History

Caerphilly Castle was built in the second half of the thirteenth century by Gilbert II de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and Hertford, one of the most important magnates during the reign of king Henry III and his successor Edward I. Its construction was associated with Anglo-Norman expansion in South Wales. The task of conquering the Glamorgan region was handed over to the Gloucester earls in 1093, and throughout the 12th and early 13th centuries, battles between Anglo-Norman lords and local Welsh rulers continued. The powerful family of de Clare won the earldom in 1217 and continued to try to conquer the Glamorgan region. Gilbert de Clare inherited family lands in 1263, when the chaos of the civil war in England between Henry III and the rebellious barons grew. In 1265, the Welsh ruler Llywelyn ap Gruffudd allied himself with the baronial faction in England to expand his power in Glamorgan. Gilbert de Clare, in turn, allied himself with Henry III against the rebellious barons and Llywelyn, taking part in the Battle of Evesham and the six-month siege of Kenilworth Castle. The rebellion of the barons was crushed between 1266 and 1267, leaving Gilbert free to expand northwards from his headquarter in Cardiff.

In 1268, de Clare began building a castle in Caerphilly to be able to control his new achievements. The castle was located in the Rhymney valley, in the vicinity of the former Roman fort. Work was imposed on a very fast pace. The architect of the castle and the exact cost of construction are unknown, but modern estimates suggest that it cost the same as the castle in Conwy or Caernarfon, maybe even 19,000 pounds, which was a huge sum at the time. Caerphilly was one of the first concentric castles on the British Isles, preceding the famous Edward I concentric strongholds in North Wales for several years.

In 1270 Llywelyn ap Gruffudd attacked the construction site, burning stored materials and unfinished buildings. The following year, de Clare continued to work on the castle, but he had to accept the royal mediation in a dispute with Llywelyn and let two bishops to join Caerphilly: Roger de Meyland and Godfrey Giffard. By that time, the defensive perimeter of the main part of the castle with the curtain walls, corner towers and gatehouses, and the great hall building had been completed. There were also gates of the outer perimeter, initially connected with wooden fortifications and massive buttresses of the southern dam. After a break caused by attempts to compromise, at the beginning of 1272, Gilbert’s people threw out the mediators, took control of the castle, and the construction continued since 1277. It was possible because a year earlier, Henry’s son, king Edward I, as a result of a dispute with Llywelyn, attacked and deprived him of South Wales, and in 1282 Edward’s second campaign ended in Llywelyn’s death and the fall of independent Welsh rule.

In 1294, Madog ap Llywelyn rebelled against English rule. In Glamorgan, Morgan ap Maredudd, who was disinherited by Gilbert de Clare in 1270, led the local insurgency fight, counting on regaining his lands. Morgan attacked castle Morlais and next the Caerphilly, burning half the town, but could not get the castle. In 1295, Edward I conducted a pacification campaign in North Wales, and de Clare attacked Morgan’s forces at Glamorgan, regaining lost terrain and defeating the enemy. Gilbert de Clare died at the end of 1295, leaving Caerphilly Castle along with the small town in good condition to his wife Joan de Clare and their underage son.

Gilbert’s son, also known as Gilbert de Clare, inherited the castle after the mother’s death in 1307, but died fighting in the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, when he was still young. Care for family grounds was taken over by the English Crown, but before the decisions on the inheritance were made, another revolt in Glamorgan broke out. Due to the actions of the royal administrators, in 1316, Llywelyn Bren, son of Gruffud ap Rhys. His troops in the strength of as many as 10,000 men besieged Caerphilly, capturing of the castle keeper William de Berkerolles, who was just outside the fortifications. Despite this, the stronghold withstood the attack, but the town and nearby mills were destroyed, and the rebellion spread. The royal army had just been sent, defeated Bren at the Battle of Caerphilly Mountain, and eliminated the Welsh siege of the castle. The only damages to the castle was suffered by the south gate and its drawbridge.

In 1317 king Edward II established Eleonora de Clare as the heir of Glamorgan and Caerphilly, who married the royal favorite Hugh le Despenser. He used his good relationship with the king to expand power throughout the region, taking over lands in southern Wales. He also hired master Thomas de la Bataile and William Hurley to enlarge the great hall in the castle. In 1326, Edward’s wife, Isabella of France together with his lover Roger Mortimer, overthrew the hated Despenser authority, forcing the king and Hugh to flee west. The couple stayed in Caerphilly from late October to early November, and then escaped from Isabella‘s upcoming forces. On behalf of the queen, the castle was besieged by William La Zouche, while defenders were commanded by Sir John de Felton and Hugh Despenser the younger. Caerphilly defended itself until March 1327, when the 130-strong garrison surrendered, after the promise of a free pardon to Despreser heir. An exact inventory was made on the occasion of the castle’s surrender, so it is known that in its warehouses there were 800 shafts for lances, 14 Danish axes, 1130 crossbow bolts and 118 quarters of wheat, 118 quarters of beans, 78 carcasses of oxen, 280 carcasses of mutton, 72 hams, 1800 stockfish. Treasure value of 13,000 pounds had to be loaded into as many as 26 barrels and an additional large barrel with 1000 pounds owned by Despreser.

In 1416 castle through the marriage of Isabella le Despenser, first went to Richard de Beauchamp, Earl of Worcester, and then to her second husband, Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Isabella and her second husband invested heavily in the castle, carrying out repairs and making it the main residence in the region. In 1449, the castle went to Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, then to Richard of Gloucester and in 1486 it was taken over by Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke. From that moment, the stronghold began to decline, in the first half of the sixteenth century it was already in ruin, and the surrounding water was transformed into swamps. Only one of the towers was used as a prison for local criminals. In 1593, the castle was rented by Thomas Lewis, who began its demolition to enlarge his home.

When the English Civil War broke out in 1642, an earthwork or a small fort was built near Caerphilly Castle. It is uncertain whether it was raised by the royalist forces or by the army of the Parliament, that occupied these areas during the last months of the war in March 1646. It is also uncertain whether the castle was deliberately demolished by Parliament to prevent its further use by royalists. Although in the eighteenth century, several towers collapsed, it was probably the result of damages caused by slipping, not due to earlier deliberate actions.

The first protection measures were taken by the Marquis of Bute, John Stuart, who owned the castle ruins at the end of the 18th century. Work was continued by his great-grandson, John Crichton-Stuart, who renovated and covered the great hall in the 1870s. The fourth marquis, John Crichton-Stuart, commissioned a comprehensive castle renovation project in 1928-1939. Rebuilt, among others the eastern gate and a few towers. Works on re-flooding the area around the castle were also started and the houses covering the monument were demolished. In 1950, the fifth Marquis of Bute donated the Caerphilly castle to the state.

