History

Divín Castle was built at the end of the 13th or beginning of the 14th century, probably from the foundation of the Lossonczy (Lučenec) family. The initiator of the building could have been Dionýz of Lučenec, recorded in documents in the years 1275-1294, or his sons Tomáš, Štefan and Dezső. The castle was first mentioned in document in 1329, eight years after the death of Máté Csák (Matúš Čák), a magnate who rebelled against the Hungarian king and who may have captured Divín. During the fighting, the building must have been burned down, because in the second quarter of the 14th century, renovation works at the castle were carried out by Tomáš, who was the only brother to settle in Divín and bought shares in this part of the family estate from the rest of the siblings.

For the second half of the 14th century, the castle was the collective property of the Lossonczy family, which was confirmed by the division in 1393, made after the death of the Croatian-Slavonian-Dalmatian ban Dionysius of Lučenec, son of Tomás of Lučenec. At that time, Divin represented only a peripheral part of the family estate, concentrated primarily in Transylvania. During the period of unrest and internal struggles in the first half of the 15th century, the castle was probably not besieged, although a band of post-Hussites troops occupied the nearby castle of Ozdín in 1460. Due to the Lossonczys’ participation in the rebellion of the Transylvanian Prince Jan Groff, King Matthias Corvinus donated part of the castle estate to Palatine Michal Országh in 1467. However, Országh did not actually take possession of the castle, which, together with another, unconfiscated part of the estate, was given by Michal Dezsőfi from the Lossonczy family to Jan Nádasdy Ongor, one of the leading figures at the royal court. Jan and his two sons attempted to gather the entire Divín estate, but the siblings had no male heirs. When Jan Ongor died in 1506, he left a widow, Dorota from Poroszló, and an unmarried daughter, Katarína. Michal from Szob, the župán of Hont, took advantage of this situation and captured the castle. Eventually, a compromise was reached, under which Katarína received Divín and was married to Ferenc Balassa, indicated by Michal from Szob.

In the first half of the 16th century, Divín began to be threatened by Turkish expansion, especially since the castle’s fortifications were outdated and underdeveloped. In the turbulent times after the Battle of Mohács, in which Katarina’s father-in-law was killed, the Balass family sided with Jan Zapolya in the conflict with the Habsburgs. This was probably why, when Katarína died childless before 1535, Ferdinand I Habsburg recognized Divín as his property and formally transferred it to the Archbishop of Esztergom. However, the Balass family had no intention of giving up their extensive estates on the border with their main seat in Modrý Kameň. Moreover, after the capture of Fiľakovo by the Turks in 1554, they began to expand and strengthen the fortifications of Divín. Despite this, the castle was captured by the Ottomans in 1575, becoming one of their northernmost outposts. For this reason, in the following years, the Turks made Divín a base for plundering expeditions into the surrounding areas. The castle returned to the Balassa family after a successful siege in 1593. At that time, it was in poor condition, and what is more, the inhabitants of the castle estate were still serving the Ottomans.

In the second half of the 17th century, Divín was owned by Imrich Balassa, famous for raiding and plundering the surrounding villages. In order to bring him to court, in 1666 the castle was besieged by the troops of Palatine Ferenc Wesselényi. Seeing no chance of effective defense, the castle garrison handed Imrich over, but he was soon released thanks to connections and bribes, and settled in the fortified court house below the castle. What’s more, he defeated the imperial garrison and reoccupied his main seat. During the anti-Habsburg uprising of Imrich Thököly, in 1674 there was a six-week, unsuccessful siege of the castle by imperial troops. Another siege in 1683, this time finally ended with the capture and destruction of the castle. It was later given to the Zichy family, but was never rebuilt.

