History

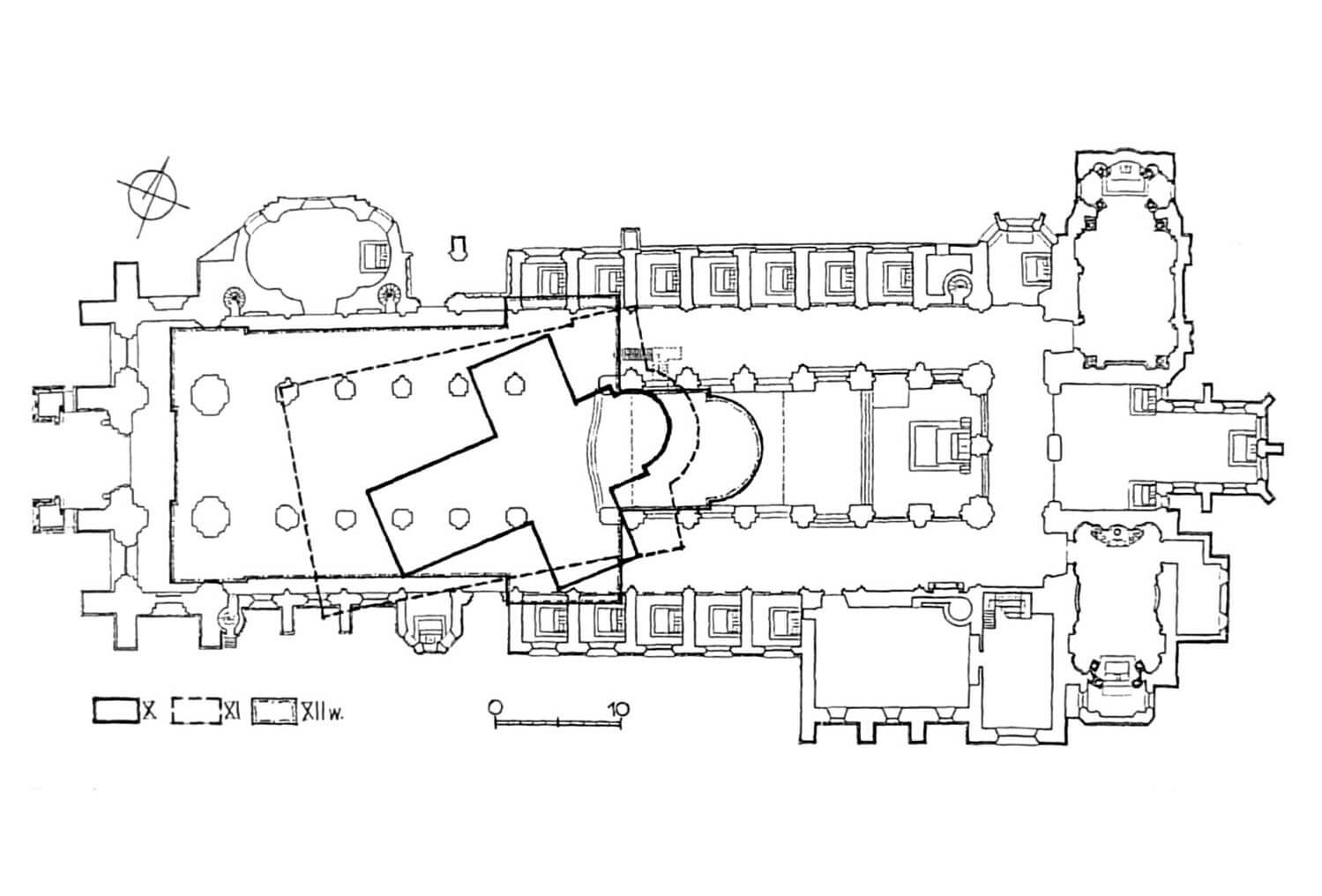

The first church on the site of today’s cathedral was built in the Wrocław, most probably in the first quarter of the 10th century, perhaps still in the Slavic rite. This church was enlarged in the 60’s or 70’s of the 10th century during the Czech influence, after the conquest of Silesia by Boleslaus II, Duke of Bohemia. It probably served as the court chapel of the tribal prince, and its resemblance to the pre-Romanesque church in Libice in Bohemia suggests that the construction was supported by Slavník, the prince of Libice, who supervised Silesia on behalf of the Czech ruler. The importance of the church grew after the conquest of Wrocław by Mieszko around 990. After 1000, due to the establishment of a bishopric in Wrocław, the first church began to serve as a cathedral. It was destroyed during the pagan reaction and the invasion of the Czech prince Bretislav I in 1037-1038. For the next several years it was in the form of a progressive ruin, while the Bishop of Wrocław was in exile in Smogorzów and then in Ryczyna.

In 1040, Casimir the Restorer recaptured Silesia from the hands of the Czechs and their pagan allies, and in 1051 renewed the Wrocław bishopric. Around the third quarter of the 11th century, on his initiative, a new, early Romanesque cathedral was built on the ruins of the old church, adding splendor to the Wrocław stronghold. Its first bishop was Jerome from Rome, who brought with him relics to attract pilgrims and support the construction process.

