History

Church of St. John was built on the initiative of Bernard de Neufmarché, a Norman knight who conquered the Welsh kingdom of Brycheiniog in 1093. According to tradition he gave the church to one of his supporters, Roger, a monk from the Battle Abbey, who founded a monastery near it. It is more likely, however, that Bernard founded the monastery himself, modeling on William the Conqueror and his monument of victory at Hastings Battle, which was the Battle Abbey. The priory at Brecon would strengthen Bernard’s position as conqueror of Wales.

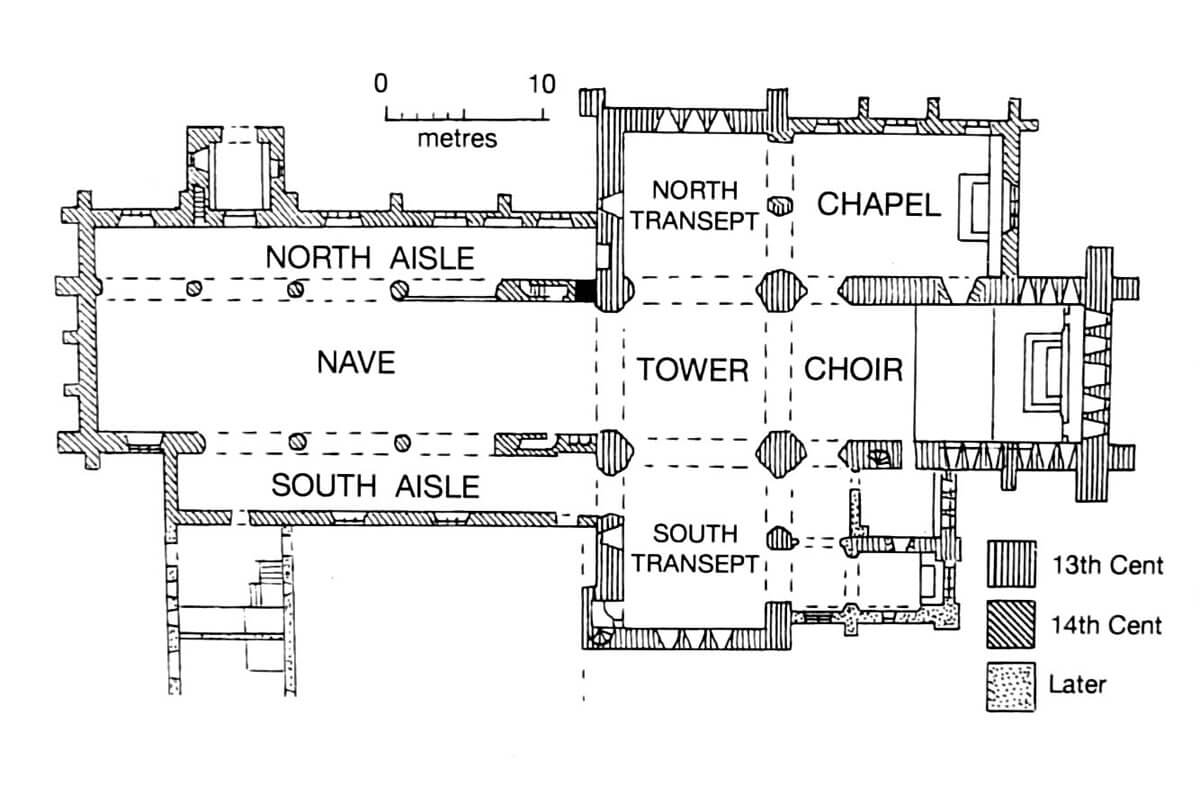

The first prior in Brecon was Walter, a monk from the Battle Abbey. Bernard de Neufmarché also gave the monastery land, rights and tithing from the area, a mill on the Usk River and two more mills on Honddu. After his death, patronage passed on to the Hereford earls, contributing to the further development of the temple. The priory church was rebuilt and expanded in the Gothic style around 1215, during the reign of king John, when the chancel and transept were built. Subsequent works on the nave and enlargement of the church with side aisles, as well as the extension of the cloister buildings were carried out at the end of the 13th and 14th centuries. In the later years of the fourteenth century, the Havard Chapel was added, and in the fifteenth century a magnificent rood screen was founded. The next works on enlarging the buildings were carried out at the end of the 13th and 14th centuries. The roofs, timber ceilings and the top of the church tower were erected in the sixteenth century.

