History

The first mention in documents about the church in Żagań appeared in 1272, in the document of Bishop Thomas II. The construction of this parish church, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, probably began soon after the town foundation, which took place between 1248 and 1260. In 1284, the prince of Głogów, Przemko, brought from Nowogród Bobrzański regular canons of St. Augustine, who received the parish church (the local parson Albert entered the order) along with the chapels belonging to it: St. Lawrence in the village of Stary Żagań, Holy Cross and the Holy Spirit at the hospital at the town gate. Then, in 1299, the canons obtained the Żagań castle from Przemko’s brother Konrad II. Thanks to the forethought of Abbot Tylman, Pope Boniface VIII took care of the abbey in 1295 and approved all its possessions, privileges and incomes.

At the beginning of the 14th century, the canons rebuilt and significantly enlarged the original church, on the north side of which they located their monastery buildings, erected on the site of the former castle. Work began on the most important part, the chancel, probably completed before 1342, when prince Henry IV was buried in the church, and then began to rebuild the nave and erect the tower. The latter had to be largely ready around 1348 and 1355, because then there were masses in the chapel on its ground floor, although in 1367 Abbot Martin asked the councilors to provide bricks and tiles and 20 carts of stone for the construction of the church and tower. Only abbot John II was to install a clock on it.

Under the abbot John I, in the years 1311-1314, a dormitory, a chapel and an abbey house were to be built. Around the mid-fourteenth century, according to documents, the friary was to have a school, scriptorium and one of the largest libraries in the region, owing its existence to the competent Abbot Trudwin, who was in office in the years 1325 – 1347. Trudwin sought to reform monastic life in the Żagań. He supported the studies of monks, among others he sent a brother Herman to study law in Bologna. In the friary, apart from the library, he even supported a few secular scholars who gave lectures and conducted classes at the school. Trudwin also turned out to be a good host, buying the villages of Bożnów, Grabik, Karczówka, Stara Kopernia and a mill on the Bóbr river for the abbey. During the times of abbot Nicholas I in the years 1365 – 1376, and John II Medic and Nicholas II, i.e. in the period 1376 – 1390, further intensive works were carried out on the expansion of the church and monastery buildings. The abbey flourished even more during the reign of the abbot Ludolf of Einbeck in the years 1394 – 1422. He emphasized discipline among the canons, became famous as a preacher at Wrocław synods and a supporter of the idea of conciliarism. He contributed to the development of the Żagań scriptorium and library, which, according to the account from 1473, had about 800 manuscripts.

A plague of misfortunes came to the Żagań community in the 15th century. First, the friary was affected by the Hussite Wars, then in 1439 the church tower collapsed (interestingly, the guard who served on it survived, pulled out from under a pile of rubble and wood), and further devastation was caused by fires in 1472 and 1473. All roofs were to be burned down, the vault of the chancel, library and in part of the nave collapsed. According to the chronicler, some of the equipment could have been saved, but such a panic broke out that the brothers escaping through the windows on the ladders left all their valuables in their place. After the destruction, the church and the claustrum buildings were rebuilt, covered with late Gothic vaults. This process lasted until around 1479, when the Bishop of Wrocław reconsecrated the church. Another consecration took place in 1482, but in 1486 fire again destroyed the friary, especially the church. This time the brothers fought for a long time to save the interiors from the fire, extinguishing the burning beams that fell inside, thanks to which, despite the destroyed roofs, the vaults and some equipment were saved (during the fire it was recorded that the library had water supply system). As a result, at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, thorough late-Gothic reconstruction of the church was carried out, significantly enlarging the nave. The completed building was consecrated in 1520 under the reign of Abbot Mechil III, although work was still being done on the monastery buildings. Under the abbot Paul Haugwicz (1489-1507), the two-person dormitory cells were to be divided into smaller ones, and the old bathhouse was adapted or rebuilt into a new abbey palace, while under his successors Jodok (1507-1514) and Christopher Nechel (1514-1522), changes were probably introduced in the layout and appearance of the claustrum rooms.