Architecture

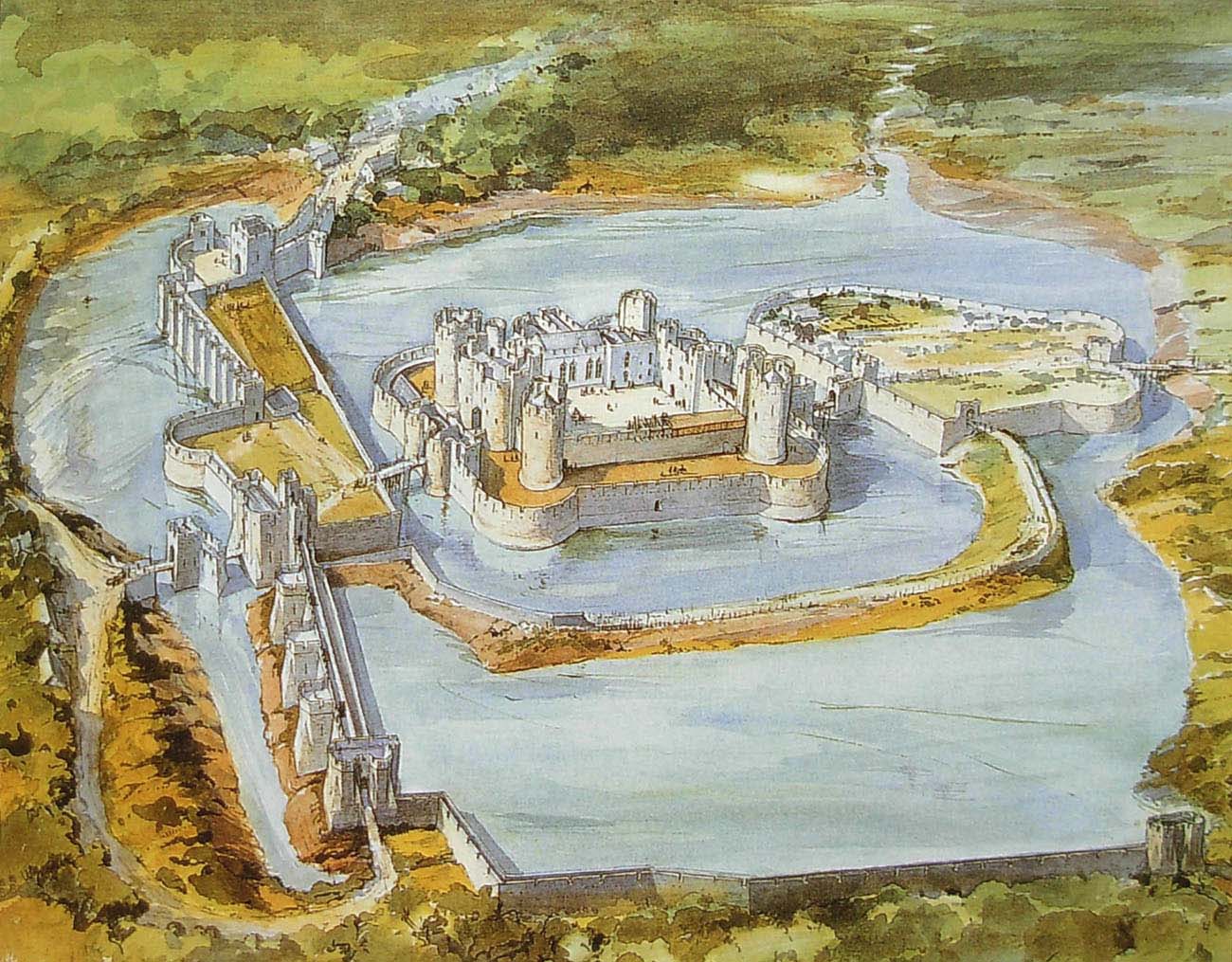

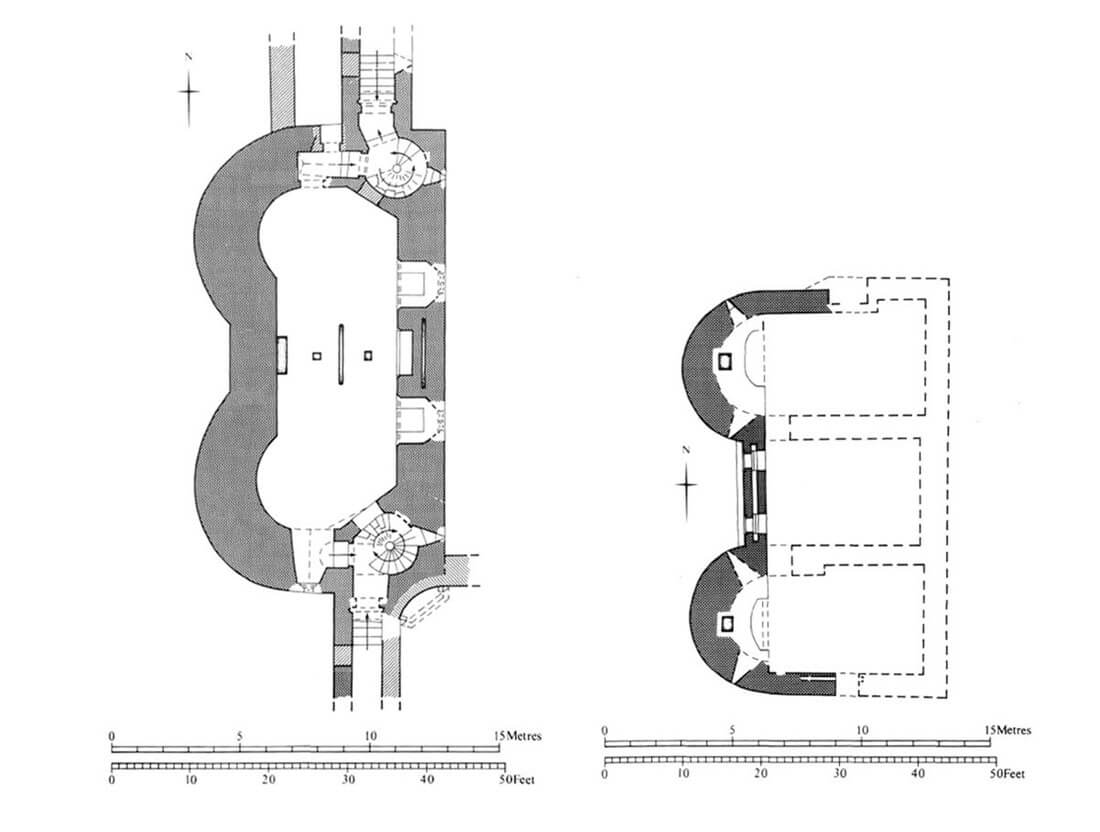

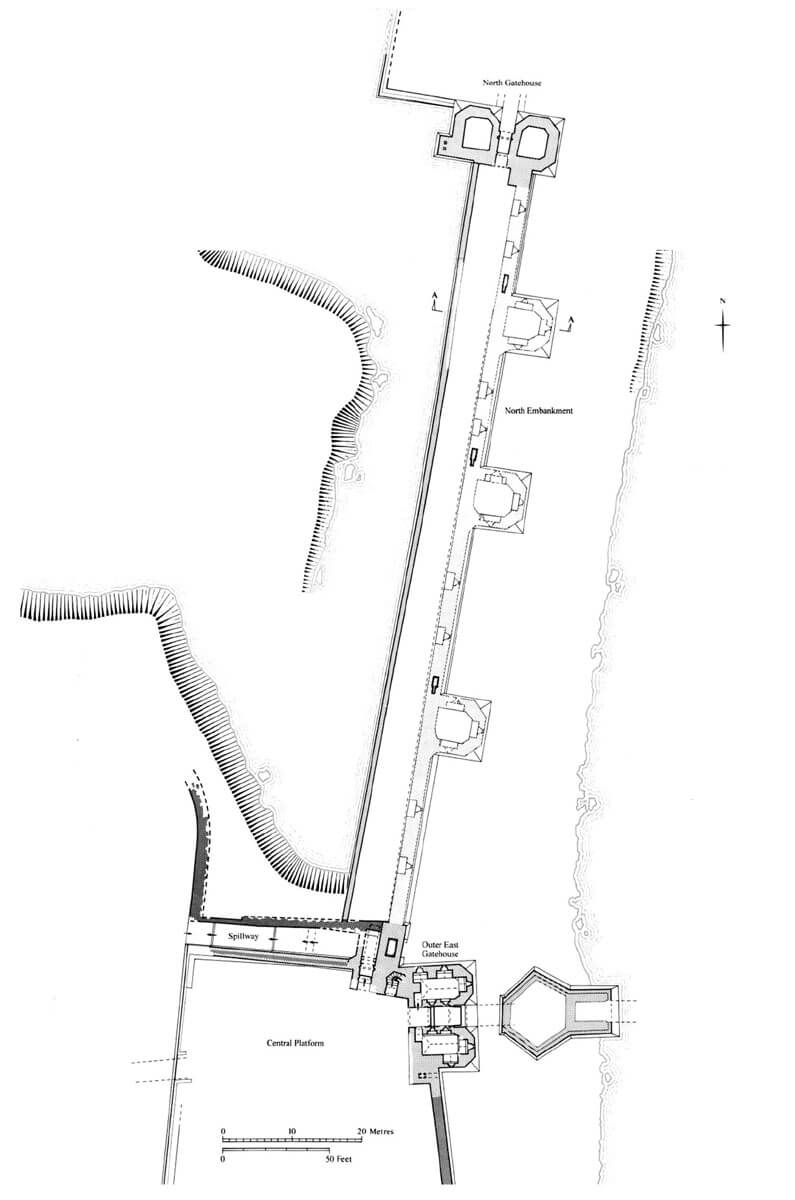

Caerphilly was situated on a relatively flat terrain in a basin surrounded by mountains. On the south-west side was the Nant y Gledyr stream, and on the north, the smaller stream Nant y Risca, connecting with Porset Brook in the east. Undoubtedly, these watercourses were the reason for choosing the location for the construction of the castle, the first, external protection of which was to be a water barrier, not the advantage of height. For this purpose, after creating a series of dams, the central island with characteristic rounded corners and eastern and western insular outworks were built, created by the damming of Nant y Gledyr, transformed into the vast southern lake. It bordered with a slightly higher placed, newly founded town, access to which from the castle led through the eastern island. In the north, Nant y Risca was used in a similar way, with the northern lake separated by a semicircular dyke connecting the east and west islands.

