History

According to written sources, the monastery was founded in 1075 by the Hungarian king Géza II in order to colonize the Hron valley, then densely forested and devoid of larger human settlements, and to support Christianity. The discovery of valuable deposits of gold and other minerals in the surrounding mountains soon attracted numerous colonists, who founded a settlement under the monastery, in 1217 gifted with the town privilege by Andrew II. Due to its strategic location, there were also numerous defensive hilllforts in the vicinity of the monastery (e.g. Beňadická Skala).

The process of founding the abbey was long, probably started when Géza was the prince of Nitra. In a document from 1075, the monastery church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Benedict had already served as a topographical point, so it must have been in an advanced state of construction. The property of the monastery, already large since its foundation, was increased by new donations in the 12th century. Among others, in 1157-1158, Stefan, son of Adrian, having no descendants, gave his property to the monks with the king’s consent, and in 1165 for the same reason a certain Farkaš gave them his goods in Slepčany and Ebedec. According to the data contained in the list of papal tithes from 1332, the abbey was then one of the richest religious houses in the kingdom. Increased income made it possible to build a magnificent Gothic basilica in the years 1346 – 1375 on the site of the original Romanesque monastery church and expand the original claustrum.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the abbey had to be damaged by fire, because in 1405 Pope Innocent VII sought help in its reconstruction. These works lasted intermittently until the beginning of the 16th century. However, already in 1528 the monks left Hronský Beňadik due to the Turkish attacks. Under the Muslim thread, in the 1530s, the rebuilding of the monastery into a fortress began. Defensive walls and artillery towers to the sacral buildings were added, while strengthening of the defensive function resulted in the destruction or transformation of several Gothic buildings. The last major transformations were introduced as part of the alterations made at the end of the 19th century, during the reconstruction after the great fire of 1881. The archaeological works accompanying the renovation were the first intentional archaeological research of sacral architecture in the territory of today’s Slovakia.

