History

The construction of the Lietava Castle (Litova, Letava, Zsolnalitva) began in the second half of the 13th century, probably on the initiative of Byter, the ancestor of the Balass family, who had landed estates in the area since 1254 and who, thanks to the castle, could control the Rajčanka river valley and defend the northern border of the kingdom Hungarian. For the first time, the castle was indirectly recorded in documents in 1316, while it was directly mentioned in 1321.

At the end of the 13th or at the beginning of the 14th century, the castle was taken over by the palatine Máté Csák (Matúš Čák), sovereignly ruling part of the then Hungarian kingdom (the western part of today’s Slovakia). In 1316, the palatine ordered Albert, a member of his family, to collect due fees from the estates called Lytwa, and two years later the castellan Andrej of Lietava was recorded. After Csák’s death in 1321, the castle was taken by King Charles Robert, and then Louis I of Hungary. In 1360, Lietava was given “pro honore” to the land judge Štěpán Bebek, so he and subsequent judges could use the castle and its income while traveling around the country related to the performance of the office. At the end of the 80s of the fourteenth century, Ján of Kapla became the highest judge of the kingdom (iudex curiae regiae), who demanded from Sigismund of Luxemburg that the castle could be used by his brother, the zupan of Nitra, Dezider of Kapla. He received Lietava together with Hričov and Rajec in 1392 as a pledge, and after three years as hereditary property, but before 1398 Sigismund took Lietava from him under unknown circumstances.

At the end of the fourteenth century, the castle was given by king to Sędziwój of Szubin, the voivode of Kalisz and regent of the Polish kingdom after the death of Louis I of Hungary. Probably after the death of the voivode, the Lietava estates passed into the hands of his son-in-law Stibor of Stiboricz, a close associate of Sigismund of Luxemburg, and then his son Stibor II. Their main seat was the Beckov Castle, which is why they gave Lietava to their cousin Mikołaj Szarlejski. Mikołaj owned the castle even after Ścibor’s death in 1434, when the family dominion fell apart and he himself was accused of being unloyal to the king. He was helped in this by the Polish crew of Dunin from Skrzynno, a relative of Mikołaj. In 1437 Szarlejski withdrew to Poland, but the Polish garrison remained in Lietava until at least 1439.

Around the middle of the 15th century, the castle returned to the hands of the Hungarian king. For over twenty years it did not appear in documents, until only in 1474 Matthias Corvinus gave the castle together with all the property to Pál Kinizsi, as a reward for loyal service in military expeditions against the Turks, during which Pál was wounded many times and hired troops from own treasury. Thanks to the new owner, the largest, late-Gothic expansion of the castle took place in the years 1475-1494. Kinizsi himself, however, did not stay permanently in Lietava, which, together with Strečno, he handed over to the castellans. From around 1484, this office was held by Teofil Thurzo. The next owner of the castle was since 1492 palatine István Zápolya, from whom Pál borrowed huge sums to defend the borders of the kingdom.

Pál Kinizsi died childless and never returned the borrowed sums, so until the Battle of Mohács, the official owners of Lietava was the rich Zápolya family. Around 1512, however, they handed over the castle to Mikołaj Kostka from Poland. During his time there were numerous disputes with the Podmanicki family, who owned numerous properties in the area. Disputes were also part of the internal conflicts of the kingdom, which after 1526 was torn apart by the war between the Habsburgs and the Zápolyas. In the course of them, Ferdinand I even confiscated Lietava and handed it over to his supporters in 1543, although it was only on paper with no real consequences. The daughter of Mikołaj Kostka was married to a rich magnate, Francis Thurzo, with whom, after 1558, further development of the castle and rebuilding of the interiors in the Renaissance style was related. At the beginning of the 17th century, it became a strong fortress where the Thurzons protected their most valuable possessions during wars and unrest.