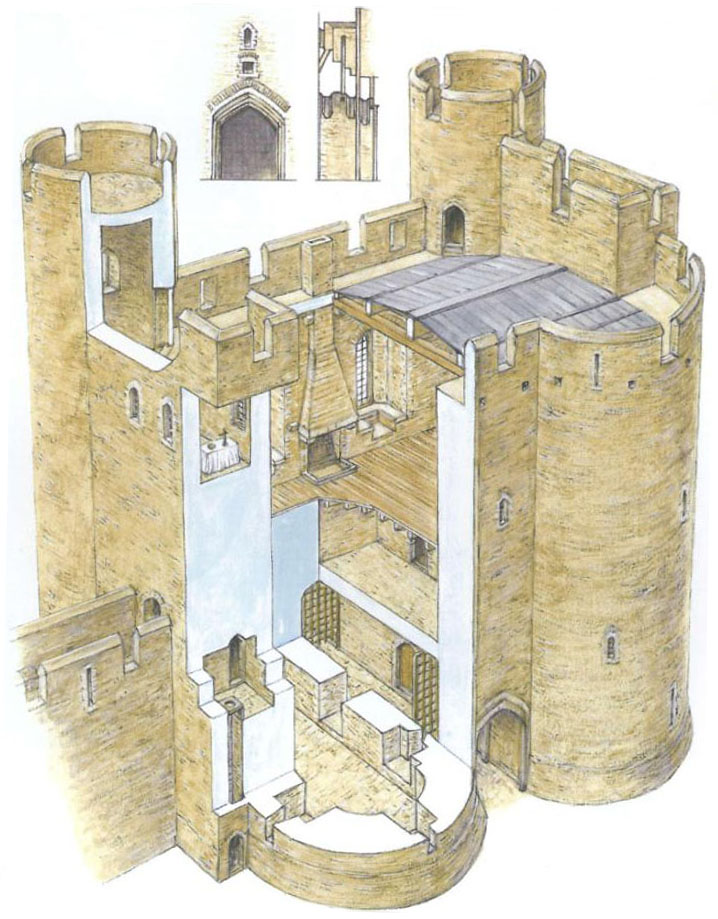

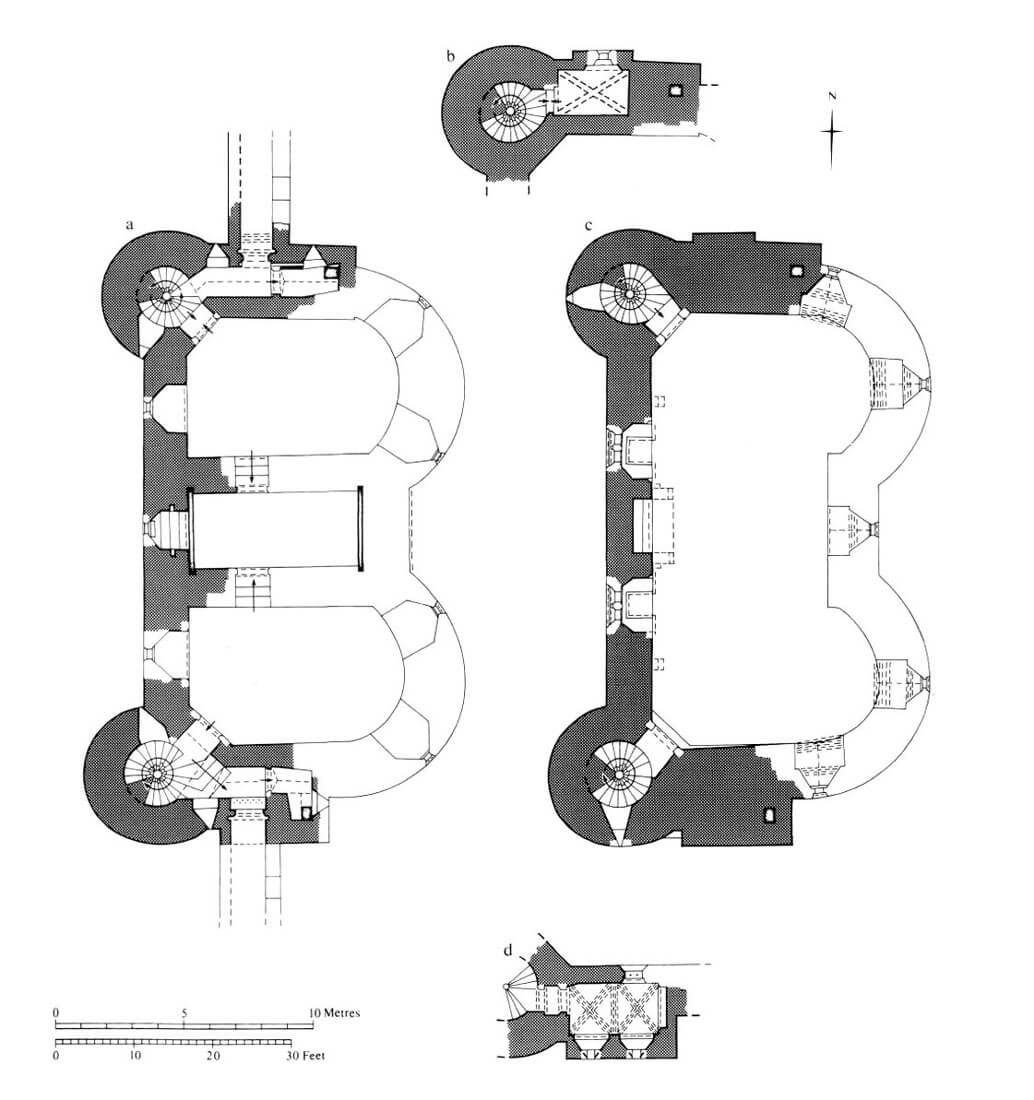

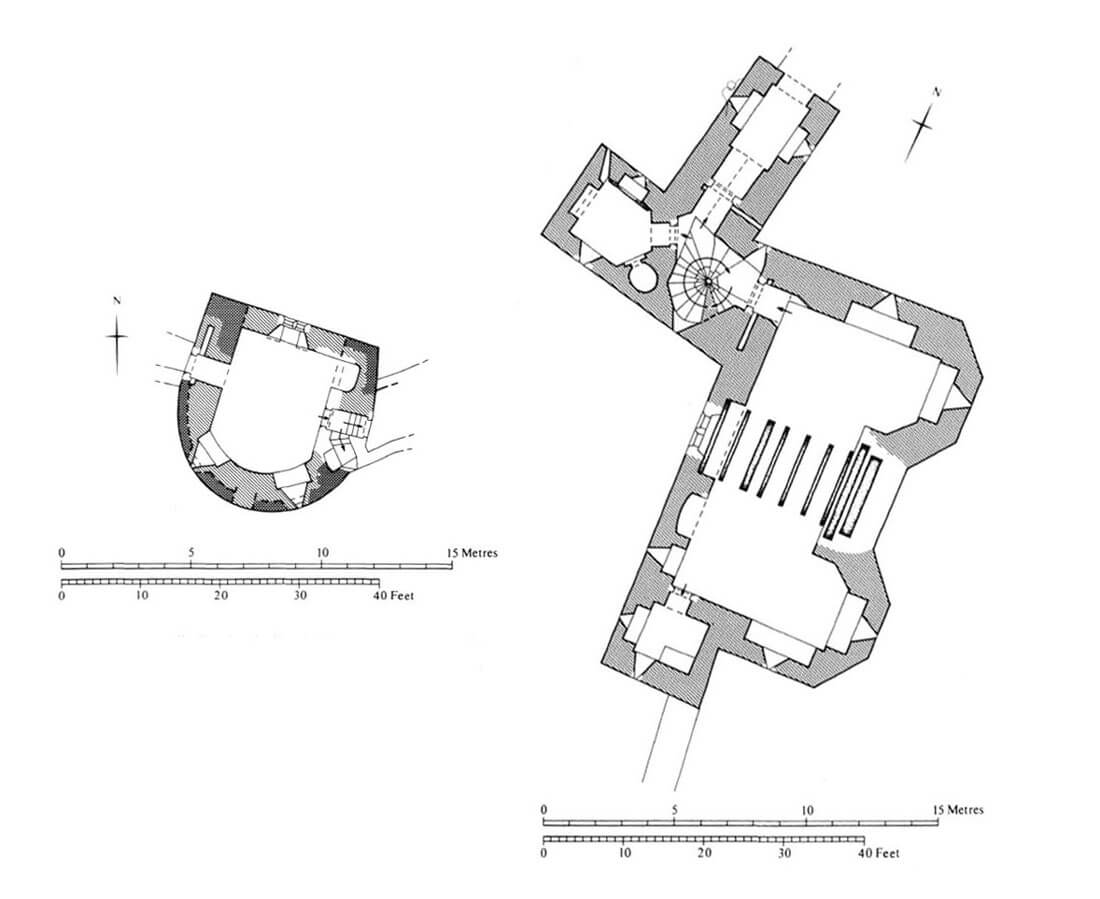

The core of the castle was built of sandstone, on a quadrangle plan measuring approximately 75 x 44 meters, with four cylindrical towers, one in each corner. The entrance led from the east and west through huge gates, each of which was formed of two semicircular towers, protecting the passage between them. They had a system of external and internal defense (from the inner courtyard’s side), in the event of an enemy breaking through in another place, which made them independent defensive works. In their interior there were also living quarters, in the inner eastern gate probably serving the castle constable and his family. Thanks to this, they resembled more massive keeps than typical gatehauses (they could be modeled on very similar gate of Tonbridge Castle in England, while they were preceded the gatehouses in the famous castles of Edward I in Harlech or Beaumaris).

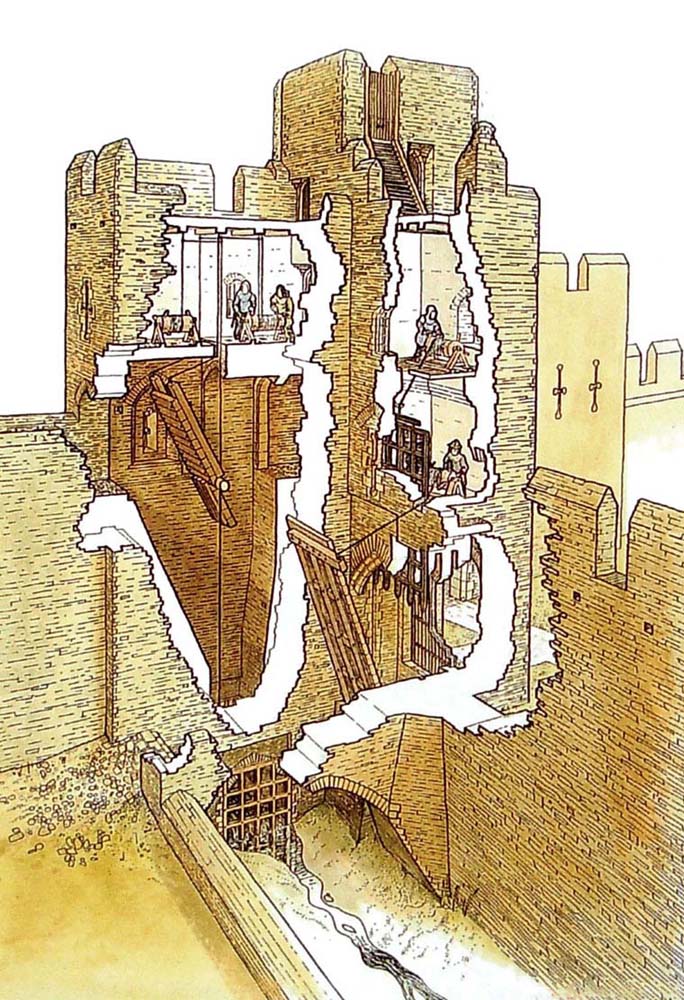

The passage of the inner eastern gate was closed with two heavy doors and two portcullises. From each tower in the ground floor an arrowslit was directed towards the moat, single arrowlits also flanked the passage and the adjoining curtain walls, and in its vault of the gate’s passage there were upper loop holes, so-called murder holes. The only access to the internal rooms led through the side portals (blocked by bars) in the central passage, but one of the door and portcullis sets (closer to the courtyard or closer to the zwinger) had to be passed to them. From the side of the inner courtyard, the gate was equipped with two communication turrets, enabling access to the upper floors and a defensive gallery crowning the gate. The turrets were higher than the gatehouse itself, providing a guard and warning function and connecting with the stairs with short defensive segments, also towering over the main defensive gallery (the northern one was equipped with a privy).

The rooms in the ground floor of the eastern inner gate were illuminated by small windows topped by trefoils, as well as the already mentioned three arrowslits. They probably served the guards. Two rooms on the first floor had a similar form, but a higher standard – they were equipped with fireplaces. Between them, the middle chamber, slightly higher due to the vaulted gateway, contained murder holes and portcullis mechanisms. From the inner courtyard side, under the window, there was also an outlet channel, probably used to shoot attackers or extinguish the fires they put on. The side rooms of the first floor were also connected to the defensive walkway on