History

The Spiš provostship was founded around the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries. From the beginning of its existence, it belonged to the Archbishopric of Esztergom, which was founded by the Hungarian king Stephen I. Probably the establishment of the provostship was also a royal initiative, related to Bela III, Emeric or Andrew II, rulers of the turn of the centuries. It certainly happened before 1209, when the first provost, who headed the congregation of clerics (chapter), was recorded in documents. The great role of Andrew II was indicated by the document of King Bela IV from 1249, which mentioned the donation of the Jablonov estate (terra Almas) to the provost by his father. In the process of creating the chapter and its buildings, the younger brother of King Bela IV, Coloman, could also play a role, who in the early 13th century was in possession of the Spiš estate. After 1226, however, his influence in the region weakened, as he received Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia from his father, Andrew II.

The construction of the chapter church of St. Martin began in the early 13th century, on the site of an older church from the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries, and was completed in the years 1245-1275, after the Mongol invasions stopped and the damages were removed. In the will of provost Muthmerius (Mutimír) from 1273, it was recorded that he donated money to complete the construction of one of the towers. The first palatial residential building of provosts was also built from his foundation. A year later, in 1274, the existence of a canonry was recorded, residential buildings of the canons of the chapter, adjacent to the church of St. Martin. Already in 1286, it were thoroughly renovated for the first time, which was confirmed by the document of the Archbishop of Esztergom, settling the dispute between the provost and the canons.

In the years 1288 – 1289, the devastation of the chapter complex was caused by the invasion of Cumans of King Ladislaus IV. They plundered the church, broke into the sacristy, which also served as an archive and treasury, destroyed documents and stole the seal of the chapter. It was probably this invasion that affected the decision to build a stone wall around the church of St. Martin and neighboring buildings. Additional works on the church extension was carried out in the next century, when, among other things, a sacristy and two chapels were added and new living quarters for canons were erected, but in general, the fourteenth century was characterized by much less construction works.

In 1433, during the Hussite invasion of Spiš, the church was set on fire and severely devastated. Since that event, it stood in ruins until the second half of the 15th century, which could have been related to the suspension of church life due to the occupation of the Spiš Castle by Jan Jiskra mercenaries in the years 1443-1455. Only in the years 1462-1478, on the initiative of the provost Ján Stock, church was rebuilt. A new Gothic chancel was built, consecrated for Gašpar Back in 1478. Then, in the years 1488-1493, the nave was transformed and the tomb chapel of the Zápolya family was added from the south. Late Gothic construction works were also carried out at the residential buildings of the canons and provost.

In the 16th century, the building activity of the chapter entered a period of stagnation, caused by the progress of the Reformation, which spread rapidly in Spiš from the 1540s. For provosts, it meant a reduced number of congregation and a loss of part of their income. In addition, the situation was complicated by problems with the right of patronage usurped by noble families, armed attacks, natural disasters and the unworthy actions of provost Horvát, who in 1536 appropriated funds for the renovation of the palace, and in 1544 plundered the furnishings of the palace and the church at the time of his resignation ex officio (he even ordered all windows, doors, floorboards and shingles from the roof to be taken to his Dunajec Castle). Other provosts, Stanislav Várali, Blažej z Petrovaradín, Peter Pavlinus and Juraj Bornemisa, struggled with huge financial problems, but above all religious ones. The most necessary repairs and additions to the equipment were carried out for provost Martin Pete, and the church itself was repaired in the Renaissance style (attics and cupolas of the towers) in 1591. In addition, the defensive walls around the church were renovated and a gatehouse was built.

In the 17th century, numerous turmoils of war and anti-Habsburg uprisings swept through Hungary. Therefore, the most important construction activity of the chapter were the fortifications around the canons’ residential buildings at the beginning of the second half of that century, adapted to the use of firearms, but built in the medieval wall-tower system. The reconstruction also affected the church of St. Martin, which northern sacristy was transformed in 1706, as well as residential buildings of canons, modernized in the Baroque style. In 1776, with the creation of the Spiš bishopric, the church of St. Martin was raised to the cathedral and, together with the surrounding buildings, underwent numerous late-Baroque alterations (e.g. the ground floor of the gallery, stairs to the northern tower). Unfortunately, it was associated with numerous demolitions of medieval buildings (rotunda of St. Andrew, the chapel of St. Valentine, most of the defensive wall). Some of the early modern modifications to the church were removed during repairs in the years 1873-1889.