In the Middle Ages, the priory church was famous, because it had an impressive, gilded rood screen, separating the nave from the chancel, which was the object of pilgrimage and worship, until it was destroyed during the Reformation. In 1538, the Benedictine priory was dissolved, the prior was released, and the monastery church became a parish church. Some of the surrounding buildings were adapted for secular use, while others, such as cloisters, were demolished.

In the nineteenth century, the church was in bad condition and only the nave was in use. Minor repairs were carried out in 1836, but a major renovation of the church began only in the 1860s. The tower was strengthened in 1914 due to the occurrence of cracks. In 1923, the church was given the rank of a cathedral.

Architecture

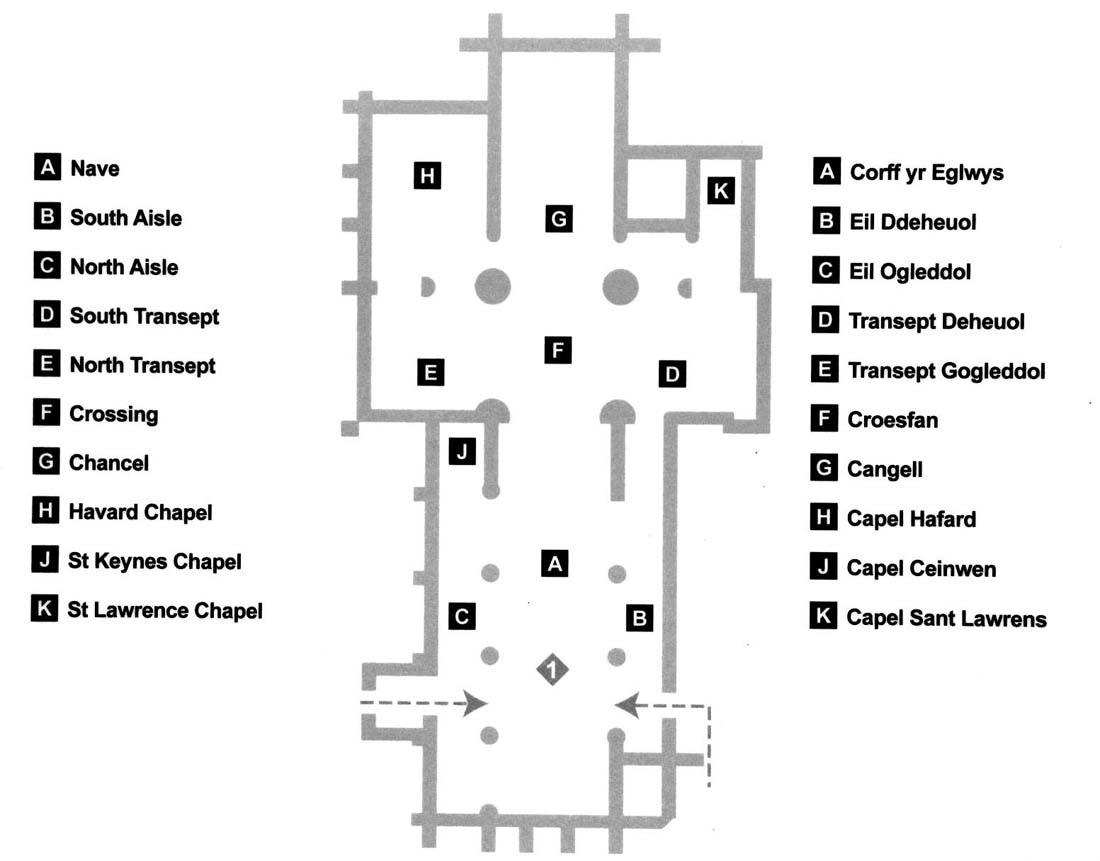

Priory church of St. John, in its late-medieval form, achieved the shape of a basilica on a Latin cross plan. First, at the beginning of the 13th century, a rectangular chancel, transept and a four-sided tower at the crossing (raised around 1510-1520) were built. The three-aisle, five-bay nave in the style of English Decorated Gothic was erected a little later, at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. It was characterized by a very wide central nave in relation to the narrow aisles. In the 14th century, the impressive Havard Chapel was added to the northern wall of the chancel, to the west adjacent to the northern arm of the transept.