the adjacent walls, each of these portals was protected by a portcullis. A short corridor nearby led to latrines with outlets in the outer corners of the gate. Most of the second floor was occupied by the main hall of the gatehouse, illuminated by two large, two-light ogival windows, between which there was a fireplace. These windows were placed in deep niches with side stone benches. An open roof truss was used at the top, making the chamber a spacious, impressive hall. In the southern part of the second floor there was a small, two-bay, cross vaulted room, accessible from a spiral staircase. It could have been a small oratory or chapel, or a storage room for valuables, from which by a small window the main chamber could be seen below. A small treasury would be indicated by: bars in the window, two arrowslits on the south side and two doors in front of the staircase. The second small chamber in the thickness of the wall was on the opposite, north side of the second floor. It was also accessible from the staircase, vaulted, but one-bay and without an opening towards the main chamber.

The appearance of both gatehouses of the inner perimeter was very similar, but there were also differences. The western gate, unlike the eastern one, had a pit inside the vaulted passage to which the rear part of the drawbridge was to be hidden when it was raised. It also had two portcullises, but only single gates, placed between the first and second portcullis. Another difference was the two rooms in the ground floor, flanking with single arrowslits the gate passage located between them, accessible not from the gate passage, but from the courtyard. The passage was also protected by two upper four-sided loop holes (so-called murder holes) and one long transverse opening. The side rooms were topped with a rib vault mounted on consoles carved in the image of animal heads. As they did not have fireplaces and were lit only by single small windows with trefoils on the courtyard side, they could not be intended for permanent residence. Rather, they were used as temporary guard rooms and warehouses. Above the ground floor, the west gate had only one floor with a five-bay roof truss. Two staircases led to it, embedded in the thickness of the corner walls, also connected with the upper defensive platform with battlements and the guard porch in the crown of the curtains. The upper room occupied the entire length of the gatehouse, had no windows or arrowslits in the front wall, only from the side of the courtyard the light was provided by two pointed two-light windows, between which there was a fireplace. An additional small window was placed in a recess in the southern wall.