Architecture

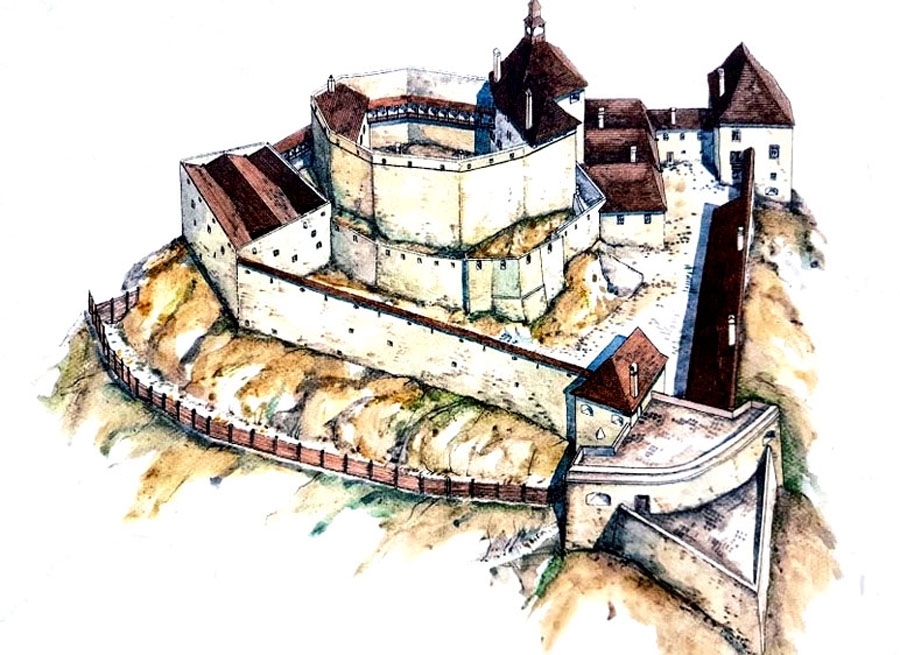

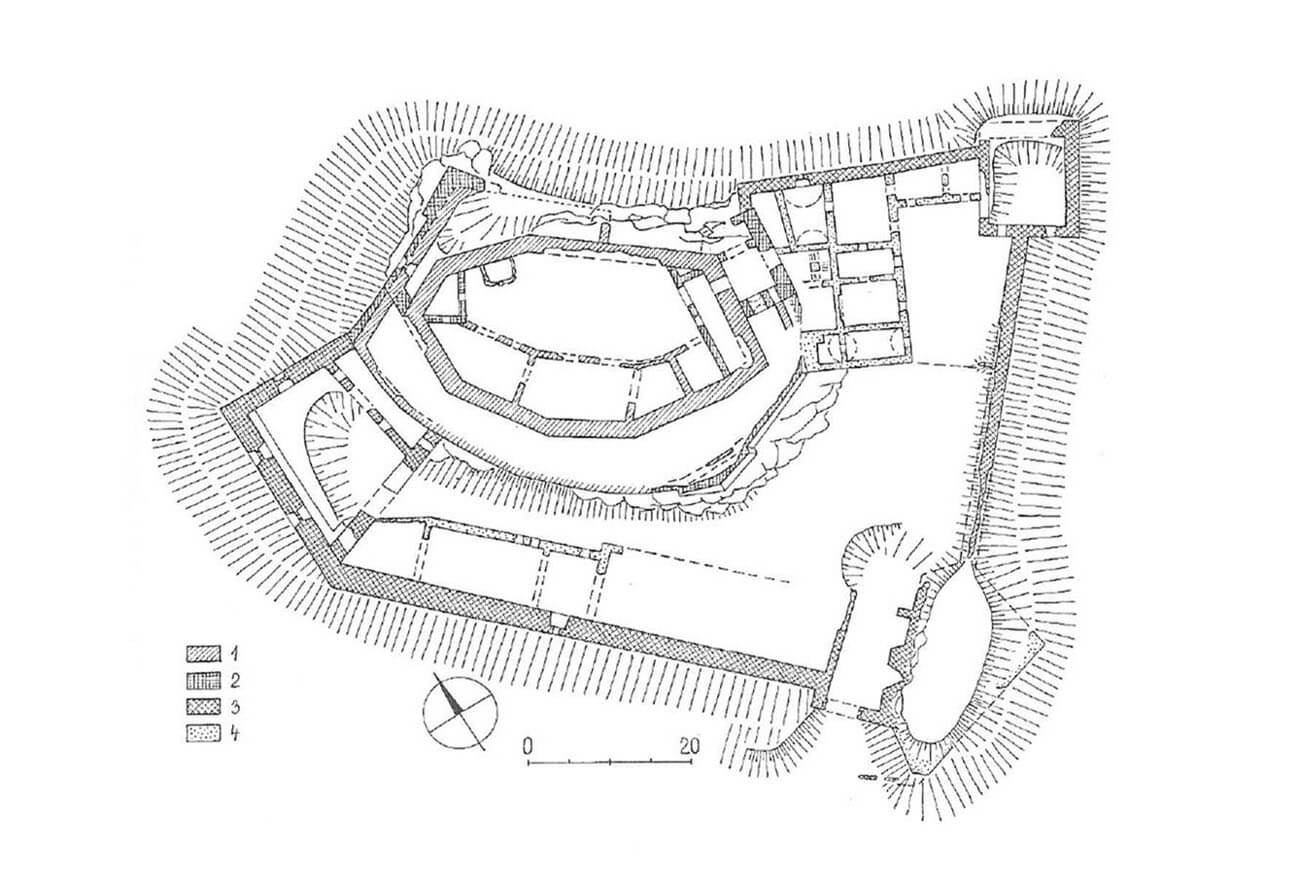

The castle was situated on a relatively high, rocky hill, south of the settlement of Divín. On all sides the building was well protected by slopes, which were only slightly gentler on the south, due to the proximity of a narrow pass separating the castle hill from the rest of the mountain range. From the north, the slopes were the highest and steepest, but access was also significantly difficult from the west and east.