Architecture

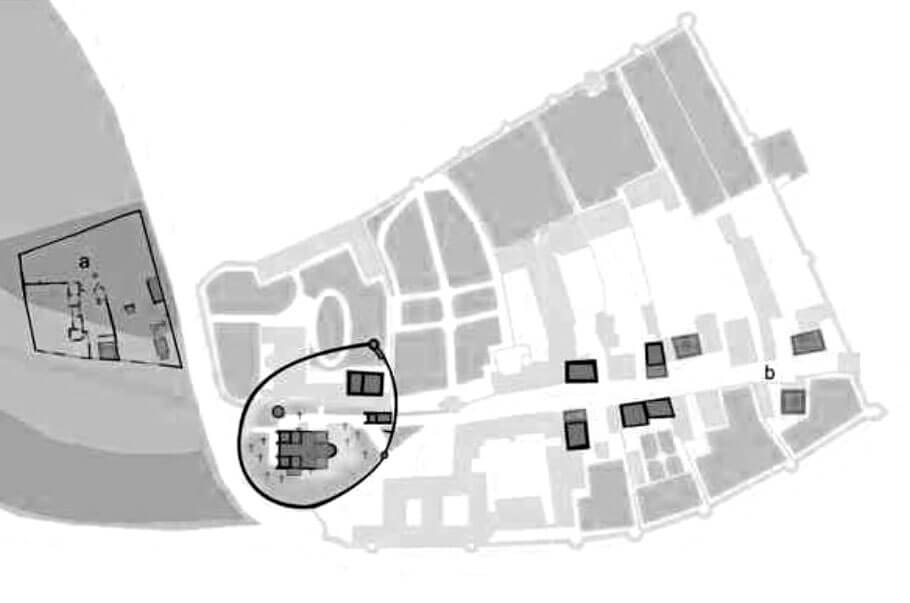

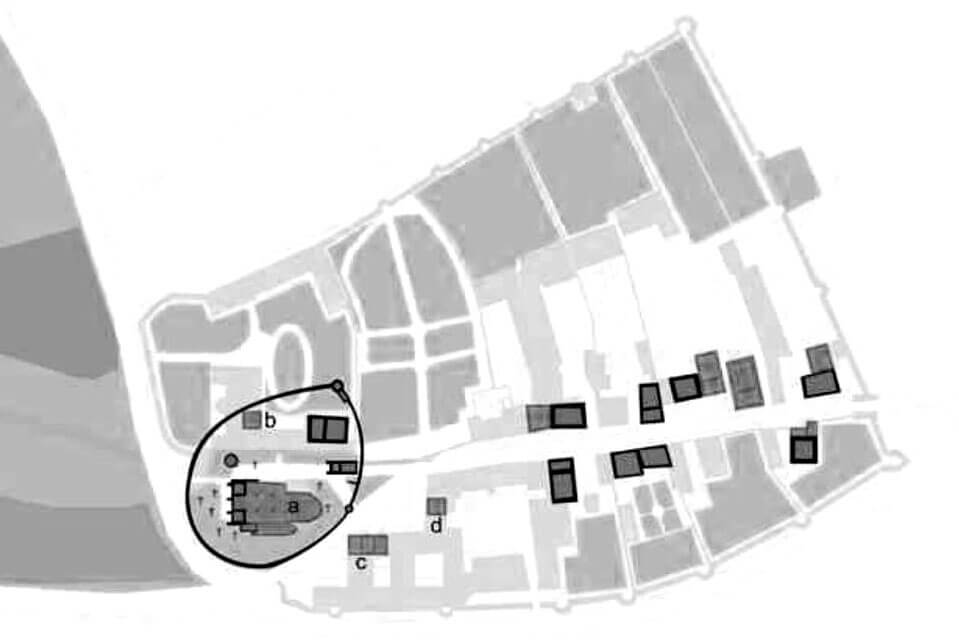

Church of St. Martin, along with the neighboring buildings of the chapter, were erected on a low hill called Mons Sancti Martini, located in the Hornad Basin, opposite the Spiš Castle. The slopes of the hill were closest to the church on the south side, where it were also the steepest. To the north-west, the area slightly and gently rose to the top of the hill, where the oldest residential and representative buildings of the chapter were located. In the north and north-east, the slopes sloped gently towards the lowland part of the basin, while in the east there were canons buildings, and at the foot of the hill a settlement of German settlers grew up (Slovak Spišské Podhradie, German Kirchdorf, Hungarian Szepesváralja).

