History

The Premonstratensian monastery, together with the church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, was built in the late 12th or early 13th century, founded by Comes Omodej, before he set out on a crusade alongside King Andrew II in 1217 or 1218. It was first recorded in written sources in 1273, in a document containing the last will of the deceased Magister Stefan, a member of the Hunt-Poznan (Hont-Pázmány) family, who was to be buried in the church in Bíňa and which confirmed the donation made to the monastery by his father Omodej. This donation was most likely transferred to an already functioning monastery.

At the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, at least some stonecutters worked on the construction of the monastery, taking part in the reconstruction of the cathedral and the royal and archbishop’s residence in Esztergom. Works in Bíňa probably lasted until the end of the second decade of the 13th century, being in its final stage at the time of the founder’s crusade. Omodej’s descendants kept the patronage over the monastery and church probably throughout the Middle Ages. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the surrounding lands and the abandoned monastery were under the rule of the Turks, with the Premonstratensians leaving Bíňa already in the 16th century. The monastery complex was captured in 1683 by Polish troops returning from Vienna, which led to the destruction of most of the buildings.

The renovation of the church itself took place in 1722-1732, when the nave and the vestibule were vaulted again. During it, the Baroque reconstruction of the temple was carried out (transformed windows in the nave, porch and side chapels, building the southern sacristy), and in the years 1861-1862 another modernization took place, unfortunately carried out in a rather arbitrary way. It caused so much opposition that in the years 1895-1898, further renovation works were carried out, this time in the neo-Romanesque style. The building was severely damaged during World War II. The explosion destroyed the vestibule (porch), almost the entire north tower and the upper part of the south tower, as well as the nave’s roof. Fortunately, in the years 1951-1955 a comprehensive reconstruction of the monument took place, combined with architectural research.

