History

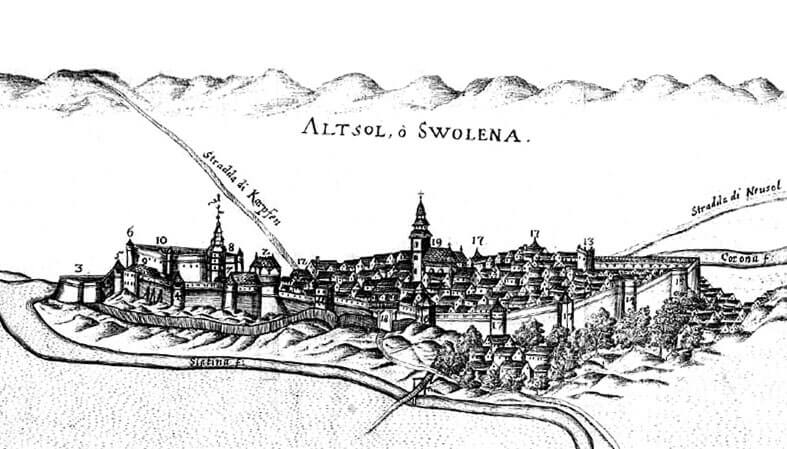

King Louis I of Hungary often visited the city of Zvolen, spending time hunting in the surrounding forests. Since the Empty Castle over the city was difficult to access, and its interior too modest, at the end of his life the king ordered to erect a new castle in Zvolen, which was built in the years 1370-1382 on the place of an older manor. It was to perform a residential and representative function for the king and his court. After the destruction of Empty Castle in the middle of the 16th century, the capital of the Zvolen county was also moved here. The castle served this function until 1776, when the office was moved to Banská Bystrica.

Construction works on the castle were probably completed or close to completion in 1380, when in Zvolen King Louis the Great met the Austrian Prince Leopold III Habsburg, with whom he agreed on the marriage of their children, Hedwig and William. At the end of the same year, Louis welcomed the Czech king Wenceslas IV and the Italian cardinal Pileo de Prato in Zvolen. In 1381, at the request of the townspeople of Zwoleń, he allowed the collection of fees from workers and members of the court, if they imported wine not for their own needs. The castle, or rather the manor, was also recorded in documents in 1382, when the oath of allegiance “in Zolin curia suae” was taken frm the representatives of the Polish nobility. The recurring term manor probably referred to the non-defensive function of the new building at that time.

At the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, the castle in Zvolen became a popular place for Louis’ successor, Sigismund of Luxembourg. New ruler often stayed in the town and also started the tradition of handing the castle over to subsequent queens. In 1424, he gave the local estates to his wife Barbara, who derived income from them and sought shelter in dangerous times (in 1430, out of fear of the Hussites, she ordered cannons and gunpowder to be brought to Zvolen). Later castle passed into Barbara’s daughter, Elizabeth, wife of Albert Habsburg. When, after Albert’s untimely death, a civil war broke out on the Hungarian throne, the widow called John Jiskra for help, who made Zvolen its headquarter. He occupied the castle in the years 1440-1462, but castle was besieged in 1447, when the Hungarian governor Jan Hunyady led the offensive against Jiskra’s castles. The next battles took place in 1451, when Hunyade’s army burned the town down, and placed a siege camp in front of the castle. Despite this, it was only in 1462, under the agreement of Jiskra with Matthias Corvinus, that Zvolen returned to the royal hands.

After the death of the king Matthias Corvinus, the widow queen Beatrice received castle along with the whole county and mining towns, as a supply from Vladislaus II of Hungary. Next, it was owned by another wife, Anna, who gave it to John Thurzo, a mining entrepreneur from Banská Bystrica, as a pledge for the loan. Thanks to Thurzo, the castle was rebuilt and strengthened. In 1515, the Hungarian ruler ordered mining towns to obey the zupan of Zvolen and the Kremnica administrators of the Mining Chamber, Juraj and Alex Thurzon, especially regarding the construction works carried out at that time. In 1522, Louis II donated the castle to queen Maria Habsburg, who in 1548 gave it to his brother, king Ferdinand I, thus ending the female rule in Zvolen.