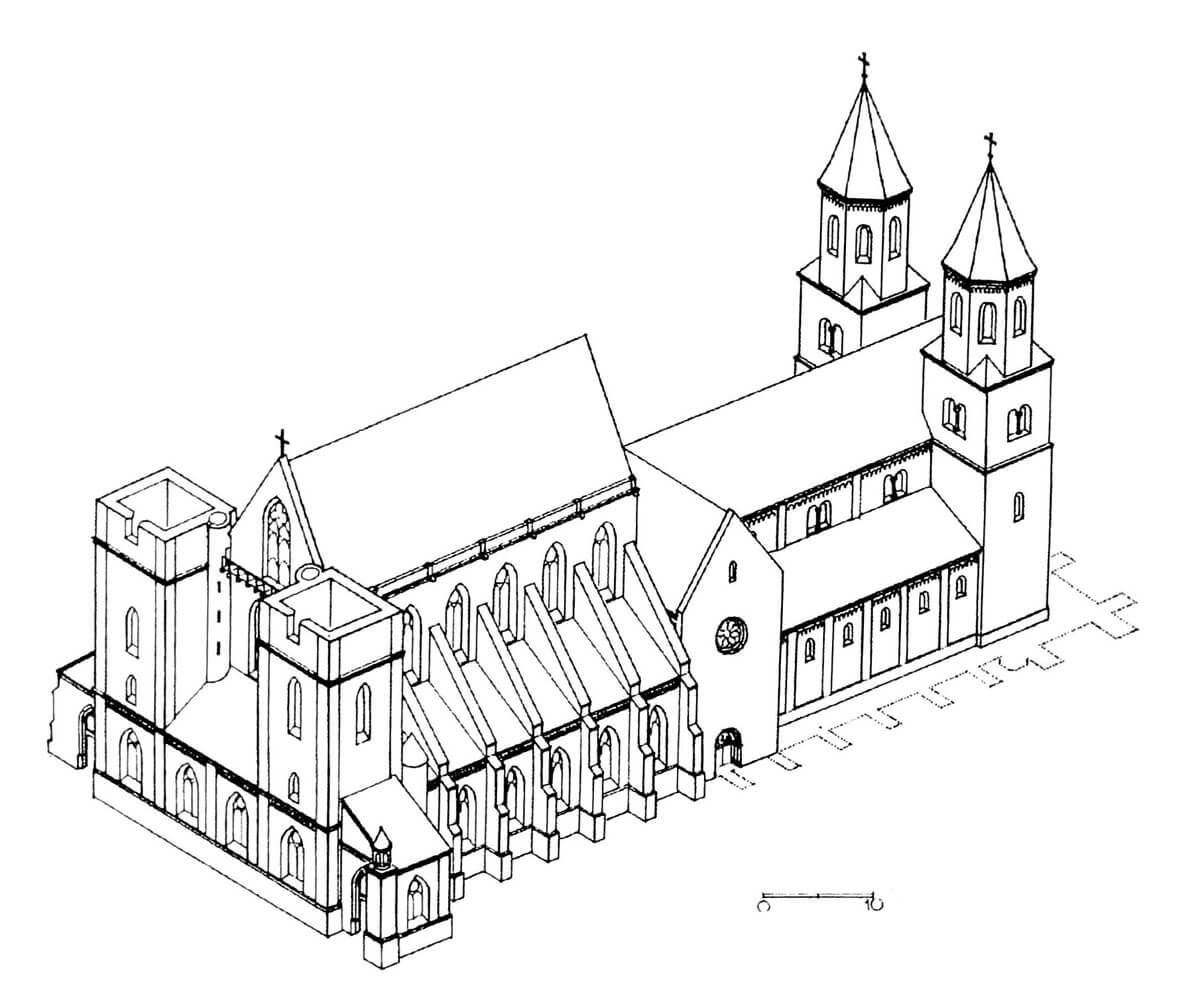

In 1158, Bishop Walter of Malonne, using a large part of the walls of the previous church, started building a more magnificent Romanesque cathedral for the Wrocław bishopric. The reason for the reconstruction could have been the abatement of the church and cracking of the walls, but also ambitious activities and the desire to erect a more innovative building. The two-tower, three-aisle basilica with a transept was built mostly during the reign of prince senior Bolesław IV the Curly, and was completed during Bolesław the High in 1180, when it was consecrated by bishop Żyrosław II. During this period, the supremacy of the senior prince over Silesia, which was transformed into several hereditary district principalities, ended.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the process of changes in the Polish Church, as well as the changing political and economic relations in Silesia, prompted the bishops to pursue a policy aimed at strengthening the position of the Church in relation to the rulers. This resulted, among other things, in the construction of new or rebuilding of old churches into more magnificent ones, using new, already Gothic architectural forms. In Wrocław, the Gothic reconstruction was carried out in several stages. In 1244, despite the devastation of the Silesia by the recent Mongol invasion, but also with the development of Wrocław after its foundation (charter rights) in 1242, the construction of an early Gothic chancel with a rectangular ambulatory began (preserved to this day in an unchanged form, it is one of the oldest Gothic buildings in Poland). Work on it was started by Bishop Thomas I during the reign of Bolesław II the Horned, and completed in 1272 by Thomas II during the reign of Prince Henry IV Probus.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the construction of a new Gothic nave began, lasting until the second half of this century. The first works could have been undertaken after the chancel of the nearby collegiate church of Holy Cross was completed in 1295, which, with its Gothic soaringness, had to contrast with the still Romanesque body of the cathedral. Therefore, the reconstruction began either in the times of bishop John Romka, who died in 1301, or under Henry of Wierzbno, who held the office of bishop from 1302. In 1306, an indulgence was issued, the income from which may have been used for the first stage of work – the erection of foundations, two floors of towers and external walls of the aisles. After the death of Henry in 1319, there was a seven-year break due to a vacancy on the bishop’s seat, and then the previous construction workshop probably passed away. The resumption of works took place after the election of Bishop Nanker in 1326, with a significant change in the architectural concept of building of the nave. Finishing works had to be carried out by Bishop Przecław from Pogorzela since 1342, for whom also in the years 1354-1361 master Pieszko added the St Mary’s Chapel to the choir, and in the north a porch with the Imperial Choir.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the construction of towers was continued, and chapels and porches were built between the buttresses. In 1408, the annex at the north-eastern tower was transformed into the chapel of St. John the Baptist, and in 1455 an annex on the opposite side was transformed to the canonical sacristy and arcades were built under the so-called a holy spring with a Romanesque figure of St. John. An important stage must have been the setting of the knob on the finished helmet of the north-west tower in 1416, which coincided with the reign of Bishop Wacław from the Silesian Piast dynasty.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the entire area of Ostrów Island was fully owned by the cathedral clergy and the collegiate church of Holy Cross, and the monarchs and their representatives were on the left bank of the Oder. Shortly thereafter, a series of natural disasters in the form of fires and storms caused significant damages to the cathedral, followed by forced costly repairs and reconstructions. At the same time, the progressive Reformation covered more and more people and decreased the income of the Church. Bishops, starting with John Thurzon, usually resided in their seat in Nysa, while Wrocław was ruled by the chapter, which was much more economical in managing the funds. Thus, most of the works were then modest and utilitarian, without high value, except for the sacristy portal from 1517, which was one of the earliest manifestations of the Renaissance in Silesia. After the fire of 1540, the vaults of the nave and the roof were unfortunately rebuilt, and after 1556 new Renaissance helmets were installed on the towers. Then, in the years 1590-1605, the interior of the lower part of the choir was rebuilt along with the Gothic rood screen.