In the first half of the 16th century, the ideas of the Reformation began to be more and more popular in Żagań. The community was shrinking rapidly and no novices were admitted. Abbot Paul Lemberg, a supporter of changes, placed two Lutheran pastors at the church, which led to clashes with canons loyal to the old rules, and finally to the abbot’s resignation from office in 1525. In order to defend the monastic property, the Żagań canons asked for a special letter from King Ferdinand to protect their property. However, until the middle of the 16th century, they had to donate a sum of 630 guilders each year for the salary of evangelical preachers. After a sermon by one of them in 1539, paintings and altars were removed from the monastery church. The temple itself then passed from hand to hand and only in 1621 it become the property of the canons.

In 1634, Żagań was plundered by the Swedish army and the canons temporarily escaped. The dilapidated but still functioning friary was additionally damaged by the fires of 1677 and 1730. The rebuilt interiors of the church and friary have already received a Baroque form, the shape of the windows and the shape of the roofs over the nave and tower of the church were changed, and the claustrum was thoroughly rebuilt. In 1810, by order of the Prussian government, the community was dissolved. The last abbot was forced to resign from the office, becoming in return the pastor of the Catholic parish. During the dissolution, the library was robbed of valuable manuscripts, incunabulas and old prints, partially taken to Wrocław, while the monastery buildings housed a school, a vicarage, a district court and a prison. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the monument was repeatedly repaired and renovated, mainly in the years 1848 – 1853, 1946 and 1983 – 1988.

