History

The Benedictine priory and church of St. Mary were founded in Abergavenny in the late 1080s or 1090s by the first Anglo-Norman Lord of Abergavenny, Hamelin de Ballon, who had been granted the lordship of northern Gwent and Abergavenny Castle by King William II. The building probably stood on the site of an earlier Romano-Celtic place of worship, but from the beginning it had close links with the Anglo-Norman lords. The priory was originally also subject to the mother monastery of St. Vincent and St. Laurence of Le Mans in France. It became fully independent before 1189, although the two monastic houses maintained mutual links in subsequent years.

The priory was originally a small house, but through donations from the Lord of Abergavenny, William de Braose, it grew to a congregation of thirteen monks in the second half of the 12th century. Successive local lords were also benefactors of the priory. In the late 12th century its prior was Henry of Abergavenny, who was elected Bishop of Llandaff and later an assistant at the coronation of King John I in 1199. However, by the early 14th century the priory and its buildings were in a state of decline. It was staffed by only five monks, accused of various offences, including leaving the cloister, gambling, breaking the fast, and trying with women. The situation was so serious that the prior, Fulk Gastard, accused of perjury, stole the monastery’s valuables and fled when he heard of the bishop’s visitation.

Around 1319-1320, the patronage of the priory was assumed by John de Hastings, Baron of Abergavenny, who, with the consent of Pope John XXII, renewed and reformed the monastery, installing a prior and twelve monks. Richard of Bromwich, a monk from Worcester, was appointed the new superior. In addition, the monastery church and the cloister buildings were thoroughly rebuilt and enlarged from the lord’s foundation, and the property was expanded with new land grants and privileges. However, in the mid-14th century, due to the outbreak of the Hundred Years’ War, King Edward III took over the property of all the monasteries that had links with foreign abbeys. The Benedictines of Abergavenny regained their income in 1360, but lost it again nine years later, due to the beginning of another phase of warfare. The economic situation of the monastery was also significantly worsened in the second half of the 14th century by the Black Death epidemic.

In 1403 the monastery burned down during the Welsh rebellion led by Owain Glyndŵr, losing all its books, documents, movable property and valuables. Several brethren then returned to Le Mans, and the situation in the following years was so bad that in 1411 the prior William Peyto, with the consent of King Henry IV, had to ask the French monastery for three additional monks in order to be able to celebrate mass. The priory buildings must have remained in ruins until around 1428, when Pope Martin V granted indulgences to finance repairs. In the following years the reconstruction and functioning of the priory was supported mainly by local wealthy townspeople, thanks to whom, among other things, new bells were purchased for the church.

By the time of the Reformation, the priory had only four monks and a prior, who had an estimated income of £129, derived from the leases of houses and shops in the town, mills, lands, the surrounding rectories, and the manors at Monktown, Hardwick and Llwyndu. Due to the close links between the rulers of Abergavenny and the Tudor dynasty, and because of the school operating at the priory, its church was spared and became a parish church, while the priory buildings passed to lay people, which eventually led to their extensive reconstruction. In 1828-1829 the two aisles of the church were combined into one large space for Protestant preachers, with side galleries for the congregation. These changes were removed between 1881 and 1896, when the church underwent a neo-Gothic renovation and partial extension.

