History

The oldest record of the Franciscans in Levoča was noted in documents in 1272, when Bonaventura da Bagnoregio in the list of Franciscan convents in Hungary mentioned two monasteries in Spiš (“Ceps superius and Ceps inferius”). It is not known when the monks came to Levoča. It probably happened after the foundation of the town, i.e. after the Mongol invasion of 1241-1242 (the oldest record of Levoča – Leucham was made in the document of King Bela IV from 1249, while as civitas Levoča was recorded for the first time in 1271). Presumably, the convent was founded in the 60s or early 70s of the 13th century. Its original seat was probably wooden buildings, perhaps erected at the small church of St. Nicholas.

The stone Franciscan friary and the adjacent church began to be built in Levoča at the beginning of the 14th century. According to late records, it was to take place in 1308 on the initiative of a certain Dank, identified with Donch (Donč), one of the greatest Upper Hungarian nobles of that time. The founder could also be Kokoš Berzevitzy, who in 1307 was convicted of the murder of a certain Fridrich, son of Arnold of Hrhov. As penance, he was ordered to make a pilgrimage and, in addition, to establish six monasteries. The construction was generally completed around the middle of the century. The claustrum rooms must have functioned in 1345, when a document of the noblemen Ján and Mikuláš, sons of a certain Rikolf of Kamenica, was issued in them. Finishing of the monastery church of St. Ladislaus probably lasted a bit longer, until the end of the 14th century.

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, the Franciscan Friary of Levoča was one of the main monastic centers in the Spiš region. Like most buildings in the Middle Ages, it was subject to frequent fires. It probably burned down during the town fire of 1431, and then in 1485. After the latter, the reconstruction was carried out in the late-Gothic style. The poor technical condition of the monastery buildings at the beginning of the 16th century required extensive renovation works, which were carried out by the town builder Melchior Messinsloher, father-in-law of the well-known master Pavel of Levoča, working, among others, at the parish church of St. James.

In the years of the Reformation, the monastery complex passed into the hands of Protestants. The Franciscans left the town in 1544, and the town officials allocated their buildings for warehouses. The monastery church served the Evangelicals until the Counter-Reformation in the second half of the 17th century. In 1671, the church and the friary were taken by the Jesuits, who took over the monastery buildings destroyed by fires in 1580, 1599 and 1638, and then subjected to long-term neglect. After 1671, they started a thorough reconstruction of the friary in the Baroque style, although the church was still mostly in the Gothic style. After the Jesuits, the Minorites settled in the monastery, and from the beginning of 1810, the Premonstratensians. In addition, there was a gymnasium in the friary buildings. Finally, in 1851, the neglected monument was taken by the town, which in 1913 erected new buildings in the immediate vicinity of the monastery.