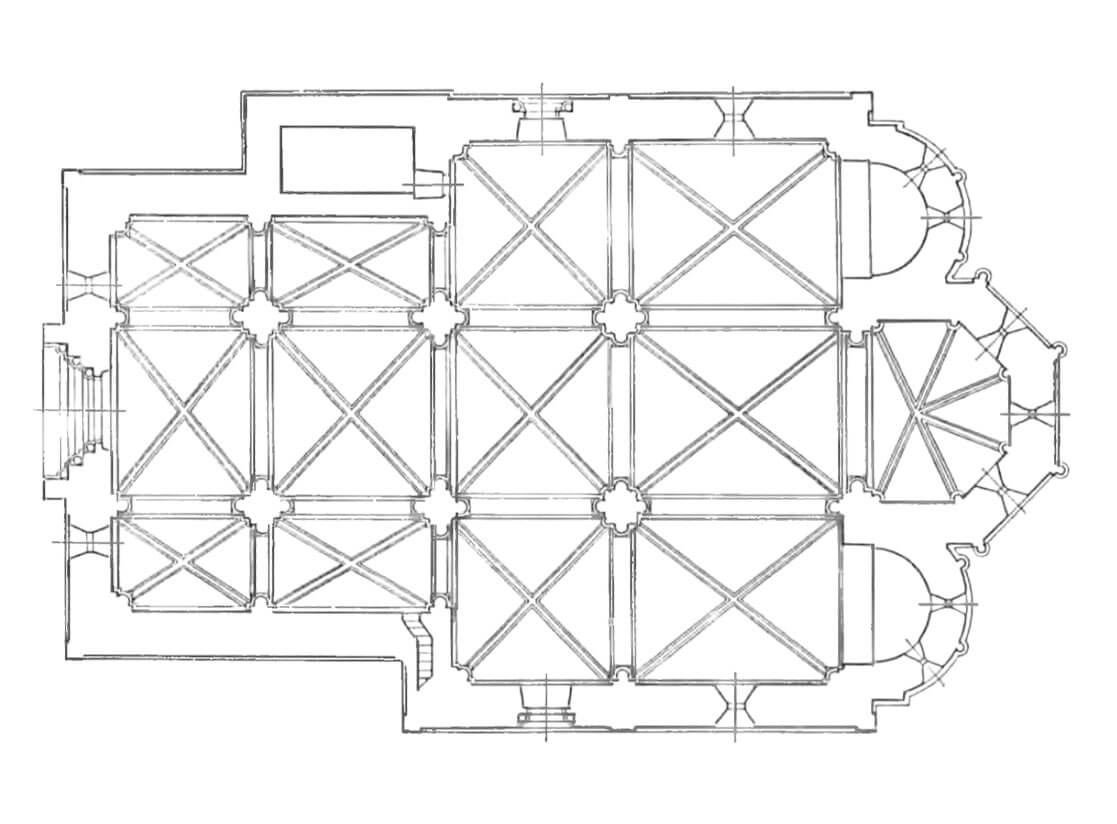

The Romanesque chapter church was erected on the site of an older, smaller, aisleless temple. Originally, it was a pseudo-basilica with central nave and two aisles, with two towers on the west side, a transept slightly wider than the nave and a single-bay chancel ended with a semicircular apse (perhaps the transept also had apses on the east side). On the north side of the chancel there was the oldest, Romanesque sacristy. The western façade was erected as a westwork with a representative room between the towers on the first floor, with three bays of the vault. It was to house a chapel for the needs of the royal family. Its representative status was evidenced by good lighting from the west and sides, as well as an independent entrance from the ground floor, by stairs in the thickness of the wall, and a portal on the north side of the main entrance. The interior of the short nave and the transept was covered with cross-rib vaults. The bays were separated by arch bands resting on semicircular shafts, gathered in bundles and based on four-sided pads.

During the removal of the damages caused by the Mongol invasion, the southern tower was re-erected or completed, provided with two small arrowslits. The westwork was also abandoned, transformed into a gallery. In the ground floor, this gallery was vaulted by six cross-rib bays, supported by pillars, of which the two western ones also carried the inner corners of the towers. Their presence in the ground floor was practically invisible, the towers had full internal walls only from the first floor. The vast gallery (nearly 100 m2) was opened to the nave by a wide arcade. The Romanesque west façade was divided by arcaded friezes and corner lesenes. The Romanesque two-light windows were placed in the four-sided towers, covered with pyramidal cupolas, while from the west, between the towers, an oculus with a tracery filling was placed. The walls were fastened with a plinth with a moulded cornice, and from the end of the 13th century with western buttresses. The entrance led through a stepped portal located on the axis, flanked by columns, the extensions of which surrounded a semicircular tympanum. The entire entrance was embedded in a shallow avant-corps protruding from the façade, topped with a triangular gable and a diagonally led frieze of arcades mounted on small consoles.

In the fourteenth century, the need to increase the capacity of the nave led to the addition of two chapels to the space between the eastern wall of the transept and the north and south walls of the chancel. From the north, a single-bay chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary was created, while from the south, a single-bay chapel of Corpus Christi. These changes had to be accompanied by the transformation of the roof of the entire building. In addition, on the south side of the nave, a two-bay sacristy was built, also serving as an archive and treasury, transformed into another chapel in the 15th century. The early Gothic reconstruction was also associated with the creation of a new, higher vault, and therefore the construction of a new roof truss. The interiors were then given new plaster, which covered the old damages caused by fire.

