History

Košice (Hungarian Kassa, German Kaschau) was founded in the first half of the 13th century by German settlers. Already the first known document from 1230 mentioning “villa Cassa” recorded a priest Gregor, who had a legitimate son, Šimon, which would mean that he came from the local Slavic inhabitants who did not yet know the obligation of celibacy, and not from Western European colonists. The aforementioned Gregor was officiating at the Romanesque, probably still small church called St. Michael or St. Nicholas. With the town charter granted by King Bela IV at the end of the first half of the 13th century, the settlement entered a period of rapid development. The growing population made the parish church was rebuilt, and in the third quarter of the thirteenth century, its dedication was changed to St. Elizabeth (“ecclesia sancte Elisabeth de Cassa”). The choice of the new call was influenced by the German environment, where Elizabeth died as a saint, and probably also by royal influence. In 1283 at the church of St. Elizabeth, a hospital for the poor was recorded, and in 1290 the Košice parish gained autonomy and was subordinated directly to the Bishop of Eger.

During the rule of Charles Robert and Louis the Great, Košice became one of the main urban centers of the northern part of Hungary. At the end of the 14th century, the townspeople took advantage of the prosperity, wealth and good relations with the royal court to build a Gothic, larger and more representative parish church, which was to replace the older building. A fire from 1380 could also have contributed to the construction of the Gothic church of St. Elizabeth, unless the information about it concerned the new church, because the papal document did not specify which church was destroyed. In addition, the decision to erect a new building was probably influenced by the so-called eucharistic miracle that happened in Košice around the middle of the 14th century, after which pilgrims and penitents began to come to the town. In addition to providing income, this movement gave Košice a spiritual primacy in the vast area of north-eastern medieval Hungary.

Beginning of construction of the church of St. Elizabeth probably began around 1390. King Sigismund of Luxemburg, Bishop of Eger, and especially wealthy townspeople with the town council were involved in this work. In addition, in 1392 and 1402, Pope Boniface IX issued bulls, thanks to which all pilgrims who contributed to the construction of the church had their sins forgiven, and the relic of Christ’s blood could be kept in the church. The first stage of construction work lasted until around 1420. During it, the perimeter walls of the nave and the first two floors of the western towers were erected. In the years 1420-1440, the octagonal superstructure of the Sigismund’s tower was made and the walls of the nave were raised. During this period, the remains of the old church of St. Michael, which was somehow enclosed with new walls, were finally demolished. In the years 1440-1462, the building was vaulted over the central nave, work on the chancel and sacristy was started, and the northern tower was completed. Subsequent works until the end of the 15th century were carried out under the supervision of master Stephen Lapicidus, also known as Stephen Staimecz from Košice. The aisles were then completed, in 1475 the chapel of the Holy Cross was built, in 1477 the chapel of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the chapel of St. Joseph on the north side at the end of the century.

In the years 1490-1491, Košice was besieged by Polish-Lithuanian troops, taking part in the fights for the Hungarian crown after the death of King Matthias Corvinus. Their shelling was supposed to have led to damage of the unfinished church. The temple was repaired at the end of the 15th century, under the supervision of Nicolas Krompholz of Nisa and Václav of Prague, with the financial support of King Ladislaus II of Hungary. The town also asked for help from Pope Alexander VI, who in a letter from 1494 allowed an indulgence. The influx of funds made possible repairs and the completion of the chancel by 1505. At that time, Juraj Satmári, the bishop of Oradea (Hungarian Nagyvárad), coming from Košice, conducted a mass in the church, although the last finishing works were to last for three more years (in one of the pillars a scroll with the date 1508 and the name of the master Krompholz was found).

Since the second half of the 16th century, the parish church of Košice often changed between Catholics and Protestants. In 1597, the Eger chapter moved to Košice, fleeing north after the fall of its original seat in battles with the Turks. Chapter did not have a strong position in the mostly Protestant city and often got into disputes with the townspeople, including over the affiliation of St. Elizabeth’s Church. In addition to religious conflicts, the condition of the church was worsened by natural disasters. Of these, the fire of 1556 was particularly severe, after which the city council hired Master Stanisław from Kraków, carpenters Juraj and Gabriel, and stonemason Matej to repairs. In 1682, after the capture of the city, Imre Thököli’s insurgents took the church from the Catholics and accused the chapter of mismanaging the property and causing the destruction of the church. Even greater damages to the building were caused by the fights with the insurgents of Ferenc II Rákóczi in 1706. Over the following years of the 18th century, various parts of the church were repaired, but greater interference in the architecture of the building was refrained from, even after the church was raised to the rank of a cathedral in 1804.