The southern aisle was shorter by one bay, which made the west facade asymmetrical. The entrance to the nave was placed in the wall step created in this way. The second portal, leading to the northern aisle, was placed in the 14th-century porch at the height of the second bay from the west. Both side aisles and the central nave were illuminated with large pointed windows with three-light and two-light tracery (on the northern side of the central nave Y-shaped tracery was used). Older, early Gothic windows of the chancel and transept were characterized by much narrower openings, they were also higher. The characteristic eastern façade of the chancel was pierced with five lancet openings, placed in a pyramidal system, and from the south and north, each bay of the choir and the transept were illuminated by three similar openings. The windows were placed between the buttresses, which strengthened the walls everywhere except the southern side of the nave and the transept (there the stability of the structure was ensured by the priory buildings).

The interior of the church in the Middle Ages was not vaulted, it were crowned with a wooden, open roof truss. The central nave was originally separated from the crossing and the choir by a magnificent, richly decorated rood screen (the so-called Golden Rood), equipped with an upper gallery, which was accessed by stairs and passages from the north and south sides. The nave was divided into aisles by high, pointed and moulded arcades, based on massive, octagonal pillars. Originally, the space of the nave was also divided by wooden partitions, delimiting numerous chapels belonging to guilds and wealthy families in the aisles. The space behind the rood screen was available only to monks. In the choir, they had two rows of wooden stalls, and in the southern wall of the chancel, there was an impressive stone sedilia with trefoil tops.

The priory buildings were located on the south side of the nave, with the west end of the southern aisle adjacent to the west range, ending with a quadrilateral residential tower from the south and bordering the cloisters of the inner garth from the east. The entire monastery complex was surrounded by a stone wall with an entrance gate located on the north-west side.

Current state

Today, the church is one of the most important examples of a large sacral buildings in Wales erected in the style of early Gothic (chancel, transept) and late Gothic (nave), although it did not avoid early modern interventions. The chancel vault comes from the nineteenth century, its battlement was also removed, replaced by a parapet mounted on consoles. The southern aisle, sacristy and porch were also partially rebuilt, and a new western window was inserted. A completely modern addition is the south-eastern chapel of St. Lawrence, although the original window from the 13th century was reset in its eastern wall.

Inside the church, among the many chapels that used to be in it, only the northern Keyn Chapel, originally the chapel of the shoemakers’ guild, has been preserved. Unfortunately, the precise descriptions of the structure of the gilded rood screen separating the nave from the choir have not survived. Its scale and dimensions are only shown by the preserved traces of passages to the upper gallery, placed at the end of the nave above the pulpit and on the opposite wall, as well as stone consoles used to support its construction. Among the original furnishings of the church, however, a beautiful, carved, stone baptismal font from the 12th century and the largest stone in Wales, hollowed to store oil needed to light a fire, have been preserved.

Of the former priory buildings, only the former west wing has survived, rebuilt in the early modern period and currently serving as the deanery and vestry. In the 18th and 19th centuries, it was extended to the south, and its tower part was stripped of the top storey, which was later rebuilt in a Victorian style. In the lower storeys of the tower, a 14th-century window topped with a trefoil and the original portal are visible, a few more Gothic windows also have survived on its northern side. Inside, a medieval lobby with a staircase and two fireplaces (one of which was moved from the original place) have been preserved.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.

Website britishlistedbuildings.co.uk, Cathedral Church of St John the Evangelist. A Grade I Listed Building in Brecon, Powys.

Website britishlistedbuildings.co.uk, The Deanery and Vestries, Cathedral of St John the Evangelist A Grade I Listed Building in Brecon, Powys.