Another reconstruction, carried out after 1548 in relation with the Turkish threat, turned the Zvolen Castle into a Renaissance fortress. The castle crew was paid by the inhabitants of the mining towns, and the command was carried out by the local zupans. In the second half of the 16th century, the command of one of the military districts was located in Zvolen, and its commander, or captain, lived in the castle. Thanks to its fortifications, Zvolen avoided the havoc by the Turks, who at the end of the 16th century regularly plundered the surrounding villages, reaching all the way to Banská Bystrica. Neither the castle nor the city resisted the Hungarian insurgents. They won Zvolen during the uprisings of Bocskay, Bethlen, Thókoly and Rakoczi. The army of the Rakoczi, retreating in 1708, did great damages to the town.

In 1636 the castle was bought by the Esterhazy family; it remained their property until the beginning of the 19th century. They did not make any significant changes to it, they only rebuilt the chapel and made some small adjustments in the decor. In 1805, the castle was bought by the state, it housed, among others, offices, court, school, barracks and tobacco warehouse. In the years 1894-1906, the object was renovated, at the same time being considered as a monument.

Architecture

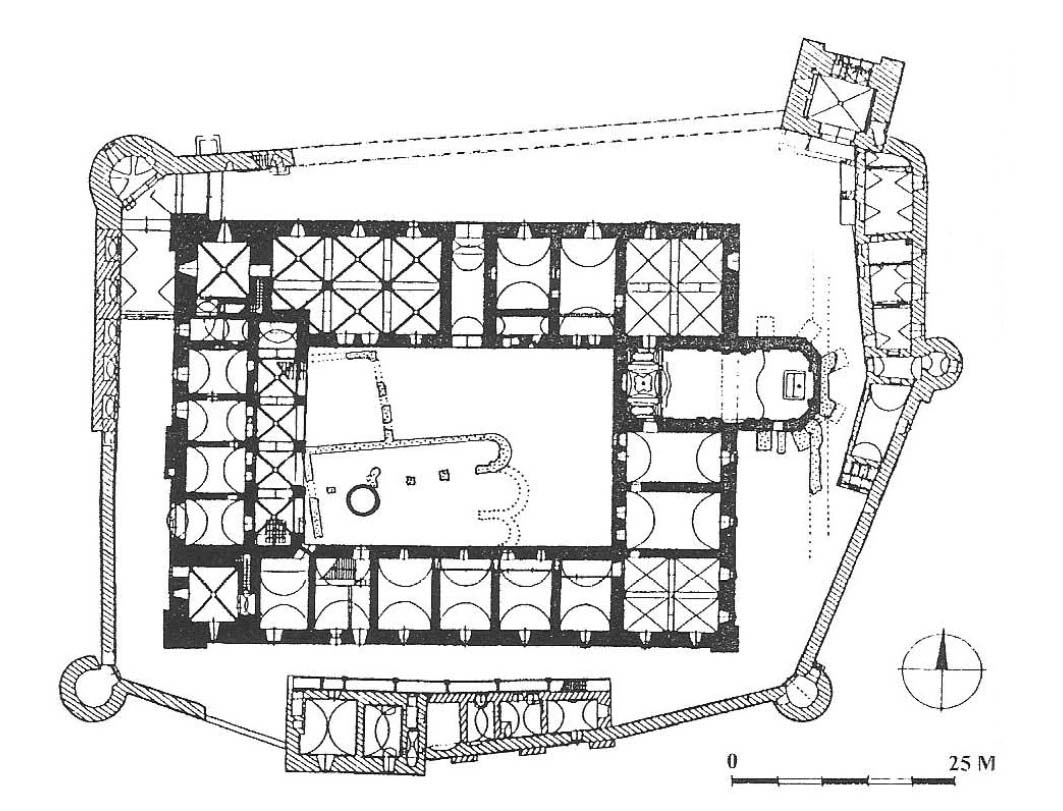

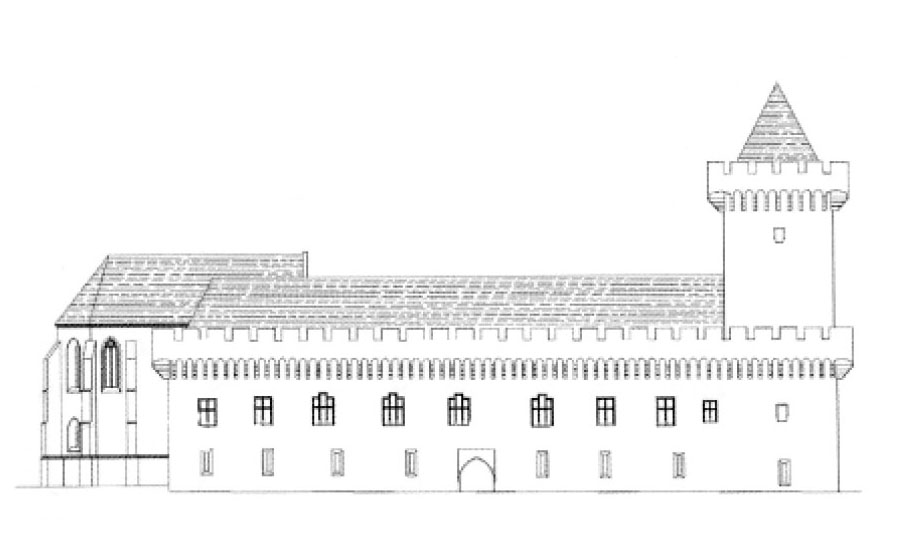

The castle was located on a flattened hill, between the Slatina River in the south and the Hron River in the west. In this place there was originally a Romanesque basilica of St. Nicholas, completely demolished during construction works on the castle. The secular building consisted of four one-story wings, forming a rectangle with a closed courtyard in the middle. Inspiration for its construction is seen in the northern Italian representative town castles. Most of the building was occupied by residential and representative rooms, crowned at the top with gable roofs. Defensive fortifications were limited to two quadrilateral towers in the west range, located closer to ferry on the river. Perhaps like the Italian or French castles it were crowned with machicolation on protruding corbels. On the opposite side, the castle chapel protruded from the regular layout, with its chancel protruding in front of the eastern wing.