In 1616, the Hungarian palatine George Thurzo died, and his only son Imre passed childless five years later. The castle became the common property of the sisters and daughters of the deceased. The ownership situation, which was difficult to regulate, meant that no one wanted to get involved in maintaining the stronghold, so in 1698 it was almost abandoned. In 1708, the castle took part in the armed conflict of the anti-Habsburg uprising for the last time. Lietava was first occupied by the rebels, and then by the imperial army remaining in the castle until 1714. Later, the dilapidated building housed the family archive, which was moved to the Orava castle in the years 1760-1770. In the 19th century, Lietava Castle fell into complete ruin.

Architecture

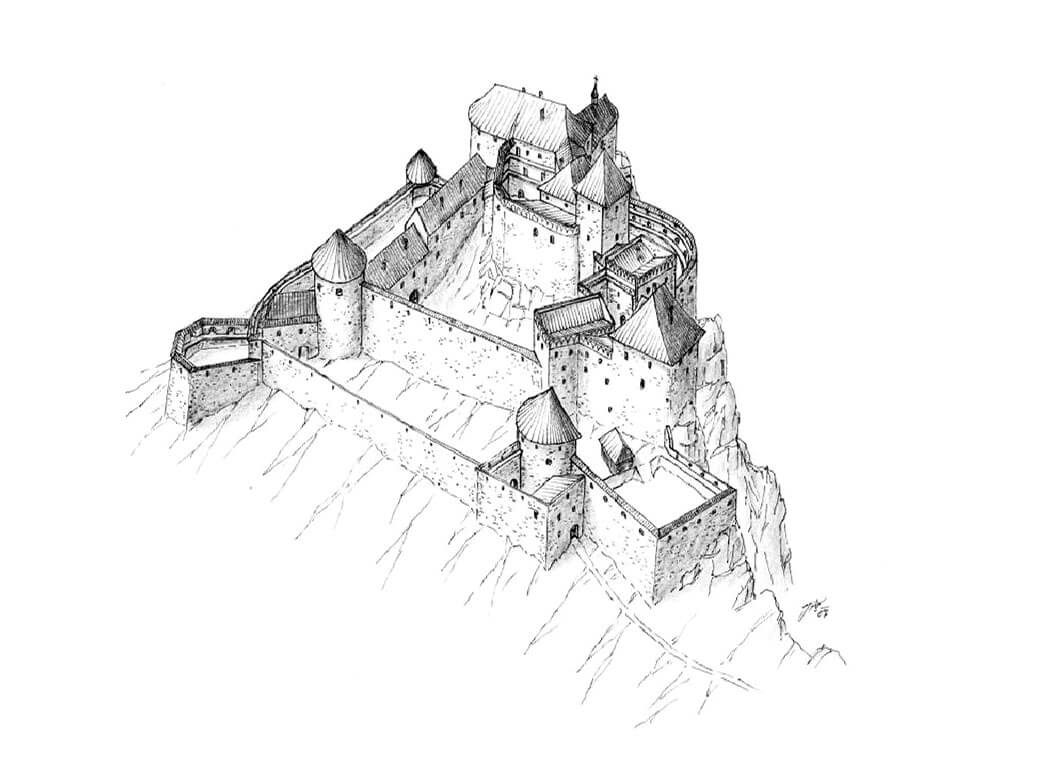

The Lietava Castle was erected on a high hill that controlled the valley of small streams Lietavka and Svinianka, both of which had an outlet in the Rajčanka River flowing a little further to the east. Rocky, vertical cliffs greatly protected the castle from the east. Also in other directions, the slopes were steep and very high, only from the south-west a more accessible approach was connected with a ridge descending to the west, which could lead the road from the valleys from the north and south to the castle.

