History

Zvolen Castle (Hungarian Zólyom, Polish Zwoleń, German Sohl, Latin Zolum, Zolium), called the Old Castle from the end of the 14th century to distinguish it from the newer castle located in the town, was founded on a hill that was already inhabited in the Stone Age and then in the era of the Lusatian and Piliny cultures in the Bronze Age. The beginnings of the early medieval castle, or in fact still a hillfort, could be related to the establishment of a county by the Hungarians, headed by a royal official, a zupan (ispán). This county was founded at the beginning of the 12th century by King Coloman, after the fall of the independent principality of Nitra. At the latest, the fortifications of the castle could have been built in the times of Bela III at the end of the 12th century. Perhaps the work of King Andrew II was the lower part of the castle, where he lived during his visits to Zvolen, so as not to occupy the upper castle of the zupans. The first record of the name Zvolen dates back to 1214. In 1222, the Zvolen zupan Detrich was mentioned, to whom, seven years later, the ruler gave extensive lands from the royal estate of the Zvolen county.

During the great Mongol invasion of 1241, it is possible that the invaders also reached Zvolen, because two years later King Bela IV renewed the town’s lost privileges. Traces of conflagration discovered on the hill would lead to the assumption that the fights were also in the castle, although it is not known with what effect. Fears of the return of the Mongols prompted the king to seek allies and improve relations with his neighbors. Bela IV invited to Zvolen the prince of Halych, Daniel, and the metropolitan of Kiev, Cyril. In 1247, the wedding of Lev, Daniel’s son, and Bela’s daughter, Konstancja, also took place in Zvolen. On this occasion, the Hungarian knights captured in previous battles were released and a truce was concluded between the rulers. The castle, being a suitable place for such important event, had undergone a significant expansion by that time. Master stonemason Bertold participated in these works, to whom in 1255 the ruler granted the estate of Dubová, as payment, cut from the estates of the Zvolen castle.

During the reign of Ladislaus IV of Hungary, the monarchical power weakened and the influence of some noble families increased. At that time, the zupan of Zvolen was a certain Demeter, son of Mikuláš, who illegally minted a poor-quality coin in the castle, imitating the coins of the rulers of Hungary and Austria at that time. In addition, the castle was the object of attacks, for which the Turčian and Liptov knights became famous. In 1290, after the anarchy in the country was appeased, eight of them were rewarded by the new Hungarian king Andrew II. Lampert from the powerful Hunt-Poznan family, who had a dispute with Demeter over the Modrý Kameň (Kékkő) castle, could have been involved in the attacks.

At the beginning of the 14th century, the period of interregnum after the extinction of the Arpad dynasty was used by the Zvolen zupans to strengthen their position and become independent. For this reason, in 1306, the army of Charles Robert of the Anjou dynasty seized the castles of Zvolen, Ľupča, Dobrá Niva and Plachtince, previously controlled by Demeter and his nephew Donch. Soon, however, the surrounding lands came under the rule of Máté Csák (Matúš III Čák), a magnate competing with the king himself. After a few years, the victory in the civil war between Csák and the king began to tip in favor of Charles Robert. Donch’s turn to the royal side around 1314 completely changed the balance of power, accelerated the collapse of Csák’s dominion, and opened the way for Donch to a great career, crowned with the status of the second most important person in the kingdom. Although he built several castles, Zvolen remained his most important seat.

In the fourteenth century, the character of the castle changed. The development of mining of precious metals led to the creation of new trade routes, two of which crossed at the foot of the castle, giving protection to merchants and carts with silver and copper. At the end of the 1430s, the vast territory of the county was divided into smaller territorial units, and only the nearest estates began to be subject to the castle itself. Around the same time, Zvolen became the residence of the Hungarian kings, used by them during hunting in the nearby forests. When in the second half of the 14th century, Louis the Great ordered a new, more comfortable castle to be built in Zvolen, the importance of the old seat began to decline. At the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the castle on the hill served only military purposes.