Architecture

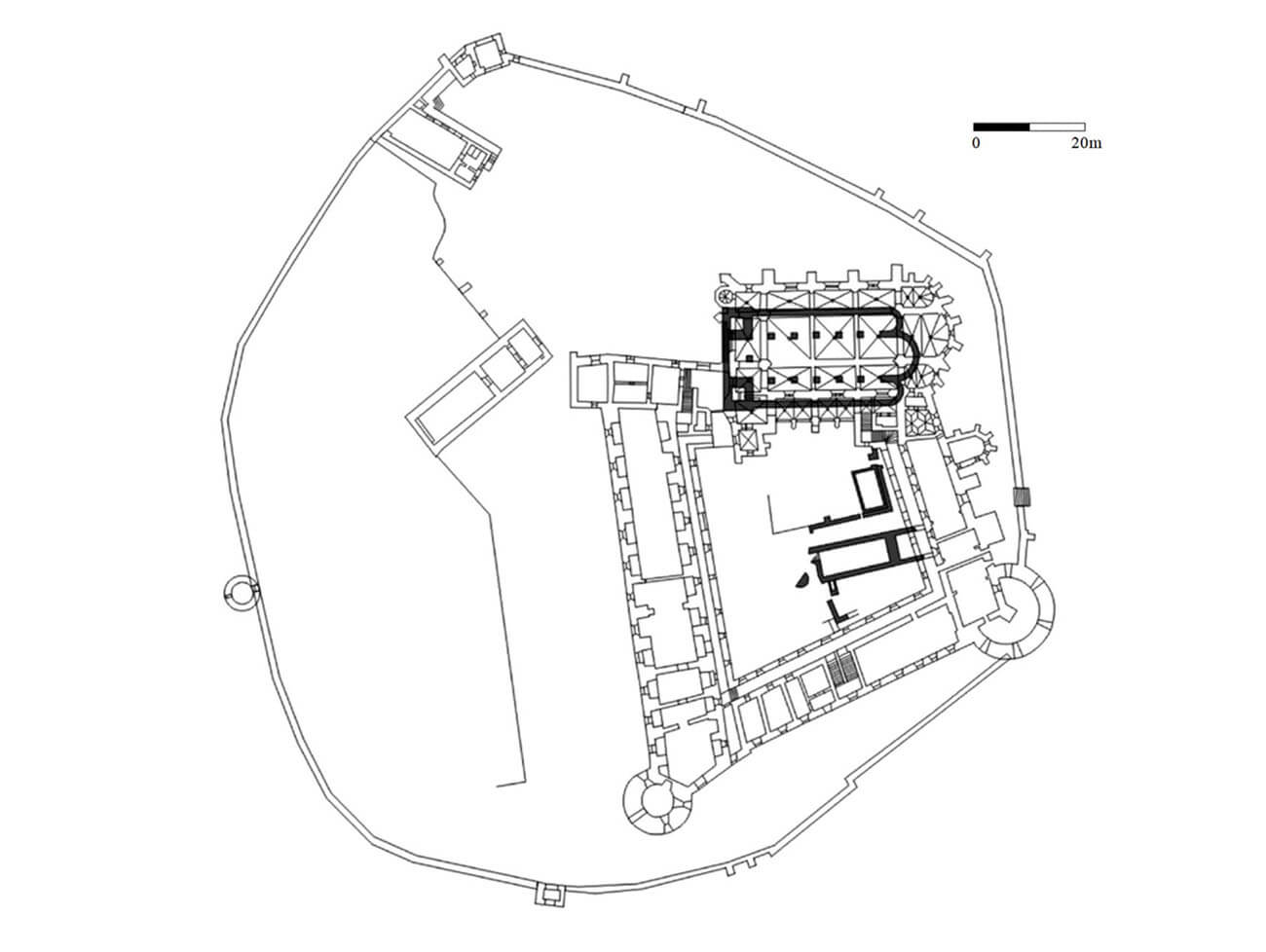

The abbey was built on a promontory of a hill overlooking the valley of the Hron River. The river bed was adjacent to the monastery from the east, in the north the slopes of the hill descended into a short gorge separating the two hills, while in the south the area increased towards the top of the monastery hill. In the early Middle Ages, the surrounding areas were covered with dense forests, and the unregulated river could flood the valley.

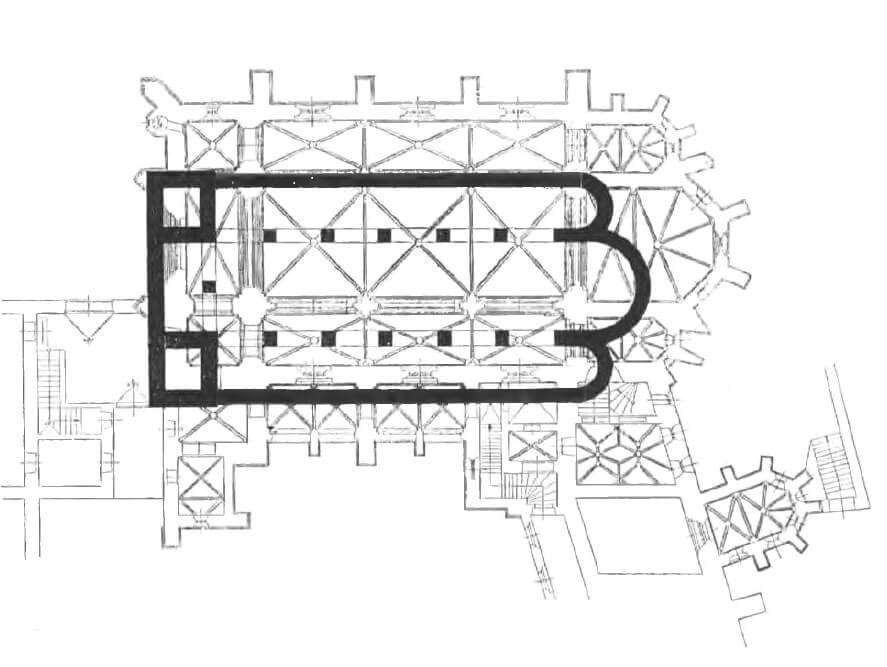

The first stone church was a Romanesque basilica with three aisles, without a separated externally chancel, ended in the east with semicircular apses: one large closing the central nave and two smaller ones at the end of the side aisles. They were all situated at one height. On the opposite, west side, the façade was formed by two four-sided towers. Inside, the six-bay central nave was twice as wide as the aisles and opened to them with arcades based on four-sided pillars. On the other hand, the towers in the ground floor had full walls, not opening with arcades neither to the inter-tower porch nor to the side aisles (a feature characteristic of the second half of the 12th century). Perhaps there was a gallery between the towers.