In 1633, during the battles of the imperial army with the Swedes and the Saxon-Brandenburg army, the south tower, the southern part of the cathedral and the sacristy roof burnt. The destruction was rebuilt, and in the following years of the 17th and 18th centuries, several baroque chapels were added to the cathedral. In 1759 a great fire broke out in the bishop’s court and in a nearby inn, which was then transferred to the cathedral. It mainly destroyed the western towers and the western gable. For the next almost 20 years, reconstruction was carried out, continued with inept renovation works from the first half of the 19th century, and renovation works carried out in the spirit of Gothic purism in the second half of that century, the effect of which was destroyed anyway in 1945, when the cathedral was destroyed during pointless fighting. After the war, it was rebuilt again in the years 1946-1951, and long-term restoration works were carried out in the following years. In the years 1988-1991 the towers of the western facade received slender helmets.

Architecture

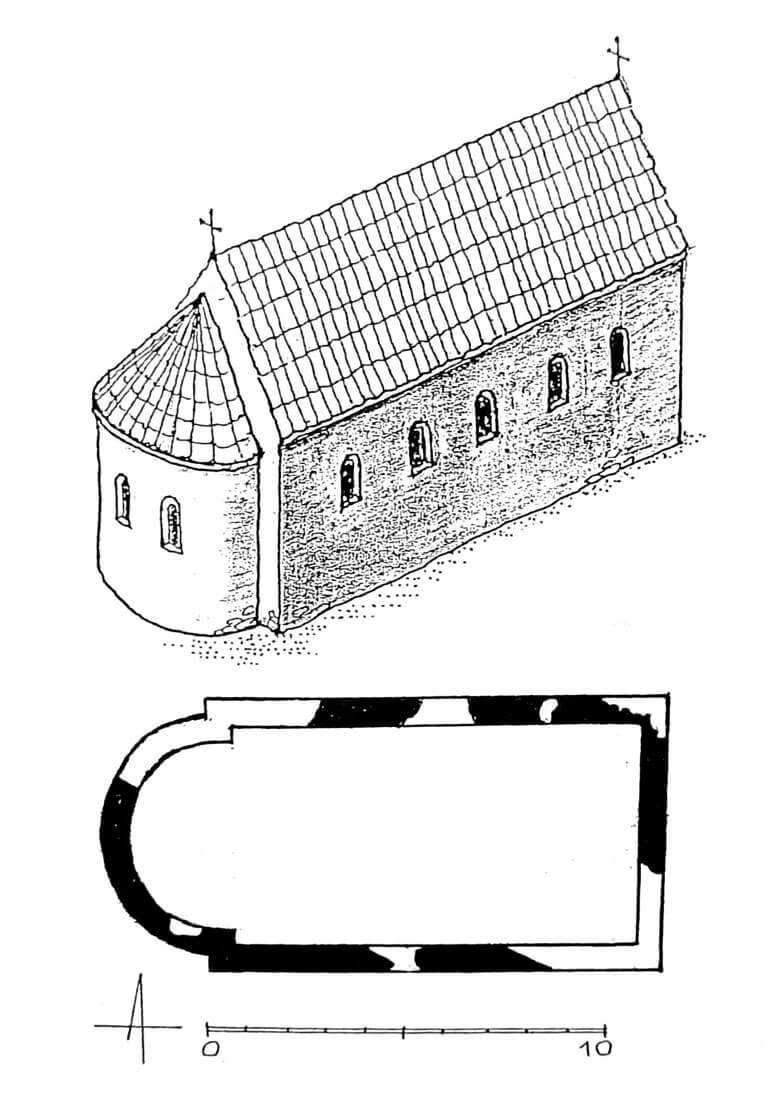

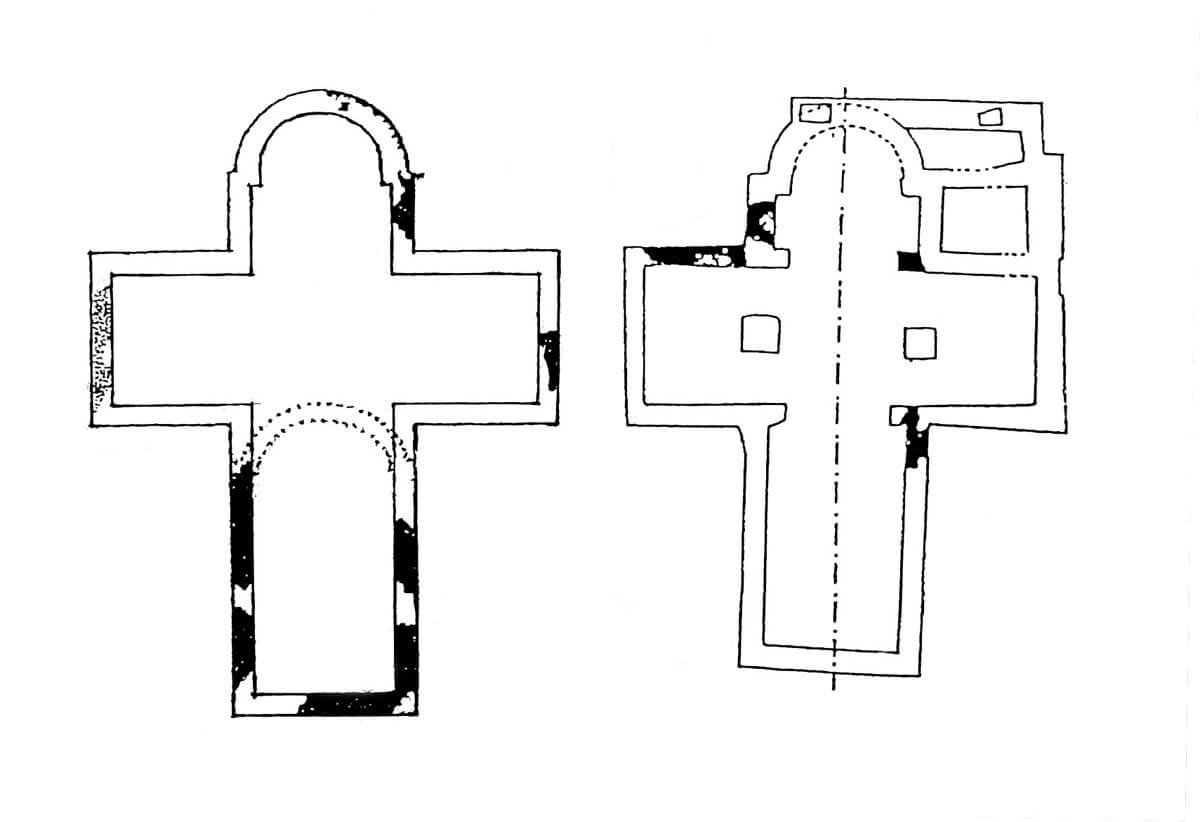

The oldest church and then the cathedral were erected on one of the river islands of the Oder, which split into several currents near Wrocław. At the end of the 10th century, this island obtained massive wood and earth fortifications, which also included the eastern end of the island, where sacral buildings were located. The first church was probably a simple building consisting of an aisleless, rectangular nave, about 11.5 meters long, about 6.5 meters wide, closed in the east with a slightly narrower apse. It was made in the opus incertum technique, made of small stones, abundantly covered with lime mortar. It was situated on the side of the stronghold, cut off from the western part of the island by a ditch, protected on the other sides by the river banks and by the ramparts.

