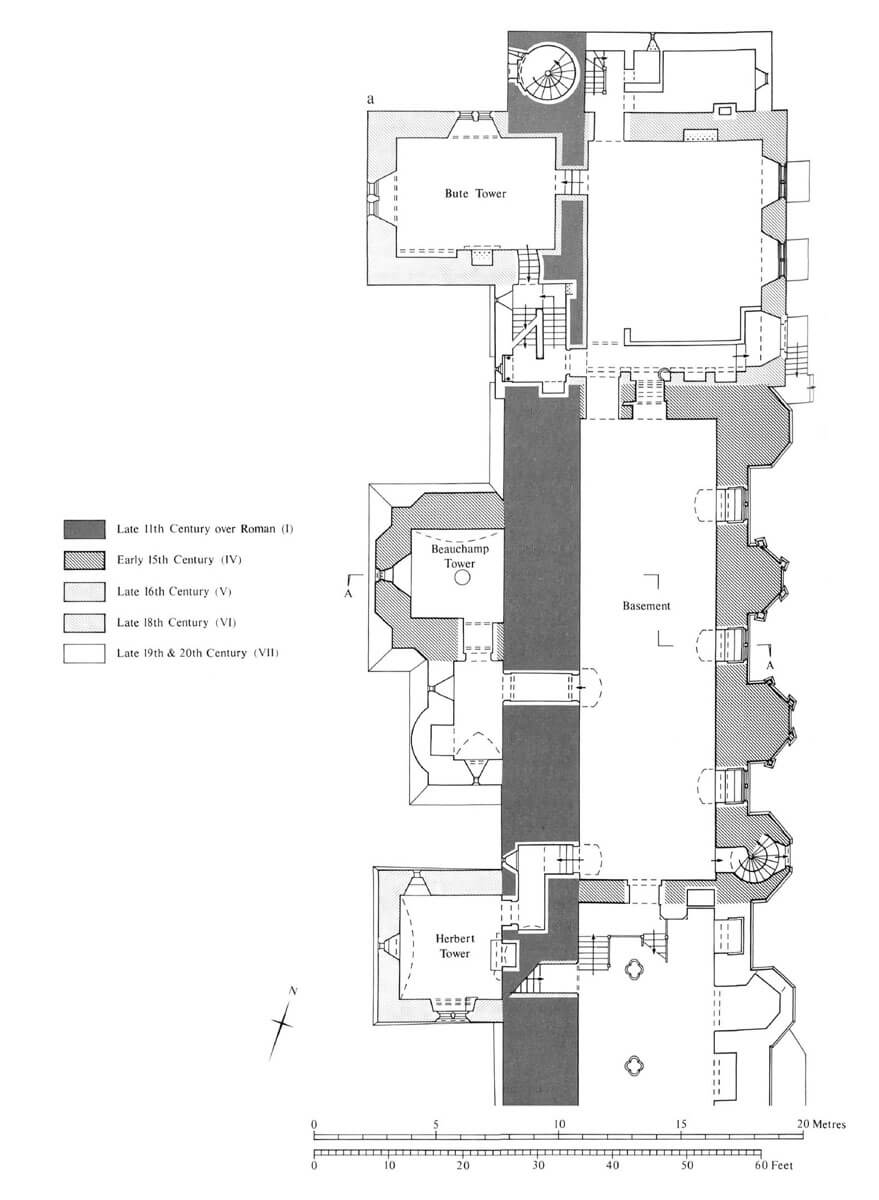

The Normans used part of the old, disrepaired Roman fortifications as the basis of the outer perimeter of the castle, thanks to which a fortification ring on a square plan was created, covering an area of 3.34 ha (about 200 x 185 meters). New defensive ditches and an earth rampart, 8 meters high and 20 – 27 meters wide at the base, were created from the north and east, while the Roman wall was renovated in the west and south (without the north-west corner). This wall was originally 3.2 meters thick at the base and 2.6 meters in the higher parts. It was built of regular blocks of limestone tied with a strong cement mortar. In Roman times it was reinforced with 18 towers, regularly placed around the perimeter, protruding in front of the curtain face, two of which flanked the northern gate and two flanked the southern gate. Medieval builders, however, did not rebuild them, they only renovated simple curtains, supplemented with unworked stones. After the reconstruction, their height was less than 8 meters, they were topped with a wall-walk formed on an offset and battlement. Inside, the castle area was additionally divided by a palisade, and since the 12th century by a transverse stone wall with a thickness of 1.8 meters. It created a smaller inner courtyard on the west side and a larger outer courtyard in the east (upper and lower wards). The transverse wall was over 6 meters high; wall-walk ran along it, it was protected on both sides by a parapet with battlements. In the south, it was connected with the perimeter wall at the site of the former Roman gate, while on the sides it was not preceded by any ditch. On the south side of the castle, a medieval settlement developed, and then a town, fortified with a stone wall in the 13th century.