During the fights for the Hungarian throne in the mid-15th century, Zvolen remained in the hands of John Jiskra of Brandýs, acting on behalf of Queen Elizabeth and Ladislaus the Posthumous. In a short time, Jiskra captured several castles and towns in Upper Hungary, but the castles of Zvolen remained one of its main points of support. In 1447, the regent of the kingdom, János Hunyady, gave Zvolen to the Polish knight Piotr of Jarochowo as a reward for his participation in military expeditions, especially during the siege of the Starý Zvolen castle, where Peter fought “not without bloodshed”. During these fights, the upper castle probably burned down, it could also have been destroyed in 1451, when Hunyady burned Zvolen. Opposite the castle, he was to build his own fortifications, which he used to disturb Jiskra until he forced him to negotiate a peace. However, it is not known whether these fights concerned the castle in the town or an older building. Similarly, it is not known which castle the appointment in 1465 and 1467 of two castellans of Zvolen and two captains concerned. It is possible that both castellans already had office in the town in one castle (similarly to Vígľaš), while the stronghold on the hill, devastated during the fights, meaningless in times of calmer situation in the region under the reign of Matthias Corvinus and was abandoned in the second half of the 15th century. The ruins came to life only briefly in the 16th century, when a wooden observation tower was erected on the top of the hill, which was part of the anti-Turkish defense system.