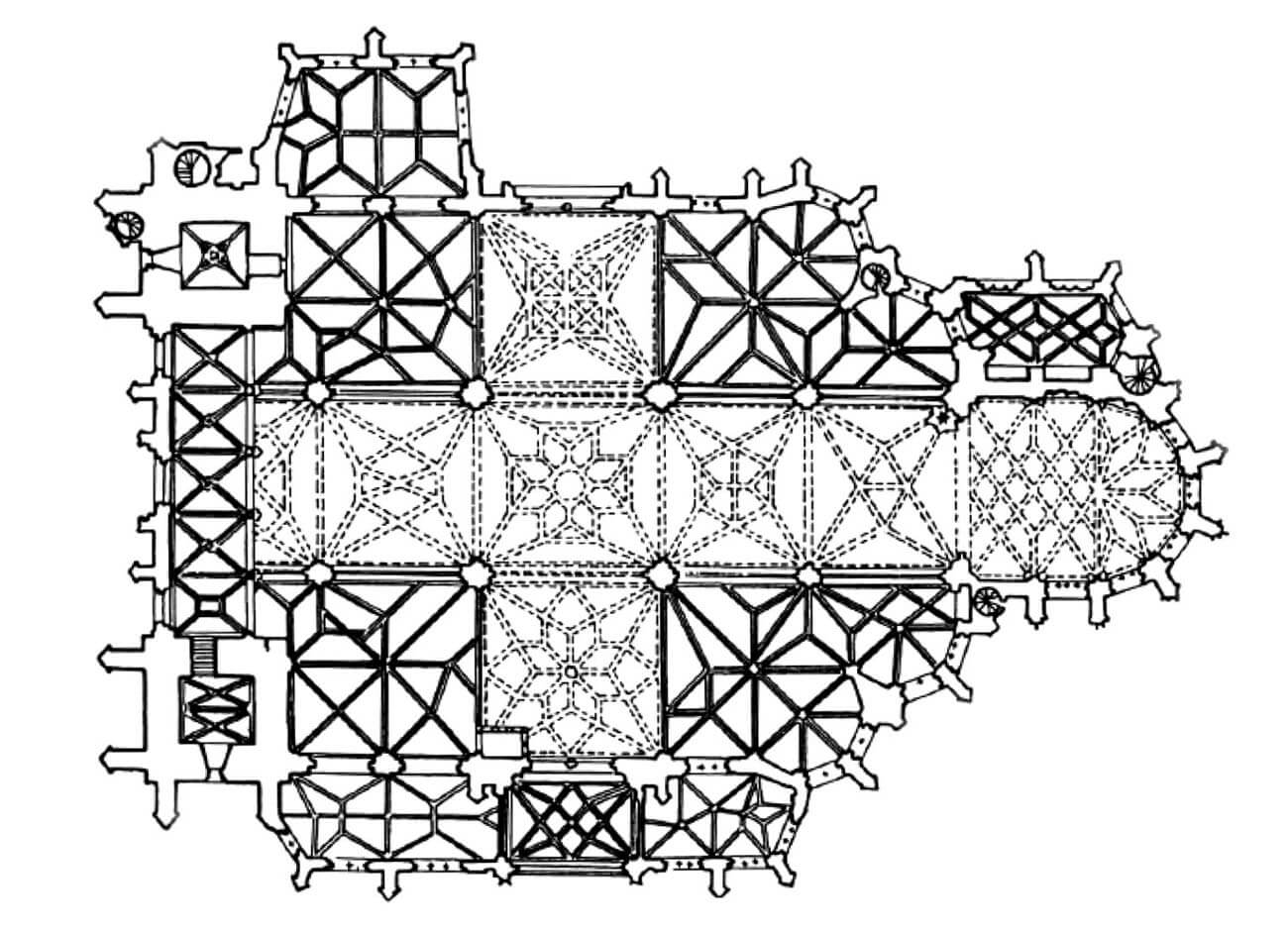

In the 19th century, the earthquake of 1834 and the flood of 1845 forced general repairs of the church to be carried out. The first works from the years 1858-1863 turned out to be so unprofessional that after several years and the storm of 1875, the monument again threatened to collapse. Only the renovation carried out in the years 1877-1896 turned out to be more permanent, but during it, among other things, the form of the church was changed from one pair of aisles to two pair of aisles, as it was considered that more pillars would improve the static properties of the building and prevent the vaults from cracking again. Extreme regothization also resulted in the demolition of the late-Gothic chapel of St. Joseph and the replacement of many architectural details. Only there were not enough funds to change the Baroque helmet of the northern tower. In 1970, the church of St. Elizabeth was declared a national cultural monument, thanks to which a few years later its comprehensive renovation work began.