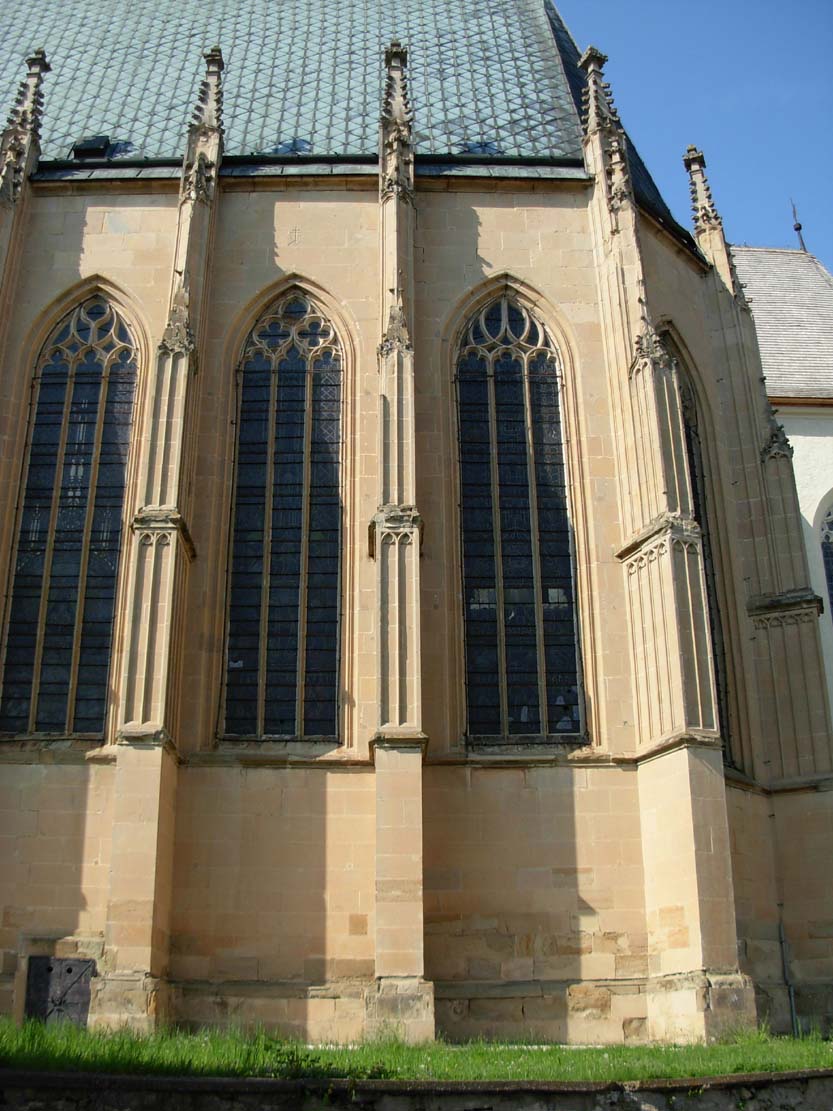

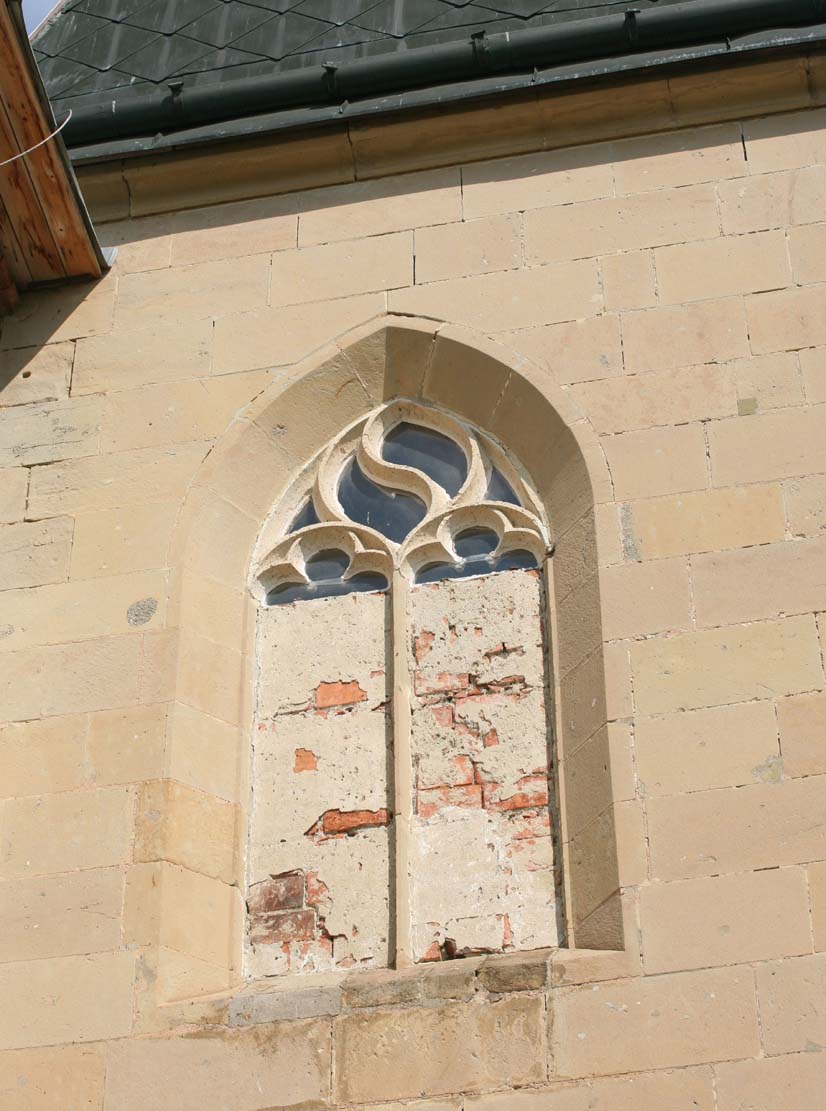

The great Gothic reconstruction from the years 1462-1478 resulted in the removal of the eastern apse, which was replaced with a spacious, polygonal chancel, enclosed from the outside with stepped buttresses, between which large, ogival windows with tracery were placed. The internal space of the church was also unified by demolishing the eastern walls of the transept and the walls between the central nave and the side chapels, replaced by high, pointed arcades. Finally, the Romanesque church turned into a transeptless pseudo-basilica consisting of nave with two aisles, preceded by a two-tower façade from the west and a polygonal chancel in the east. The Romanesque character was preserved in the western part of the church, covered with a cross vault, with the nave supported on massive pillars, while the remaining parts of the church were already Gothic. The entire church was covered with a common gable roof, multi-slope over the closure of the chancel. Inside, in the eastern part of the central nave, a net vault with moulded ribs and stellar vaults in the aisles (including the former chapels of the Virgin Mary and Corpus Christi) were installed.

From the south, at the end of the 15th century, a late-Gothic Zápolya Chapel was added to the nave. Built on the plan of a slightly elongated quadrangle with three rectangular bays, it was closed in the east with a polygonal bay (five sides of an octagon) and covered with a high gable roof. In addition, a small vestibule was placed on the west side, also in contact with the sacristy. The chapel received a rich architectural detail from the outside. The windows were filled with four-light and three-light tracery, and the buttresses surrounding the building were decorated with blind tracery and topped with pinnacles with crockets and fleurons. Inside, a net vault was established, while a crypt was created under the ground floor of the chapel. In connection with the construction of the chapel, a room for a library was also erected on the first floor above the southern sacristy. For the needs of the archive, the older northern sacristy was also enlarged, extended by two rooms on the first floor.