Architecture

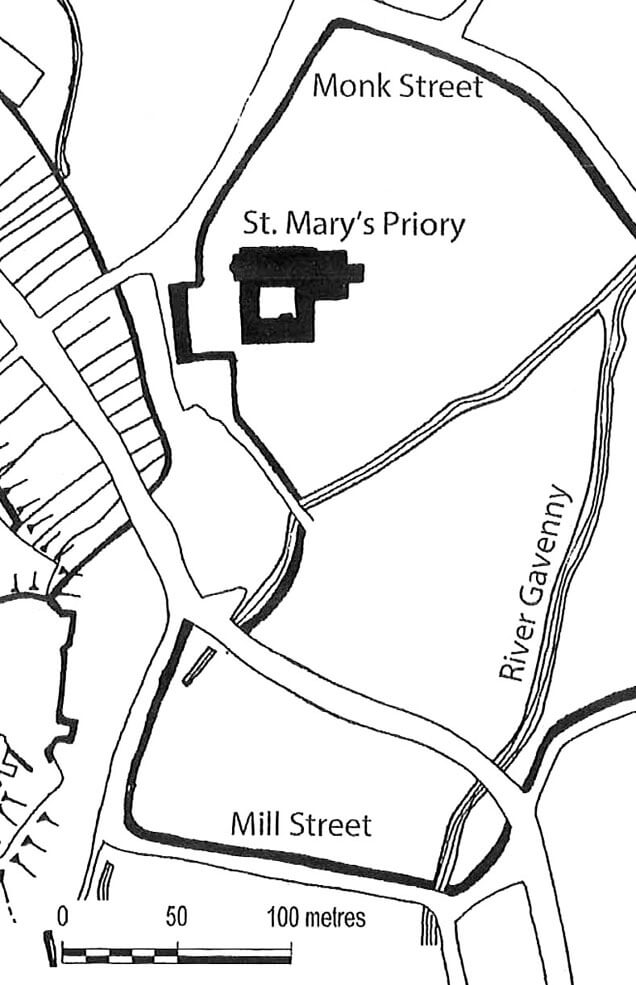

The priory was founded on the north-eastern side of the castle, and at the same time on the eastern side of the medieval town, outside its original wooden and earth fortifications and defensive walls from the second half of the 13th century. The town limited the Benedictine lands from the west, while to the east the monastery area reached the meridianally flowing Gavenny River, which had its mouth on the Usk River a few hundred meters away. On the northern side, a road ran by the priory leading to one of the town gates. The monastery occupied a much larger area to the south, where it reached the mills under the castle hill.

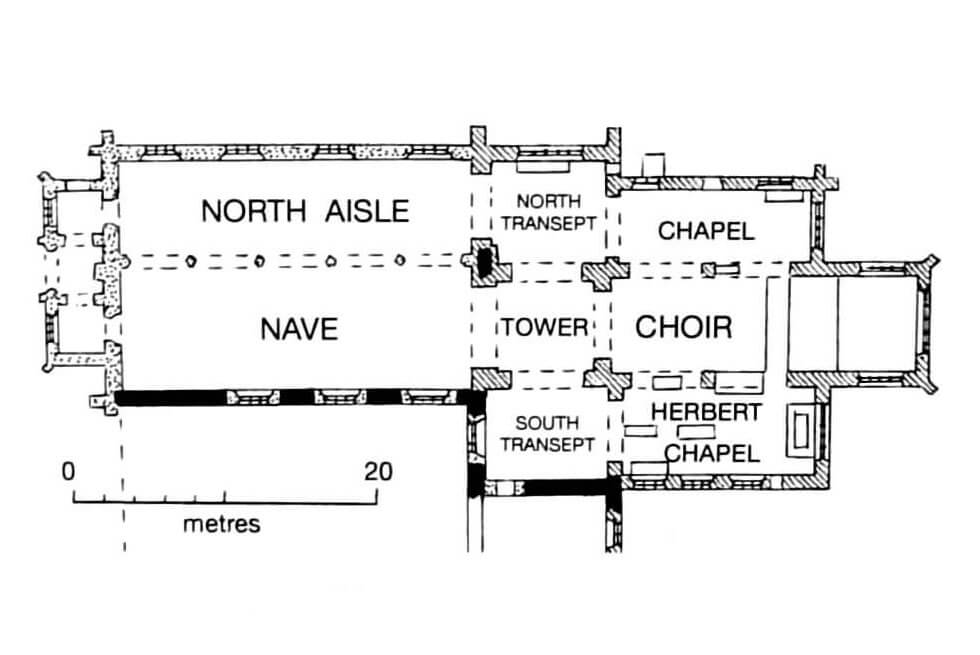

The monastery church from the 14th century was built on a Latin cross plan, consisting of an aisleless nave about 52 meters long, a rectangular chancel of a similar width to the nave and two arms of a relatively short transept, with at least the southern wall of the nave and transept using older walls from the 12th or 13th century. At the crossing a quadrangular tower was erected, narrower than the transept, equipped with a slender corner communication turret. Two rectangular chapels were added to the sides of the chancel in the 14th century: St. Joseph’s Chapel on the north side and St. Herbert’s Chapel on the south, both opening with two arcades to the interior of the choir. Probably in the late Middle Ages, an aisle was added to the north of the nave and covered with a common gable roof with the older part of the church.

The priory buildings were on the south side of the church, located in such a way that the eastern range was adjacent to the southern arm of the transept, and the cloister’s garth was to the south of the nave. The layout of individual rooms remains unknown, and it is also uncertain whether the full, three-winged complex of buildings, as provided for by the monastic rule, was built. It can only be assumed that traditionally in the eastern wing there was a chapter house in the ground floor, and a dormitory on the first floor, connected directly with the church transept. To the west of the church and enclosure, there were farm buildings of the monastery, including a barn.