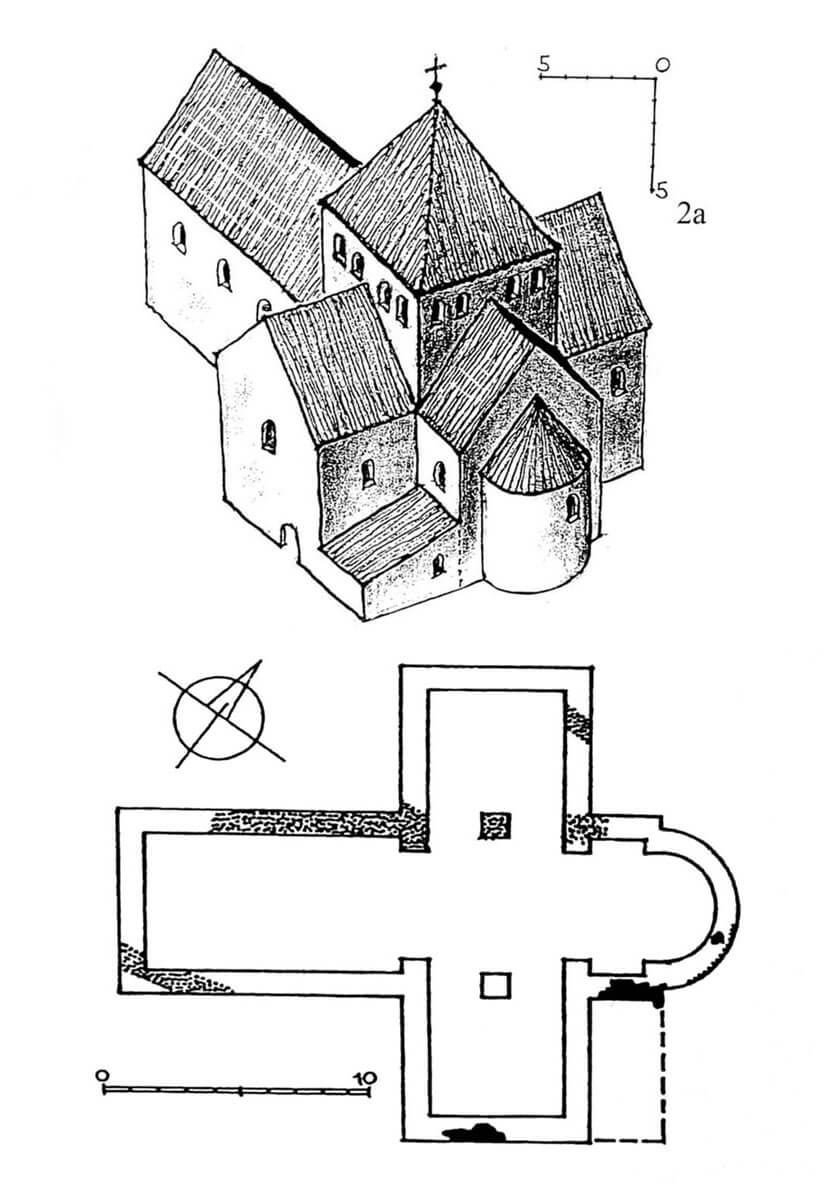

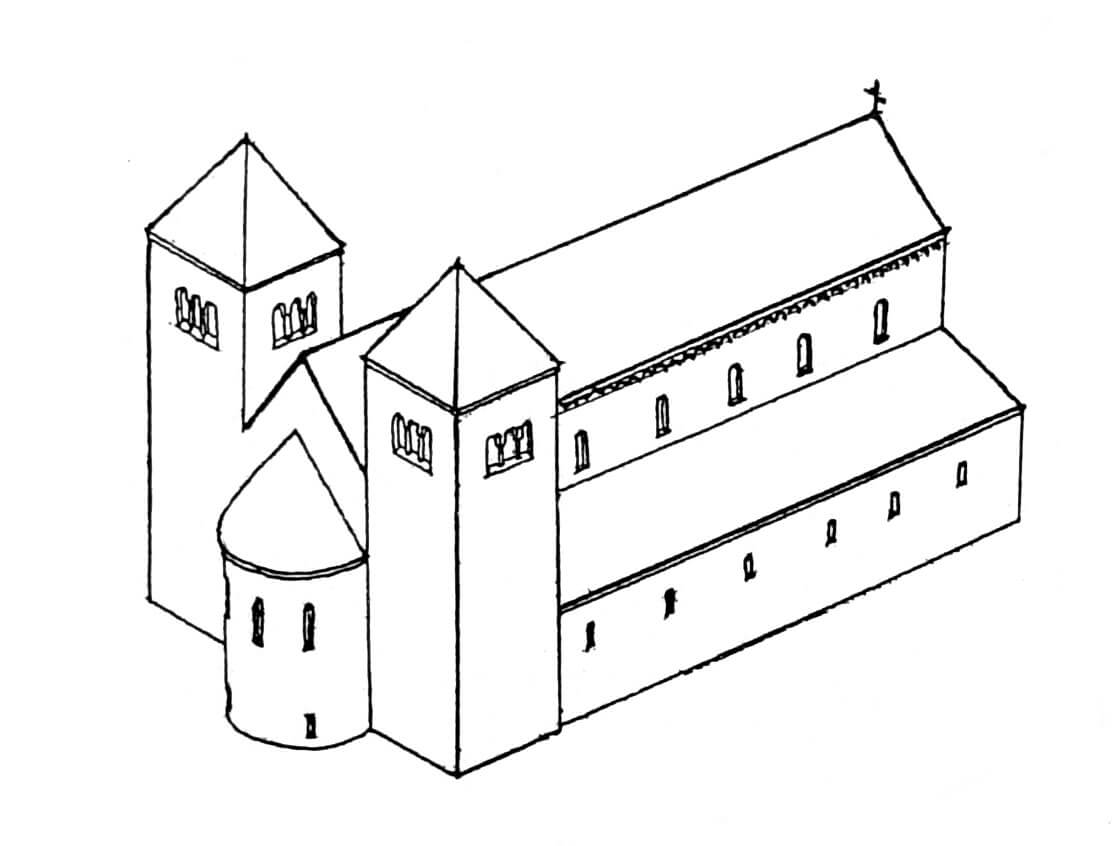

The cathedral from the third quarter of the 10th century was a pre-Romanesque building, built of granite bonded with lime mortar on the plan of a Latin cross, consisting of a nave resulting from the reconstruction of an older church, and an added transept and a short chancel ended with an apse in the east. The length of the nave was 23.7 meters, the transept had 18.7 meters and the width of the nave was 7.5 meters. The thickness of the foundation walls was up to 1.1 meters. The cathedral was probably covered with a shingled roof with an open truss uncovered from the inside or covered with boarding on the truss beams. Above the intersection of the aisles there was a four-sided, probably low tower, with windows necessary to illuminate the monumental, central part of the church, and the protrusion of the wall on the southern side of the chancel suggests that there may have been a small annex. The slope of the area on the eastern side of the church, in which later crypts were located, was characteristic. Inside, in both arms of the transept, there were galleries supported by single stone pillars. The pre-Romanesque cathedral in Wrocław showed a great resemblance to the church in Libice, from where the inspiration was probably came from and where the construction workshop may have come from.