At the end of the fifteenth or in the first half of the sixteenth century, the castle received a new ring of walls with four towers and a gatehouse. The shape of this fortifications was similar to a rectangle which southern and eastern sides slightly rounded. Round and half-round towers were built on the three corners, and at the fourth, north-east, a gate was located, which was housed in a two-story, square tower, far exceeding the remaining towers. An additional semicircular tower was placed in the middle of the eastern curtain. Behind the gate, on the right, a small courtyard stretched out, from which through the next gate led the entrance to the palace part. Next to the gate, to the inside of the wall was the guard building, reinforced with already mentioned semicircular tower. On the opposite side of the castle, by the southern wall, there was a captain’s house, intended for the commander of the military district.

The four wings of the castle formed a closed courtyard, which was entered through a gate in the northern wing. The ground floor of the castle housed utility rooms and apartments for servants, while the first floor was intended for the king and the court. The entire northern part, widest of all wings, was used for representative purposes. On the ground floor there was, among others, a large Knight’s Hall, with a vault supported by two pillars, as well as a smaller, square-shaped hall in the east, also topped with a cross-rib vault. There was also a gate passage with sedilia on the sides, facing the town. The rooms on the first floor of the northern wing were covered with wooden ceilings, except for the vaulted royal chamber. It was adjacent to and connected to the eastern wing of the castle, where the chapel was located. The interior layout of the west wing was designed in a unique way. It consisted of two routs, the inner one of which had a row of vaulted arcades.