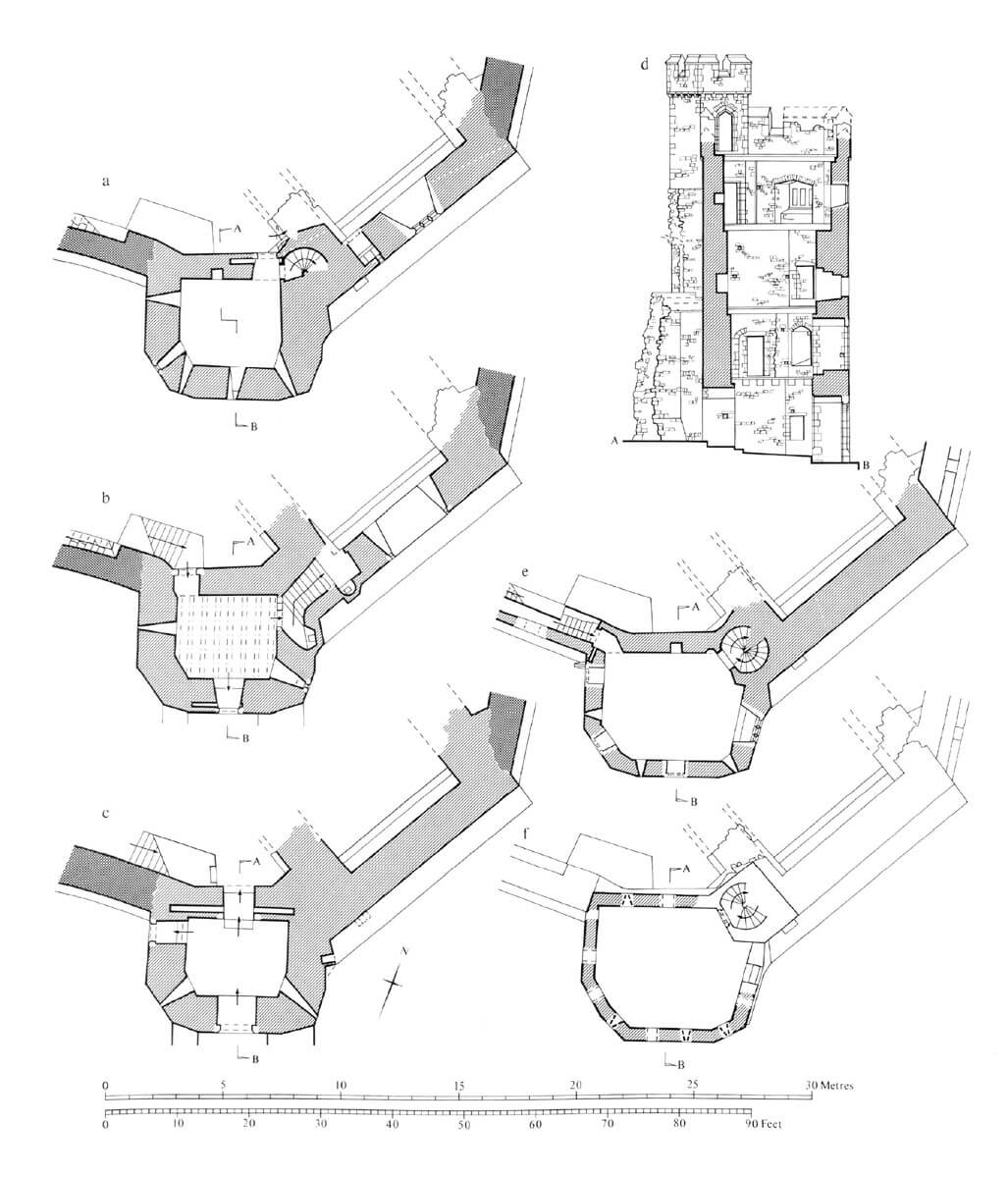

Around 1140 – 1150, the wooden keep was rebuilt. The top of the mound was then surrounded by a twelve-sided stone wall, 8.2 meters high and 1.6 meters thick above the battered plinth (shell keep), separating a courtyard with a diameter of about 23 meters. The keep wall was topped with a wall-walk, accessible from the south by narrow stairs from the courtyard level. It was protected by a battlement. The oldest buildings inside the keep were of wooden construction. They were probably attached to the wall on the south-west side, where a shallow recess 3.8 meters wide was created, narrowing in the upper parts. The next buildings were located on the north side, because there, at the height of the first floor, the wall was pierced with two windows, and stone corbels were placed on the internal facades.