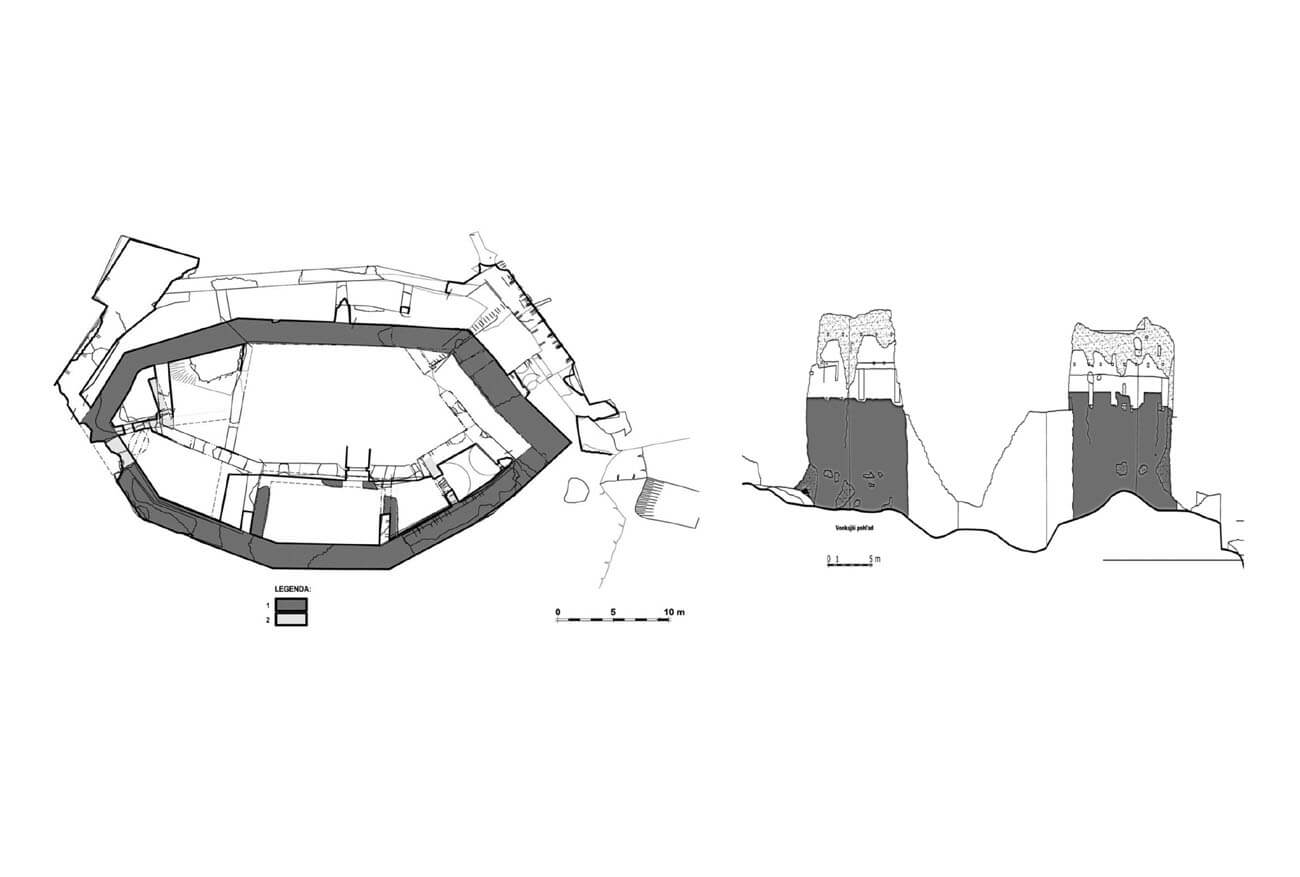

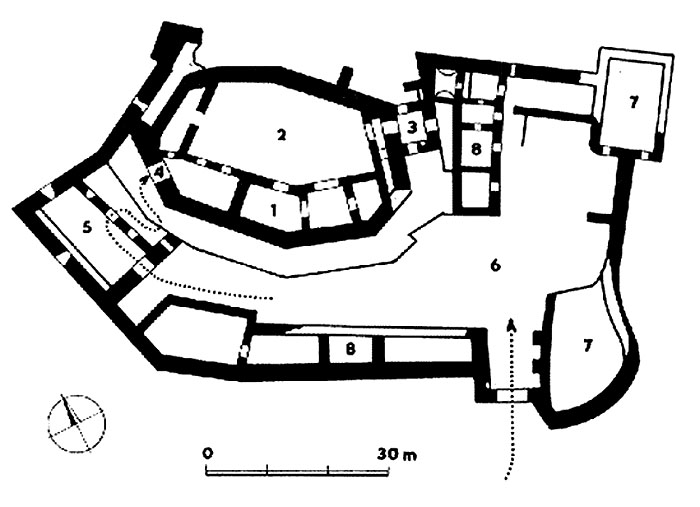

The oldest part of the castle had a shape close to an oval measuring 44 x 25 meters, created by short and straight sections of the peripheral defensive wall, running along the edges of the slopes. Its thickness was significant, reaching up to 2.4-2.7 meters, which allowed the construction of a wall-walk and battlements in the crown. The height of the wall oscillated around 11 meters. In the southern part of the courtyard, a residential building with three rooms at ground level was attached to the defensive wall, probably not higher than the crown of the wall. The water supply was provided by a reservoir carved into the rock in the northern part of the courtyard, while the entrance gate was located in the western part. Due to the slope of the terrain, it was accessible via a wooden ramp. The castle in its oldest form was a towerless structure typical of Moravia, but also found in Silesia and the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its defense was based on a strong perimeter wall and natural conditions of the terrain.

The reconstruction of the castle after the destruction in the first half of the 14th century resulted in the original residential building being replaced by a new building located near the north-western section of the defensive wall. Its construction involved bricking up the original entrance gate and significantly enlarging the courtyard area. The new entrance was created in the eastern part of the perimeter, where it may have already been protected by a quadrangular tower or gatehouse, preceded by a wooden bridge set on a brick pillar. Perhaps the relocation of the residential building resulted from the unusual location of the first building, placed next to the gate, not opposite it, and at the same time on the side where the slopes of the hill were the gentlest.