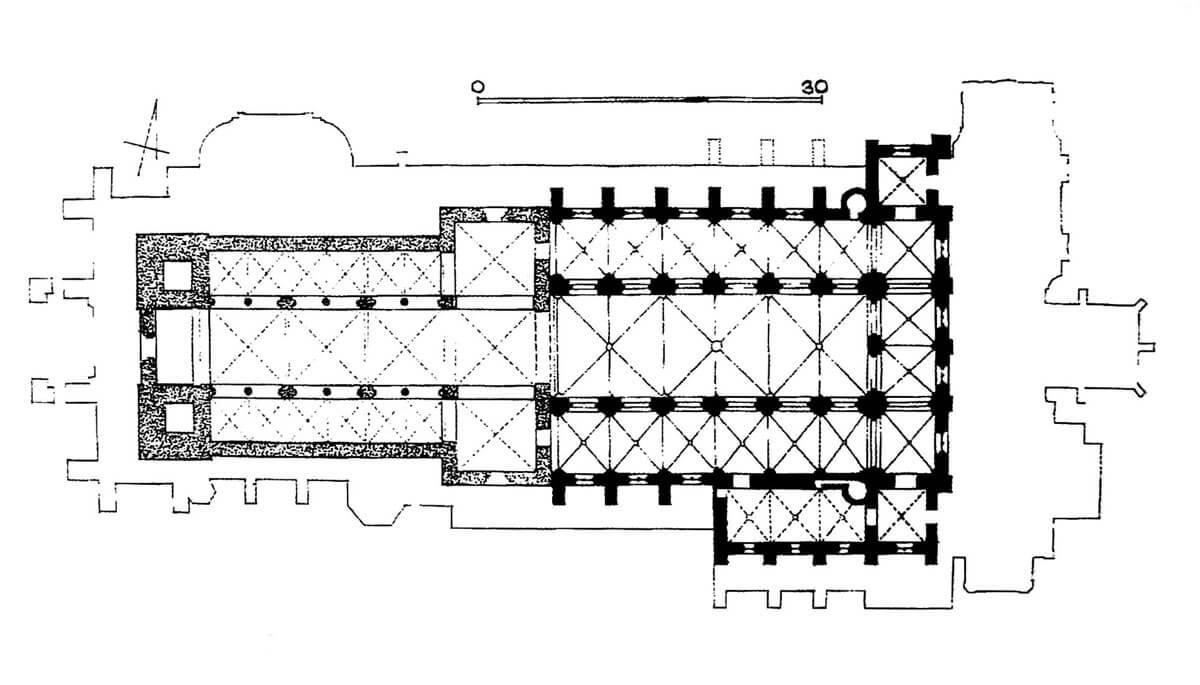

The early-Romanesque cathedral erected by Casimir the Restorer in the third quarter of the 11th century was slightly shifted to the north in relation to the previous church, because it was erected without using the lower parts of an older, demolished building. It was erected in the foundation part of large erratic boulders, unworked stones and material from the demolition of the pre-Romanesque church, bonded with clay. On this basis, walls 1.3 meters thick were created, made of granite stone slabs bonded by lime mortar and red sandstone used for architectural details. This cathedral was a three-aisle basilica without a transept with a single-aisle chancel closed in the east with a large apse, under which, 2 meters below the area at that time, there was a two-aisle, vaulted crypt with four pillars. On the sides of the chancel, there were two towers of unknown height, possibly with defensive features (they were closest to the fortifications of the stronghold), and on the opposite, west side, there was most likely towerless façade. The external dimensions of the building were about 34.5 meters long and 18.3 meters wide. Most probably, the church was not vaulted, but covered with a ceiling or an open roof truss, covered with shingles or slates from the outside. The cathedral had an advanced form and technique of detailing, as evidenced by the found relics, e.g. the base of a granite column, or the archivolt of the portal with a bas-relief basilisk or griffin.