Architecture

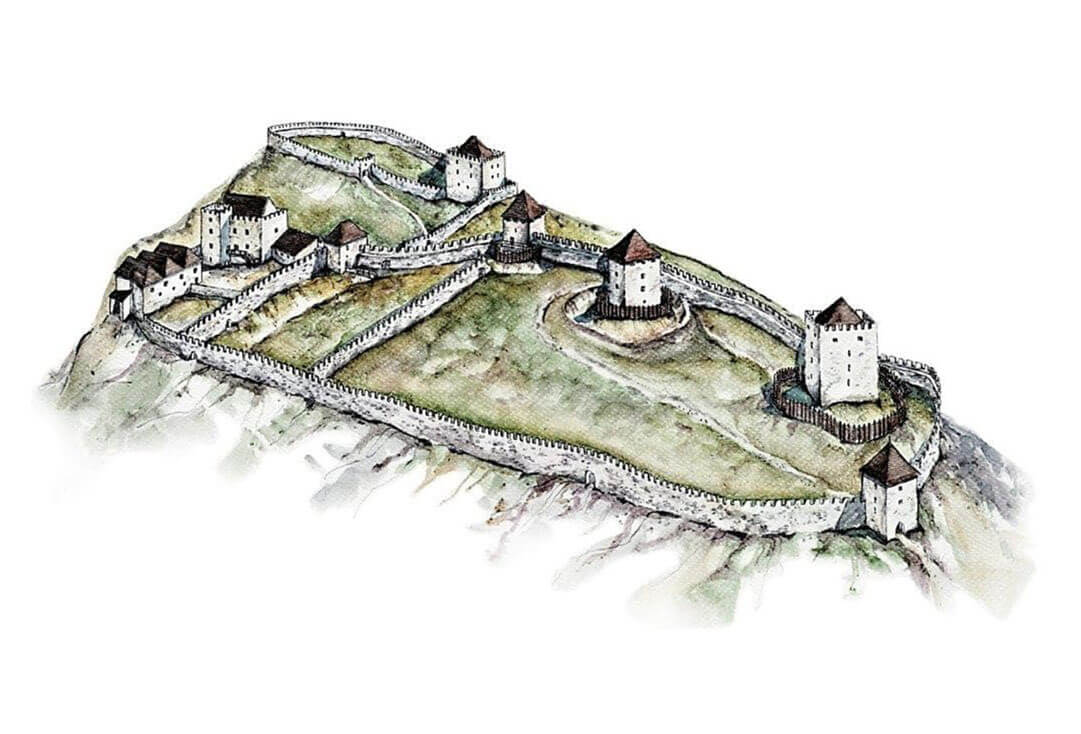

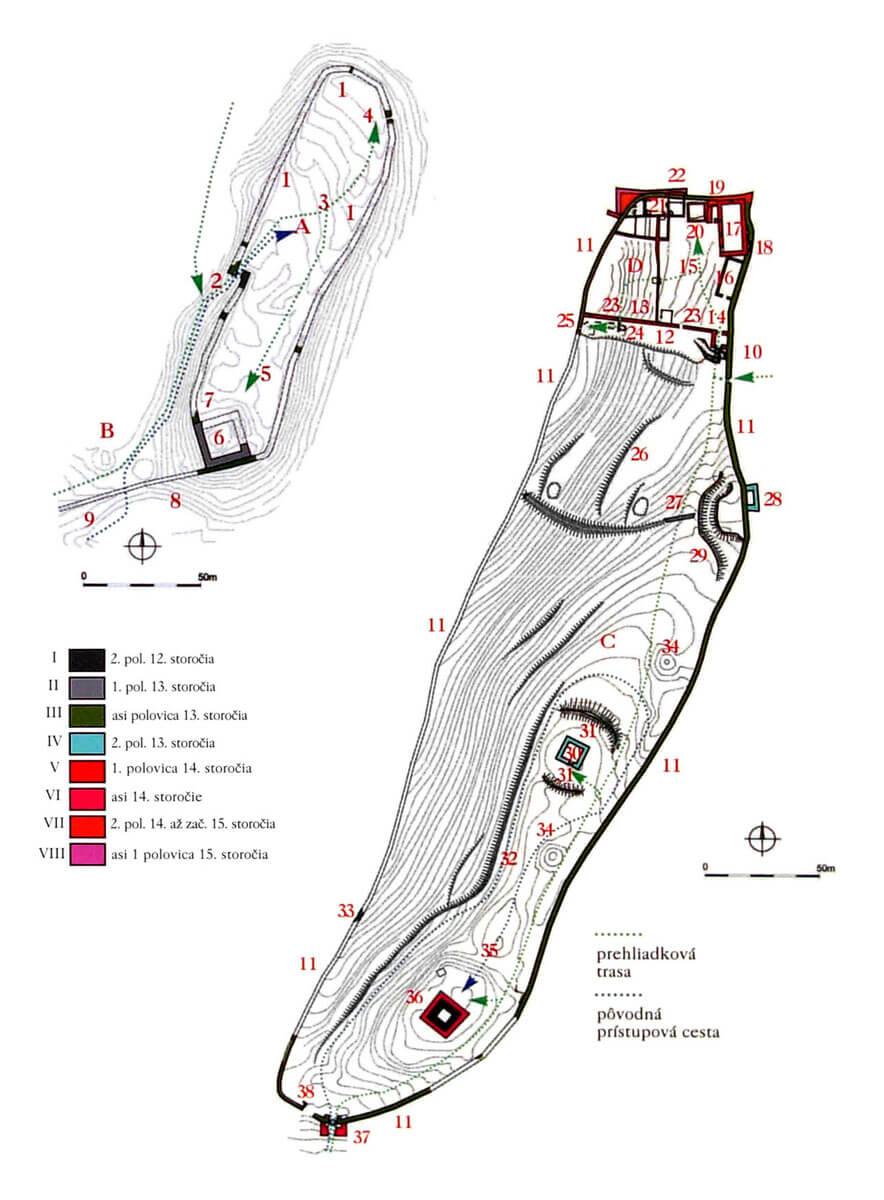

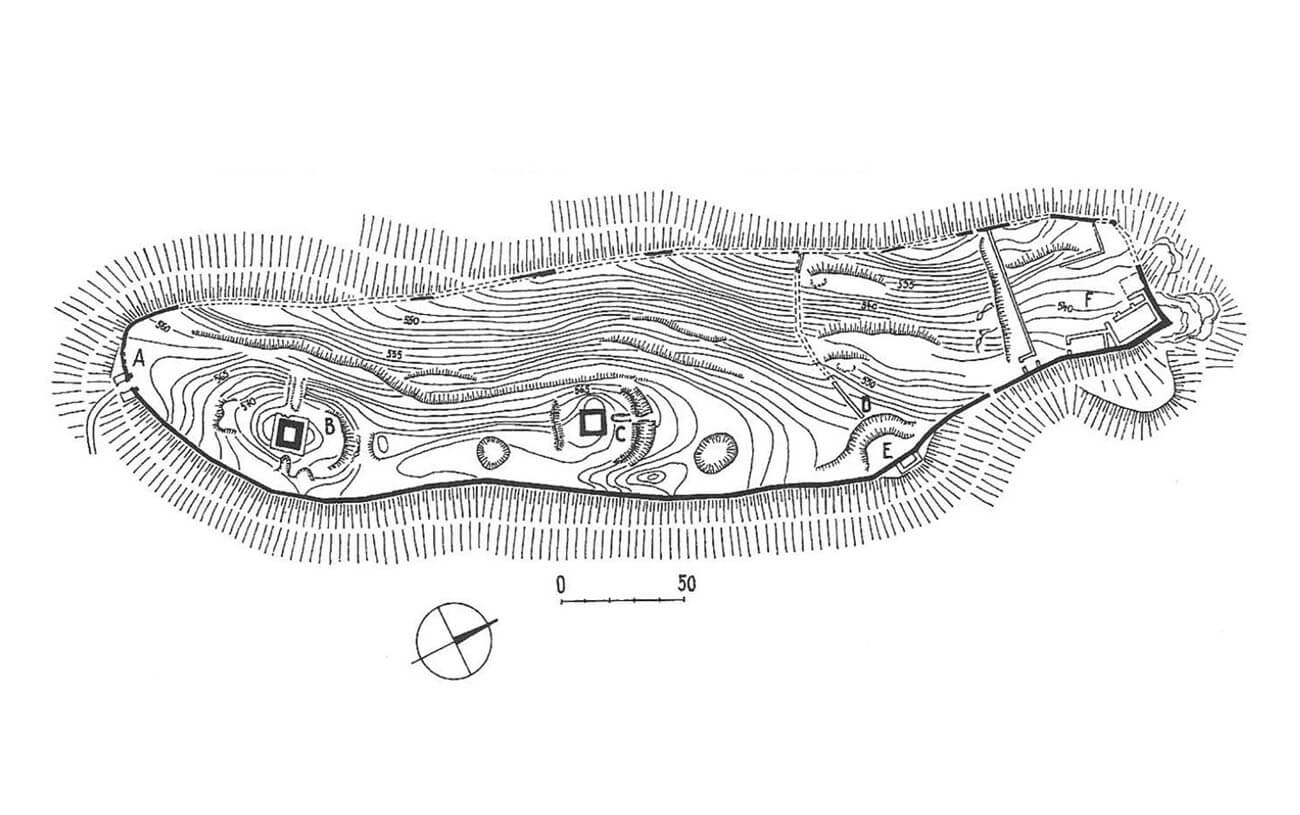

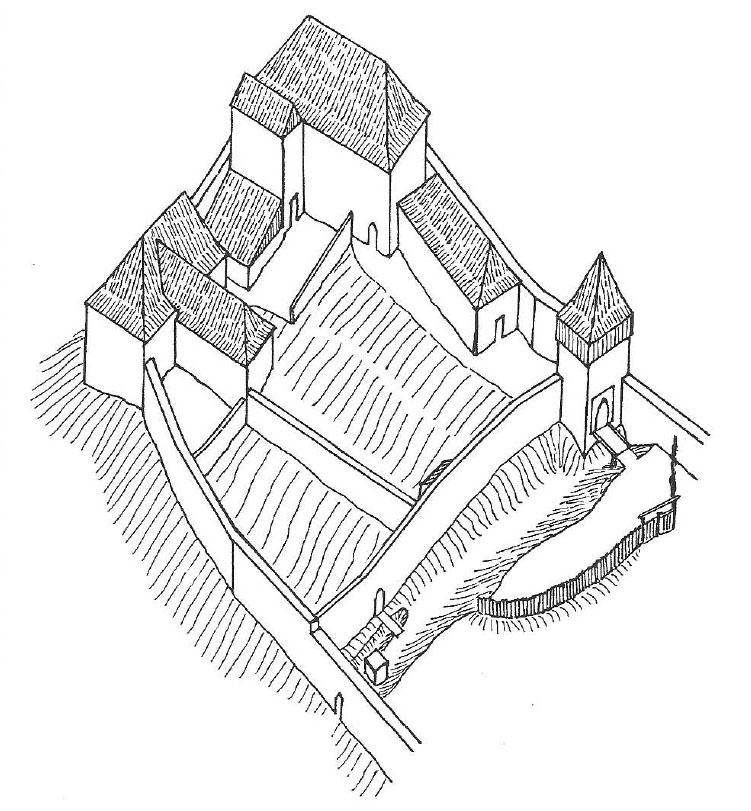

The castle was founded on a vast, elongated south-west, north-east hill, covering an area of about 3.6 ha and towering 571 meters above sea level over the valley of the river Hron (together with the lower castle, the entire complex occupied as much as 4.7 ha). On the north-eastern side of the castle, at the confluence of the Slatina River with Hron, a settlement developed, and then the town of Zvolen. From the north-west, the steep slopes of the castle hill descended into a narrow valley with the Hron riverbed, while from the other sides ravines separated the hill from the rest of the Vepor Mountains massif.