The gatehouses of the outer fortifications of the main castle were similar to the inner one, only lower, and did not have rear communication turrets. Initially, gate towers were open from the back to prevent any attackers from sheltering and to allow fire from the main perimeter of the walls, in case the outer perimeter was captured. In the later, calmer period of the Middle Ages, the rear of outer gates was built up to create additional rooms. Gate towers flanked the central central passage which was controlled by an arrowslits from each tower. Additional slits were directed directly into the foreground, and the third arrowslit of each tower flanked the adjacent curtains of the outer perimeter. Passage was equipped with a drawbridge, which inner part was lowered into a pit and the outer part was raised over the moat. The outer belt of fortifications circled the entire upper ward, adopting semicircular shapes in the corners. In its northern and southern curtain, there were two smaller water posterns, enabling smaller boats to dock to the castle fortifications.

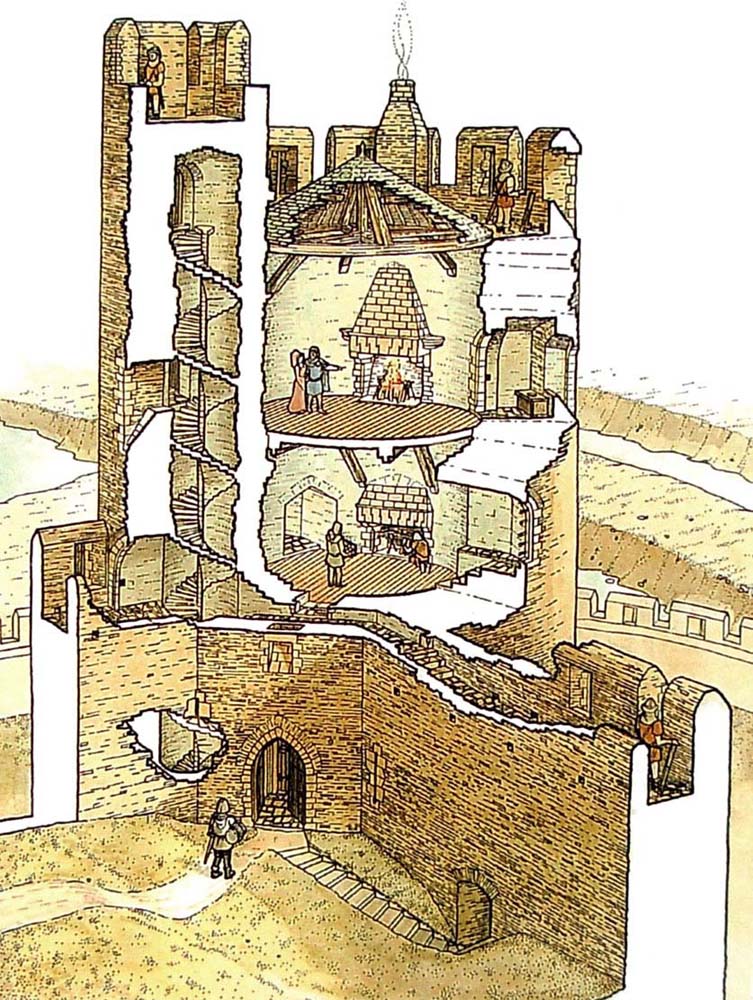

The four corner towers of the main ring of walls were extended in 3/4 of the cylindrical part in front of the defensive perimeter, thanks to which they could flank the adjacent curtains, and their rear parts, facing the courtyard, were straight. They had a diameter of about 11 meters and a height of up to 20 meters. Its storeys were separated by a wooden ceilings mounted on stone corbels, with the top floors covered with conical roofs, around which a defensive gallery ran. The latter was protected by a battlement with pierced openings, through which, if necessary, hoarding porches could be installed.

Probably corner towers had a very similar appearance and internal layout. The best preserved north-west tower was available through the portal in the courtyard’s ground level. It led into a vaulted lobby with a spiral staircase on the left and a latrine on the right. Both the outer door and the door to the staircase were closed with bars embedded in openings in the walls. The north-west tower was the only one that had a latrine in the ground floor, accessible through a separate passage. The ground floor was low and dark, probably used as a warehouse and for defense purposes, as it was equipped with three arrowslits. Two upper floors have already been equipped with fireplaces and small windows from the courtyard side crown with trefoils. The second floor also had a latrine, while from the first floor portal led to a gallery in the crown of the defensive wall. At the portal, a similar hole or channel was placed as at the eastern gate, with the outlet directed centrally above the entrance portal on the ground floor.

The curtains of the walls about 2.4 meters thick, touching the towers and gatehouses, were initially not roofed and had a battlement with splayed internaly arrowslits in the merlons, but after 1271 they were raised, except for those on the northern side, where they remained at the level of the original height with widening of hoarding porch, hung on beams fixed in the breastwork holes. For a change, the southern curtains then housed a vaulted gallery at the level of the old wall-walk and a new defensive porch with battlement. The arrowslits in the former merlons of the lower gallery may have retained their defensive functions for some time, but after the southern tower and the kitchen were erected, they were bricked up. In the ground floor of the eastern part of the northern curtain, near the north-eastern tower, a deep recess, probably a latrine, was placed in the wall thickness. In the western part there was a straight, sectionally topped passage. It was probably not a postern, as the passage was devoid of any jambs or defensive slots, but rather a temporary facilitation of communication during construction works, which was later bricked up.