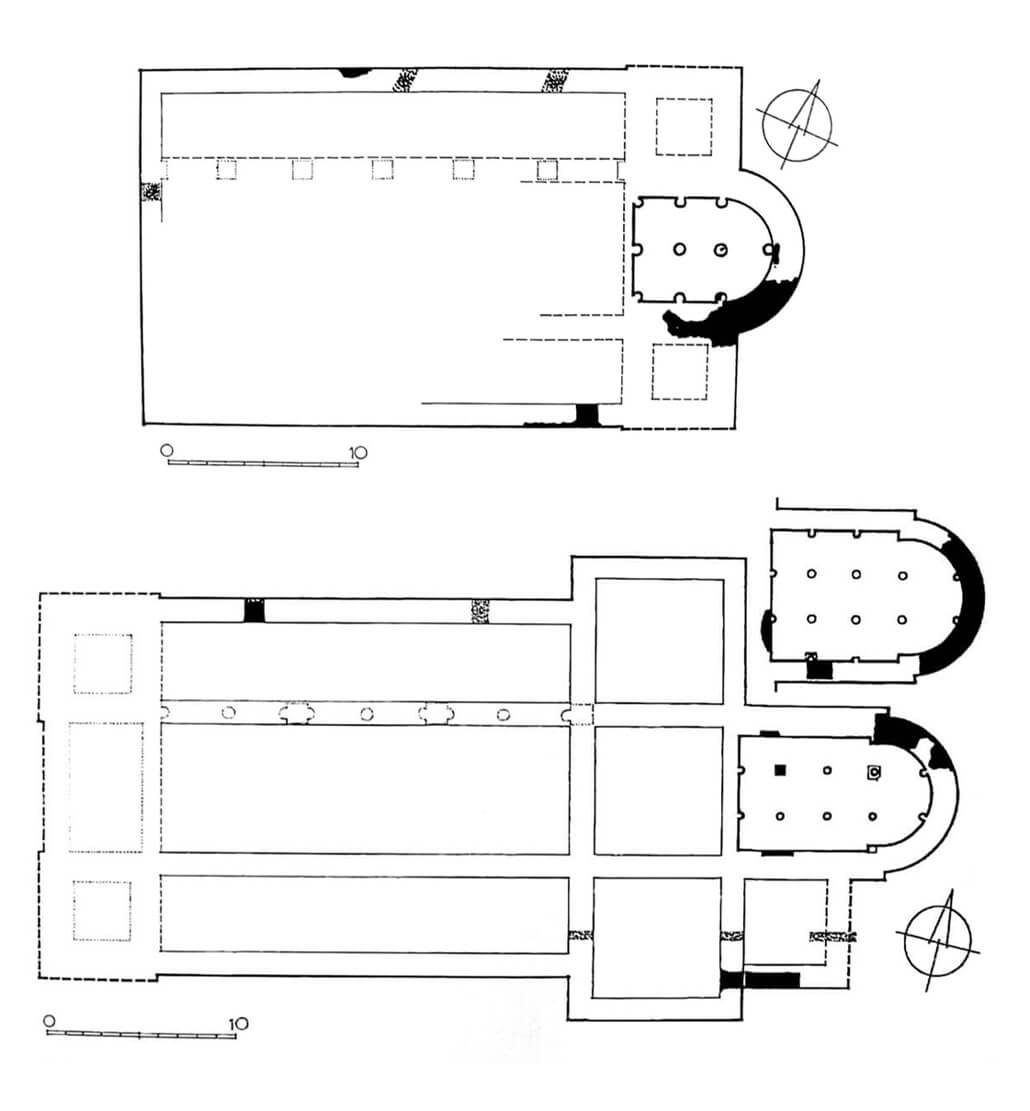

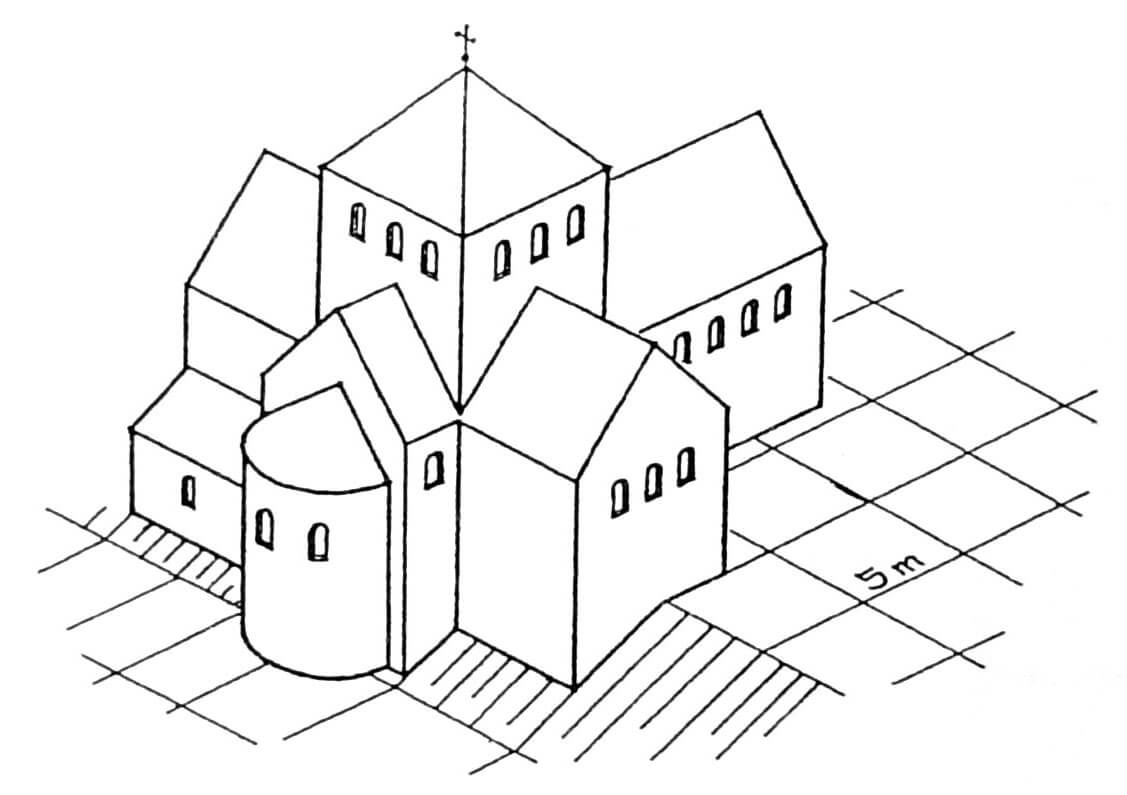

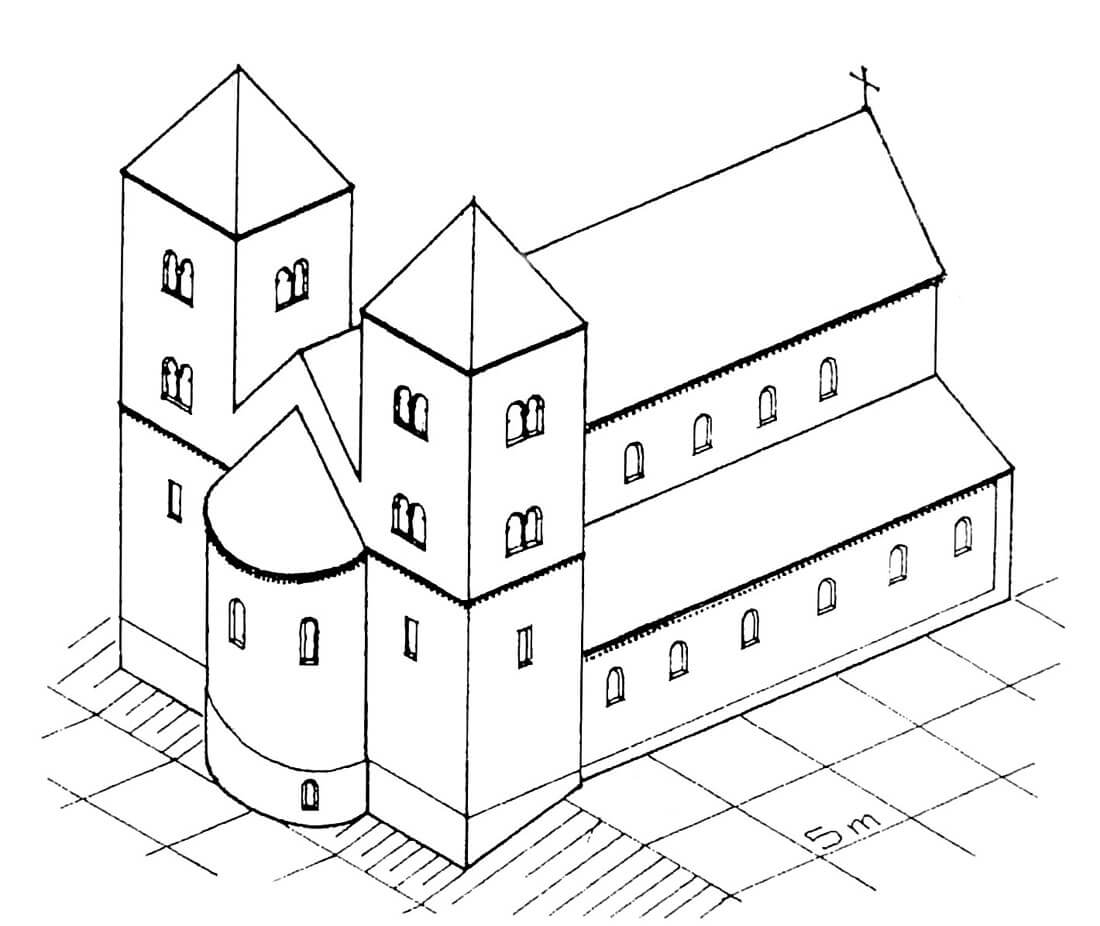

The Walter de Mallone cathedral from the second half of the 12th century was also a three-aisle basilica, but its walls were significantly thickened, the transept was added, the chancel was extended, and from the west, two new towers were erected, four-sided in the lower parts, octagonal on the upper floors (as shown on the bishop’s seal of Żyrosław II). The elevations were made of large ashlar blocks of white limestone and varied with numerous details of red sandstone. The