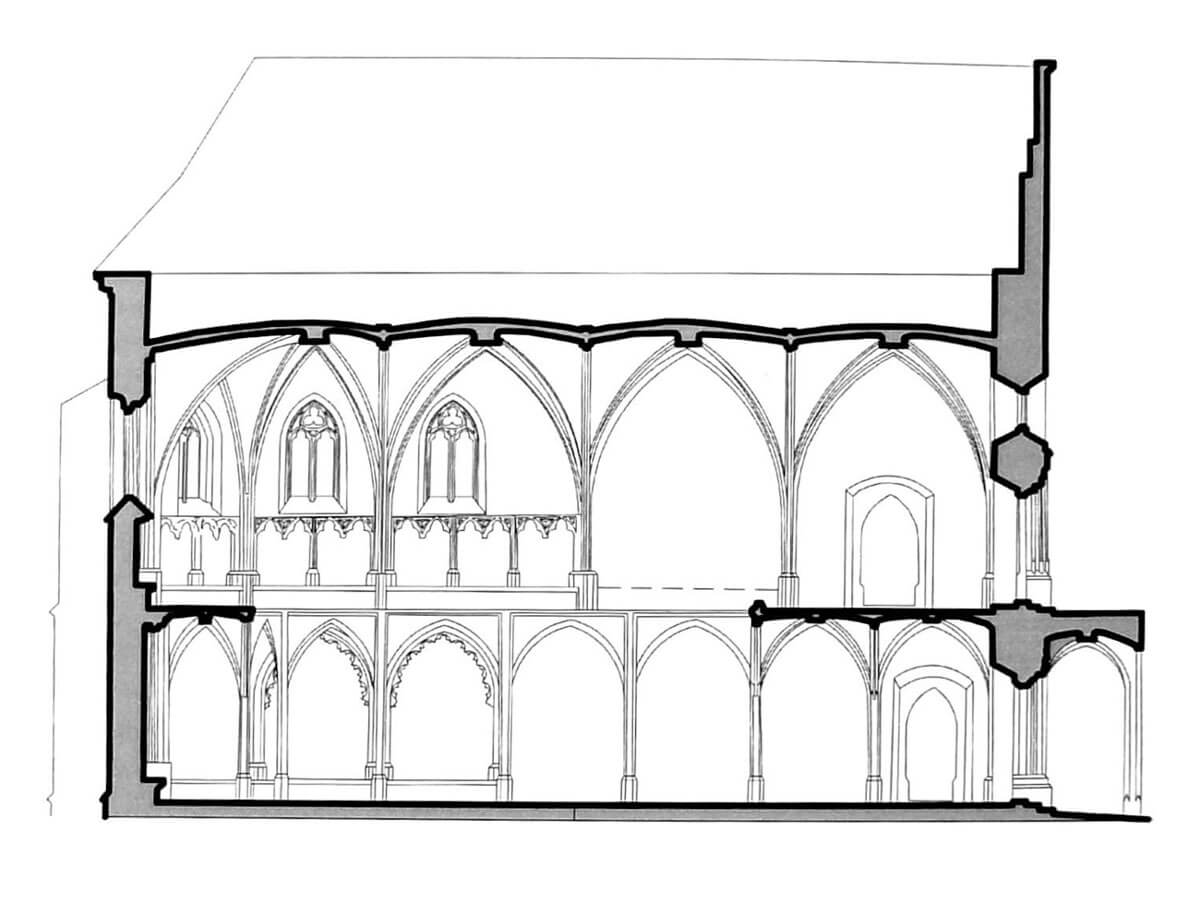

The presbytery apse of the chapel protruded in front of the walls. Its interior was divided into two levels: the upper one for the king and the court and the lower one for the servants. Originally, the chapel was topped with a cross-rib vault, and its side walls had a number of seats in the lower part of the upper floor. From the first floor, through the cloister in the courtyard (and, as already mentioned, from the king’s chamber), it was possible to get to the gallery on the western side of the chapel, which then turned into a balcony surrounding the entire first floor. The floors of the chapel were probably connected by an opening in the vault.

The lighting of the four wings of the castle was provided by large rectangular windows at the level of the floor, pierced both from the side of the courtyard and in external elevations. The royal chamber, illuminated by six-light windows, derived from the architecture of the Czech castles of Charles IV (Karlštejn, Prague), received special treatment. At the ground floor, only narrow slit openings of a defensive character were used. From the side of the courtyard, some of the rooms were also illuminated by ogival windows closed at the top with trefoils. At the height of the first floor, the courtyard was surrounded by a wooden, Gothic gallery with entrances to individual rooms. During the late Gothic rebuilding, new saddle-shaped portals with rich painting decorations were used in the grund floors.

Current state

Today, the castle is divided into the inner palace part of the fourteenth-century origin, but rebuilt in later centuries, and the sixteenth-century outer fortifications. The original structure lost its Gothic western towers, the form of the roofs was changed, and there are now rounded turrets in the corners. The castle chapel was significantly transformed and unfortunately most of it lost original Gothic character. Currently, the administrator of the castle premises is the Slovak National Gallery, which displays valuable exhibitions. The permanent exhibition includes replicas of valuable timber sculptures of Master Paul of Levoca, a collection of Gothic wall paintings and a selection of works of European fine arts, entitled Ancient European art. In the summer, a theater festival takes place in the courtyard. The castle interiors are open to visitors from Wednesday to Sunday between 10.00 – 17.30 but the last entrance is at 16.45.

bibliography:

Bóna M., Stredoveké hrady na strednom Pohroní, Nitra 2021.

Bóna M., Plaček M., Encyklopedie slovenských hradů, Praha 2007.

Stredoveké hrady na Slovensku. Život, kultúra, spoločnosť, red. D.Dvořáková, Bratislava 2017.

Wasielewski A., Zamki i zamczyska Słowacji, Białystok 2008.