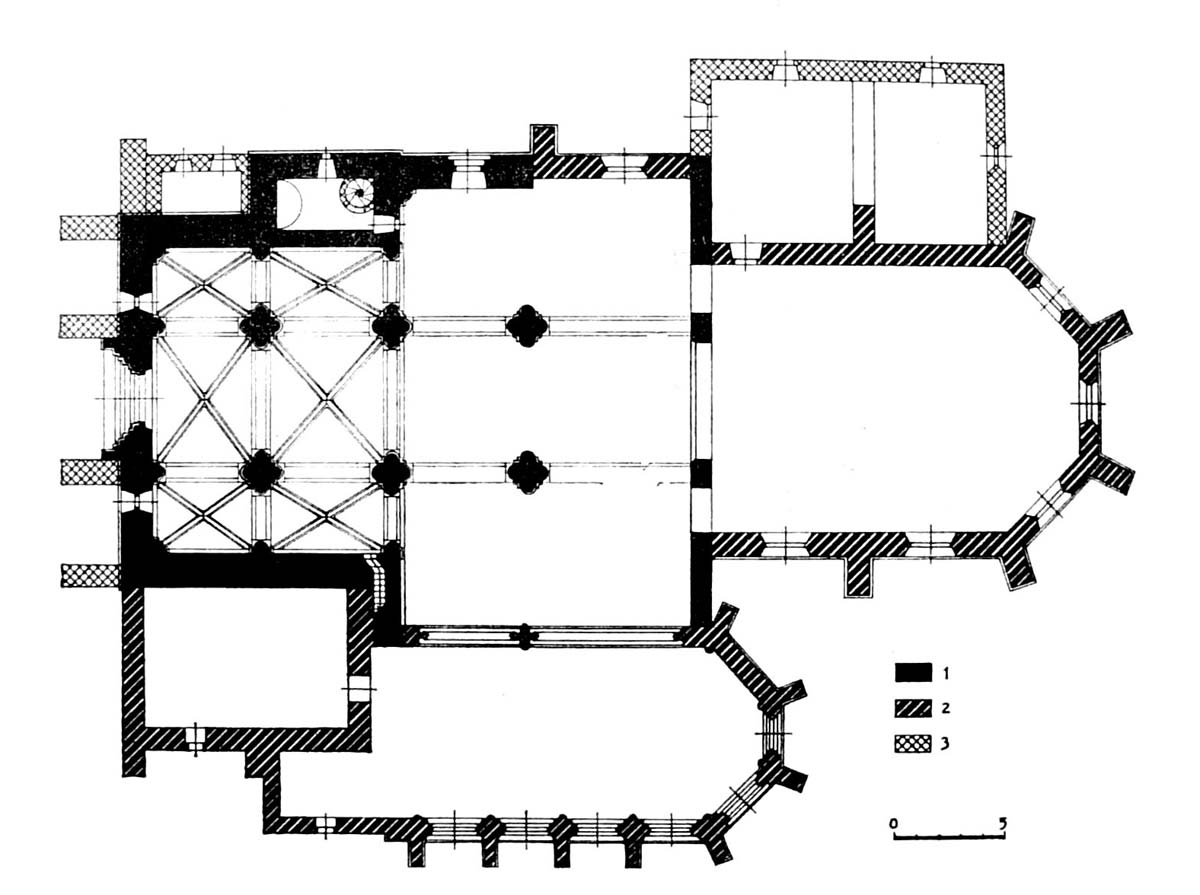

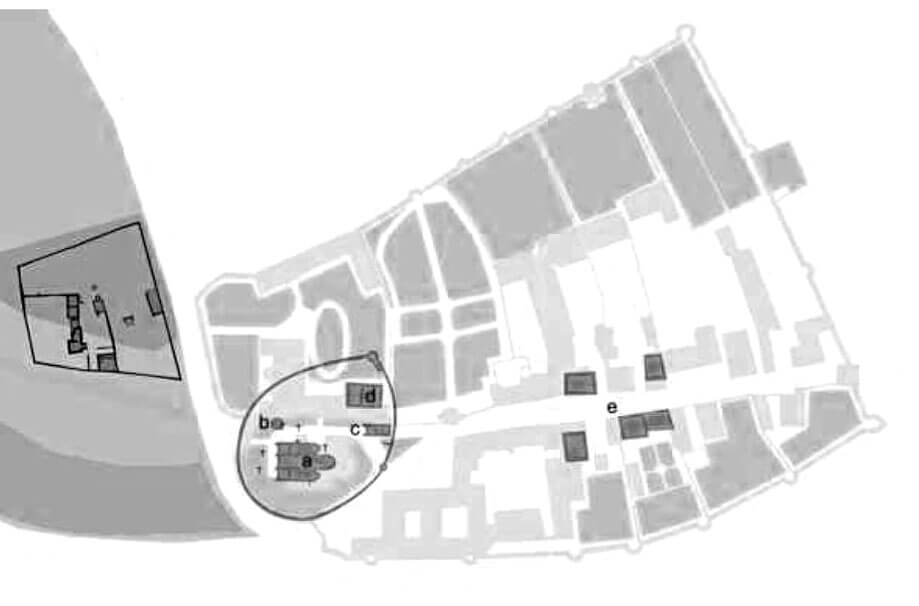

From the second half of the thirteenth century, the church of St. Martin was surrounded by a perimeter of a stone defensive wall on an oval plan. This wall had a wall-walk on the offset, protected by a crenellated parapet. In the line of fortifications there were two or three small, round towers, protruding on both sides in front of the curtains and not much higher than them. The gate to the courtyard was on the west side, and initially, until the 16th century, it was a portal without any gatehouse. The auxiliary gate in the eastern part of the courtyard, facing Spišské Podhradie, had a similar form. On the north side of the tower, at the façade, there was a rotunda of St. Andrew, built of white, travertine, carefully worked ashlar. Its internal space was very small, reaching a diameter of about 5 meters (outer diameter was about 7 meters), which allowed only about 5-6 people to enter. On the eastern side of the church, there was another chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, renamed later to St. Valentine. It consisted of a rectangular nave, semicircular or polygonal in the east, and a small tower on the west side. Near it, also on the eastern side of the church, there was a circular building with a diameter of 6 meters. It was either a charnel house or a tower, or possibly a water tank. The north-eastern part of the courtyard was filled with the oldest provost’s palace, called Muthmerianum or Mutmerium after the name of the founder – Mutimír. It was situated on a gentle slope opposite the eastern part of the church. In plan, it had a four-sided form measuring 15.4 x 10 meters.

Outside the perimeter of the defensive wall, there were cannon’s buildings, located around the road to Spišské Podhradie and further to the Spiš Castle. It were stone but simple, one-story houses, surrounded by outbuildings and gardens from the back yards. Their expansion with additional bays and various types of annexes took place in the late-Gothic style in the second half of the 15th century. From then on, a typical canon’s house was a two-story building (high ground floor and basement). The above-ground part consisted of a front hall, located from the street side, which was connected to the so-called “maashaus”, i.e. a representative room with a barrel vault or one central pillar. At the end of the 15th century, the buildings on the eastern side of the church, in addition to further canon’s houses, were supplemented by the elongated house of the parish priest, built from the foundation of the Zápolya family, and the vicarage of the local parish.