Around the middle of the 15th century, the old residential building was replaced by a late Gothic residential wing with a basement, stretching along the defensive wall in the southern and south-eastern parts of the courtyard. In addition, the castle fortifications were extended by the perimeter of the external defensive wall, which repeated the layout of the main wall. The created zwinger, about 5 meters wide, was used to lead the entrance road, leading from the outer gate in the west to the main gate in the east. The latter, at the latest during the late Gothic expansion, was preceded by a gatehouse, completely protruding in front of the perimeter of the main walls and connected to the new wing on the side of the courtyard.

Despite the late Gothic expansion, Divín remained a small knight’s castle with simple fortifications until the end of the Middle Ages. The area to the east and south of its core was used for the economic buildings of the outer bailey since the 14th century. The fortifications there were for a long time of wood and earth. It were replaced by a massive 3-meter-thick stone wall only during the 16th century rebuilding. During this expansion, three buildings were also erected on the outer bailey: a quadrangular building with a form similar to a tower in the eastern corner, a gatehouse on the southern side and an extensive western building, which filled the corner at the entrance from the outer bailey to the inter-wall zwinger.

Current state

The castle has been preserved in the form of a ruin, with the massive wall marking the oldest part of the castle not affected by all later reconstructions. Some of its sections have survived to this day in their original height, on some parts, the superstructures of the crown from the 16th and 17th centuries are also visible. The 15th century external wall of the zwinger has been preserved in a much worse condition, while the massive 16th century wall protecting the outer bailey is almost entirely visible from the front of the castle. Early modern transformations from the 17th century affected primarily the now ruined residential buildings and the area of the outer bailey. The ruins of the building under the gate of the upper ward and the south-eastern bastion come from this period. The castle is open to visitors.

bibliography:

Bóna M., Plaček M., Encyklopedie slovenských hradů, Praha 2007.

Fottová E., Janura T., Šimkovic M., Hrad Divín vo svetle nových výskumov, “Acta historica Neosoliensia”, 23/2020.

Wasielewski A., Zamki i zamczyska Słowacji, Białystok 2008.