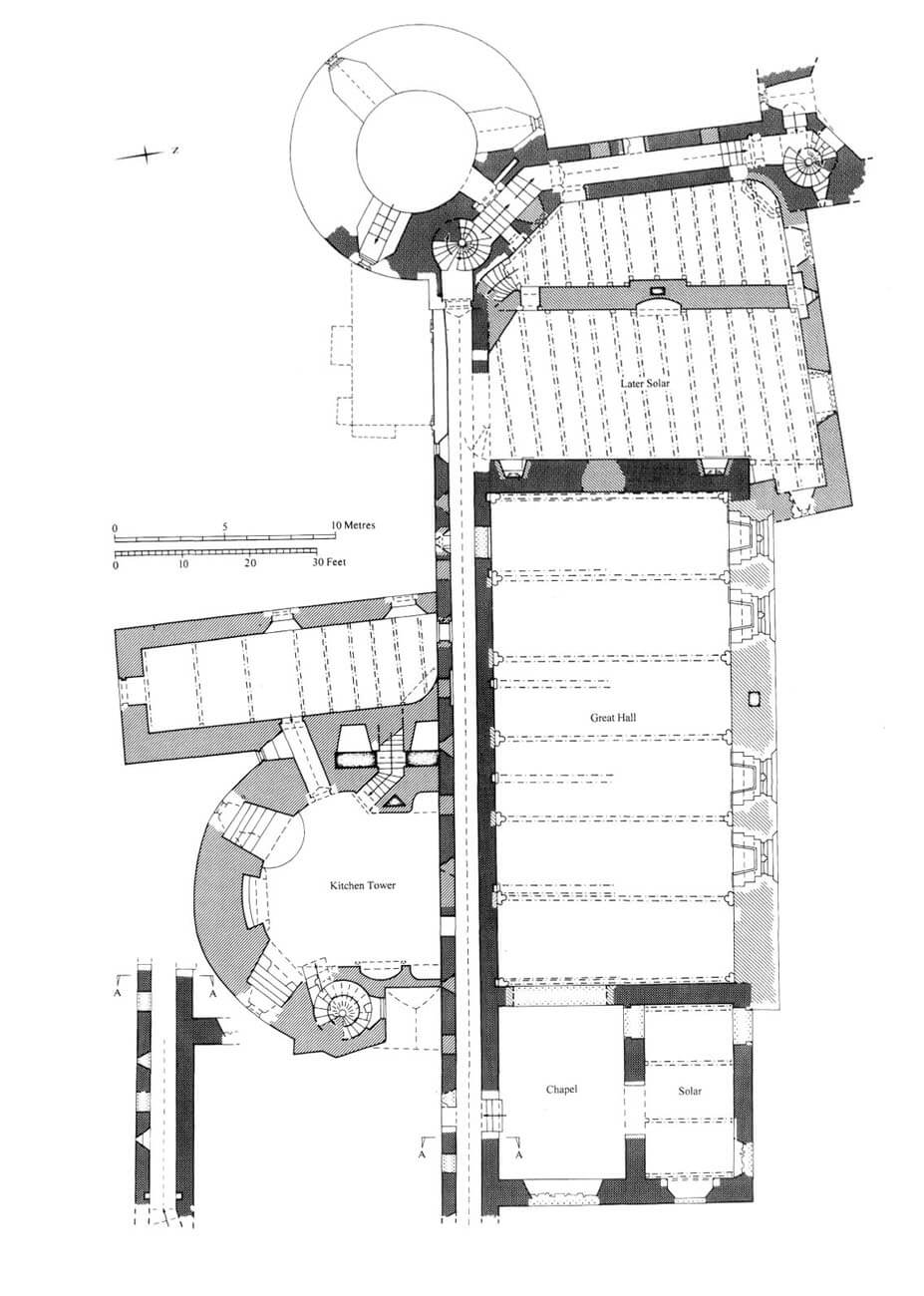

In the inner courtyard, at the southern curtain of the wall, there was a building of a great hall and a building with the private chambers of the castle’s lord in the southwest corner. In the Middle Ages, the great hall (22 x 11 meters) was divided by timber screens (forming a kind of corridor separating the entrance), embellished with colorful decorations and heated by a large, centrally located fireplace, placed between two pairs of large windows topped with ogee arches. Inside, the jamb of these windows were richly decorated with Gothic ball-flowers and moulded. An open wooden roof truss of a considerable width of 10.6 meters rested on stone ancillary columns composed of three shafts based on wall corbels. To this day, some of these corbels have survived, carved in the shape of male and female heads, probably depicting the royal court of the twenties of the fourteenth century. From the great hall, the portal led in the east to the pantry, and in the south, through an oblique passage in the thickness of the wall, to the southern tower (Kitchen Tower). Another portal led to the transverse wing, as well as a passage descending downward further to the water postern by the lake. To ensure safety, both the postern and the portal to the vaulted gallery were closed with portcullises. On the western side of the great hall, probably on a small daise, there was a table at which celebrations, feasts and more ordinary meals were held. Behind it, the portal led to the private chambers of the castle lord. The main entrance was located in the eastern part of the northern wall in a portal richly decorated with foliage and gothic crockets, topped in a ogee arch.

From the west, the castle’s private chambers were adjacent to the large hall, accessible both from the hall and directly from the courtyard. This range was divided on each floor into two rooms: larger from the side of the great hall and smaller in the corner of the castle, connected to the cylindrical tower. The upper, main floor was warmed by fireplaces and illuminated from the courtyard side with large ogival windows. A narrow corridor inserted between the rooms from the courtyard side could be intended for footmen awaiting orders from residents of the main chambers. The lower chambers were also heated with fireplaces (located in the same places as on the upper floor), and were covered with wooden ceilings based on stone corbels placed along the longer walls. The communication with the first floor was provided by stairs in the southern corner of the western room.

To the east of the great hall there was a castle chapel, located on the first floor above the pantries. These two storage rooms on the ground floor level were connected by separate portals with a great hall and illuminated by small four-sided, chamfered windows from the north and east. One of them could be used to store drinks, the other to store food. The first floor was accessed via wooden stairs directly from the courtyard to the chapel vestibule. It is not known whether it was used for religious purposes or was an administrative and utility room. Behind it (closer to the perimeter wall), the chapel was higher than the vestibule and thanks to this it was illuminated by windows of a clerestory with unusual five-sided jambs, filled with quatrefoils. In addition, from the east, from behind the altar, light fell through a large ogival window, also the chapel was open to the vestibule with an ogival opening, and to the hall with an even larger window.

Further buildings were erected in the southern zwinger area. It was a transverse building connecting the great hall with the outer defensive wall on the lake, housing a vaulted passage – the so-called Braose Gallery, the massive horseshoe tower called the Kitchen Tower and the adjoining rectangular building of the castle kitchen, located right next to the south-eastern tower. In the corner at the south-west tower there was yet a small, four-sided latrine tower reinforced with buttresses. The later building was a rectangular economic house on the eastern zwinger. Its base was made of stone, but the upper part was probably wooden.

The transverse building above the vaulted passage descending towards the water postern had two upper floors, each with a long, narrow room, probably for economic purposes, illuminated by a single window from the lake side and covered with a wooden ceiling. The higher room additionally had two windows in the west wall, a fireplace in the north-east corner and a service window pierced between the old merlons of the battlement of the defensive wall.

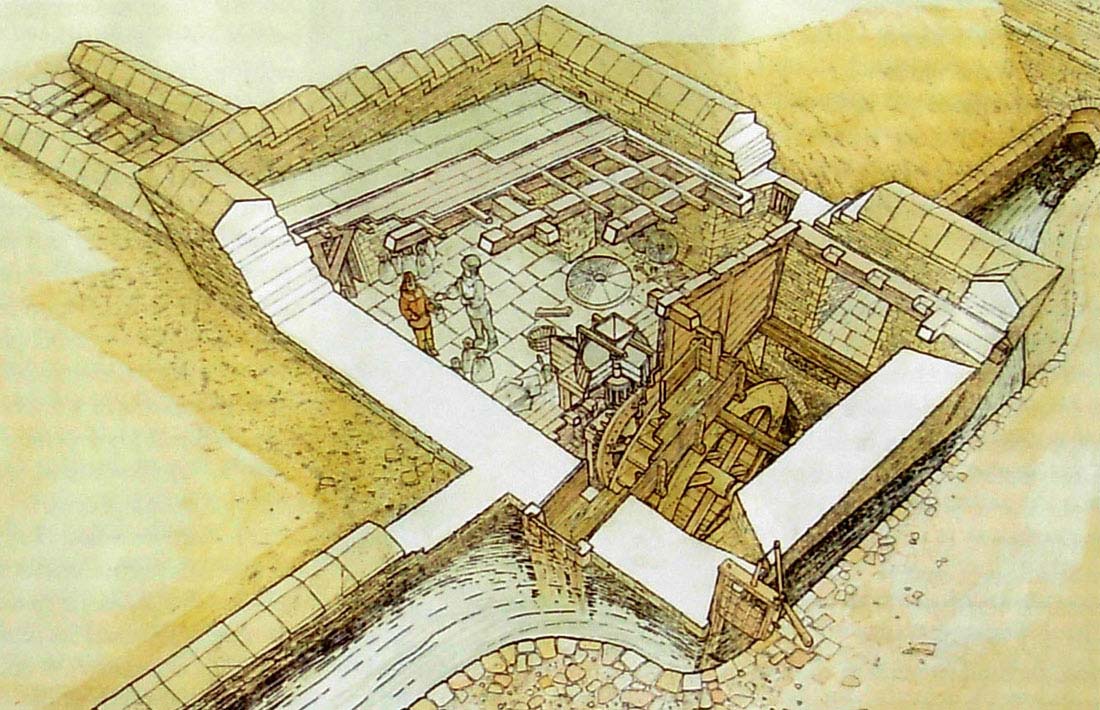

The horseshoe tower in the lower storey had a rib vaulted room. The upper rooms could be used for living purposes, especially in the summer, as it was not shaded by the outer perimeter walls, but at some stage also functioned as a kitchen, equipped with two fireplaces and a waste drain. Later, when the tower was converted into a brewery and a kitchen, fireplace niches and a base for a cauldron or a vat were placed in its ground floor. The tower was accessible through the aforementioned diagonal passage from the hall, which, through the wall, reached the vestibule in the ground floor on the eastern side, located right next to the spiral staircase connecting the floors. The kitchen building, adjacent to it from the east, housed one large room in the ground floor with two fireplaces, a bread oven and a drain outlet directed towards the lake’s waters.

Behind the central island there was a western island, connected from the north-west by a gate and a drawbridge with the mainland, by a second drawbridge in the east with the main castle, and by a side postern with a causeway connecting with the eastern island. All gates were to be connected by a circumference of a low defensive wall (perhaps these fortifications as the only part of the castle were never completed), following an irregular bank in the south and south-west, and in the north-west formed into two semicircular bulges flanking the entrance gate. The island in Welsh was called Y Weringaer or Caer y Werin, which means “people’s fort”, so it could have been used as a refuge for the people of Caerphilly, although its area was probably not covered with larger residential buildings. To the northwest of the island there was a former Roman fort, covering about 1.2 ha.