The oldest stone part of the castle from the 12th century was located in the southern, highest part of the hill. It was a large residential and defensive tower with dimensions of 10.8 x 11.7 meters and wall thickness of up to 3 meters, initially probably surrounded by wooden fortifications protecting the then small space of the castle. The expansion that took place at the beginning of the 13th century made the castle a huge, two-part complex. At the ends of the hill, two fortified refuges, i.e. shelters for people, were created, later called the upper and lower castle, with the fortifications of the upper castle partly erected on the ramparts of the Bronze Age hillfort. Over time, the refuges were connected by a single line of the wall, and the very long courtyard of the upper castle was separated by transverse fortifications.

The perimeter walls of the upper castle from the mid-thirteenth century surrounded a vast area measuring approximately 430 x 90 meters without sharp corners. It were 2 meters thick and about 6 meters high. The entrance to the upper castle was in the southern part, in the place where the wall was the shortest. A gatehouse, opened from the side of the courtyard, was erected there, which exceeded the crown of the perimeter wall. Its passage was closed with a massive door blocked with a bar. Due to the large scale of the castle, in addition to the main gate, smaller posterns leading to the steep slopes of the castle hill were also created in the walls.

Located in the north-east, the lower castle had the shape of an elongated oval measuring 183 x 38 meters. In its extreme part, on a gentle slope, a very large, four-sided building was erected at the beginning of the 13th century, which was a residential tower (donjon) or a tower-like palace. It was situated almost 100 meters lower than the tower of the upper castle, and after the perimeter of the walls of the lower castle was built in the mid-thirteenth century, it did not take place in its center, but on the south-western edge of the lower castle, right at the entrance. The tower was connected to the walls surrounding the courtyard in two corners, and from the third corner ran the above-mentioned single line of the wall, climbing the slopes of the hill towards the upper castle. This wall reached a length of about 350 meters, but perhaps its western end was never completed and it ended in front of the ditch of the upper castle. Under the tower of the lower castle, the last section of the access road crossed, where the first, outer gate must have been located.