Architecture

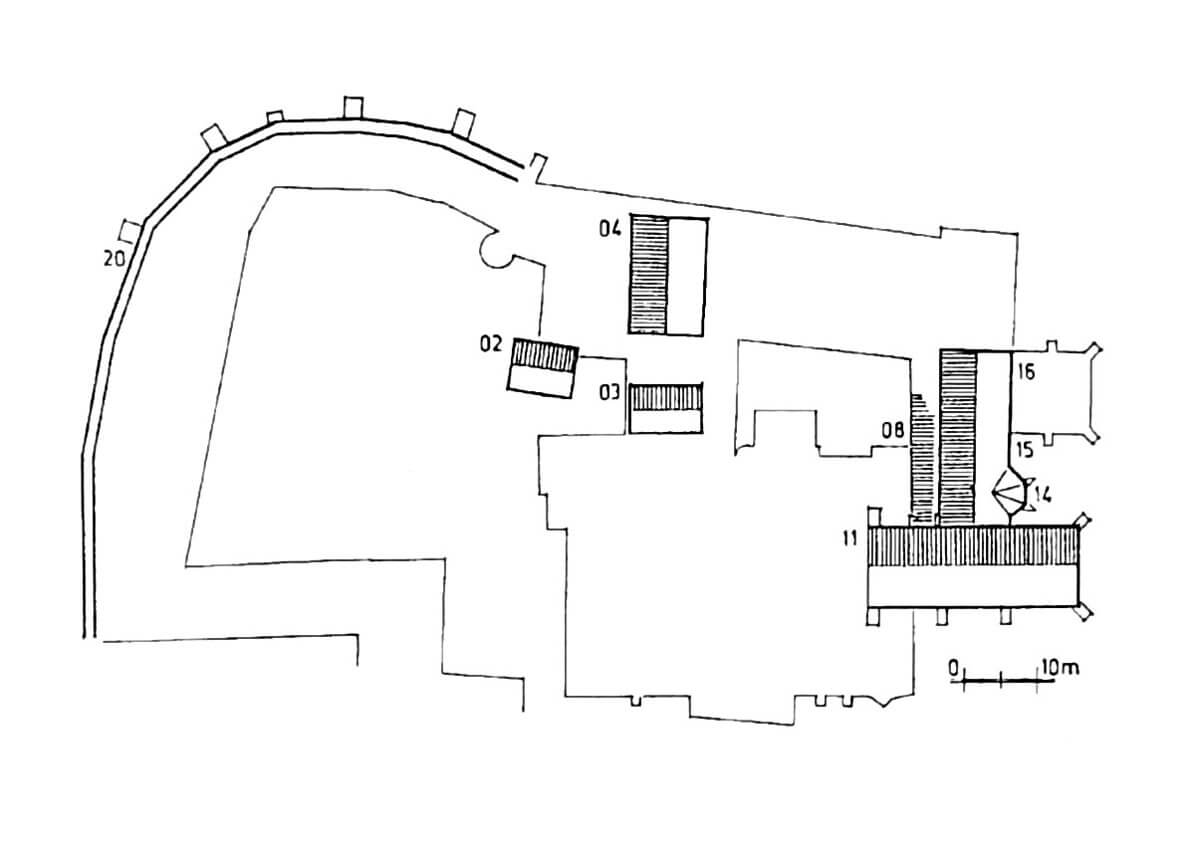

The church and monastery buildings were situated in the north-west part of the town. From the north and west, they were in close proximity to the defensive walls, while on the other sides they were adjacent to the streets and plots of bourgeois buildings. Żagań itself was established on the northern edge of a large forest complex, on the eastern bank of the Bóbr River, at the intersection of trade routes. The friary consisted of a church, claustrum buildings on its northern side, built on the site of the prince’s castle, where with time surrounded the cloisters garth, and auxiliary and enconomic buildings on the western side of the church.