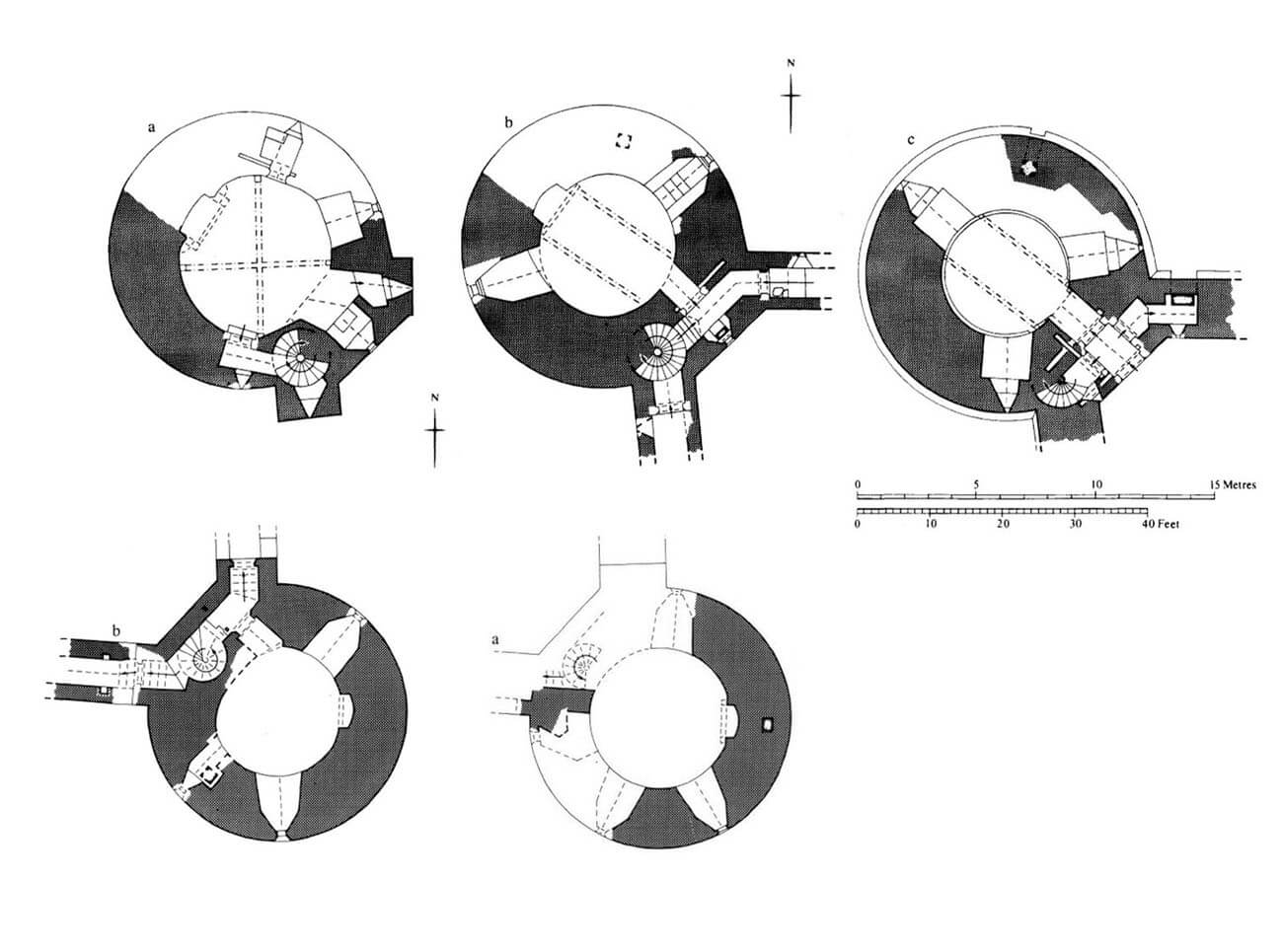

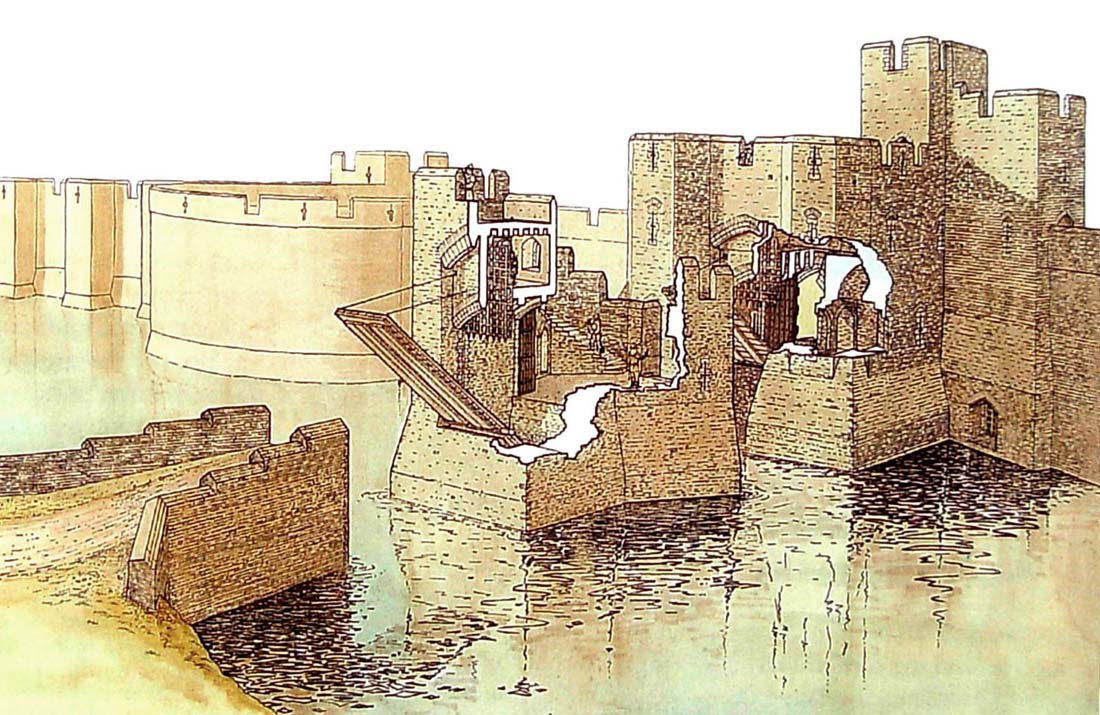

Entrance to the east island was possible through the outer main gate from the east. It consisted of two towers that protected the passage between them. The towers at the base were four-sided, but above they turned into spurs – buttresses that gave them the shape of half an octagon. Each gate tower had three floors with arrowslits, the gate passage was protected by a portcullis, six upper narrow shooting holes so-called murder holes and a drawbridge located in front of the gate passage. On both sides of the gate passage, there were vaulted rooms of guards, accessible only from the passage through the side portals. The arrowslits placed in them covered the moat, the entrance, and the gate itself. The entrance to the first floor of the gatehouse was possible through the west annex, which was also a link with the northern part of the island. Communication to the north was through a drawbridge located over the transverse canal (spillway) connecting the outer moat and both lakes. The canal itself was also secured with a portcullis, but it operated in the opposite way – when raised it blocked the passage and opened the lower spillway. When lowered, it opened the passage and blocked the spillway. At the level of the first floor, the annex was connected with the wall-walk in the crown of the wall, and to get to it, you had to overcome an internal drawbridge, lowered over a 9-meter-high shaft descending towards the spillway, and then a portcullis, similarly to a drawbridge, raised from the upper floor. In the room of the east gate, above the gate passage, there was a mechanism lowering the main portcullis, and another small western room on the annexe first floor probably housed the guard’s kitchen, as it was equipped with a fireplace and a corner stove. A spiral staircase located next to it led to the upper, combat level of the gate, while the staircase itself passed into a guard turret, which was higher by one floor. In the outer central niche above the passage, two square holes housed ropes or a chain used to lift the outer drawbridge, leading to the extended foregate, surrounded on all sides by water. Its octagonal structure was equipped with another drawbridge, connecting the castle with the mainland.

