History

The founders of the monastery were Cistercians from Oliwa, who received Żarnowiec from Pomeranian dukes around 1215. The foundation took place a few decades later, certainly before 1245, because then the protective bull of Pope Innocent IV took care of the monastery in Oliwa and all his possessions, including “the lake next to the seat of nuns”. The files of the Oliwa Abbey show that in 1267 there was already a convent in “Sarnowitz”. Officially, the monastery was approved by the reigning prince Mestwin II in 1279. In 1283, in documents brother Gerlach, provost of nuns, was recorded.

From the very beginning, the new monastery was completely subordinated to the abbey in Oliwa, both in terms of church and administration. This relationship was unique among Polish Cistercian convents, perhaps influenced by the prohibition on establishing female monasteries, issued by the general chapter of the order in 1228. Probably the Oliwa Cistercians obtained special permission from the Pope for the foundation and thus took complete power over it. Instead, they had to take care of the cistern sisters, e.g. through numerous grants, including already developed villages. In addition, the nuns had the surrounding forests, Lake Żarnowieckie, the Piaśnica River on the section from the lake to the sea and part of the sea shore itself. On the other hand, the prince gave the cistercians special judicial and economic privileges.

The monastery had a farm (grange), in which lay sisters worked, i.e. uneducated nuns who did not make full vows. To the farm belonged rather poor arable land where rye and oats were grown. Probably, a sheep farm was also developed, that provided the wool needed for sisters clothing. Mills, foils and a brewery also worked for the monastery.

