History

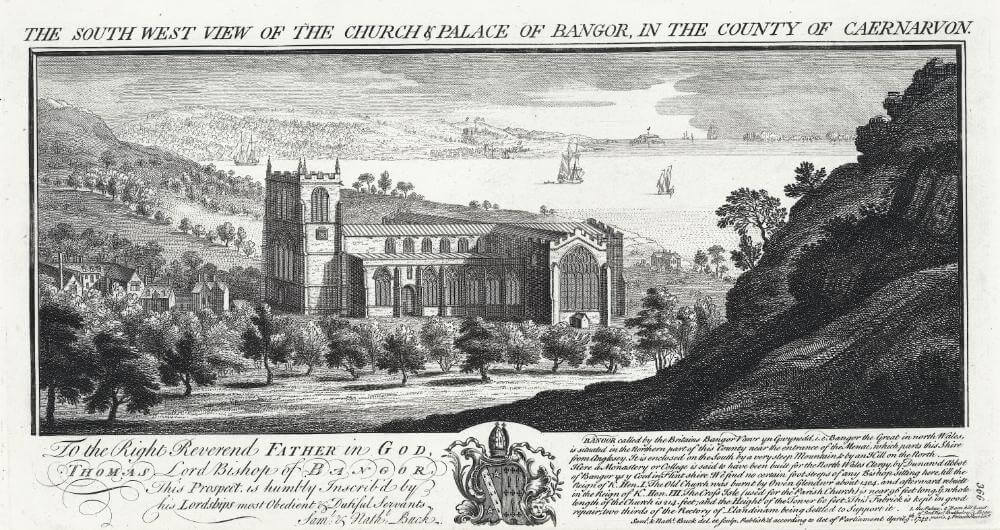

Originally on the site of Bangor Cathedral, around 530, it was monastery founded by Saint Deiniol. It’s monastery church obtained the status of the cathedral in 546, when Deiniol was appointed a bishop of Gwynedd by Saint David. In 634 and again in 1073 the monastery and church was plundered during the invasions of sea pirates.

Burned and robbed by the Vikings, the cathedral was rebuilt around 1130, thanks to the efforts of King of Gwynedd, Gruffudd ap Cynan and the bishop of St Davids. In 1211, the cathedral suffered once more, this time during the invasion of Gwynedd by King John’s troops. During the reconstruction, initiated around 1220 by prince Llywelyn Fawr (Llywelyn the Great), significant transformations were made and, at the same time, the cathedral was enlarged. The next destruction was brought by Edward I’s invasion of Gwynedd in 1282, after which, during the renovation under bishop Anian I, the transept was rebuilt. Work on the nave lasted until the late 14th century, interrupted by the fire of the tower in 1309. In 1386, Bishop Swaffham issued a petition describing that half of the church was still incomplete.

In 1402, the cathedral was to be damaged during the last great uprising of the Welsh against English rule. However, the damage could not be too great, because in 1409 the bishop Nicholls was enthroned in Bangor, although the nave was still unfinished. In the later years of the first half of the fifteenth century, two bishops donated for the building, but in 1468 it was complained that the uprising caused such impoverishment and reduction of income that it was impossible to carry out repairs and complete the construction, despite the fact that the church was in danger of falling into disrepair. The work started more intensively only at the end of the 15th century and at the beginning of the 16th century, on the initiative of bishops Dean and Skevington. Until 1532, the western tower was erected and the nave was covered. The completed church served the Welsh-speaking inhabitants of Bangor at the time.