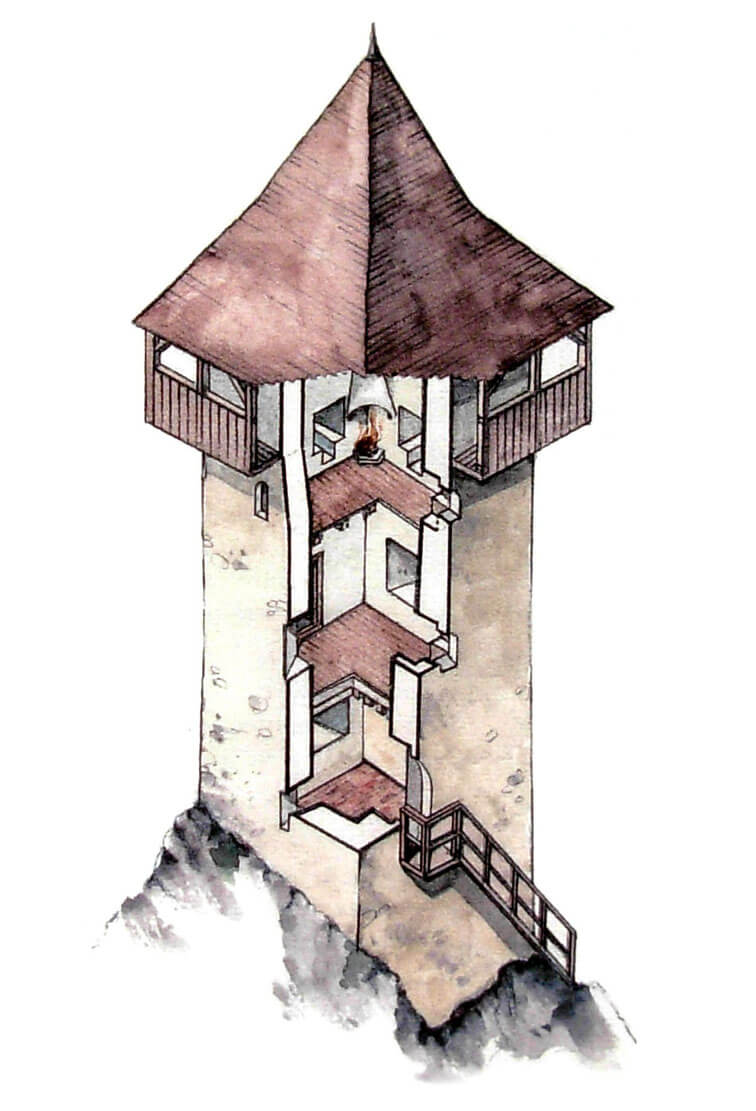

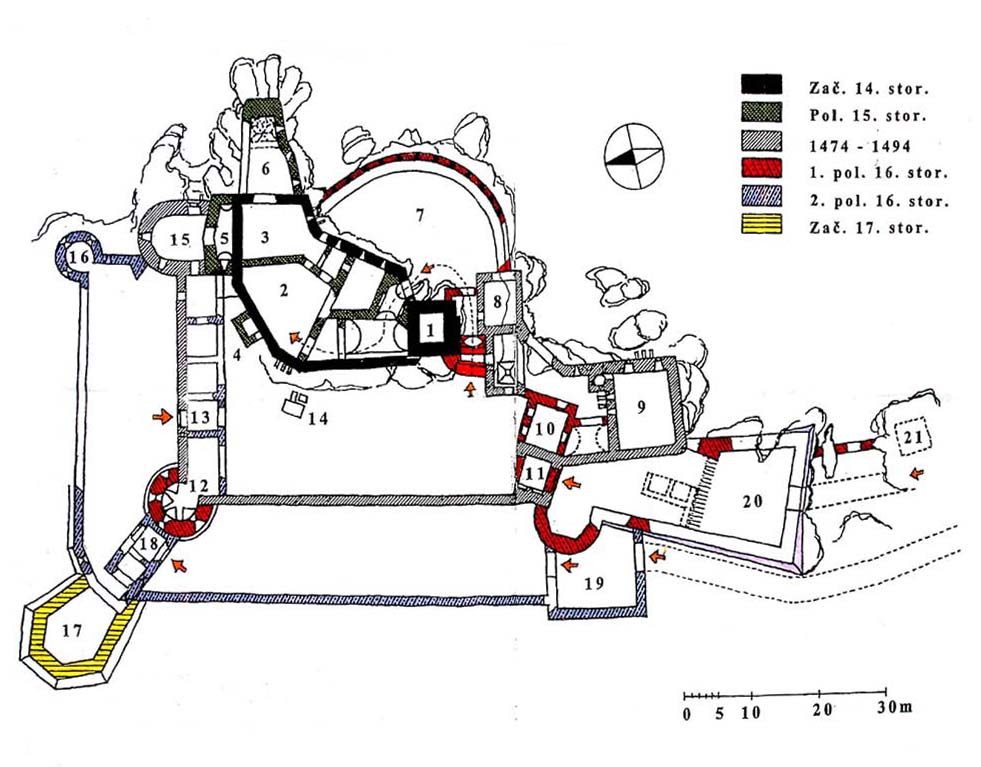

The original medieval building was limited to the later upper ward, whose irregular perimeter of the walls was adapted to the shape of the rocky terrain. The defensive wall was led along the edges of the cliffs, especially high on the eastern side. The oldest complex also included a square tower with dimensions of 6×6 meters, located at the highest point of the rock, connected by its northern corners with a defensive wall, separating a curved courtyard on its northern side. The access road to the castle at the end of the 13th century led from the south, passed under the tower, and then over a wooden bridge reached the northern portal of the gate leading to the courtyard.

The keep tower had three floors separated by timber, flat ceilings, accessible through the entrance from the side of the courtyard, set at a height of several meters, to which a ladder or wooden stairs had to lead. It opened to the level of the first floor, illuminated similarly to the two higher ones with narrow, slit openings. The windows were splayed to the inside, despite the small size on the second and third floors equipped with side sedilia. In addition, at the level of the second floor, there was a passage to the latrine projection, and the room on the third floor was heated by a corner fireplace. The upper part of the tower was surrounded by a timber guard and defense porch.

In the fourteenth century, the residential space of the castle was too small for the needs of the then inhabitants, so the perimeter of the walls was extended to the entire top of the rock promontory, obtaining a crescent-like shape in plan. Its thickness was not even. The southern and eastern, better protected parts, also using fragments of the older wall, were only about 1 meter thick, while from the north, where the pointed portal of the gate was located, the walls were more massive. The eastern end of the courtyard was filled with a residential building equipped with a large wooden latrine set over a rock escarpment. Probably still in the 14th century, the residential building was enlarged by a second bay, added to the southern defensive wall, and until the first half of the 15th century, the buildings filled most of the northern part of the courtyard, so that they occupied a characteristic, narrow, corner promontory. A castle chapel was situated there, topped with a net vault since the reconstruction at the end of the 15th century.