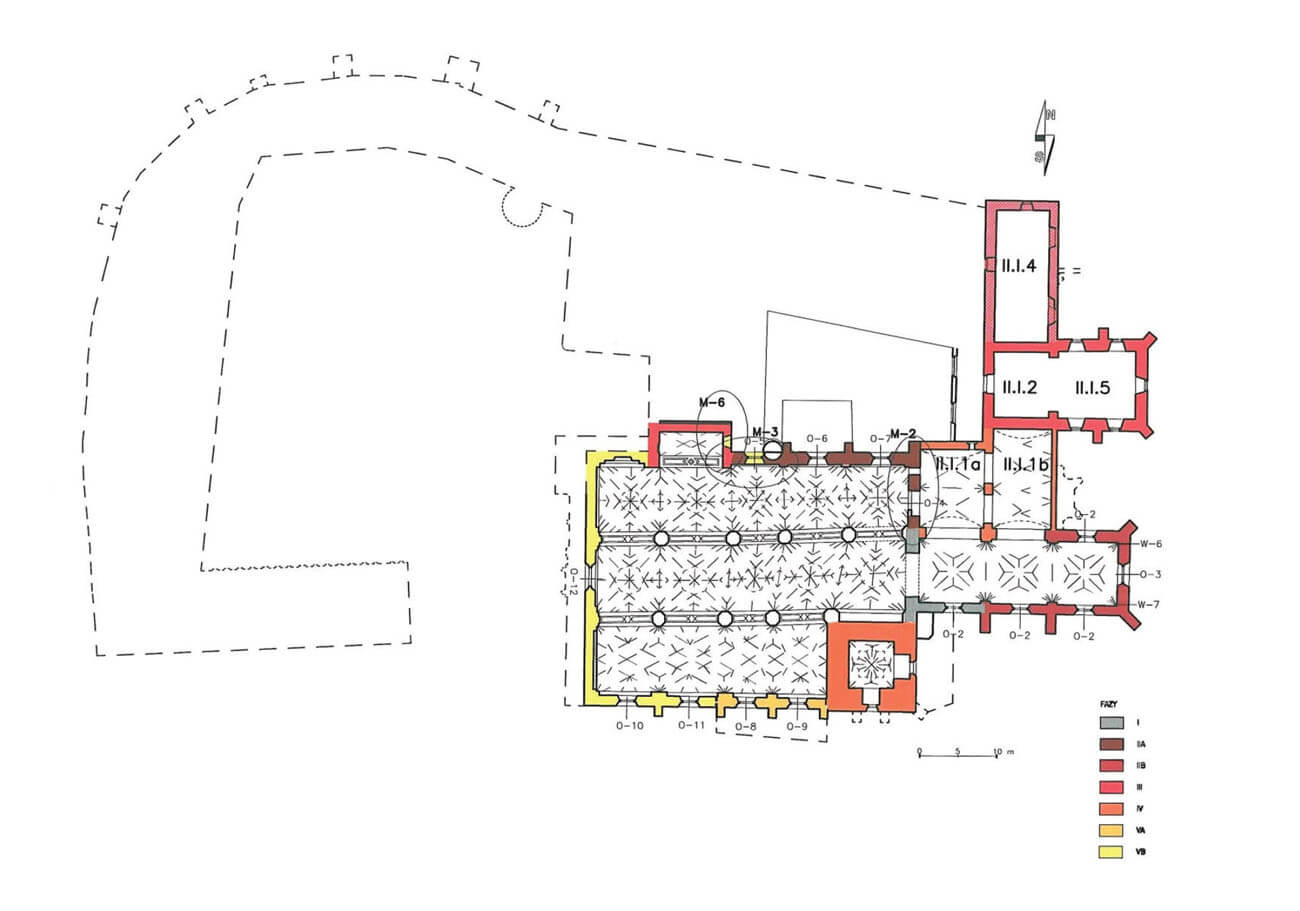

The original church from the 13th century was probably a stone aisleless structure with a narrower and probably lower chancel on the eastern side, two or three bays long. The late-Romanesque building was smaller than the later Gothic one, probably occupying the eastern part of the later nave and the western part of the Gothic chancel.

The rebuilding from the first half of the 14th century resulted in a thorough reconstruction of the chancel of the late Romanesque church into longer, Gothic one, also made of erratic stones, originally not plastered. From the west, a nave was added to the chancel, probably initially two-aisle, in hall form, three-bay, thanks to which the entire structure was not symmetrical in plan. The nave was clasped with buttresses, similar to those used in the chancel, but made of bricks. Between them, three early Gothic pointed windows were pierced from the north, and probably four more windows illuminated the southern aisle, including one from the east and three from the south. The facades were decorated with a stepped cornice and a frieze. Together with the nave, a massive, four-sided tower was erected on its southern side. It was made of stone, but with an external brick face. Its ground floor was originally lit by three windows: narrow, high and pointed. Despite the thick walls, the tower was supported from the south with buttresses, two at an angle and two perpendicular to the axis of the church.

In the second half of the fourteenth century, the monastery church was enlarged. The chancel was extended by one, straight ended bay to the east, so that the whole was divided into three square-like bays covered with a stellar vault. The interior was illuminated by seven high windows on both sides, set between stepped buttresses. They were pointed and filled with traceries. For the reconstruction of the chancel, erratic stones were used and bricks to create architectural details.

At the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, the spaces between the buttresses of the nave of the church were gradually filled with chapels. The oldest was built in the eastern part of the northern aisle. It was covered with a cross vault with pear-shaped ribs based on conical corbels. Another chapel on the west side was crowned with a stellar vault. In addition, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, on the south side of the chancel and the eastern side of the tower, an elongated annex was created, housing the tomb of Prince Henry IV the Right. It shortened one of the tower’s windows, just like the earlier chapels obscured one of the nave’s windows. After 1439, the church tower was rebuilt, the storeys of which were separated by plastered friezes, and the facades were decorated with pointed blendes. In its upper storey, one large, two-light window with richly moulded jambs was pierced on each side, while the top storey was illuminated with small openings closed with segmental arches.

The destruction of the church from the second half of the 15th century resulted in the reconstruction of the nave from a two-aisle into a much larger three-aisle in the form of a pseudo-basilica. First, two eastern bays of the southern aisle were erected, adjacent to the east with the tower. After a short break, two more bays and a façade were added from the west, eventually creating a five-bay nave with very wide aisles. The central aisle was created slightly higher than the side ones, but it was not illuminated by its own windows. Its bays obtained very asymmetrical forms, caused by the need to adapt to the two older pillars and the width of the tower. Together with the northern aisle, it was covered with stellar vaults, while the southern aisle was topped with a net vault. The whole was covered with a gable roof based on the eastern gable and a magnificent 20-axis western gable, divided into five levels with plastered friezes. Between them there were as many as 59 blendes crowned with segmental arches. The lighting of the nave was provided by large, pointed and splayed windows. The main entrance was located in the central aisle from the west, but the auxiliary also functioned from the south, in the first bay from the west. The church was also connected with the claustrum: through the chancel to the chapel and through the northern aisle by the west wing and the cloister. In the south, the passages led to two late Gothic, narrow chapels inserted between the buttresses.