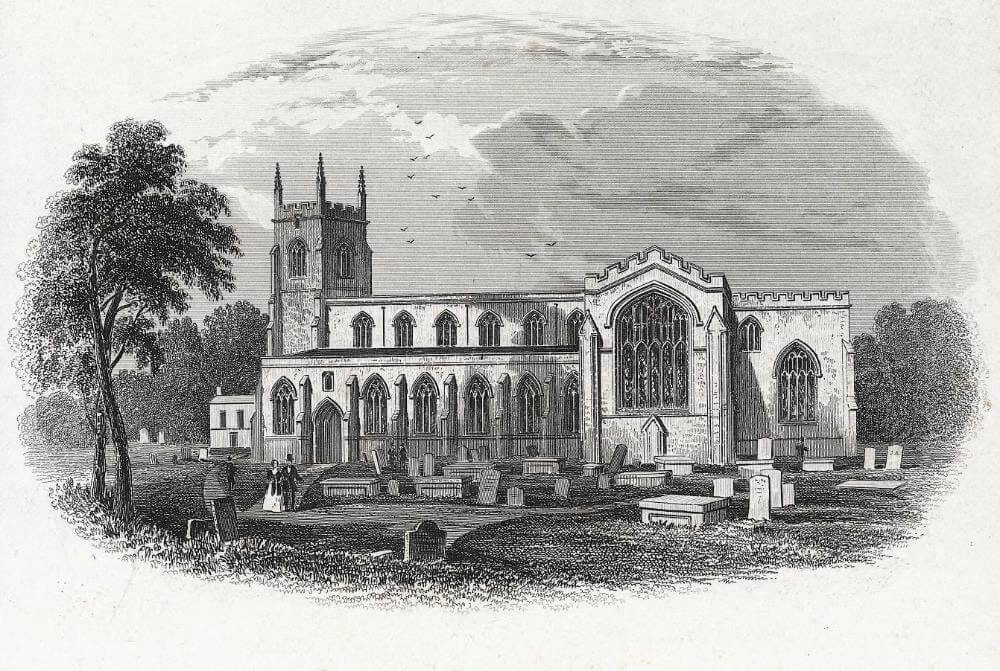

Around the middle of the 16th century, Bishop Bulkeley, the first to reside in Bangor for a long time, restored the roofs of the cathedral, and with his successor William Glynne, he left numerous books that were the nucleus of the cathedral library. At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, bishops Vaughan and Rowland covered the transept and the nave with carved ceilings, although their successor, Lewis Bayly, had to ask in 1630 for help in repairing windows and roofs. In the following years, new furnishings in the cathedral were funded, especially in the chancel and choir, and at the beginning of the 18th century, the chapter house with the sacristy was rebuilt. The great church restoration program was carried out by George Gilbert Scott in 1868–1870, and continued by his son, Jan Oldrid Scott in 1879–1880. It was planned at that time to build a tall central tower with a spire, but due to weak walls, cracks appearing and lack of funds, it was left as a low, unfinished structure. It was not until 1966–1967 that the tower was completed and a pyramidal top was placed on it.