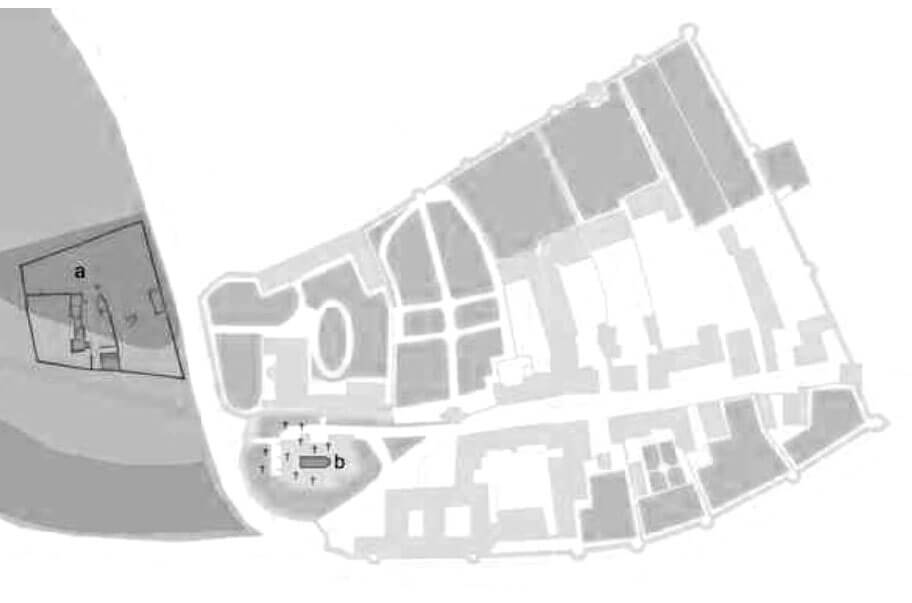

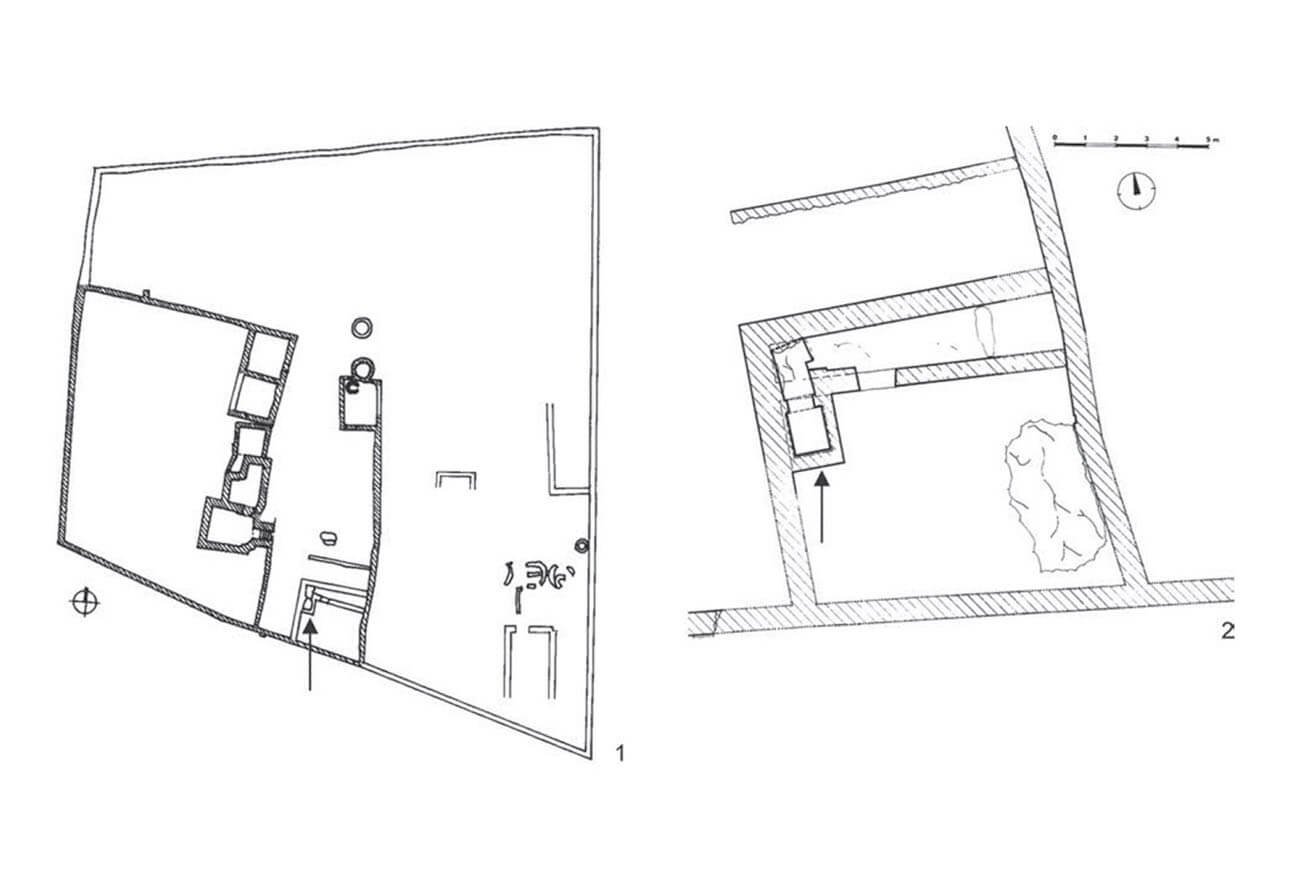

On the north-west side of the fortifications of the church since the 12th century there was a manor, taken in the 13th century by the chapter and used until the beginning of the 15th century. Built on a four-sided, irregular plan of 57 x 94 x 76 x 86 meters, it was surrounded by a wall of erratic stones, 1 to 1.3 meters thick. Inside the perimeter, in the south-west corner, there was a smaller space measuring 17 x 32 meters, the eastern part of which was made up of five adjacent rooms. The southern of these buildings was probably a chapel, because it consisted of an elongated, rectangular nave measuring 5.4 x 6.6 meters and a semicircular apse on the eastern side. From the apse, stairs carved in the rock floor led to a basement room, probably with the function of a crypt. Directly next to the chapel, from the north, another building with a basement was erected, the ground floor of which was L-shaped. It probably served as a chapter house. To the north, the row of buildings was complemented by another, smaller hall and a larger two-room building. The rooms could have been the seats of the cantor, lector and custodian. In the same phase of construction, there was also a larger residential building in the manor complex, probably intended for the provost, added to the eastern perimeter wall. It had dimensions of 9 x 10 meters, it had a basement on the north side, and in front of its northern entrance it had a wall protecting against the wind. Inside, it consisted of a large room and a passage 1.1-1.9 meters wide. In the north-west corner of the building, partly inside the room and partly in the passage, since the 14th century there was a hypocaust furnace. More or less in the middle of the site, there was a 23-meter-deep well and probably a baptistry, as well as several other buildings erected in the eastern part of the site. In the 14th century, a new building measuring 14 x 7.5 meters was added in the south-eastern corner of the courtyard, the proportions of which would indicate a representative function. The provost’s residence in the southern part of the courtyard was also modernized at that time, in which, among other things, hypocaustum heating system was installed.

Current state