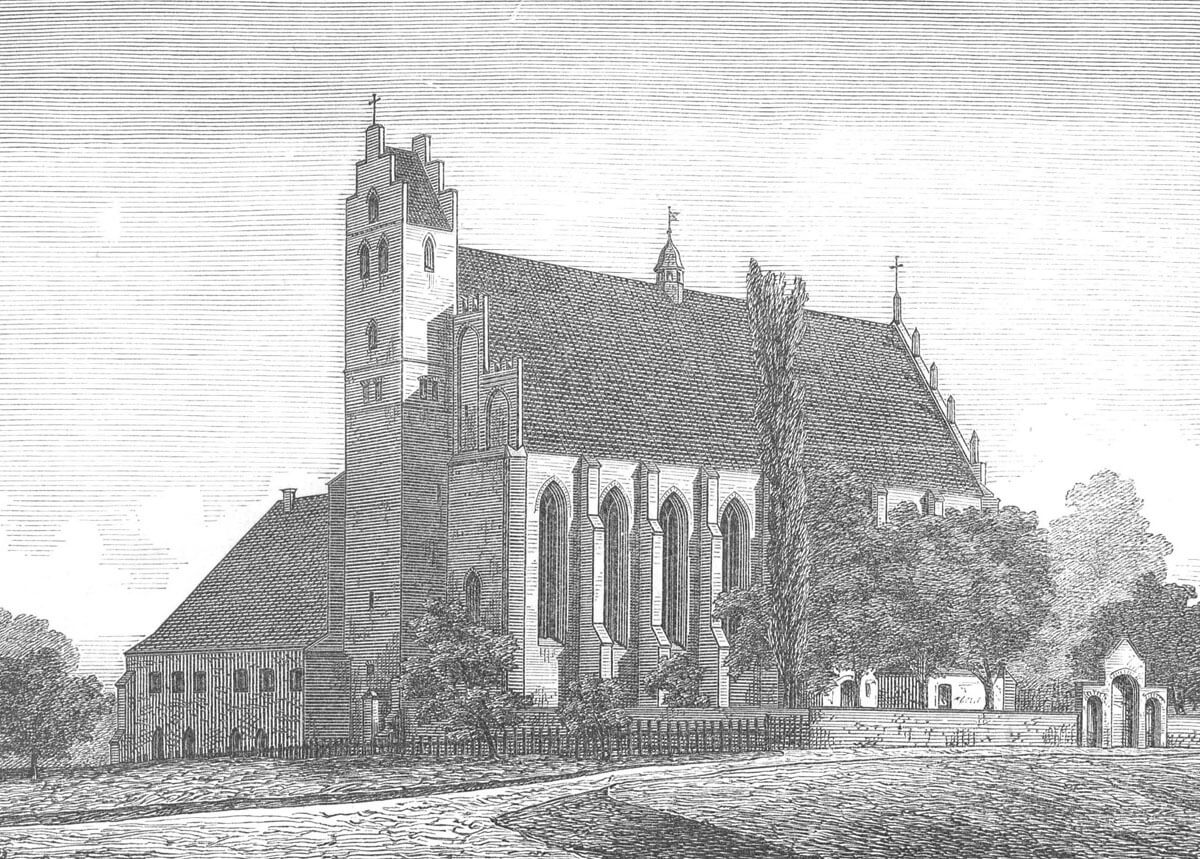

The construction of the church and monastery buildings lasted nearly half a century. It probably began in 1279, after the convent was approved by the prince. Works on the church were completed in the first half of the fourteenth century, but the date of its consecration is unknown. The first mention of a new temple appeared in 1342. The construction of enclosure buildings probably took a little longer and ended in the second half of the fourteenth century. A sacristy was added at that time, but in 1389 the entire church burned down and required a thorough renovation. During it, a low tower was erected next to it, buttresses widened, vaults were put up and wall paintings were made. In addition, at the beginning of the 15th century a porch was added, and in 1409 a building was erected for the Cistercian fathers taking care of the monastery, the so-called Opatówka. From the very beginning, the church was also a parish temple.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, after the capture of Gdańsk in 1308, the monastery found itself within the Teutonic Knights state. In 1342, the then Grand Master Ludolf von König approved all privileges and grants for cisterns, and the borders of the nuns’ property were also established. Large erratic boulders called “Standing” and “God’s Foot” were used to mark them, also marked oaks or trees, swamps, ditches and hills. In the following years of the fourteenth century, the monastery’s property expanded, among others, by the goods of wealthy noblewomen and townspeople joining the convent. Cisterns even had rents from Gdańsk tenements which were the wreaths of Żarnowiec nuns.

The period of prosperity ended in the 15th century. First, in 1433, the monastery was invaded by Hussite army and Polish troops supporting them. The nuns survived fleeing to Gdańsk, but seven years later the monastery was hit by a plague from which 11 sisters died. During the Polish-Teutonic Thirteen Years’ War the monastery was twice invaded and plundered by mercenary Teutonic Knights. In 1462 a battle was fought near Żarnowiec (also called the battle of Świecino) ended with a Polish victory over the Teutonic Knights. Fritz Raveneck, commander of the Teutonic army died during the battle, and his corpse was buried in the monastery church. After the end of the war in 1466, Żarnowiec was within the Royal Prussia belonging to the Polish kingdom, and at the request of the Oliwa abbot, Paul II, King Kazimierz Jagiellończyk confirmed all the privileges to the cistern nuns. In addition, in exchange for the losses they suffered, they received the Puck parish, which they had until 1558.

In the first half of the 16th century, Pomerania was embraced by the Reformation movement, resulting in the secularization of monastery life and the fall of discipline. Lay sisters fled to the city, and in their place had to hire secular people. A significant number of nuns also left the monastery, and the remaining 10 (in 1548) ceased to comply the order. In the years 1561-1566 the Żarnowiec grange was given as a pledge to Gdańsk residents, thus passing to the secular hands. Shortly afterwards, in 1589, the Cistercian monastery in Żarnowiec was deleted, and its buildings and properties were taken over by Benedictines from Chełmno. The last three cistercians left the monastery.

At the end of the 16th century, new nuns refurbished and modernized the monastery, introducing, among other, separate cells-bedrooms instead of a single dormitory room. In 1617, an abbess, the highest office in the hierarchy of female congregations, was elected in the monastery (previously the cistercians had only a prioress, subject to the Oliwa abbots). First abbess became Barbara Knutówna, patron of the famous Gdańsk painter Herman Han. The monastery’s independence improved its economic situation, but the increase in prosperity was stopped by the Polish-Swedish wars of 1626-1629 and 1655-1660. Also at the beginning of the 18th century, nuns were subject to contributions during the Great Northern War.

Around 1750, renovation works were carried out in the monastery church, and a school for girls was established next to the monastery. Benedictines were also a strong center of Polishness, their ethnic composition was, to say homogeneous, they came from Polish or long-polonized families. Therefore, after the partition of Poland in 1772, nuns were repressed by Prussian authorities. Finally, in 1834 the order was dissolved: the Prussian government forbade the admission of candidates to the novitiate, election of abbasses and took all property. The monastery buildings became the property of the parish, but due to the poor condition, a large part of the north wing was soon demolished. The first major renovation works were carried out at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, while the nuns returned to Żarnowiec in 1946 as repatriates from Vilnius.

