History

The stone castle on the Muráň river valley was probably built shortly after the Mongol invasion in 1241. It was most likely founded by the Hungarian King Béla IV, because it was built on the royal property. It was erected to control the route through the Ore Mountains to Spiš and further to Poland, and to protect local iron ore mines. Due to its location on a lofty and inaccessible mountain, it could also originally have served as a refuge for the local population. The first mention of the castle, in which it was named as “castrum Movran”, was recorded in document in 1271.

The castle was not in the royal hands for long, because Stephen V of Hungary gave it in 1271 to the land judge Mikulás from the Monoszlo family. Then, in unknown circumstances, Muráň could pass into the hands of the Tekuš family. As the then owners had family estates in distant places, the unused castle was to fall into decline. At the end of the 13th century, at the end of the rule of the Arpad dynasty, when the power of the noble oligarchs increased, the castle could pass under the rule of Máté Csák (Matúš Čák) or one of the families favorable to him. The lack of records of Muráň from this troubled period led to the assumption that in 1321, when Csák died and his dominion fall, the castle was destroyed, confiscated by King Charles Robert, forcibly sold or possibly abandoned. In the second quarter of the 14th century, the new owners of the surrounding estates from the Ratold family probably contributed to its rebuilding, specifically their branch from Jelšava, which in the second half of the 14th century conducted intensive settlement activity in the area of Gemer. The Ratold family owned the Muráň castle until 1427, although not a single reliable record has survived from this period. This would indicate that although the lords of Jelšava founded numerous villages in the surrounding areas, they did not care about the castle itself and did not attach importance to it. With the heirless death of Juraj of Jelšava, all his property passed to King Sigismund of Luxemburg.

In the 1440s, the insignificant, and perhaps even abandoned, Muráň was occupied by the army of Jan Jiskra, acting in the service of Queen Elisabeth, fighting together with the supporters of the Habsburgs against Ladislaus II, elected king of Hungary. At that time, the castle was enlarged and refortified. After the resignation of Jiskra, it was taken over by former fighters of the Hussite movement, who left Bohemia after the defeat at Lipany. At that time, they wandered around the country and lived off plunder, taking advantage of unclear property conditions and abandoned castle seats. In 1461, Muráň recaptured from them Štefan Zápolya on behalf of King Matthias Corvinus, thanks to which he could include it in the family estate. In order to successfully besiege the castle, Zápolya was to build a fortress (castellum) located “sub monte Mwran”, from which he was to attack Muráň with the help of the townspeople from Levoča. During the fighting, the castle was probably not badly damaged, because in 1469 it was recorded that it was managed on behalf of the Zápolya by a certain Pavel from Plešivac, who was supposed to invade the subjects of Helena, the widow of Ondrej from Štítnik, and imprison them in the Muráň Castle.

At the end of the 15th century, the castle was expanded by the Zápolya family, wealthy magnates and commanders who headed each important expedition of Matthias Corvinus outside the borders of the Hungarian kingdom. At that time, Muráň gained in importance at the expense of the castle in Jelšava. The decisive factor was probably the desire of the Zápolyas to control the roads to Spiš, where they had their ancestral property base. Muráň was also perfect for protecting local goods. Štefan Zápolya, and then his son Ján, appointed their most loyal family members as castellans and officials in the castle, such as Juraj from Putnok, Krištof from Smrečian, or Ján and Jakob from Tornale. Ján was first recorded as a castellan in 1523, when he issued a document in connection with a murder committed in the house of the mayor of Revúc, as well as the looting of the house of a member of the guard of Murán Castle. Jakob of Tornale was mentioned in the rank of castellan of the castle in 1528, in the reimbursement document of the expenses he incurred in connection with the construction of fortifications and the maintenance of a large garrison.