Architecture

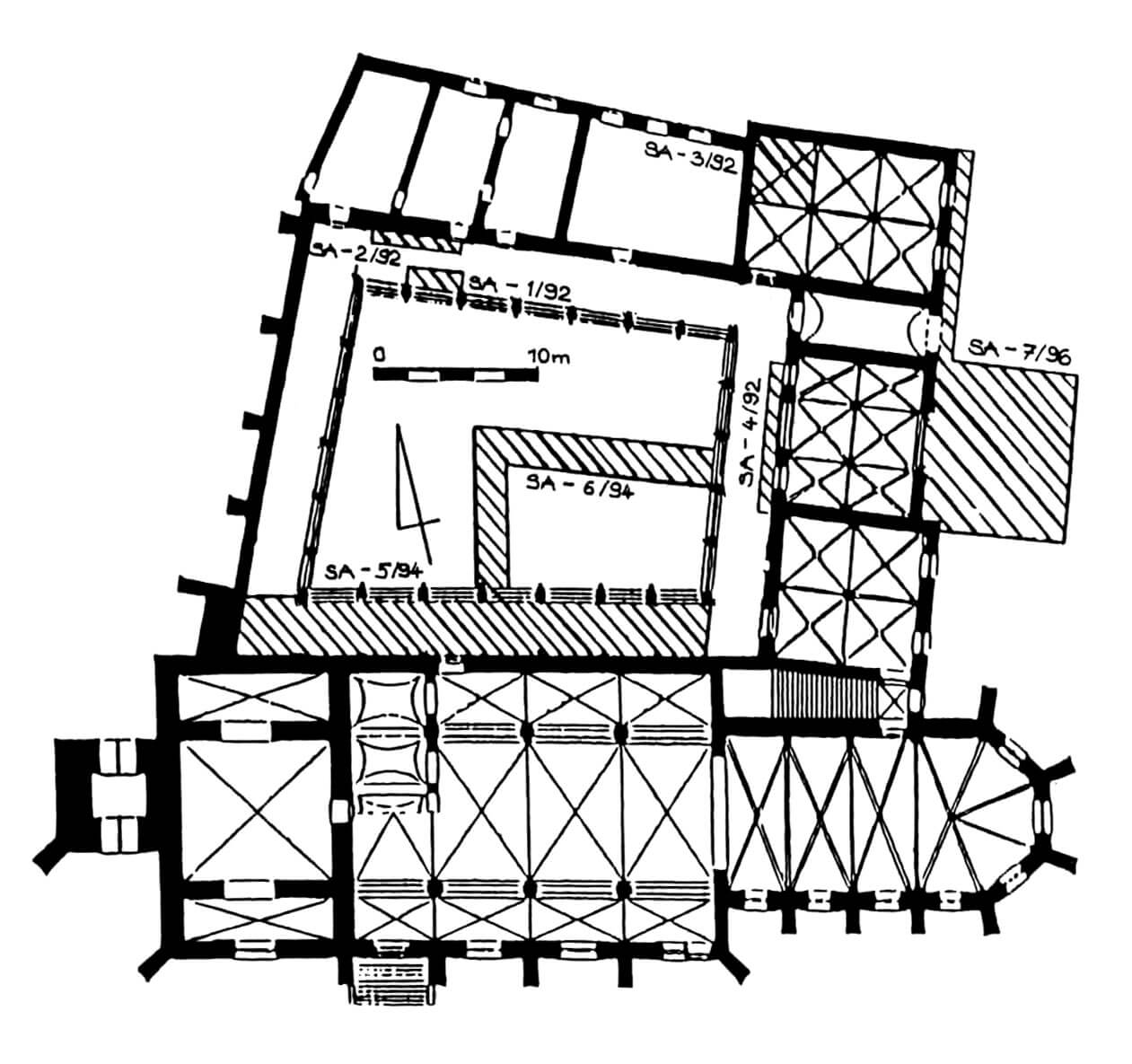

The friary was located in the western part of the chartered town, inside the town’s defensive walls. It was built in close proximity to them, but the underwall street on the western side of the monastic complex was made. The friary consisted of a church orientated towards the cardinal sides of the world and claustrum buildings on the north side. From the west, the church was adjacent to a four-sided tower with a passage in the ground floor, which provided access to the underwall street at the friary, to the economic area of the convent and clautrum rooms. A little further on the south side, there was a Polish Gate, giving access to the slopes descending towards the Levoča and Mill streams (after the gate was walled up in 1531, its name was transferred to the church tower). Within the town, the Franciscan plot formed the southern end of the last block of houses at the end of Monastery Street, where it opened onto a widened space leading to the Polish Gate and a short street connected to a junction with one of the main town roads.

The friary church was erected as a hall building with central nave and two aisles, with a strongly elongated, polygonal chancel in the east, typical of mendicant architecture. The whole from the south and east was enclosed with prominent stepped buttresses, between which ogival windows decorated with tracery were placed. In the chancel, slender two-light were pierced and three-light windows in a polygonal closure. In the nave from the south, there were usually four-light windows, but also one two-light window and an oculus with a rosette in the place where the height of the wall was limited by the entrance portal. The horizontal division of the façades was provided by a plinth, a drip cornice under the windows and cornices under the eaves of the roofs. A Gothic, moulded, stepped ogival portal, located from the south in the second bay from the west, led to the interior of the church from the south, as well as a more modest portal in the extreme eastern bay of the south aisle. The interior of the church was originally covered with colorful wall polychromes. The four-bay nave and three wide bays of the chancel were covered with cross-rib vaults. On the last, polygonal bay of the chancel two additional eastern ribs were added to the cross ribs.