Architecture

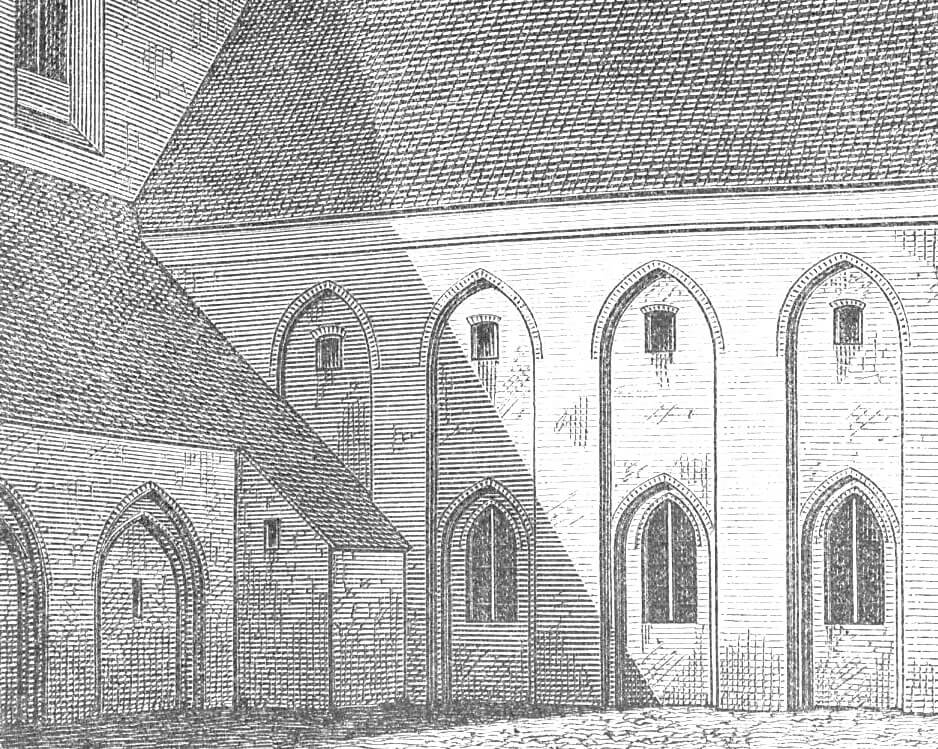

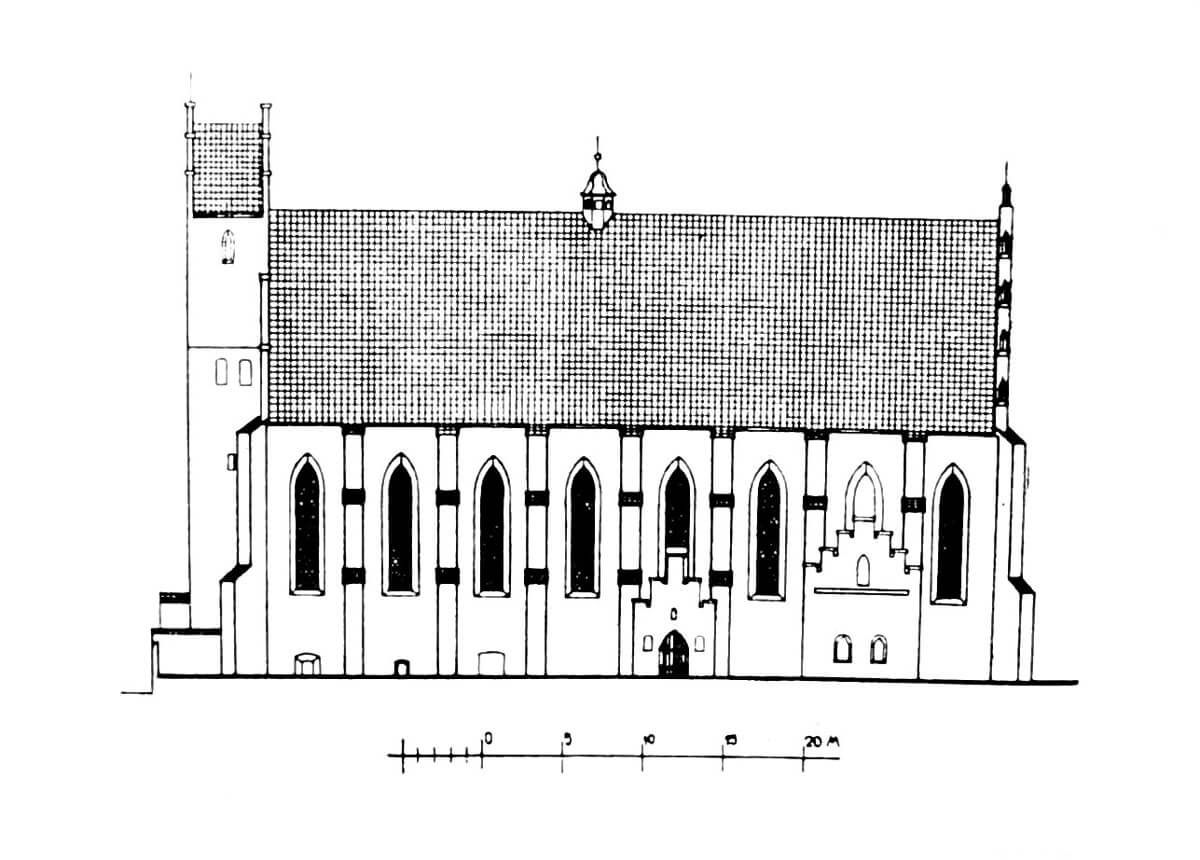

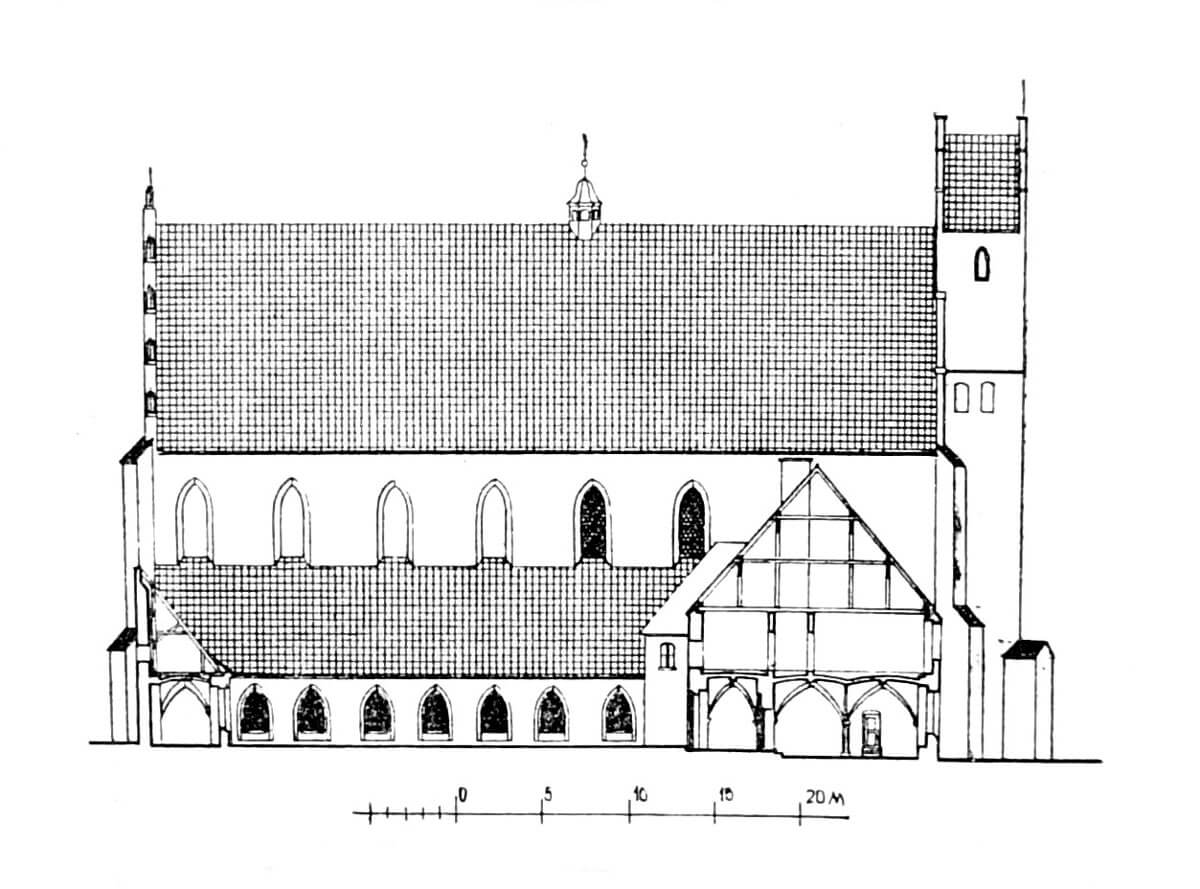

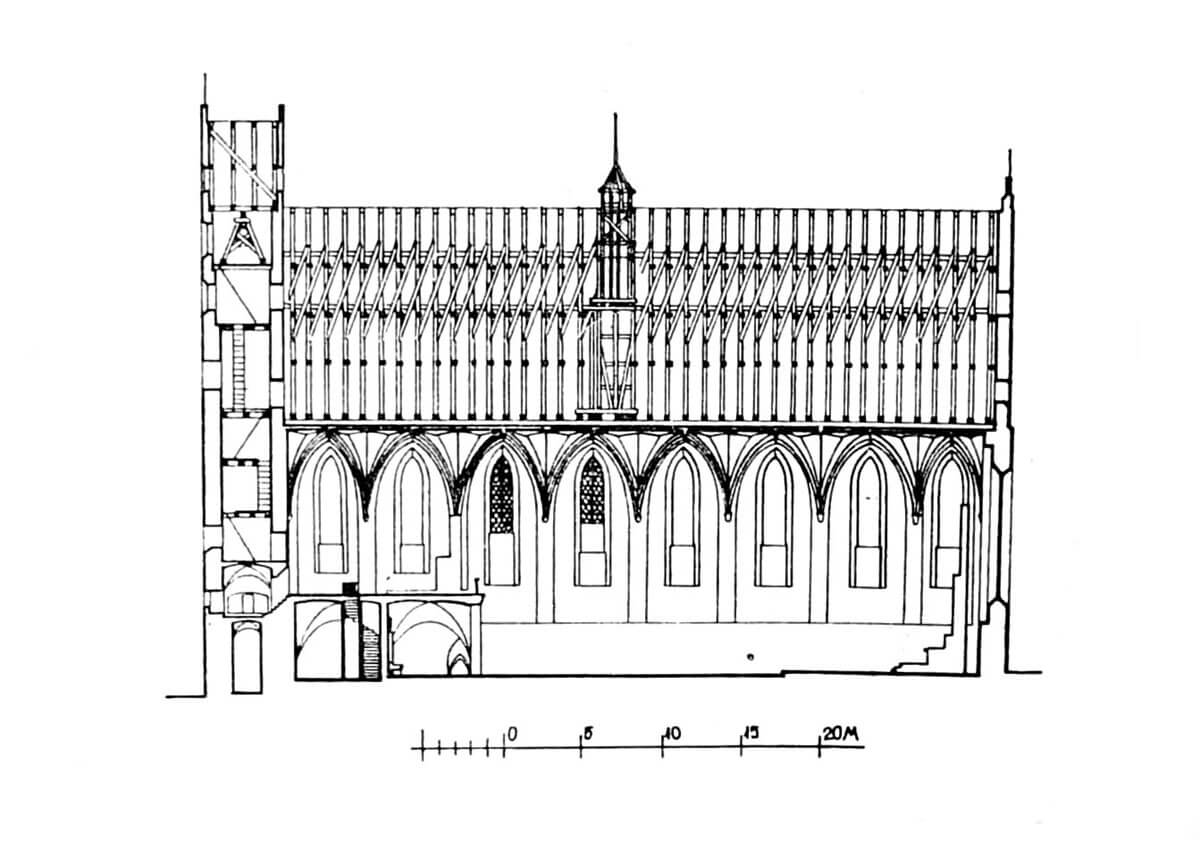

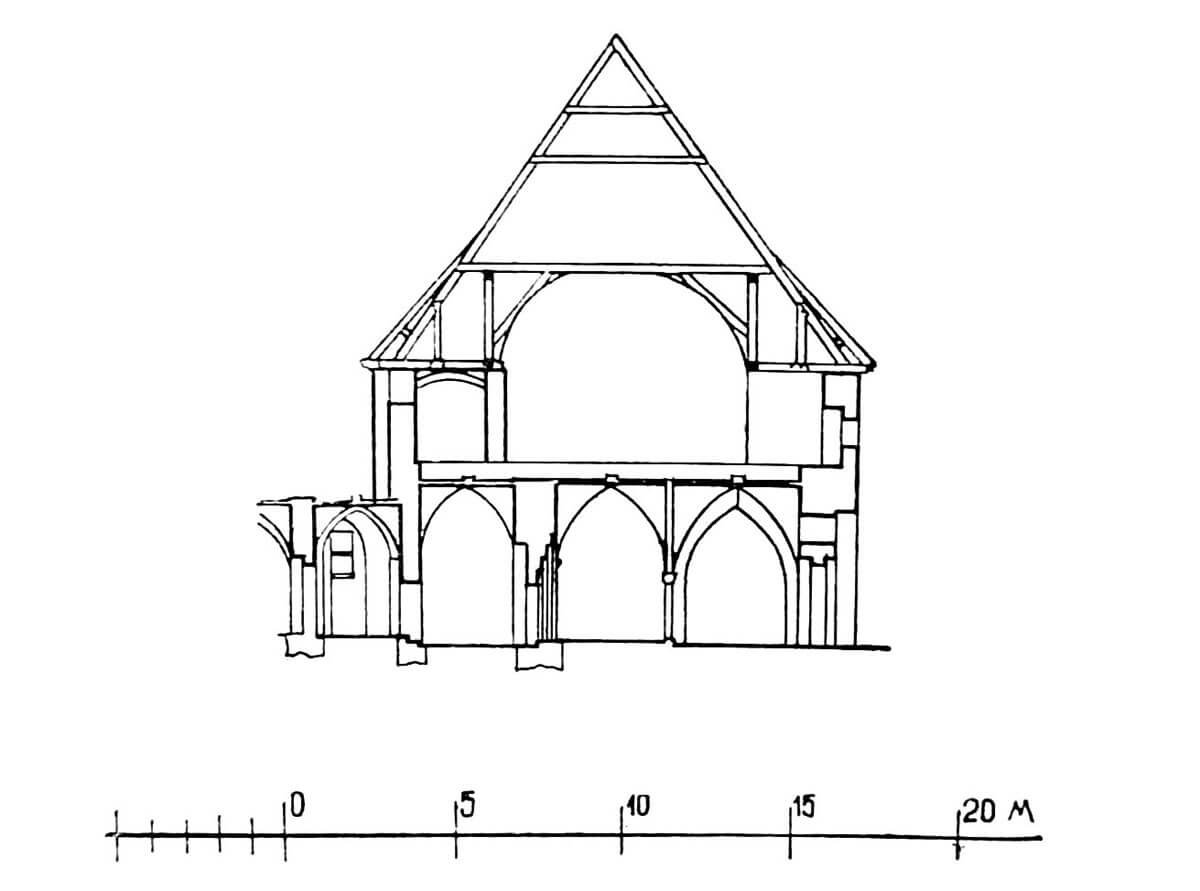

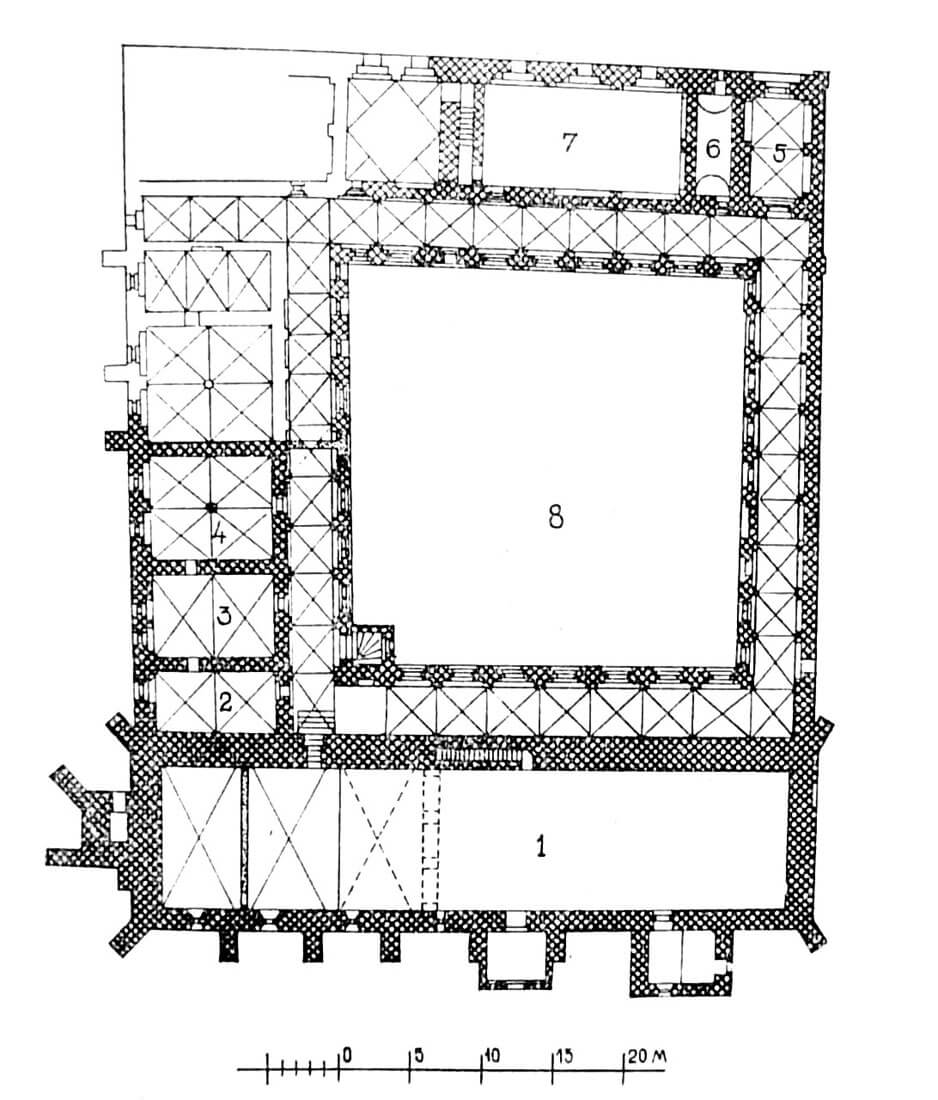

The church of the nunnery was built as a simple aisleless building on a rectangular plan, without an externally separated chancel. On the eastern side it ended with a straight wall, topped