Architecture

The church of St. Elizabeth was built in the southern part of the medieval town, in the middle of the main street running through Košice longitudinally, widened in area of the church to form a market square. From the south it was adjacent to the chapel of St. Michael, from the north to the town hall and commercial buildings. Originally it was a late Romanesque aisleless building, with a nave 27.8 meters long and 14 meters wide. On the eastern side there was a chancel measuring 11.5 x 10.2 meters, probably closed by a straight wall. From the west on the axis of the nave there was a quadrangular tower with an entrance portal in the ground floor, probably reinforced by lesenes in the corners. Both the nave and the chancel were clasped from the outside with buttresses, which would indicate that both parts of the church were vaulted.

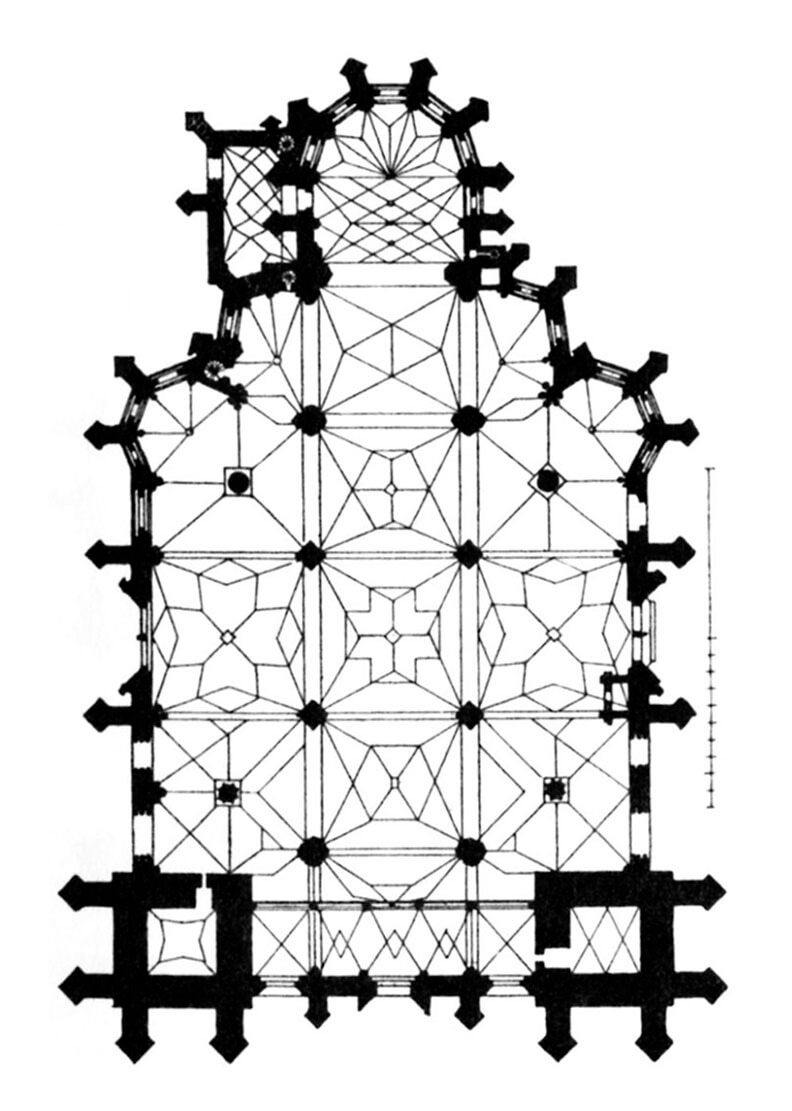