With the death of Jakob of Tornale between 1528 and 1531, four-year-old Ján became the owner of the castle. The legal guardian of the minor heir, Matej Bašo, sent the boy to study in Poland, and together with his brothers, he took over the castle, making it a seat for robbery activities throughout Gemer. Only in 1548, after a long siege, the castle was recaptured from the raubritters by Count Nicholas of Salm. The garrison of 150 soldiers and 50 civilians was then besieged by an army of about 3-5,000, which built two fortresses under the castle, preventing Muráň from being supplied with food and weapons. For 12 days it was conducted intense artillery fire, during which 1,700 missles was fired. Then the infantry conducted a bloody, unsuccessful assault. Bašo’s two brothers were badly wounded in the battle, so he himself was determined to negotiate, but when his terms were not accepted, he was betrayed by part of the garrison who let the besiegers through the back gate at night. Matej Bašo secretly escaped from the castle, but was caught near Telgárt. After the capture, the stronghold was included in the property of the king and, for fear of the Turkish threat, it was staffed with a strong garrison. The Muslims reached the immediate vicinity of the castle in 1556, 1558, 1562, 1569, 1570 and 1574. Each time their looting the village under the castle, while in 1556 the troops of František and Juraj Bebek cooperated with the Turks. The castle was besieged in 1577, but the Ottoman army failed to capture it.

The military importance of Muráň diminished after the Fiľakovo Castle was recaptured in 1594. In 1602, the castle was pledged for three years to captain Julius Herberstein, due to the fact that he maintained it for a long time at his own expense. In 1605, Emperor Rudolph II gave the castle to his favorite Carinthian nobleman, Johann of Rottal, but already in 1612 Muráň together with the feudal estate was bought by Tamás Szèchy, the main zupan of Gemer. After him, the castle was ruled by his son György, and after his death in 1625, his widow, Mária Drugeth. Her daughter, also named Mária, beautiful and intelligent, nicknamed “Venus of Muráň”, was initially a loyal ally of Emperor Ferdinand Habsburg. In 1644, with a night attack, she gained control of the castle at the expense of her brother-in-law Gabriel Illeshazy, who was on the side of the insurgents of György Rákóczi, and then married Ferenc Wesselényi, the commander of the fortress in Fiľakovo. In 1655, Wesselényi became the palatine of Hungary, but in 1666 he headed an anti-Habsburg conspiracy of Hungarian magnates, as a consequence of which all his goods were confiscated. After the death of Ferenc, Mária defended the castle for four years, but was finally captured by the army of Charles V of Lorraine in 1670. This date marked the end of the splendor of Muráň.

In 1683, the castle was occupied by Imre Thököly, the leader of the great anti-Habsburg uprising, although it was recaptured by the imperial army the following year. After the final fall of the uprising, in 1688, Muráň was taken over by the royal commissioners, before it was handed over to Count Štefan Kohára a year later, as a reward for loyal service. In 1702, the castle burned down, and the occupation of the anti-Habsburg insurgents in 1704, who produced armaments for the fighting rebels on the castle mountain, contributed to the even worse condition of the buildings. In the following years, major repair work had to be carried out, as the supporters of Rákóczi appointed Muráň as the guardian of the crown jewels. Its garrison was commanded until its fall in 1709 by Nicholas Bercsényi. With the return of the castle to the estate of the Koháry family, it began to decline in the mid-18th century. The damages were stopped to be repaired, even the most urgent works were not invested, until finally, in 1776, the imperial garrison was withdrawn from the castle. From that moment, Muráň fell into complete ruin until the second quarter of the 19th century.