with fragmented by ogival recesses gable, and from the west a four-sided, slender tower was added in the second half of the 14th century. In the south, a Gothic porch and sacristy were attached to the church, both topped with straight stepped gables, similar to the larger gable located above the western wall. The church’s façades were surrounded with stepped, prominent buttresses, and the space between them was pierced by tall, pointed windows. From the north, where the monastery buildings adhered, the windows were shorter due to the mono-pitched roof of cloister. The main entrance to the nave was located on the southern side, there were three more northern portals: two from the cloister and one from the monastery to the choir.

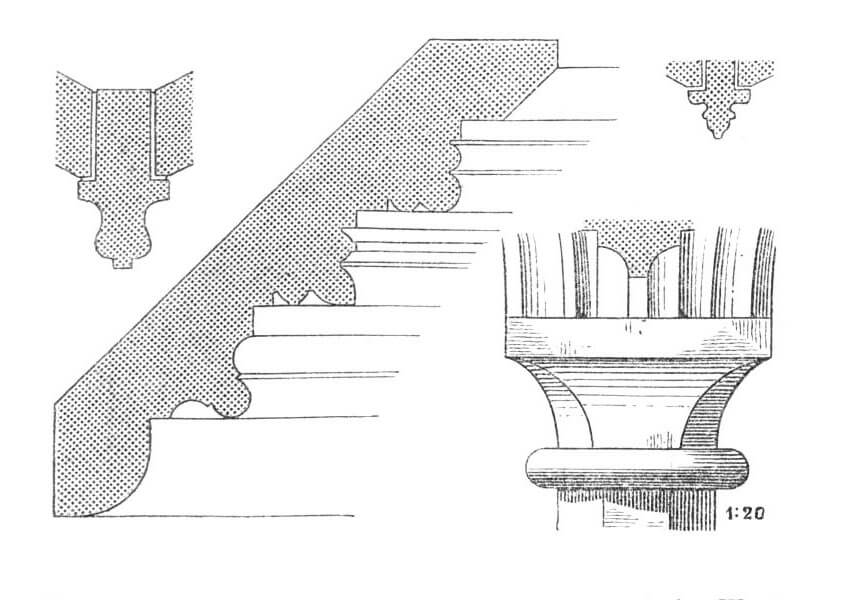

Inside, the eastern presbytery part was separated by raising a stone floor, covering the entire church. In the western part there was a choir of nuns, initially supported on offsets, located at the longitudinal walls of the nave. Its interior was accessible from the west wing of the enclosure and from the church through stairs placed in the thickness of the northern wall. A grate separated the nuns from the lay people. The nave and chancel were crowned with an eight-bay stellar vault from 1389. Each bay was represented by an external buttress on the south side, and a buttress on the north side were pulled into the interior. The ribs of the vault were fastened with bosses decorated with portraits of female and male heads, sometimes plants, as well as figures depicting farmers or angels. The sacristy was covered with a two-bay cross-rib vault, supported by bas-relief corbels made of artificial stone with the symbols of the evangelists, representations of figures, heads and architectural forms.