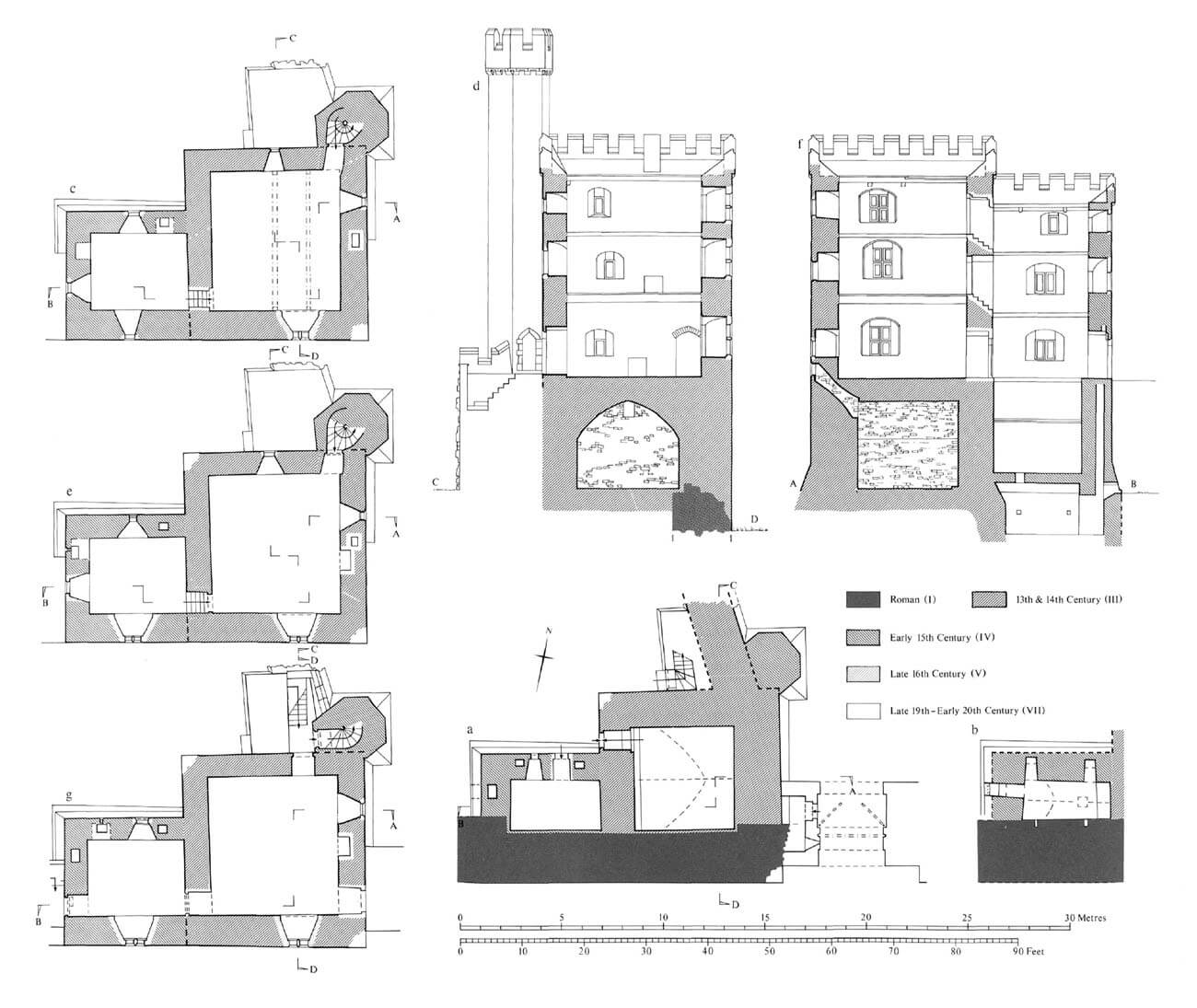

At the end of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, during the de Clare family, in the middle of the southern curtain, and at the same time in the south-eastern corner of the upper ward, the so-called The Black Tower was built, flanking the nearby entrance gate to the castle. The plan of the tower had dimensions of 9.3 x 9 meters, walls 2.2 to 2.5 meters thick (the northern and western walls were even thinner) and about 18 meters high to the level of the parapet with battlement. Its southern wall was created by the curtain of the castle’s defensive wall. Initially quadrilateral, after about a hundred years, it was extended with a rectangular annex with a basement on the west side (adjacent to the wall curtain) and a polygonal, corner stair tower on the north-east side. Inside, the tower housed a vaulted ground floor and three upper floors, originally reached by external wooden stairs, and from the 15th century by a staircase in the aforementioned corner turret. The ground floor was a dark square chamber 5 x 5 meters with a barrel vault at a height of 4.3 meters. It had no connection with the adjacent gate passage, or any window, only a narrow ventilation opening in the eastern wall. Presumably, from the moment of its building (and certainly in the 16th century), it served as a prison cell. The first floor was connected to the wall-walk in the crown of the transverse wall and by the passage and the western annex with the wall-walk on the southern wall. Due to the decreasing thickness of the walls, first floor housed a more spacious chamber with dimensions of 6.8 x 6.4 meters. It was used for living purposes, because it was heated by a fireplace and better lit. The two upper floors looked similar, but the changed height difference meant that there had to be steps between them and the western annex. The more austere third floor of the tower did not have a fireplace, as did all the rooms in the annex, which, on the other hand, were equipped with latrines embedded in the thickness of the wall. The entire Black Tower complex certainly served to provide premises to the staff (doorman, his deputy) and guards of the main entrance gate to the castle, as well as, obviously, to protect it.

In the 13th or 14th century, the northern and eastern outer wooden and earth fortifications were also rebuilt into a stone wall, but much weaker than the older curtains. After entering the lower ward through the southern gate at the Black Tower, in order to reach the upper ward, one had to get through another gate in the transverse inner wall. This gate, located more or less in the middle of the transverse wall, was flanked from the beginning