Architecture

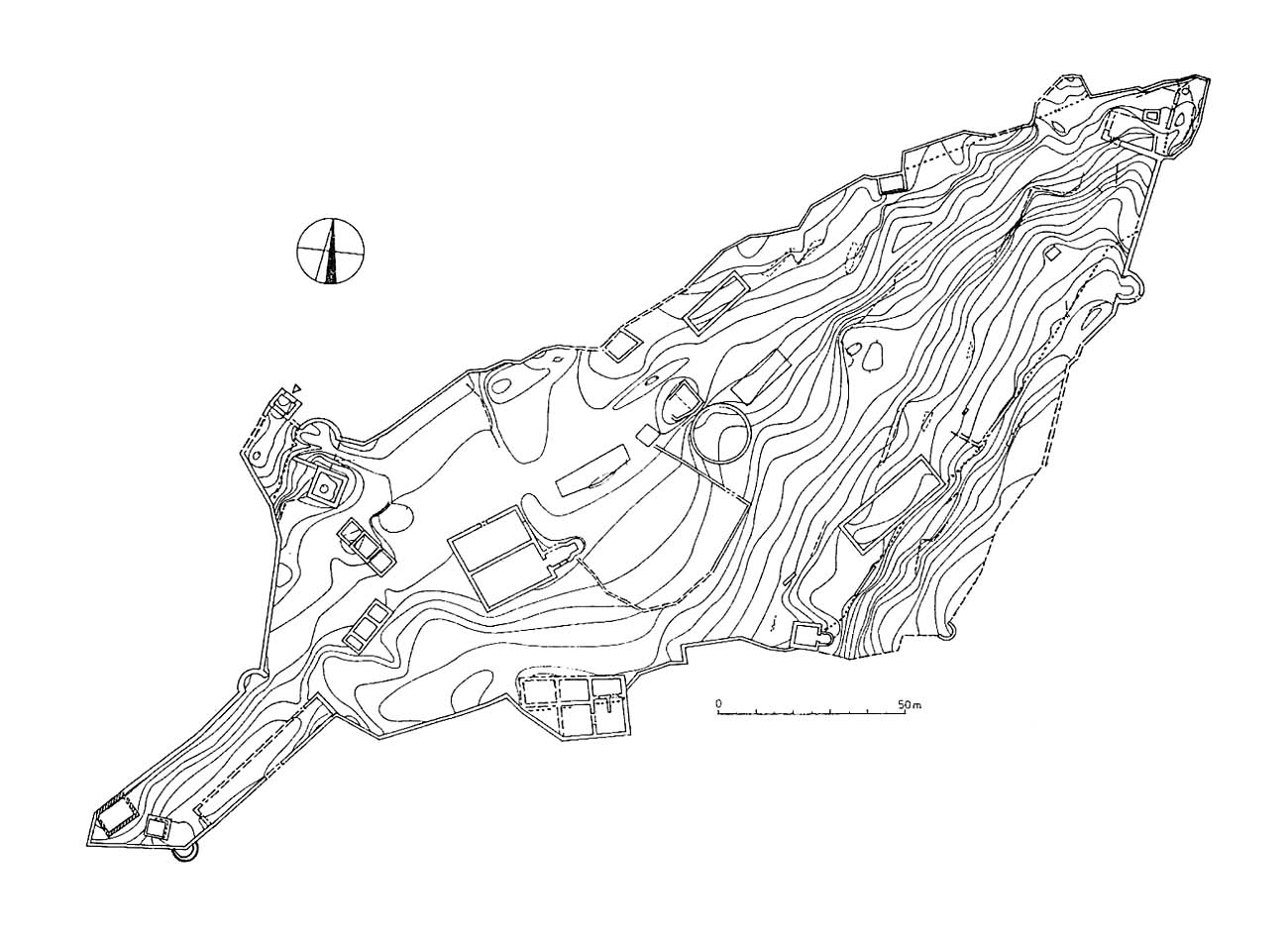

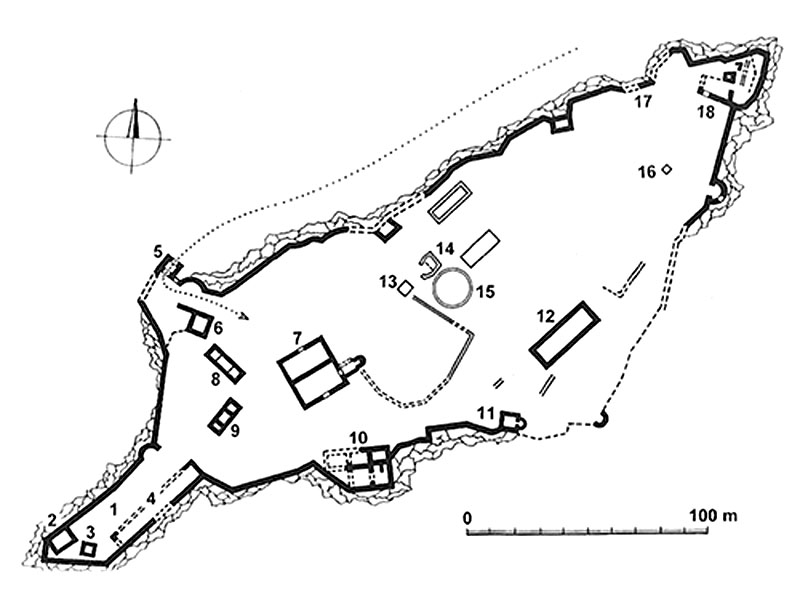

The oldest, Gothic buildings of the castle were erected in the south-western part of the Cigánka Mountain ridge (935 meters above sea level), on its rock promontory providing a view into the valley of the Muráň River (called Jelšava in the Middle Ages). The entire, flattened top of the ridge provided excellent defensive conditions, because it was limited on virtually every side by high and steep, rocky escarpments. The longitudinal axis of the ridge, in the south-west and north-east directions, ran parallel to the route at the foot of the mountain on the eastern and southern sides, as well as to the access road that was marked out on the opposite side. This road climbed along the slope from the north-east, where the Cigánek ridge was connected to a larger and higher hill.