Among the buildings from the first half of the 15th century was a tower-like, rectangular projection, added to the outer face of the wall on the north side (the so-called Oblong Tower), situated in the place of the original gate. Its portal was bricked up than, and a new entrance was created in a rock cleft on the south side of the castle, under the protection of the neighboring main tower. The reconstruction from the second half of the 15th century enlarged the upper ward with a new residential wing located in the south-east, by the keep. The entrance to the courtyard located there had to be led through the new part, protected by a drawbridge over a rock cleft. Presumably, during this period, a small avant-corps of the latrine was also erected, added from the north-west to the defensive wall of the upper ward, extended towards the outer bailey. The walls of the upper ward were raised at the end of the 15th century and equipped with a wooden hoarding porch on the north-west side. A wooden porch also connected the eastern and western parts of the residential buildings from the side of the courtyard.

During the great expansion of the years 1474 – 1492, a second, larger courtyard was added on the west side, initially serving as an outer bailey. From the south, it was ended by a four-sided tower house located on a rock outcrop, next to which a four-sided gatehouse with a drawbridge was erected in the bend of the wall. The defensive wall of the outer bailey (later middle ward) was also reinforced with a horseshoe tower in the north-west corner, and a more elongated and higher tower in the north-east corner (the so-called Red Tower), added on the extension of the rectangular projection from the first half of the 15th century. Both buildings were adapted to the use of hand-held firearms (key loop holes in the ground floor), but the north-eastern one also had residential functions. In the south-eastern part of the courtyard, on the opposite side of the old keep and the passage to the upper ward closed with a portcullis, there was a kitchen building measuring internally approximately 6.5 x 6 meters, dominated by a large chimney of the furnace. Its erection was technically difficult, because it occupied the edge of the rock and the gap between two stone blocks. The culmination of the great expansion of the outer bailey was building of a new well in the courtyard, necessary for the functioning of the enlarged castle.