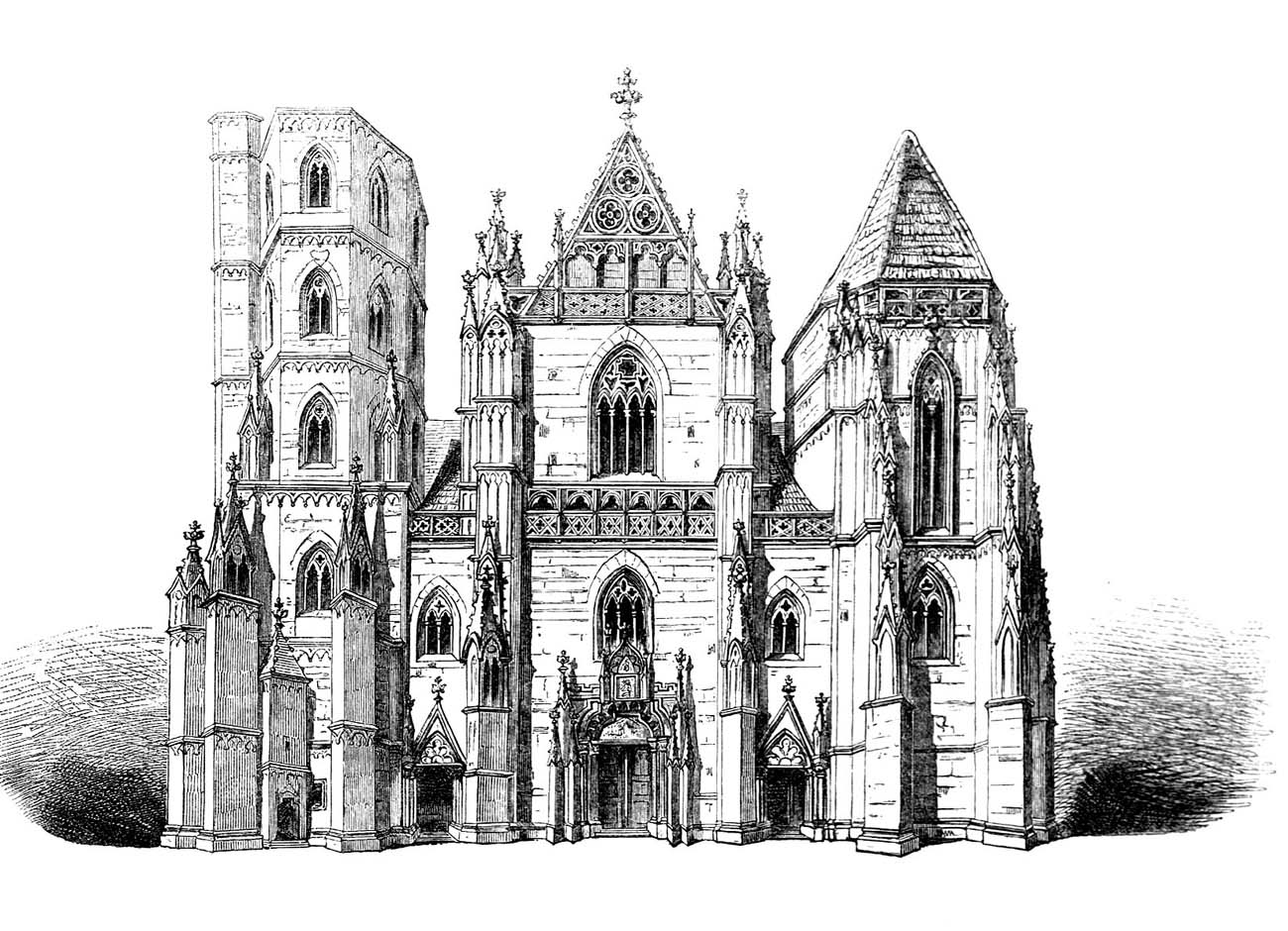

Church of St. Elizabeth was erected with a short central nave and two aisles, with a transept as wide as the nave and a relatively long, polygonal ended chancel on the eastern side. Polygonal closures had also the chapels on the sides of the chancel, while from the west the aisles were preceded by four-sided towers, of which the higher, northern one (called Sigismund Tower), above the third floor, was given an octagonal shape. The southern tower (called Matthew Tower) finally reached a height only equal to the nave and a four-sided shape at the level of all storeys. On the north side, a sacristy was placed next to the chancel. The walls of the church on the outside were fastened with stepped buttresses, which were topped with pinnacles. The next chapels were located on the south side of the nave. The entire church was approximately 60 meters long and 42.2 meters wide.