of the 13th century by a four-sided tower with a polygonal communication turret in the south-west corner. The tower in the transverse wall was built in a period similar to the Black Tower and was similar to it, both in terms of appearance and function. In the lower ward there were permanent quarters for the Glamorgan knights and their grooms and armed men during their garrison service periods. The upper ward was probably filled with residential and economic buildings of the higher nobility and the owners of the castle. A characteristic feature of the entire complex was the small number of towers and the lack of the Anglo-Norman double-tower gates, which clearly distinguished Cardiff from nearby Caerphilly. The defense of the Cardiff Castle was focused primarily on the keep and impeding of access to it, as well as providing a strong garrison, for which was the extremely extensive courtyard of the lower ward.

In the keep, around 1300, a new residential wing with an hall was erected, adjacent to the inner façade of the walls in the south-eastern part of the small courtyard, and a polygonal gatehouse was built, which stood on the edge of the southern slope of the mound. It housed the gate passage in the ground floor and three floors above separated by wooden ceilings, each with a single room. In the ground floor, the entrance in its southern wall was flanked by two arrowslits. In the western wall there was a narrow postern leading to the area between the moat and the mound (berm), while in the northern wall, a pointed portal led to the keep’s courtyard. Originally, the entrance to the first floor of the gate tower was possible only by stairs added from the side of the courtyard and by a passage in the thickness of the wall from the hall first floor, through which you could also reach two latrines. After the foregate was added from the south, another entrance was created in the southern wall. It was closed with a bar sliding into the opening in the wall. The first floor played a defensive role, thanks to two irregularly arranged arrowslits. The second floor was connected to the hall by an external passage, and inside it was equipped with five loop holes. A spiral staircase led to the third floor, as well as a passage to the wall-walk in the crown of the keep wall. Due to the much thinner walls, second storey was much more spacious, therefore, in addition to three arrowslits, in the 16th century it received large windows that allowed for arranging a living room. The gate tower was crowned with an open battle platform, surrounded by a battlemented parapet mounted on corbels. A staircase rose one storey higher, thus obtaining the form of a watchtower and observation post.