The late-Gothic four-sided tower house was the front of the castle in the 15th century, so it was the most massive building in the whole complex, reinforced in the corners with carefully worked ashlar (one of blocks bears the coat of arms of the owners of Lietava). It had dimensions of approximately 15 x 15 meters, with one room on each of the three original floors, with the second and third levels decorated with wall paintings, serving residential functions. On the third floor, heating was provided by a fireplace, there was also a passage to a latrine suspended over the slopes on the eastern side. The floors were accessible through a spiral staircase placed in a projection in the corner of the courtyard. For defensive reasons, the staircase was also connected to the wall-walk in the crown of the defensive wall.

In the first half of the 16th century, the entrance to the lower part of the castle was first preceded by a vast foregate, based on the slopes of the hill and a residential tower from the east, and from the west, right next to the gate tower, equipped with a semicircular half tower. Quite quickly, however, the entrance to the castle was changed, moved it to the better protected northern side. The old gate was bricked up, and the new entrance was located on the opposite side, in a wall flanked by two horseshoe towers. The north-western tower, which from then on played a key defensive role at the entrance road, was thickened. Work on it was probably carried out at the same time when another, lower part of the castle was built, consisting of courtyards on the west and north side, through which the entrance road was led. The walls of the lower ward were reinforced with a small north-eastern horseshoe tower and two new gatehouses: the outer one and north-western one between two new courtyards. From now on, the road to the upper ward led through a total of five gates.

In the middle ward, works from the first half of the 16th century enlarged the buildings by a wing added to the former gatehouse, also in contact with the kitchen in the corner. On the eastern side, the castle’s defense was increased by a semi-circular, large barbican with a diameter of 25 meters. Pierced with large loop holes for cannons and smaller loop holes for small arms, the barbican controlled the valley on the eastern side of the castle, which one of the trails led to Lietava. It also served as an arsenal in which the equipment and armament of the castle garrison were stored. In the eastern part, there was a cellar with a small postern at the junction of the wall with the rock.

Current state

The castle has survived as a ruin in the form from the 15th-17th century with visible elements of the oldest layout. Among other things, the upper ward has a square main tower, up to a height of about 14 meters (keep), with an opening after the original entrance portal. In addition, in the lower and middle parts of the walls, fragments of fortifications from the 13th/14th century are visible, including the imprints of beams of hoardings installed from the north-west. In the place where the eastern residential building from the 14th century functioned, on the outer façade next to the early modern windows, there are visible openings of a timber projection. On the southern side of the palace a moulded late-Gothic window has also been preserved in good condition. In the middle ward in the best condition there is a horseshoe tower, a corner tower rebuilt in the 16th century and a southern tower house. It is also worth paying attention to the kitchen arcade stretched between two rocks, visible from the outside. The lower ward with two gates has been preserved in the worst condition. The effect of early modern transformations is the top floor of the southern tower house from the second half of the 16th century, most of the large windows, Renaissance attics covering defensive porches, remains of vaults in the rebuilt rooms, bastion fortifications of the lower ward and a transformed external gate. Currently, conservation works are being carried out in Lietava, the aim of which is to secure and make the ruins available to visitors.

bibliography:

Bednár P., Bielich M., Križková L., Lietavský hrad vo svetle najnovších archeologických výskumov. Predbežné výsledky archeologického výskumu v roku 2011 [in:] Zamki w Karpatach, red. J.Gancarski, Krosno 2014.

Bóna M., Bielich M., Janura T., Šimkovic M., Hrad Lietava, Bratislava 2016.

Bóna M., Plaček M., Encyklopedie slovenských hradů, Praha 2007.

Wasielewski A., Zamki i zamczyska Słowacji, Białystok 2008.