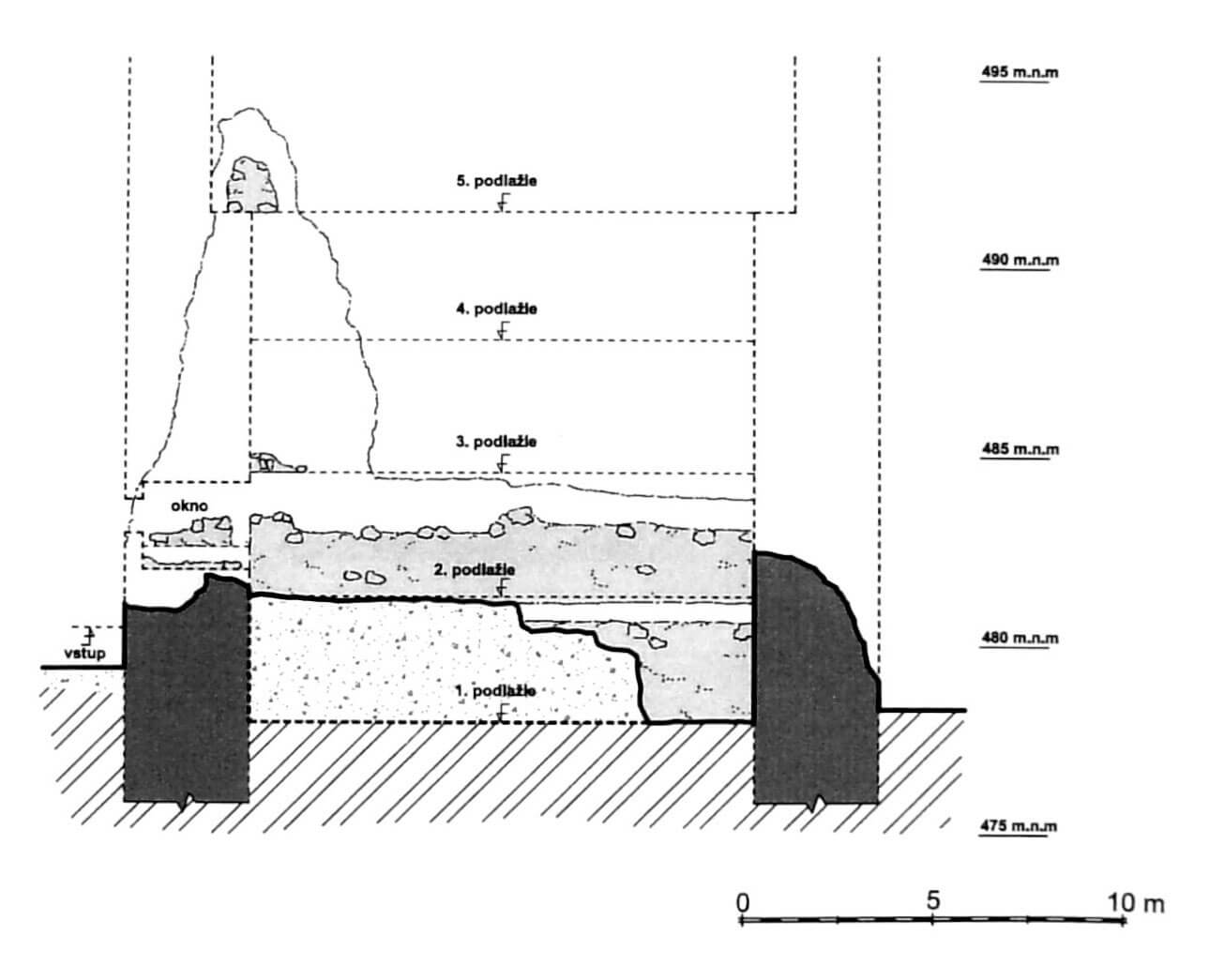

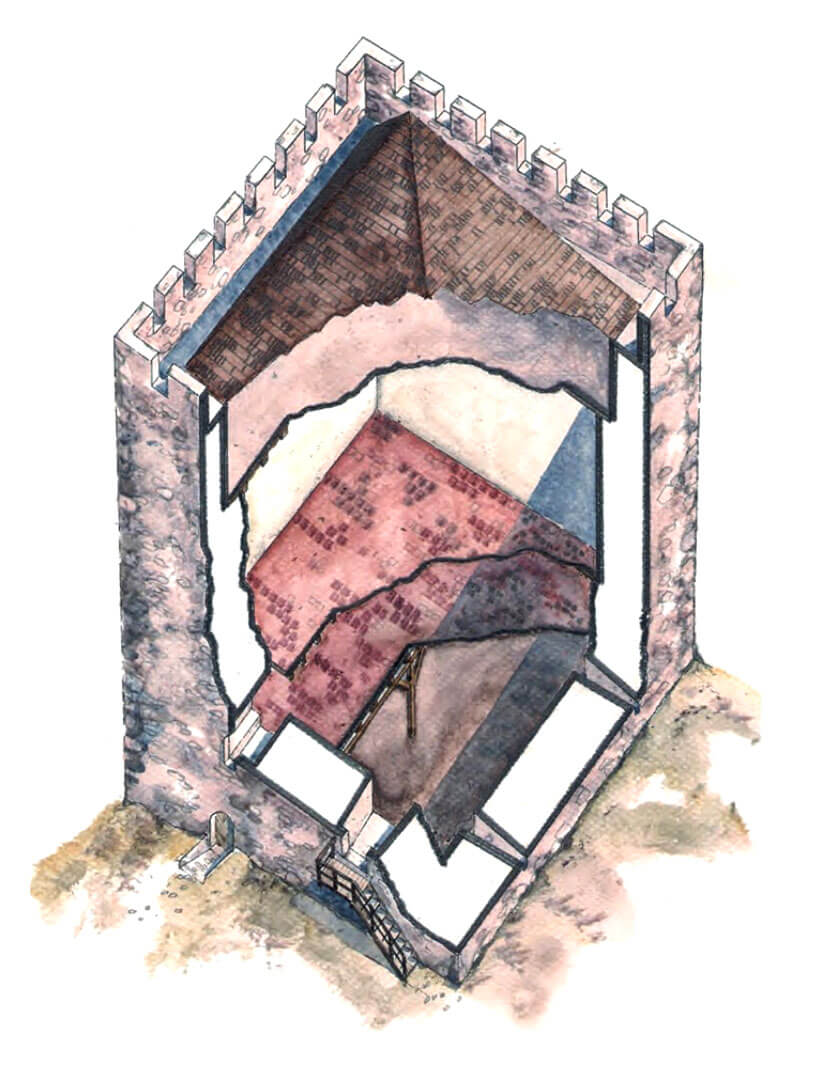

The tower of the lower castle was built of erratic stones, laid in regular layers and reinforced in the corners with ashlar. The external facades of the building were modified with mortar, smoothed to the faces of individual stones. The tower had dimensions of 19.9 x 19.9 meters in plan and the thickness of the walls in the ground floor was 3.3 meters, which gave an internal space of 13.3 x 13.3 meters. The height probably reached at least 20 meters. In addition to the utility ground floor, the tower probably had four more residential floors separated by wooden ceilings, with the lowest floor, due to its largest dimensions, supported by a central timber pillar. The ground had a floor made of flat stones and compacted clay. It had an entrance portal leading from the courtyard, but an independent entrance led to the first floor, probably via a ladder or external stairs. The upper floors, unlike the lowest floor, were illuminated by larger windows with sedilia.