On the southern side of the Romanesque church, there were the oldest claustrum, in the form of a closed buildings with a small courtyard of an irregular trapezoid shape, around which the passages of the cloisters ran. The wings of the monastery buildings were connected to them at least from the east and south. The abbey also had to have economic buildings, initially probably of wooden or half-timbered construction. The configuration of the terrain allowed them to be placed on the south or west side.

The Gothic basilica also received the form of a three-aisle structure, shifted a bit more to the north than the older temple and a bit longer. The west façade was again made up of two four-sided towers, although more massive, and from the outside, the chancel was not separated from the nave, which in the east was located in three, already Gothic, polygonal ended apses: again larger on the extension of the central nave and smaller at the end of the aisles. Inside the church, a layout was used with three square-like bays in the central nave (as well as one rectangular bay between the towers) and three rectangular bays in each of the aisles, all of which were topped with cross-rib vaults. The eastern apses were equipped with single rectangular bays covered with cross vaults and polygonal closures with six-section vaults. The entire church, except on the south side, where there was a cloister, was reinforced with buttresses. From the south, a late-Gothic chapel of Holy Blood was attached to the church in 1489.

The monastery complex was built on an irregular quadrilateral plan. The courtyard was surrounded by cloisters with rib vaults, around which there were buildings of the enclosure and the church of the Virgin Mary and St. Benedict. The southern and eastern wings of the monastery were mainly residential and representative. According to the Benedictine pattern, the eastern wing housed, among others, the chapter house in the ground floor and the dormitory on the first floor, and the refectory in the southern wing. The latter was heated by a hypocaustum stove placed in the basement, replaced by a tiled stove in the 15th century. In the western part, there were warehouses and pantries as well as lay brothers’ rooms, and the northern side was closed by the church.

Due to the reconstruction from the 16th century, the area of the monastery increased about three times and was reinforced with massive, cylindrical cannon towers or bastions. Additional protection was provided by the defensive wall, which in the 16th century was raised, thickened and equipped with platforms for shooters. This wall was connected with the south-eastern bastion, which was the corner of the claustrym buildings. In addition, the perimeter wall was reinforced with smaller towers: four-sided on the south side and cylindrical one on the west side. The entrance led through the gatehouse from the north.

Current state

The monastery church and the buildings of the Hronský Beňadik Abbey, despite early modern transformations, largely retained their form from the time of the Gothic expansion. What’s more, in their area there are probably some of the key monuments of stone sacral architecture of the 11th century, of great importance not only in today’s Slovakia, but also in the context of medieval Hungary. From the Gothic era, the pride of the abbey is the monumental western portal of the church from the third quarter of the 14th century, supplemented with neo-Gothic figures from the 19th-century renovation. Inside, vaults with a richly decorated support system, a Gothic niche with an original iron grille, and fragments of wall paintings from the early 15th century have been preserved.

Entrance to the monastery walls is possible, however, the object is not suitable for sightseeing. The interior of the church can be seen only in July and August, and in other periods after prior telephone notification. There is also available a courtyard and a part of the preserved Gothic cloisters.

bibliography:

Hanuš M., Teplovzdušné vykurovanie v stredoveku na území Slovenska, “Slovenská archeológia”, LXIX/1, 2021.

Mencl V., Stredoveká architektúra na Slovensku, Praha 1937.

Podolinský Š., Gotické kostoly, Bratislava 2010.

Pomfyová B., Ranostredoveké kláštory na Slovensku: torzálna architektúra – torzálne poznatky – torzálne hypotézy, „Archæologia historica”, roč. 40, č. 2, 2015.

Wasielewski A., Zamki i zamczyska Słowacji, Białystok 2008.