Architecture

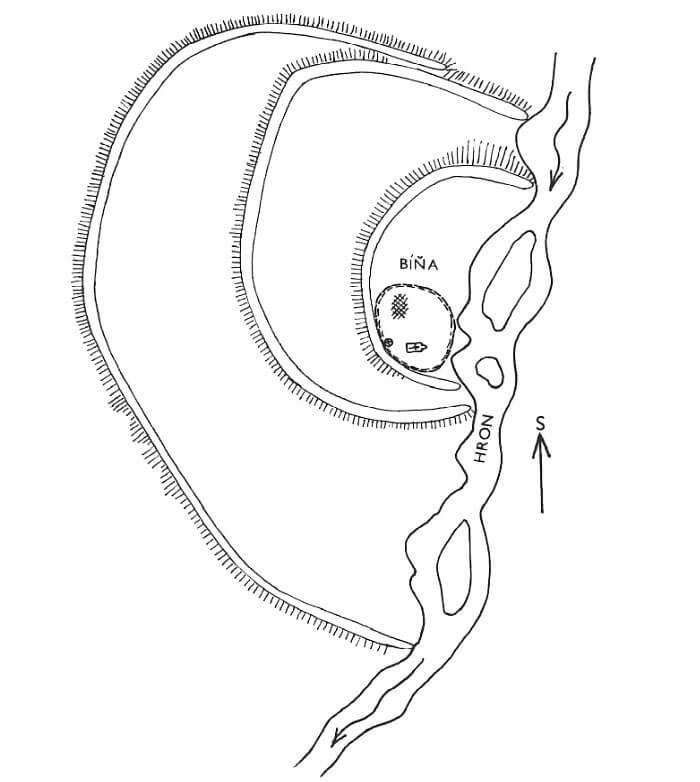

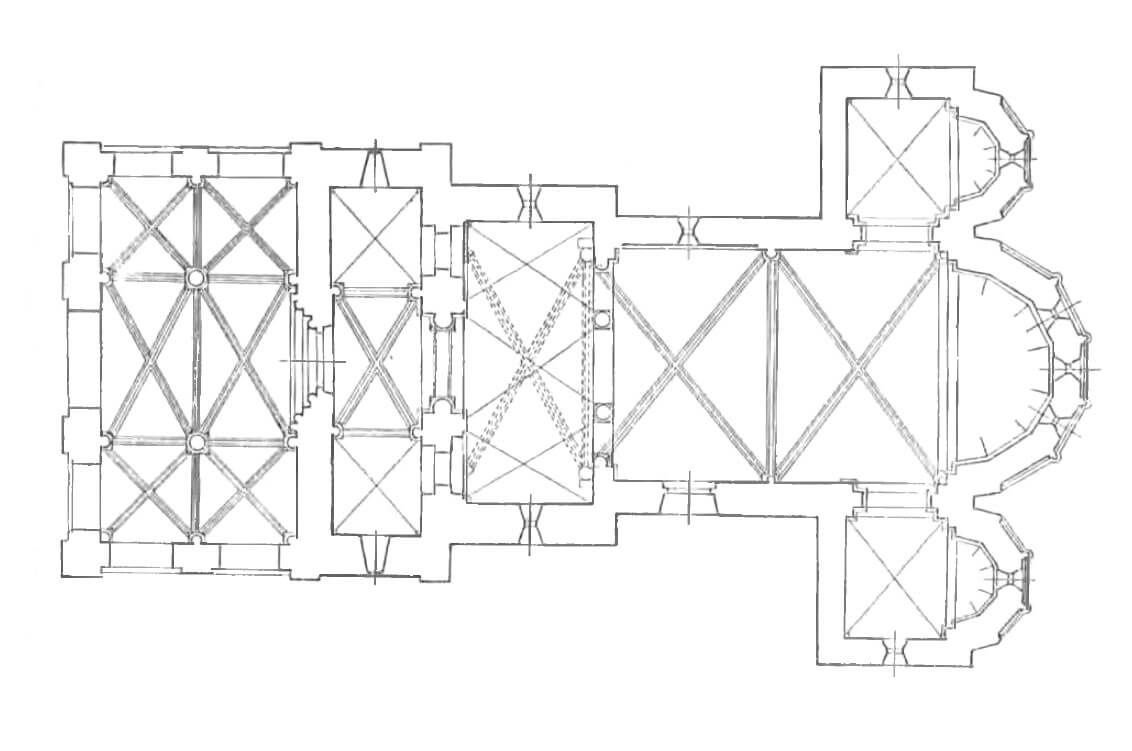

The church was built on a riverside slope on the west bank of the Hron River, as a single-nave structure with two towers in the west elevation, mistakenly giving the impression of a basilica behind them, and a large, originally one-storey porch added to the facade. The west façade originally had a large rosette window (later obscured by the addition of an early modern porch upper floor). From the east, a rectangular chancel was erected with a central apse and two smaller ones from the north and south, added to the side single-bay chapels, similar in plan to the transept with the appearance of a trident. The central apse has seven sides, the side ones are pentagonal. Their external façades were divided by blind arcades, and the lighting was provided by relatively high windows (three in the main apse, one on the every side apse). Additionally, the middle apse was decorated with an arcaded frieze.

The impressive west porch was erected during the construction of the church from the same stone ashlar. Originally, on the sides of the entrance portal, located on the axis of the west façade, it housed two (one on each side) large, semicircular, stepped arcades with side impost cornices. Further such arcades were located in the side walls of the porch from the north and south. As the gallery was illuminated by the aforementioned round rosette, the porch had to be one-story. Its interior was covered with a vault based on two pillars, dividing the vestibule into three short aisles, two bays long. This could be matched by a three gable roofs. Inside, the porch housed the main entrance portal to the church with a semicircular archivolt decorated with shafts and steps and with columns inserted into the steps on the sides of the passage. The columns were equipped with capitals with floral and figural decorations in the form of an atlant or a praying man with raised hands.

The church is unique because of its proportions, because the western part with the porch, towers and internal gallery is longer than the nave with the apse. What’s more, the gallery (matroneum) is a kind of transition between the two-tower front and the nave. The gallery also had an extension in the form of a tribune, occupying the entire western span of the nave. Gallery was probably connected by small portals with floors of the towers, it also had two semicircular altar niches, symmetrically placed in the thickness of the walls, constituting the base of the arcade, which the gallery opened onto the nave. The inter-tower part was crowned with a cross-ribbed vault.

The main task of the magnificent western part of the church was to declare the prestige of the founder’s family and the functions related to the representation of lay patrons and liturgical care over their souls. In contrast, the space reserved for lay visitors to the church or for the monastery’s economic workers (lay brothers) has been reduced to a relatively short section of the nave. The eastern part of the church, as part of the monastery enclosure, was available only to monks. The side chapels, open to the choir with arcades, met the liturgical needs of the monastery. There were side altars, necessary due to the requirement of the Premonstratensian regulations regarding private funeral masses, which were not allowed to be sung in the choir at the main altar. In addition, above the chapels of the church there were originally attic spaces resembling galleries, perhaps also used as stands for singers.

From the south, the monastery buildings were adjacent to the church, grouped in a traditional arrangement with a rectangular courtyard in the middle surrounded by cloisters. The west wing was in direct contact with the porch and was two or three-space at the gorund floor. In the south-east corner it was adjacent to the south wing. On the western side of the church there was a rotunda dedicated to the Twelve Apostles. The entire monastery complex was located inside extensive earth fortifications from the 9th/10th century, formed by three concentric ramparts.

bibliography:

Mencl V., Stredoveká architektúra na Slovensku, Praha 1937.

Pomfyová B., Ranostredoveké kláštory na Slovensku: torzálna architektúra – torzálne poznatky – torzálne hypotézy, „Archæologia historica”, 40/2015.

Pomfyová B., Samuel M., Žažová H., Stredoveká sakrálna architektúra v Bíni (sumarizácia, korekcia a doplnenie súčasných poznatkov), “Archaeologia historica”, vol. 38, 2013.

Szénassy A., Lexikon románskych kostolov na Slovensku. 1 zväzok, kraj Nitra, Komárno, 2005.

Tomaszewski A., Romańskie kościoły z emporami zachodnimi na obszarze Polski, Czech i Węgier, Wrocław 1974.