The lighting of the church was provided by a whole range of Gothic windows with moulded frames, from tall, three-light windows in the chancel, to shorter, two-, three- and four-light windows in the nave and towers. The walls of the church on the outside were framed with a plinth with a moulded cornice and stepped buttresses, which were decorated with blind tracery and topped with pinnacles adorned with numerous crockets and fleurons. The richness of the external facades was complemented by friezes and cornices under the eaves of the roofs, as well as balustrades filled with tracery, led along the edges of the roofs. Rainwater drainage was ensured by numerous gargoyles in the shapes of animals, monsters, fantastic beasts or grotesque figures. Particular attention was paid to both arms of the transept and the western façade of the central nave, on which the gables were preceded by openwork walls made of tracery motifs with intertwining quatrefoils, pointed and ogee arches, on which pinnacles and canopies with consoles for carved figures were placed. All façades of the church were characterized by splendor worthy of medieval cathedral buildings, from which the parish church in Košice differed in its more modest size and layout (e.g. lack of an ambulatory).

Several Gothic portals led to the interior of the church, the most magnificent of which was unusually embedded in the northern wall of the transept, due to its orientation towards the widest part of the market with the town hall and commercial buildings. This portal was divided into two passages filled with tracery in the upper parts, flanked and separated by rich moulding springing from the plinths, separated by canopies and consoles on which the figures were placed. The tympanum was filled with very numerous bas-relief figures of the Last Judgement, gathered in the upper band around Christ, and in the lower band divided into the damned in the monster’s mouth and the saved ones heading to the heavenly gate. The exceptionally elaborate archivolt with a stepped composition was divided into five quarters, each of which was framed by cornices, pinnacles or tracery and topped with a decorative battlement. The bas-relief scenes depicted the life of St. Elizabeth and the Crucifixion. The whole must have originally been covered with gilded decorations, because in the Middle Ages the northern portal was called the Golden Gate.

The western portal faced the street leading to the Clay Gate. For this reason, although it should normally be the main entrance and although it was decorated with a very rich set of details, it received a less monumental decor and composition than the northern portal. Its tympanum depicted Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, the apostles Peter, John and James, and the soldiers led by Judas. Above it was Mary holding the body of Jesus, surrounded by Mary Magdalene and Joseph. The tympanum was framed by moulded jambs of a two-armed form, on the sides of which were placed pinnacles decorated with crockets and topped with fleurons. The archivolt of the western portal, like the northern one, had a stepped form, but with one less step. It was topped with a decorative battlement, framed with pinnacles on the sides and filled with tracery decoration.

The southern portal, facing part of the cemetery with the chapel of St. Michael, was distinguished from the previous ones, as it was placed in the porch under the royal gallery. The high entrance to the porch was topped with a moulded ogee arch, with a fleuron in the finial and with a tracery motif of trefoils inscribed in semicircular arcades uder the arch. In front of the entrance to the porch in the Middle Ages there was a tower-shaped stone lantern of the dead, illuminating the entrance from the adjacent cemetery, quadrangular in the central part, set on a spirally twisted shaft and topped with a magnificent pinnacle with crockets and a fleuron. The interior of the porch was covered with a rib vault, creating a network from which four ribs were lowered to a protruding stalactite boss, similar to the southern entrance to St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. The portal in the porch itself was formed into two two-arm, moulded passages, each with a triangular wimperg and very rich tracery decoration. Additionally, two moulded pointed blind arcades were created above the wimpergs, connected with each other in the middle and with rounded arms on the sides, but divided by pinnacles added from the outside.

The interior of the church was originally spacious, divided into aisles with square bays, covered with stellar vaults, supported by massive, moulded pillars. The inter-nave arcades, similarly to the rood arch, received ogival forms, as well as moulding referring to the wall shafts of the vault lowered on the inter-nave pillars. In the chancel, a net and stellar – net vault was used, with ribs turning into wall shafts without the use of consoles. At the southern part of the transept a porch were placed, and above it a royal oratory. The entrance to it was placed in a Gothic spiral staircase, modeled on the communication turret from the Prague cathedral, built by the famous master Petr Parler. Its structure was created by an openwork composition of arcades with trefoil tracery inscribed in pointed arches. The stairs were made of two separate spindle-shaped flights with opposite directions of rotation, which were connected at each turn by several common steps (five times in total). The eastern stairs led to the oratory, while the western ones extended up to the transept vault, where led to the church’s attic.