The monastery buildings consisted of only two wings: north and east one, which, together with four-winged cloisters, surrounded the friary inner garth. On its western side, due to lack of space, there was only a cloister passage, behind which an underwall street ran, important for defensive reasons, because it provided the townspeople access to the town fortifications. The large difference in the height of the ground between the southern end of the eastern cloister and the western end of the southern cloister was solved by gradually lowering and correcting the level of the floor of both cloister passages with steps, which were also represented by the line of the plinth cornice of the church. In the 15th century, these differences were leveled during renovations with additional layers of mortar.

In the more important eastern wing, there was a refectory (dining room) in its northern part, separated by a passage from the chapter house, next to which there was a sacristy right next to the chancel of the church. This wing was two-story, with the upper floor roughly repeating the layout of the ground floor, thanks to which the internal passage was preserved as wide as the cloister. The rooms on the first floor have flat, wooden ceilings. Their unheated space were illuminated by windows from the east. On the south side, the eastern wing was connected to the church by a narrow room between the sacristy and the chancel, housing a staircase. The passage on the first floor probably ended behind the first bay of the southern cloister vault, with access to its attic and the attic above the western cloister, where the entrance to the claustrum was located on the ground floor.

The chapter hall, the most important room of the claustrum in which the entire convent met every day, was a two-aisle room with a cross-rib vault supported by two central, polygonal pillars with moulded plinths. On the eastern side, on the extension of the central bay, a small chapel with a three-sided closure and dimensions of 5.5 x 5.3 meters was protruded from the rectangular part of the chapter house. The ribs of the chapter house vault were springinf from the pillars without the use of consoles, gradually blending above the imposts. Corbels decorated with grooves were used in the corners of the hall and in the middle of its walls.

The sacristy was also covered with a cross-rib vault, but it was supported on a single central pillar with an octagonal cross-section. The springing of its vaults was created as a result of a continuous, cornice-free transition of narrow rib noses into the conical base of the corbels. These corbels were decorated with grooves on the vertical edges (which were the extension of the ribs), which was typical of older consoles from the last decades of the 13th century. In addition to the sacristy, the corbels were also grooved in the chapter house, the cloister and the chancel of the church, although the groovs covered there the entire surface of the corbels, not just the edges. At the intersections, the ribs were fastened with decorative mask-shaped and geometric bosses.

The refectory was covered, like the chapter house, with a cross vault based on two pillars. It formed the north-eastern corner of the friary, and its longitudinal axis on the east-west line was common to the northern wing. This location was intentional, because the northern wing, located for practical reasons on the less sunny side, served economic functions. It housed a kitchen, pantries and cellarium rooms. Located right next to the refectory, the kitchen was spacious, equipped with a hearth and a large chimney. The northern wing was directly connected to the water source and the waste pits on the outer courtyard. There, on the north side, there were stables and a fenced mill, which also played a defensive role as part of the town fortifications.

Current state

The Franciscan friary in Levoča is one of the best-preserved medieval mendicant convents in Slovakia, thanks to which it was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2009, as part of the Spiš Castle and monuments in its vicinity. Inside the church, polychromes from the mid-fourteenth and fifteenth centuries have been preserved, visible on the northern wall of the nave and in the sacristy. The nave vault was removed in 1694 due to the bad condition, but the vault in the chancel has survived. In the area of the former claustrum, the room of the chapter house, the sacristy and the cloister with relics of wall paintings, a Gothic wall niche and vaults are worth seeing. After the renovation in 2018, the friary was opened to the public.

bibliography:

Lukáč G., Stredoveký kláštor minoritov v Levoči. Predbežné výsledky archeologického výskumu v rokoch 1992-1996, „Východoslovenský pravek”, 5/1998.

Olejník V., Starý kláštor minoritov v Levoči, „Pamiatky a múzeá”, 3/2021.

Urbanová N., Starý kláštor minoritov v Levoči – novšie poznatky o jeho stavebnom vývoji [w:] Najnovšie poznatky z výskumov stredovekých pamiatok na Gotickej ceste II, red. M.Kalinová, Bratislava 2018.