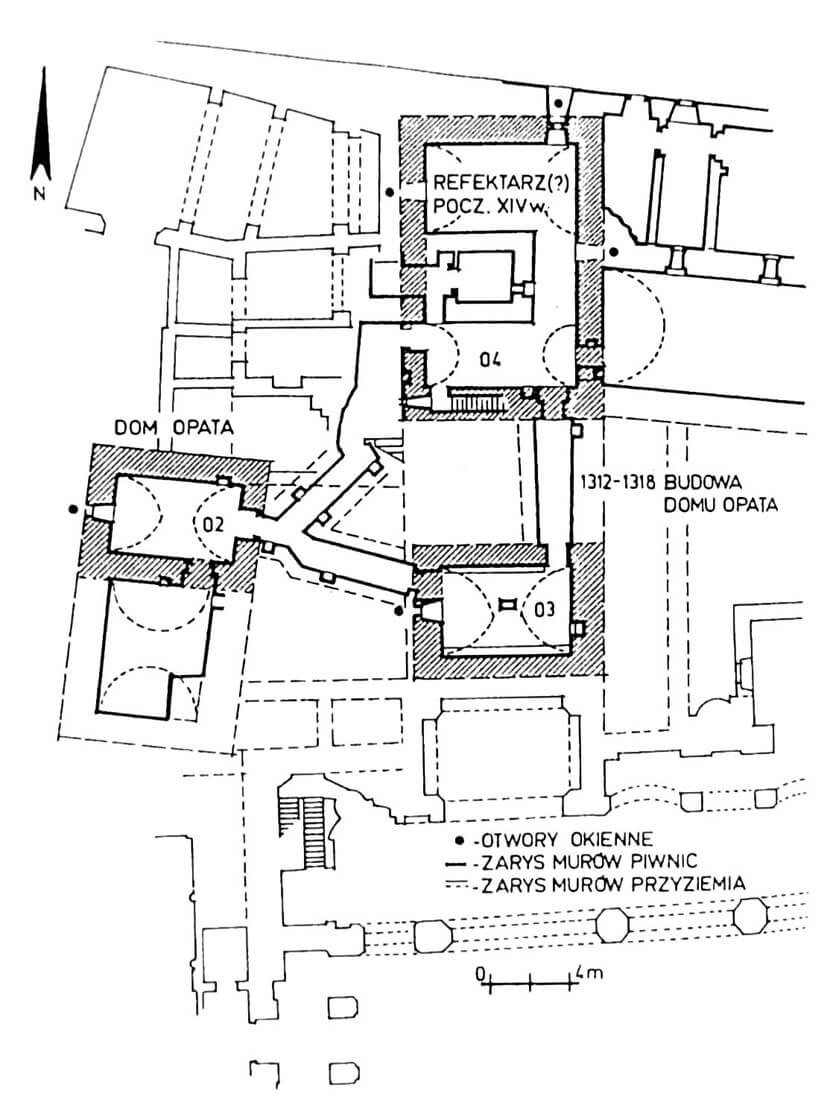

The oldest monastery buildings formed the eastern range, probably erected with the use of the relics of the ducal castle buildings. This earliest structure was built of stone on a quadrilateral plan, 12 x 12.3 meters, with walls 1.6 meters thick, reinforced with corner buttresses and presumably divided into three floors. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the eastern range was formed by two rooms in the ground floor, one of which could have been used as the chapter house, and the next, closer to the chancel of the church, as the sacristy. The latter had two bays covered with a cross-rib vault based on consoles, lit by one window from the east. The entrance to it led through a portal from the north, from the presumptive chapter house, which was single-bay, covered with a cross vault. Then, from the north, a third room was added, and soon after the chapel was placed in the room between the eastern wing and the chancel of the church. It played a sacral role primarily during the works on the extension of the chancel. It had a three-side ended closure from the east with a single window and a cover with a cross-rib vault based on geometric corbels. A staircase was pressed between the chapel and the chancel, which provided vertical communication to the east wing. Partially embedded in the chancel wall, it led to the dormitory on the first floor, initially probably of a timber structure. The buildings were complemented by a prison cell, located in the southern wall, under the stairs, from where the inmates could participate in the masses. Acoustic contact with them was provided by a small opening in the wall between the cell and the chancel.