On the north side of the eastern island there was a dam, protected by three massive towers facing east and a double-tower gate facing north, similar to the eastern gate but lower by one floor, also without side rooms of the guards flanking the gate passage, as the base of the gate towers was full. The upper chambers in the towers did not have any openings and were accessible only through hatches in the ceilings of the highest (possibly never completed) storey. On the west side, the gate had a four-sided protrusion containing two latrines chutes directed towards the lake. The narrow, pointedly vaulted gate passage was secured with a portcullis and a drawbridge over the moat, probably resting on the dike in front of the gate.

The role of the dam was to maintain the waters of the northern lake and ensure its proper depth. The three towers protecting it were fully extended in front of the face of the wall and reinforced with spurs – buttresses. For this reason, their bases were quadrilateral, and the upper parts were in the shape of polygons. Interestingly, behind each of the towers (on their northern sides) there were pits, from which wooden footbridges were removed in case of danger to cut off each of the towers from the wall-walk. In addition, each curtain between the towers was pierced with two cross-oillet arrowslits, and both the wall and the towers were topped with a battlement. Inside, each tower had only one chamber, located above the full base (filled with earth). In their walls, three oillet arrowslits were pierced: one directed at the foreground and two flanking curtains to the north and south. The north side of the lake was protected by a long curtain of the wall, bent several times, ending in the west with a small postern with two towers. Probably, its fortifications watched over the mouth of the stream into the pond, which was crucial in maintaining the water barrier.

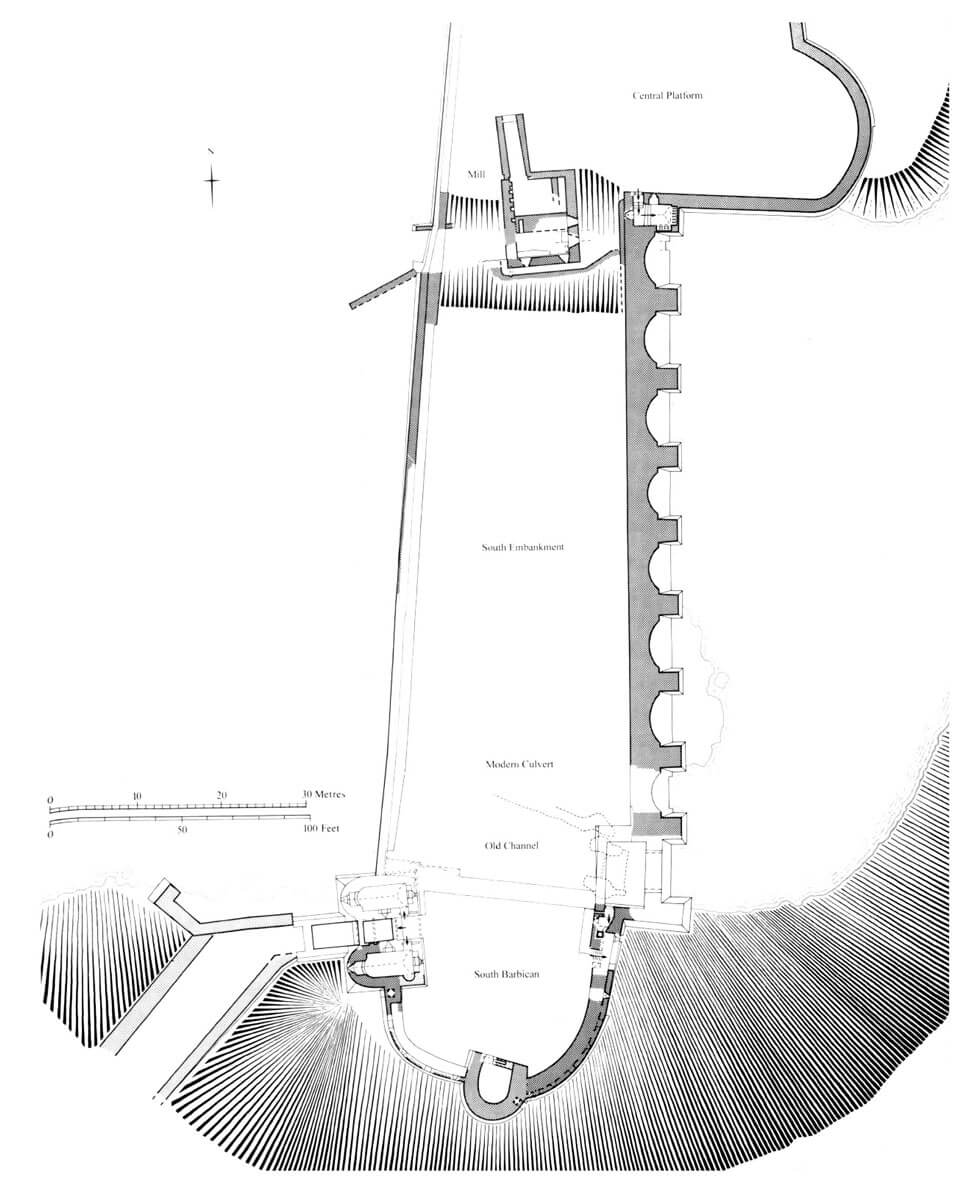

The southern dam was a massive 152-meter-long structure ended with a huge wall with buttresses. On its platform was a water mill for grinding corn, driven by large wheels moved by the water flowing between the lakes. Right next to it there was a small, two-story building in the form of a four-sided turret, with latrines on the ground floor with outlets directed to the moat. This lower, vaulted room was accessible from the ground level, while the upper one was from the crown of the defensive wall through a door blocked with bars. The upper room, apart from the latrine, was equipped with a fireplace. Buttresses up to 91 meters long ended at the so-called Felton Tower, a square fortification intended to protect the lock and regulate water levels. Further, on the southern edge, a horseshoe tower known as the Giffard Tower was erected, to protect the most advanced part of the dam in the form of a barbican, separated from the rest of the dam by a 2-meter thick transverse wall. In western part of the barbican there was a gate leading to the town. It was also a two-tower structure with a passage in the middle, portcullis and a drawbridge, as well as a long neck along the foregate. The drawbridge was placed between two pits, one inside the passage and one between the gate towers, acting as a counterweight.

The water defense zone in Caerphilly was almost certainly inspired by security at Kenilworth, where a similar set of artificial lakes and dams was created. Gilbert de Clare fought during the siege of Kenilworth in 1266 and saw them with his own eyes. The Caerphilly water protection was a special defense against the undermining, which was one of the most dangerous and effective ways to capture castles.

Current state

Surrounded by extensive artificial lakes and occupying a gigantic area of approximately 12 ha, Caerphilly is now the second largest castle in the United Kingdom. It is famous, among other things, for the well-preserved system of medieval dams and locks, which together with the fortifications on the eastern island have been preserved practically in their entirety. One of the towers of the southern gate required reconstruction, as well as the almost completely destroyed four-sided tower called the Felton Tower, which, due to the lack of knowledge about its original appearance, was only partially rebuilt.

The main castle also survived in quite good condition. Until today, all four gatehouses, two of the four corner towers and the third damaged and tilted, have survived or have been reconstructed (the tilted tower among the four corner ones, paradoxically retained the most historic substance, while the inner west gate has survived the early modern period without large losses) . One can admire the roofed great hall and the ruined, but still legible, buildings of the southern zwinger and the building of the castle’s private chambers. Large parts of the corner towers and gatehouses that were destroyed in the early modern period, were rebuilt using original architectural details recovered from the rubble (e.g. fireplaces, jambs of arrowslits and windows) and following the pattern of surviving fragments (e.g. battlement).

The castle is open to visitors from March 1 to June 30 daily from 9.30 to 17.00, in the period from July 1 to August 31 daily from 9.30 to 18.00, from September 1 to October 31, daily from 9.30 to 17.00 and from 1 November to February 28 from Monday to Saturday from 10.00-16.00.

bibliography:

Gravett C., English Castles 1200-1300, Oxford 2009.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Renn D., Caerphilly Castle, Cardiff 2002.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Later Castles, London 2000.