The walls surrounding the courtyard of the lower castle were extremely massive, 2.5 meters thick, and therefore slightly thicker even than the fortifications of the upper castle. Unlike the upper castle, they were led by straight, shorter sections with not rounded bends. The height of the curtains was not significant, because already at the height of 2.5-3 meters there was an offset on which the guard’s wall-walk functioned. Another 1.5-2.5 meters high had to have parapet, which gave a total height of the wall of 5-6 meters. The gate was a portal 2.8 meters wide, closed from the inside with double-leaf doors. Its jamb was made of carefully prepared ashlar, with a chamfer ended with rounded moulding, characteristic of the second half of the 13th century. It was placed in the western part of the perimeter, in a bend formed by two curtains, creating a very short passage, only 1.5 meters long, perhaps vaulted. In addition, in the lower castle there was a smaller postern, 1.2 meters wide, set in the north-eastern part of the complex.

Before the end of the 13th century, in the central part of the upper castle, a second square tower was erected, which was named Pertold’s Tower after the name of the builder. It had external dimensions of 11 x 11.2 meters, with an interior size of 7 x 7 meters. With such large dimensions, it certainly served residential functions in addition to defensive ones. In the fourteenth century, its original entrance in the ground floor was walled up, and a new entrance portal was created on the first floor. In addition, in the eastern part of the upper castle, an early Gothic tower was erected, which may have housed the royal mint. Its role was also to secure communication with the lower castle. It was added to the perimeter wall from the outside, and on the side of the courtyard from the tower there was a transverse defensive wall separating the northern part of the upper castle.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the massive structure of the oldest southern tower of the upper castle was additionally thickened by another 2 meters, reaching as much as 5 meters in the ground floor of the perimeter wall, and dimensions of about 15 x 16 meters. Probably the reason for the reconstruction was the lack of living space and the desire to raise the structure by an additional one or two floors (if it was for purely defensive reasons, the walls would probably be strengthened from the inside). In addition, the southern gatehouse was rebuilt, extended in the fourteenth century from the front (outer) side. In the new part of the passage, in front of the older doors, a portcullis was inserted, which had to be operated in one of the three upper floors. The first floor was the guard’s room above the passage. The second floor was connected to the wall-walk. From the side of the courtyard, it was equipped with an overhang and roofed wooden porch.

Inadequate living conditions in the narrow towers were the reason for another large expansion of the castle from the beginning of the 14th century, when the Zvolen knights Demeter and Donch were the zupans. At that time, the expansion of the older buildings was completely abandoned, and instead in the northern, slightly lower part of the upper castle, behind the second transverse wall and the ditch, a new residential and defensive complex was created, occupying an area of about 50 x 50 meters. The entrance to it led through a four-sided gatehouse at the junction of the perimeter and transverse walls. The complex consisted of at least three residential and economic buildings. They were attached to the perimeter wall so as not to interfere with the communication of the wall-walk.

The main palace measuring 20 x 8 meters was located in the north-eastern corner. It had a utility and storage ground floor and two upper residential floors. The lowest storey was poorly lit by high-placed narrow windows, over which a beamed ceiling was placed. The upper floors could already have larger windows with side seats. On the eastern side, a small annex was placed in front of the defensive wall and the side facade of the palace. According to the orientation, it is possible that there was a chapel in its upper floors.