The monastery church was characterized by simplicity typical for the Cistercians, and at the same time high construction technique, sense of proportion, slenderness and almost complete lack of decorative details. The only exceptions were sculptures on vault supports and bosses. The distinguishing feature of the temple was also the west tower. Judging by the remains of the fireplace on the third floor, it was used as a guardhouse or signal point (even ships sailing on the sea can be seen from it).

Nunnery buildings grouped around the four-sided inner garth, were located on the north side of the church. They included two wings connected to the cloisters: north and west, as well as an additional side wing and a latrine tower with a porch. The cloisters were topped with rib vaults and illuminated with rows of pointed windows placed in deep recesses. In the southern part, above the cloister, there was an attic, accessible from the west wing. It probably served as a clothing store.

The most important part of the enclosure was a two-storey, (with basement) west wing. In the ground floor, it housed five cross-vaulted rooms with floors, due to the fall of the area, becoming lower in relation to the church. In order from the south, they housed: a two-bay scriptorium (now a treasury), a slightly larger but also a two-bay library, a four-bay chapter house, another four-bay room and a narrow three-bay hall. Interestingly, the first three rooms received a window arrangement incompatible with the arrangement of the vaults. Perhaps the western wall with windows was erected first, and then the vaults with a different interior arrangement than originally planned. The chapter house was crowned with a rib vault based on a single pillar made of limestone. Originally, probably along its walls were benches or seats for nuns sitting under the leadership of the abbess. The upper floor, accessible through the staircase on the south-west side, housed a dormitory, without a cell in the Middle Ages, and occupied by pallets placed against the walls. It was topped with a beam ceiling and illuminated by small windows embedded in deep recesses, by the eastern facade decorated with pointed arches from the outside (the western facade was smooth). Above there was an attic with a roof truss.

The north wing was two-story and had a basement. It was to it that the main entrance to the monastery led, set in a high ogival niche at the northern facade, leading to the cross vaulted hall. From the entrance hall, a richly moulded portal led to the eastern cloister and to further rooms of the wing. The hall was adjacent to the gatekeeper’s chamber covered with a barrel vault. In its wall there were small windows that once were used for conversations with clients coming to the monastery. Further west was a refectory with nine bays of the rib vault supported by two stone pillars. Its walls were divided by high ogival recesses, probably housing seats originally. In the thickness of the west wall there were stairs leading to the three basement rooms. Two of them were barrel vaulted, while the rib vault of the third one was supported on an octagonal pillar. The interior of the basement was originally illuminated by three windows set in the northern wall (currently they are below the terrain). A rectangular hole and a channel in the wall thickness to the refectory were pierced in the southern wall. Perhaps it was a kind of water supply, drainage or a kind of megaphone. The western part of the north wing was originally occupied by two more rooms, one of which could have been a fraternity. The not preserved upper floor could be connected through the porch with the latrine tower located in the north-west corner. It was illuminated by small windows located in the recesses, and the eastern facade was decorated with a stepped gable equipped with blendes. In the southern part of the floor there was a vaulted corridor, about the same width as the cloister in the ground floor. On the north side, there was a row of cells.

In addition to the enclosure complex, in 1409 on the north side a two-story house was built, called the Opatówka, housing the rooms of the chaplain and Oliwa abbots or bishops visiting the monastery. The building was located near the stream, by the wall surrounding the entire monastery complex with economic buildings. It was a small building on the plan of an elongated rectangle with rooms located on the sides of the central hall with a staircase.

Current state

The Cistercian monastery in Żarnowiec is one of the best preserved Gothic monasteries in Poland. To this day, the church (including the 15th-century tombstone of the mercenary commander Fritz Raveneck and the tombstone of Anna Gruduels from Puck from 1512) and the former cloister buildings adjoining from the north have survived. The western wing, shortened in the nineteenth century has survived, also the northern wing shortened and lowered by one storey, and the Gothic cloisters, mostly preserved and partly accessible to tourists. Further on: the chaplain’s house from 1404, rebuilt in 1635, the granary and the monastery wall from the 16th century are visible. The monastery treasury, inaccessible to tourists, contains literary monuments, including manuscripts from the 15th century, pastorals, richly decorated graduals, liturgical vestments and embroidery, sacred sculptures and old equipment.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler der Provinz Westpreußen, der Kreise Carthaus, Berent und Neustadt, red. J.Heise, Danzig 1884.

Domańska H., Żarnowiec, Warszawa 1977.