Along with the eastern wing of the claustrum, the construction of the eastern wing of the cloisters began, and then the remaining ones that surrounded the inner garth. They were covered with a cross-rib vault with stone, moulded ribs and arches separating similar to squares bays. Towards the inner garth, the cloisters opened with pointed arcades, which initially were unglazed openings, equipped with glass only at the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

In the second half of the fourteenth century, the eastern wing was extended from the north by an additional room that served as a fraternity, i.e. the room in which the canons worked. The square-shaped room had two levels. The lower one was probably used as a pantry, while the upper one, the proper fraternity, probably housed the scriptorium. The first floor was divided into three bays, covered with a cross-rib vault. The ground floor was topped with a brick barrel and illuminated by five windows. In addition, latrines were built, located on the northern side of the wing above the town moat, connected with the dormitory by a two-story porch.

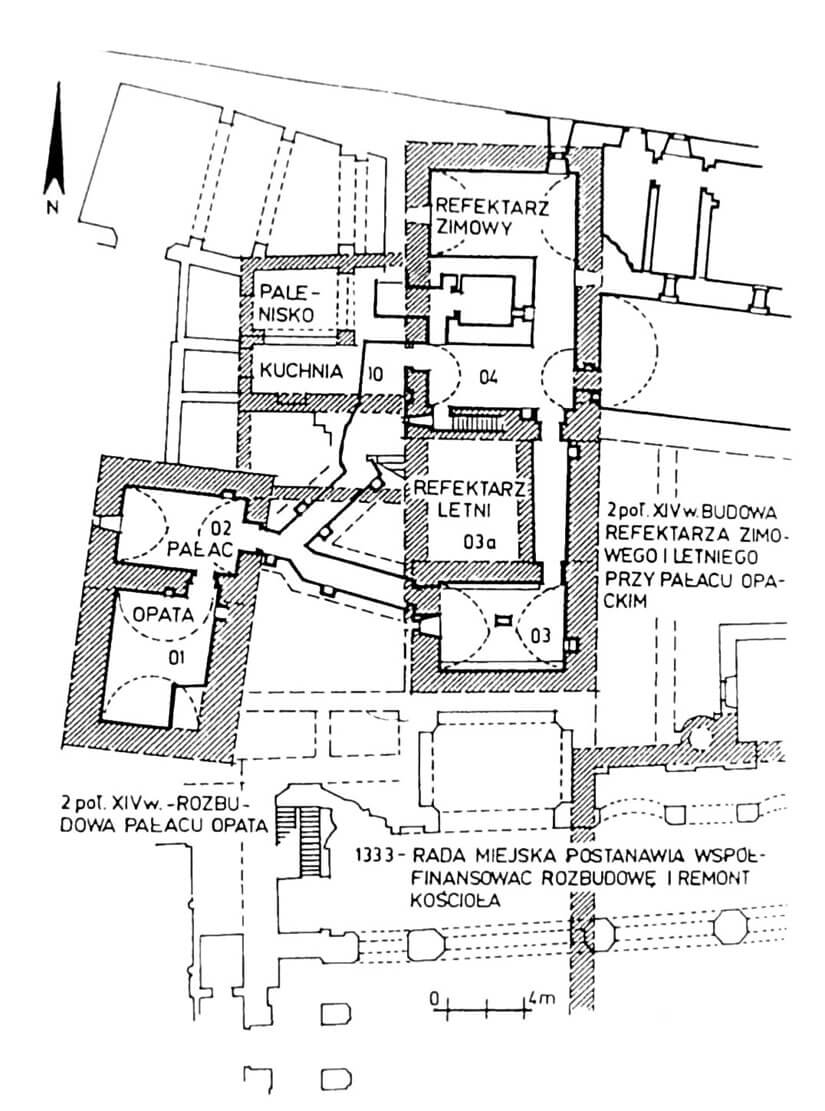

On the west side of the claustrum there was a small, vaulted, stone abbot’s house measuring 4 x 6 meters, and a nearby building with an uncertain function, perhaps a kitchen. The abbot’s house was enlarged by a northern room in the second half of the 14th century, but it was still a modest building, probably resembling a tower house. The entrance to its ground floor led from the east, while the first floor was most likely accessed by external timber stairs. The ground floor was lit only by slit windows, larger, Gothic openings could only be located on the first floor.