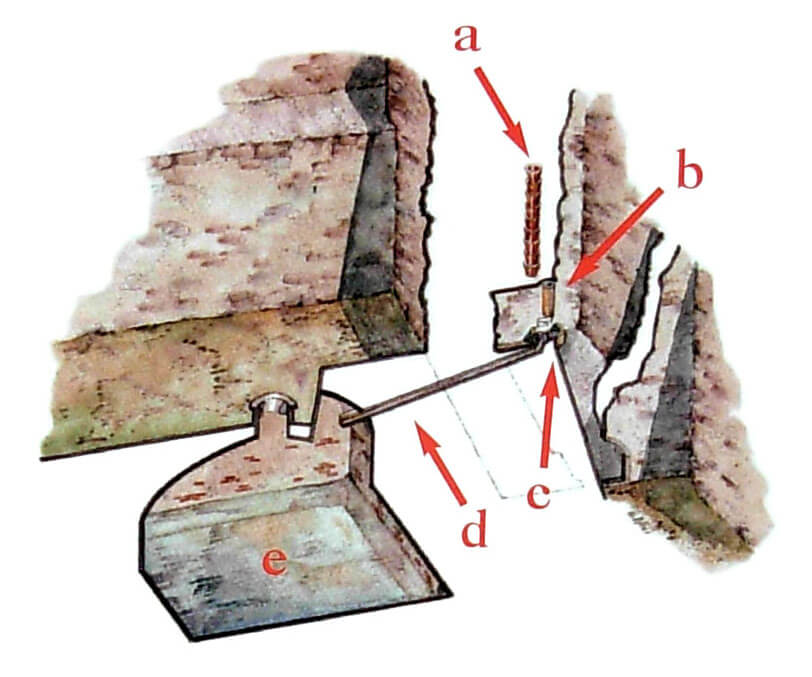

In the vicinity of the palace, a huge, brick rainwater tank was placed, measuring 6.6 x 6.8 meters and at least 10 meters deep, over which a smaller wing of the palace was added to the northern wall. An annex located next to it contained a filter stone vessel through which water flowed into the tank. Water circulation was ensured by a ceramic pipe running through the thickness of the wall and a vertical wooden pipe attached to the wall from the inside. The water filtered through the vessel flowed into a tank whose sides were covered with high-quality smooth plaster and the upper part was covered with a vault. In addition, in the wing of the palace in the ground floor there were stoves that heated the lower parts of the building.

Increasing residential requirements in the second half of the 14th and early 15th centuries required the erection of additional buildings. There was no room for them near the wall, so part of the old fortifications in the corner was demolished and the new corner of the building was extended in front of the original perimeter. In addition to gaining space, the builders were prompted by an attempt to create at least a partly regular courtyard, flanked by two wings of palace buildings, perhaps imitating Gothic residences such as the castle in the town under the hill. In the fifteenth century, the fortifications of the entire upper castle were outdated. Presumably in connection with an attempt to quickly improve the defense capabilities, in the times of Jiskra, the 13th-century towers were surrounded by earth ramparts, probably topped with some form of wooden fortifications.

Current state

The lower parts of the perimeter walls of the upper castle, relics of two square towers, remains of 14th/15th century residential buildings in the northern part of the complex, as well as sections of walls and transverse ditches that divided the courtyard have survived to this day. Fragments of the walls are 3 meters high, but in the northern corner of the castle the wall has been preserved up to the level of the wall-walk. The southern gate of the upper castle has survived in the best condition, one wall of which has been preserved in full height. In the lower castle, you can see the relics of the perimeter walls along with the lower parts of the jambs of the gate portal. The parts of the southern and western walls of the tower house of the lower castle are higher, reaching in one corner up to 9 meters in height. Almost the entire ground floor has been preserved, accessible directly from the courtyard through the portal.

Despite the relatively modest state of preservation, the Old Castle has a layout that is legible to this day, which is a unique solution, one of the few in which two quite distant strongholds were combined into one defense system. The exceptionally large dimensions of the oldest residential tower of the upper castle and the tower of the lower castle, as well as very massive perimeter walls, make Zvolen one of the largest castles in Slovakia (after Nitra, Devín and Bratislava).

bibliography:

Beljak J., Beljak-Pažinová N., Šimkovic M., Pusty hrad vo Zvolene a opevnenia v jeho okolí, Zvolen 2015.

Beljak J., Beljak-Pažinová N., Beláček B., Golis M., Hunka J., Krištín A., Kohút V., Maliniak P., Mordovin M., Przybyła M., Repka D., Slámová M., Šimkovic M., Tóth B., Žaár O., Pustý hrad vo Zvolene. Dolný hrad 2009-2014, Zvolen-Nitra 2014.

Beljak J., Maliniak P., Šimkovic M., Zvolenský Pustý hrad, Zvolen 2011.

Bóna M., Stredoveké hrady na strednom Pohroní, Nitra 2021.

Bóna M., Plaček M., Encyklopedie slovenských hradů, Praha 2007.

Wasielewski A., Zamki i zamczyska Słowacji, Białystok 2008.