An unusual element of the church interior architecture was a small but richly decorated balcony, suspended high at the level of the clerestory of the northern wall of the chancel. It was clearly not used very often, as access to it was quite inconvenient. From the northern side of the polygonal apse, the portal led up a narrow spiral staircase in the thickness of the wall, and then one had to go from the staircase in the attic to the entrance of the balcony. It received a tracery balustrade with a small bay protruding towards the south, with each corner decorated with a pinnacle set on a carved console. The whole was supported by a series of moulded cornices of increasingly shorter length, the penultimate of which was decorated with tracery.

In the 1470s, an exceptionally impressive pastophorium, a structure designed to store the Eucharist, was placed by the church’s chancel arcade. It had the form of a five-storey tower on a hexagonal plan, topped with a spire with a fleuron at the top. Its elevations were formed by an intricate composition of buttresses, cornices, pinnacles and arcades, among which a niche was placed on the second storey, closed on four sides with a decorative grate. Just below, the projection of the niche was accentuated by an openwork frieze of interlacing ogee arches, into which artfully carved plant motifs were woven. The buttresses at all levels were decorated with pinnacles and gables, with a large number of crockets and fleurons. Canopies and consoles supporting figures, originally representing the apostles and the Virgin Mary, were also placed on the larger pillars.

Current state

The Košice parish church, now the cathedral, is today one of the most valuable Gothic monuments in Slovakia and a symbol of the city. Apart from the Baroque helmet of the northern tower, it has a Gothic form, although the construction works from the 19th century introduced a number of significant changes. The most important was the transformation of the two aisles into four aisles. The vaults in the aisles were also changed, the late-Gothic chapel of St. Joseph was destroyed, a neo-Gothic turret was erected at the crossing and some pinnacles and gargoyles, which threatened to collapse, were removed. The cornices, pinnacles, window frames, tracery, gables and details of the entrance portals were renovated or replaced. In the 20th century, the crowns of the gables, gargoyles and other details of the architectural decor, due to the use of poor-quality sandstone in the 19th century, were renewed again or restored based on archival engravings. (among them there are original from the 15th century, such as a gargoyle in the shape of a bent-over woman with an ugly smile, hiding a bottle between her legs).

Inside the church, the western gallery is a completely neo-Gothic element, added in the 19th century on the site of a slightly shorter Gothic one, differing not only in dimensions and construction, but also in more elaborate decoration. Interestingly, the dismantled original gallery was bought by Count Johann Wilczek and used to rebuild the cloister at Kreuzenstein Castle near Vienna. In the church, however, the late Gothic tower-like pastophorium from the 1470s has survived, placed by the chancel arcade, attracting attention with its elaborate filigree and openwork decorations and its soaring, tall shape. Among the medieval furnishings, inside the church you can see also the Gothic main altar of St. Elizabeth from the years 1474-1477, a valuable work of medieval painting, composed of 48 painted scenes. Another very valuable monument is the Gothic Crucifixion group from around 1320, placed on the sill of the southern oratory. In addition, a bronze baptismal font from the first half of the 14th century has been preserved, one of the oldest surviving examples of foundry art in Slovakia, decorated with an inscription made in Gothic majuscule, the side altar of the southern aisle from 1516, or the late Gothic column with a canopy and a figure of the Virgin Mary. In the southern porch you can see one of the few lanterns of the dead in Slovakia, made in the 15th century.

The cathedral complex currently includes a free-standing bell tower of St. Urban, located on the market square on the north side of the church of St. Elizabeth. Contrary to older literature, it is an early modern building, erected after 1629, but 36 tombstones, mainly from the 14th-15th centuries, were built into its external facades. One of them is dated to the 4th century and is attributed to the origin of the Roman Empire.

bibliography:

Dom svätej Alžbety v Košiciach, red. I.Vaško, Košice 2000.

Hišem C., Aus der ältesten Kirchengeschichte von Kaschau, “Studia Elbląskie”, XXII/2021.

Krcho J., Rusnák R., K problematike datovania vývojových fáz Urbanovej veže v Košiciach, „Archæologia historica”, roč. 42, č. 1, 2017.

Lexikon stredovekých miest na Slovensku, red. Štefánik M., Lukačka J., Bratislava 2010.

Markušová K., Dóm sv. Alžbety. Sprievodca po košických kostoloch, Košice 1998.

Zubko P., Kult Svätej Krvi v Košiciach, Košice 2013.