The west wing of the friary from the second half of the fourteenth century was located on a slightly lower ground, which sloped north-west, creating a difference of up to 3 meters. In the building with dimensions of 7.8 x 12.4 meters, there was a winter refectory and a kitchen. Initially a single-storey wing, in the second half of the 14th century, it was transformed into a two-storey building, with a pantry and a heating furnace at the bottom, and a refectory moved upstairs. There was also a small summer refectory nearby. From the end of the 14th century, all of the above rooms (both refectories, abbot’s house) were connected by a system of passages covered with brick vaults. The buildings of the Gothic friary were complemented by a great granary attached with its shorter side to the defensive wall in the western part of the complex. It was a brick building with five floors, a basement, with facades decorated with blendes.

At the end of the fourteenth century, the northern wing was built, which finally closed the buildings around the garth. It was a stone house elongated on the east-west line, inside divided into two rooms. Its lighting was provided by windows pierced only from the north side. Along with the placement of the partition wall, brick barrel vaults were installed in the rooms, above which there were probably rooms on the first floor, set on the same level as the adjacent fraternity and refectory. Presumably, there was a cellarium in the ground floor, while on the first floor there was a kind of an hall or a dormitory.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the chapter house in the eastern range was enlarged by a four-sided, buttressed eastern part. This brick extension was divided into two bays, illuminated by six windows, covered, like the older part, with a cross-rib vault. Both parts were connected by a wide arcade pierced by the former eastern wall, and transformed into the chapel of St. Anna. At the same time, the growing collection of books on the first floor forced the building of a new library, occupying the space corresponding to the chapel on the ground floor. The library was probably vaulted, a new scriptorium was created next to it, and the dormitory was transfered into a room above the fraternity.

In the late Middle Ages, the area of the west wing of the claustrum was leveled, which turned its ground-floor rooms into basements. After carrying out these works, a new chapter house was erected in the southern part of the wing, at the corner of the nave of the church. Its rectangular interior was covered with a stellar vault. Above, there could be one or two floors, as evidenced by numerous Gothic windows with moulded jambs and decorative tracery. The chapter house itself was probably connected with the church and with a two-aisle summer refectory, and the latter was accessible from the cloister from the east and from the passage on the north side. The passage separated the winter refectory from the smaller summer refectory.

The destructions from the 70s of the 15th century forced changes on the upper floor of the southern part of the east wing. At that time, a kind of gallery was created there, open to the chancel with wide, pointed arcades separated by a single pillar. Two quadrilateral rooms of the gallery were vaulted, and the western one was opened to the aisle of the church with two windows (one of them was originally the eastern window of the nave). In addition, the location of the dormitory was changed once again. The living quarters of the canons were then located in a newly erected building, attached from the south to the town defensive wall in the north-west part of the complex.

Current state

The friary and the church, unlike the town, avoided major damages during the Second World War, but their medieval layout and form underwent a thorough reconstruction in the 18th century, with further changes introduced in the 19th century. Most of the Gothic features have been retained by the former monastery church, distinguished by a great tower and gables of the nave. Unfortunately, the façade was obscured by a loggia from the beginning of the 17th century, and the church’s windows were transformed. Late Gothic vaults have been preserved in the nave and chancel, although the interior design has been made Baroque. Among the monastic buildings, only a few have a medieval form today, e.g. the chapel of St. Anna in the east wing. Some of the original ground-floor rooms have been preserved on the level of the present basements, others were demolished in the 18th century (abbot’s palace, summer refectory, 15th-century chapter house). In the western part of the complex, there is a body of a Gothic granary from the second half of the 14th century and a fragment of the town defensive wall surrounding the friary from the north-west.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Dorozd-Turek M., The former abbey of Canons Regular of St. Augustine in the context of the city of Żagań, “Architectus”, 2(32), 2012.

Klasztor augustianów w Żaganiu, red. S.Kowalski, Zielona Góra 1999.

Kowalski S., Zabytki architektury województwa lubuskiego, Zielona Góra 2010.

Mandziuk J., Dzieje kanoników regularnych św. Augustyna na Śląsku, “Saeculum Christianum”, 14/2007.

Pilch J., Kowalski S., Leksykon zabytków Pomorza Zachodniego i ziemi lubuskiej, Warszawa 2012.