Church of St. Martin is today one of the most valuable examples of late-Romanesque and Gothic architecture in Slovakia, since 1993 added on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The concept of a pseudo-basilica with a transept was unique in the region, as was the design of the western part of the church as a westwork. The facade of the church has retained its Romanesque appearance until now, while the southern Zápolya Chapel can be considered a jewel of Gothic architecture. It is worth noting that the lower part of the original body of the church, including the entire Romanesque plinth, is today underground, due to the raised of the ground level over the centuries. The effects of Baroque and 19th-century works are primarily the northern annexes of the church and the gallery inside the nave.

Church of St. Martin has preserved a huge amount of medieval architectural details and some of the old equipment to this day. Upon entering the church, a late-Romanesque stone sculpture of a lion from the second half of the 13th century attracts attention. In the chancel there is the main altar of St. Martin, composed of Gothic elements from 1470-1478. Other Gothic altars from the 15th century are located in the aisles. Fragments of a Gothic polychrome from 1317, depicting a scene from the coronation of King Charles Robert, have also been preserved in the church.

The church and the former buildings of the canons are still surrounded by fortifications. Their oldest fragment, dating back to the second half of the 13th and 14th centuries, is located on the west and south side of the church. The remaining part, adapted to firearms, dates back to the 17th century. The rotunda of St. Andrew, demolished in 1780 in connection with the Baroque extension of the bishop’s palace, and the chapel of the Virgin Mary, demolished in 1781, have not survived. The late-Romanesque palace of the provost has been preserved, but as a result of the Baroque reconstruction, it lost its original stylistic features (only one walled-up window and the original entrance were discovered in the cellars).

bibliography:

Glejtek M., Labanc P., Olejník V., Od počiatkov Spišskej Kapituly po vznik biskupstva, Ružomberok 2021.

Hanuš M., Teplovzdušné vykurovanie v stredoveku na území Slovenska, „Slovenská archeológia”, LXIX/1, 2021.

Janovská M., Olejník V., Stavebný vývoj Katedrály sv. Martina a jej okolia v Spišskej Kapitule [w:] Sanace dřevěných konstrukcí. Sborník příspěvků k odborně-metodickému semináři, Opava 2013.

Mencl V., Stredoveká architektúra na Slovensku, Praha 1937.

Podolinský Š., Románske kostoly, Bratislava 2009.

Tomaszewski A., Romańskie kościoły z emporami zachodnimi na obszarze Polski, Czech i Węgier, Wrocław 1974.