On the south-west promontory of the mountain, a residential tower with dimensions of 11 x 8 meters was located (the internal space on the first floor was 5.6 x 8.8 meters). The thickness of its walls was not too large and was about 1 meter. Next to it was a cistern carved in the rock, supplying the inhabitants with rainwater. It was covered by a one-story building with a four-sided outline. The protection of the castle at that time was a ditch carved in the rock, about 7-8 meters wide, separating the stronghold from the rest of the mountain. This remaining part of the hill was probably used as an economic base in the 14th century.

The rebuilding of the castle from the 15th century resulted in its extension to an area with maximum dimensions of 370 x 180 meters and almost 2.5 ha. The defensive walls of the castle surrounded the entire top flattening of the mountain, adapted to the configuration of the terrain. It were not high due to standing over several dozen-meter cliffs, but were equipped with a wall-walk for defenders and battlements along their entire length, supplemented in some places with loop holes at ground level, intended for firearms since the end of the Middle Ages. The walls were strengthened by a few towers, located in sensitive places from the point of view of defence. One (visible in the panorama from 1549) was probably located in the north-eastern corner, where it towered over the access road to the castle. Another could be on its western side. A defensive role could also be played by an elongated building attached to the northern section of the perimeter wall. At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the defensive walls were additionally strengthened by three semicircular towers, opened from the side of the courtyard. One was in the west and two in the eastern part of the fortifications. Their greater number was not necessary due to the excellent natural conditions of the terrain.

The entrance to the castle, preceded by wide stairs carved in the rock, was from the north-west side. It was guarded by a four-sided gatehouse, behind which there was a small courtyard of the foregate, and then fortifications, the main element of which was a massive four-sided tower measuring 8.7 x 8.7 meters, behind which a free-standing building for guard was located. In addition, in the north-eastern part of the castle there was an elevator for transporting heavy loads to the castle hill, protected by the tower mentioned above, placed in the corner. Its functioning certainly facilitated and accelerated the delivery of supplies and construction or military materials to the castle.

In the first half of the 16th century, in the times of the Zápolyas, in addition to numerous smaller buildings, a large palace was erected, adjacent to a separate courtyard and a rainwater tank from the east. According to records, at the end of the Middle Ages, the castle also had a horse mill, a kitchen with a bread oven, stables, cellar chambers for wine and grain, a brewery, numerous pantries, and in the mid-16th century even a cannon foundry. In addition to the residential buildings of the castellan and his family, the castle had to have rooms for a large garrison. Some of the rooms must have been used as armouries, a prison or the torture chamber mentioned in 1584. According to the surveys, military equipment was hidden in various places: in the foundry workshop, in the room under the gunpowder tower, in the room under the gate, in the tower called the Jewish Tower and in the tower called Gypsy Tower, as well as in the houses of the trumpeter, captain, baker, artillery commander and keykeeper.

Current state

Muráň is one of the largest castles in Slovakia. It has an unusual layout, which consists of a large number of detached buildings spread over a vast area. Most of them are in ruin, but they are gradually being renovated. Currently, the best preserved elements of the castle are the square northern tower and the gatehouse. The remaining, few relics of buildings are among bushes and trees. Of these, the main residential house in the central part and the southern one, attached to the defensive wall, have been best preserved. In the south-west, the oldest part of the castle, a viewing platform was set up. In addition, large sections of the defensive wall have been preserved.

bibliography:

Bóna M., Plaček M., Encyklopedie slovenských hradů, Praha 2007.

Bóna M., Tihányiová M., Najstaršie vyobrazenie hradu Muráň, “Pamiatky Mureň”, 2/2015.

Janura T., Tihányiová T., Šimkovic M., Hrad Muráň z pohľadu najnovšieho archívno-historického a architektonicko-historického výskumu [w:] Najnovšie poznatky z výskumov stredovekých pamiatok na Gotickej ceste II, red. M.Kalinová, Bratislava 2018.

Wasielewski A., Zamki i zamczyska Słowacji, Białystok 2008.