Architecture

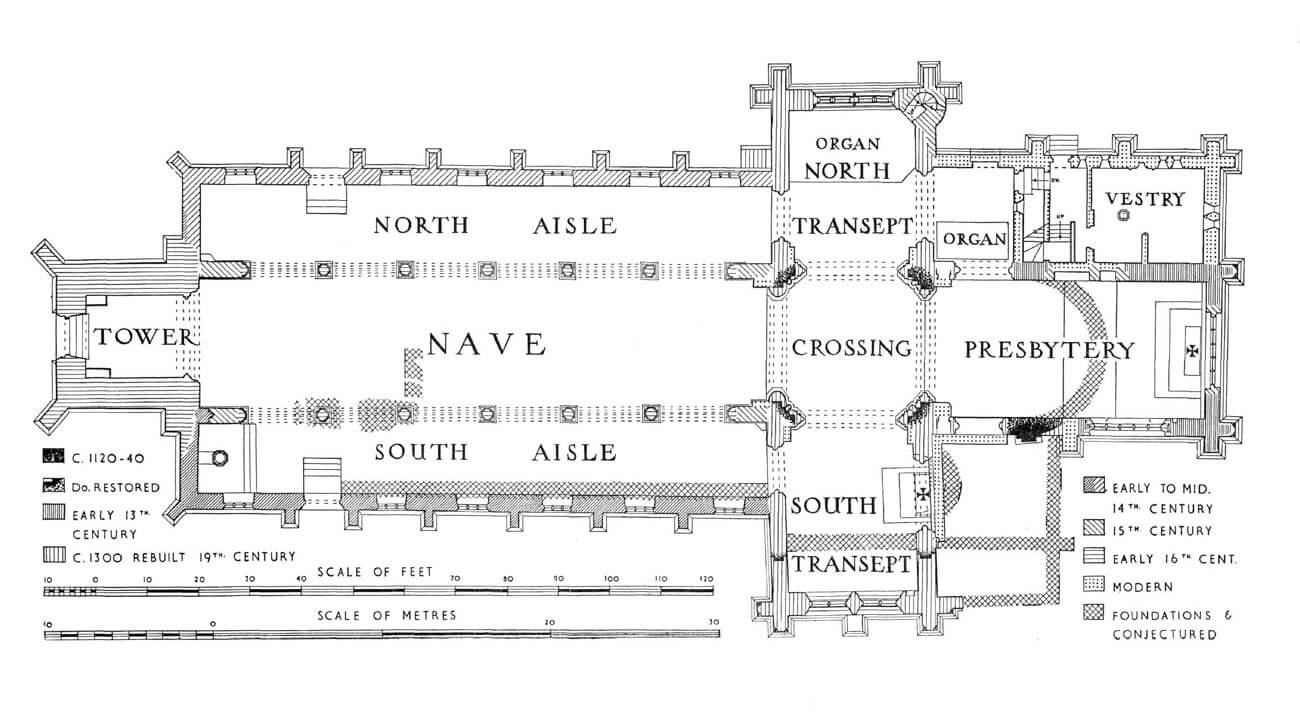

The 12th century cathedral was located on the west bank of the Adda River (Afon Cegin), and also south of the Menai Strait that separates the island of Anglesey from the main part of Wales. It was built in the Romanesque style with aisleless nave and a chancel ending in the east with a semicircular apse. The apses were also located at the eastern walls of the transept, which gave the whole plan the form of a Latin cross.

The reconstruction of the church from the first half of the 13th century resulted in the extension of the chancel and at the same time the removal of the apse, which was replaced with a straight closure. The silhouette of the church was also enlarged at the end of the 13th century by a new transept, thanks to which the whole structure retained the shape of a Latin cross, despite the later enlargement of the nave, which obtained the form of a three-aisle basilica. The new transept was not very symmetrical, as its southern arm was slightly longer than the northern one, it was also deprived of the eastern apses. On the south-eastern side, at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, a chapel measuring 6.7 x 6.1 meters was built, accessible through the eastern wall of the transept and straight from the choir. Further to the south there was an annex of the same length, probably a 2.6 meter wide sacristy (both the chapel and the annex were destroyed in the 15th century). In the fourteenth century, work began on an aisled nave, probably seven-bay, probably never completed in the originally planned shape.

At the end of the Middle Ages, in the first half of the 16th century, the church was given the form of a six-bay basilica by adding aisles, lower than the central nave (33.8 x 7.6 meters), reinforced from the outside with buttresses (unusually the arrangement of the pillars did not correspond to the arrangement of the buttresses, which was related to the reconstruction of the inter-nave arcades in place of the old seven bays from the 14th century). A bell tower on the west side was also built at that time, measuring 5.8 x 4.9 meters. It was erected on a square plan, three-story, with an entrance portal on the west side, two corner, diagonal buttresses and a crowning in the form of a decorative battlement.

Inside, no part of the cathedral was vaulted, the whole was covered with a wooden roof truss. Six bays in the nave were separated by polygonal pillars, between which were built slightly pointed, moulded only from the side of the central nave arcades. Above them, the ogival windows of the clerestory were pierced, divided by mullions into three lights. Slightly larger windows with sharper arches and three-light tracery illuminated the side aisles. The largest windows with rich traceries decorated the gable walls of the transept and the eastern wall of the chancel, where the window was filled with two rows of openings closed with quinquefoils and similar, but smaller traceries in the upper, pointed part of window.

Current state

The oldest preserved fragments of the building come from the 12th century, but they are basically limited to the part of the southern wall of the choir, 4.5 meters high, with a bricked up semicircular window and a pilaster strip. The remaining walls of the chancel date back to the 13th century, except for the upper parts and the renewed eastern window, rebuilt at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. The buttresses, modeled on those from the transept, also had to be restored to a large extent. In the nineteenth century, several carved stones were placed in their walls. The present transept mostly dates from the 13th century (although it was transformed in the 16th century, and was renovated in the 19th century), the nave from the 14th century (with a renovated part of the windows, especially in the northern aisle), and the west tower is a late-medieval from the 16th century. The first floor above the chapter house and vestry on the northern side of the chancel were built only before 1721, the vestry itself was rebuilt and the tower at the crossing of the naves is also an early modern addition.

bibliography:

Clarke M.L., Bangor Cathedral, Cardiff 1969.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals od Wales, Malvern 2012.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Caernarvonshire, volume II: central, the Cantref of Arfon and the Commote of Eifionydd, London 1960.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.