Current state

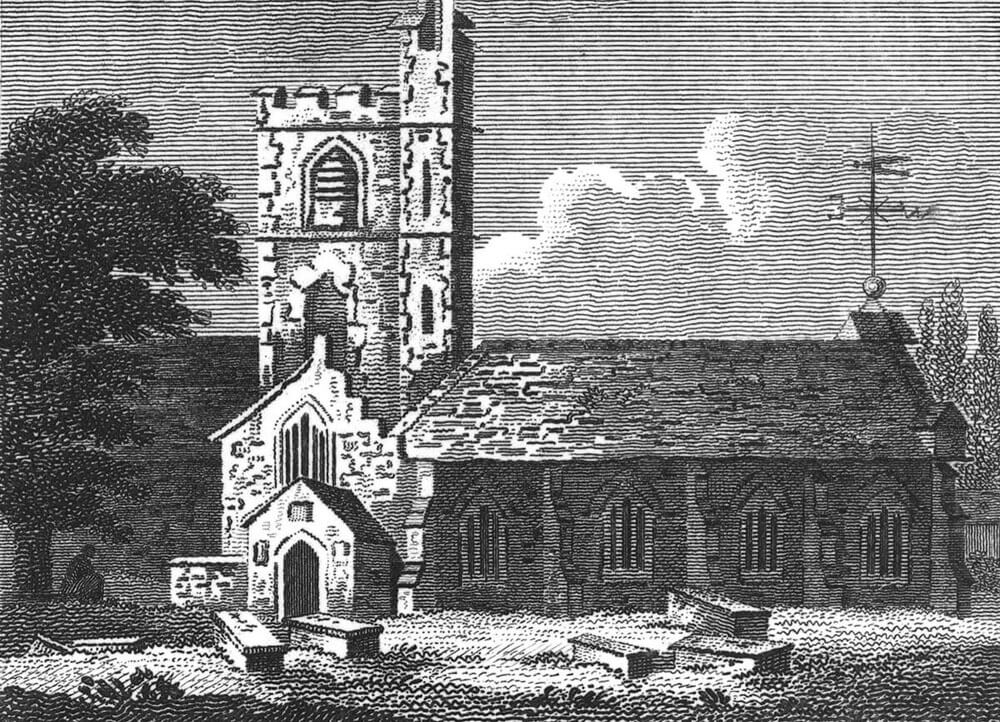

The church, preserved to this day, represents the style of English decorative and perpendicular Gothic. Unfortunately, few elements from the Norman period have survived, and the church underwent significant changes in the early modern period, which influenced its appearance. The nave was rebuilt to the greatest extent, with the northern part built from scratch in the 19th century. The medieval western façade was also removed, first transformed into a Baroque one, and then into a neo-Gothic one, preceded by a wide modern porch. Many window openings have been transformed, especially in the nave. The windows in the eastern wall of the chancel and chapels are from the 15th century or are contemporary copies of them, as is the five-light window in the northern wall of the transept. The arcades under the tower and the arcades between the chapels and the chancel have survived from the 14th century.

Of the buildings of the medieval claustrum, the eastern wing has partially survived, with an eastern lancet window at the height of the dormitory and with the original entrance portal. Other windows, now bricked up, date mainly from the 16th and early 17th centuries. The former monastery barn has also survived to the west of the church, with the core of the walls dating from the mid-14th century, rebuilt after burning down in the early 15th century and unfortunately transformed into an early modern residential house in the 16th or 17th century.

The original furnishings of the church include 15th-century oak stalls with blind tracery decoration on the front and back, a 15th-century wooden carving of the Tree of Jesse (probably part of the old reredos) and one of the largest collections of valuable medieval tombstones in Wales, the oldest and most valuable of which are of Eva de Braose from the second half of the 13th century, John of Hastings, Lord of Abergavenny who died in 1325, Sir Lawrence Hastings and Sir William de Hastings, both died in 1348, and Sir William and Lady Gwladys from the mid-15th century.

bibliography:

An Anatomy of a Priory Church: The Archaeology, History and Conservation of St Mary’s Priory Church, Abergavenny, red. G.Nash, Oxford 2015.

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

Salter M., The old parish churches of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.