The erection of the hall from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries resulted in the reconstruction of the south-eastern wall of the keep, thickened, set on a more massive plinth and slightly protruding towards the slope of the mound. The interior was divided into three storeys by flat, wooden ceilings, set in openings in the wall. On the second floor there was a passage in the wall thickness to the overhanging latrine. The lighting from the outside was originally provided by narrow, almost slit, splayed openings, and perhaps larger windows facing the courtyard. In the 16th century, when defensive considerations lost their importance, the windows in the perimeter wall were enlarged to the form of large, multi-light, four-sided openings.

The entrance to the gate tower created an unusual, 35 meters long and 6 meters wide neck (foregate), led down the mound through the moat, parallel to the transverse wall separating the upper and lower wards (this structure, although unique, was somewhat similar to the foregate of Sandal Castle in England). On the western side of the foregate, a slender, polygonal turret was erected, housing a well, higher than the battlement that crowned the walls of the neck. These walls, despite being built on the slope and at the bottom of the ditch, reached the height of the walls of the keep itself. Their thickness was not the same. The more endangered eastern wall (facing the lower ward) was 2 meters thick, which made it almost twice as wide as the western one (facing the upper ward). The facades were pierced with numerous arrowslits, mainly in the form of cross-oillets. The passage itself was 3.2 meters wide, but at the base of the mound it narrowed to 2.6 meters. It was probably vaulted and could also be protected by loop holes (so-called murder holes) from the level of the upper passage. The southern end of the gate passage in the ground floor was closed with a drawbridge, a portcullis and a gate that could be blocked with a bar. Moreover, behind these obstacles there was a drawbridge, and the section of the passage over the moat was originally covered with planks that could be removed in case of danger. The whole created a unique defensive system, making access to the keep as difficult as possible. On the upper level of the foregate, above the main passage, there was another passage that led to the wall-walk in the crown of the transverse wall and further to the Black Tower. Both floors were connected by stairs in the thickness of the wall, placed behind a drawbridge, opposite the turret with the well.

In the years 1425-1439, during the Beauchamps, new buildings were constructed in the south-west part of the castle, and an octagonal tower with a diameter of 7 meters adjacent to them from the west (Beauchamp Tower). Although it resembled the younger Guy’s Tower from Warwick Castle in England, it had prominent buttresses in the lower parts, characteristic of the South Wales area. It was topped with battlement and machicolation, mounted at a height of about 23 meters on decorative consoles. Every second merlon of the battlement was pierced with a cross-oillet arrowslit, and below, two floors were illuminated with small cusped windows. Near the tower, the walls of the castle touched the city’s defensive wall, which circled in the south of Cardiff and connected with the fortifications of the castle in the south-east corner.

The south-west buildings housed the economic ground floor (located partially below the courtyard level) and two upper representative and residential floors. Their characteristic element was the eastern facade, facing the courtyard with four polygonal turrets – avant-corps. Two of them were pierced with large pointed windows, creating vaulted bay windows, while the second and fourth (counting from the north) housed spiral staircases connecting all three floors. In the 16th century, to the south of the 15th-century polygonal tower (Beauchamp Tower), another, this time a four-sided tower with the sides of 6 meters, was erected, also extended in front of the defensive perimeter towards the ditch.

Current state

The castle has survived to modern times in very good condition, but unfortunately a large part of it was thoroughly rebuilt in the 19th century. The biggest changes affected the south-west wing, the core of which still contains the original 15th-century walls and the polygonal Beauchamp Tower from the 15th century. The outer perimeter wall underwent considerable changes. The towers on the eastern side and the northern gate, stylized as Roman, are also a modern addition, as well as a completely inauthentic passage in the thickness of the wall with pierced windows. Part of the original Roman wall is visible only in the lower parts on the south and north sides, where it ranges from 3.7 to 5.2 meters in height, while the medieval parts have survived in the best condition on the west side and in the west part of the southern section. The most interesting element of the outer defensive circuit is the preserved Black Tower with the 15th century annexes (most of their windows were rebuilt in the 16th century). The tower on the eastern side of the gate is already a 19th-century building. The interior of the castle is dominated by a mound with a Norman keep, one of the best preserved in Great Britain, but unfortunately without any internal buildings.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales, An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Glamorgan, Volume I: Pre-Norman, Part II, The Iron Age and The Roman Occupation, London 1976.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Early Castles, London 1991.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.