apse, closing the church in the east, was divided by pilaster strips into three fields with two or three windows. At that time, the cathedral was 48.5 meters long and 24.5 meters wide, with the central nave being 7 meters wide, and the side aisles separated by pillars were 3 meters wide each. The stylistic features and the plan of the cathedral indicate the homeland of its founder – the country on the Rhine and the Meuse.

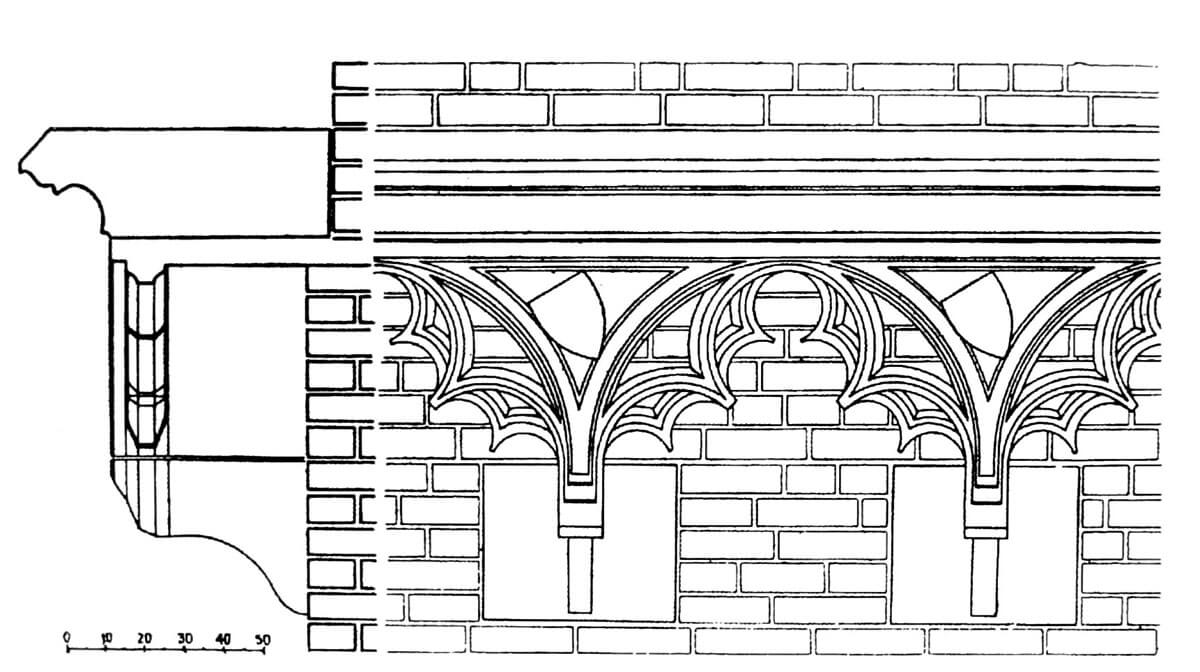

The interior of the aisles of the Romanesque cathedral was vaulted for the first time in its history. A new vault was also established over the crypt under the chancel, placed on new columns 37 cm in diameter (the previous ones had a diameter of 57 cm) with Corinthian heads. The façades of the church were covered with thin plaster from the inside and decorated in large part with paintings and with an unknown color setting. On the other hand, the external façades of the apse and the choir were decorated with a high frieze running under the eaves cornice, consisting of quatrefoil plots, embedded diagonally so that it were better visible from below. Such a solution, both its visual effect and the applied theme, was unique at the time.

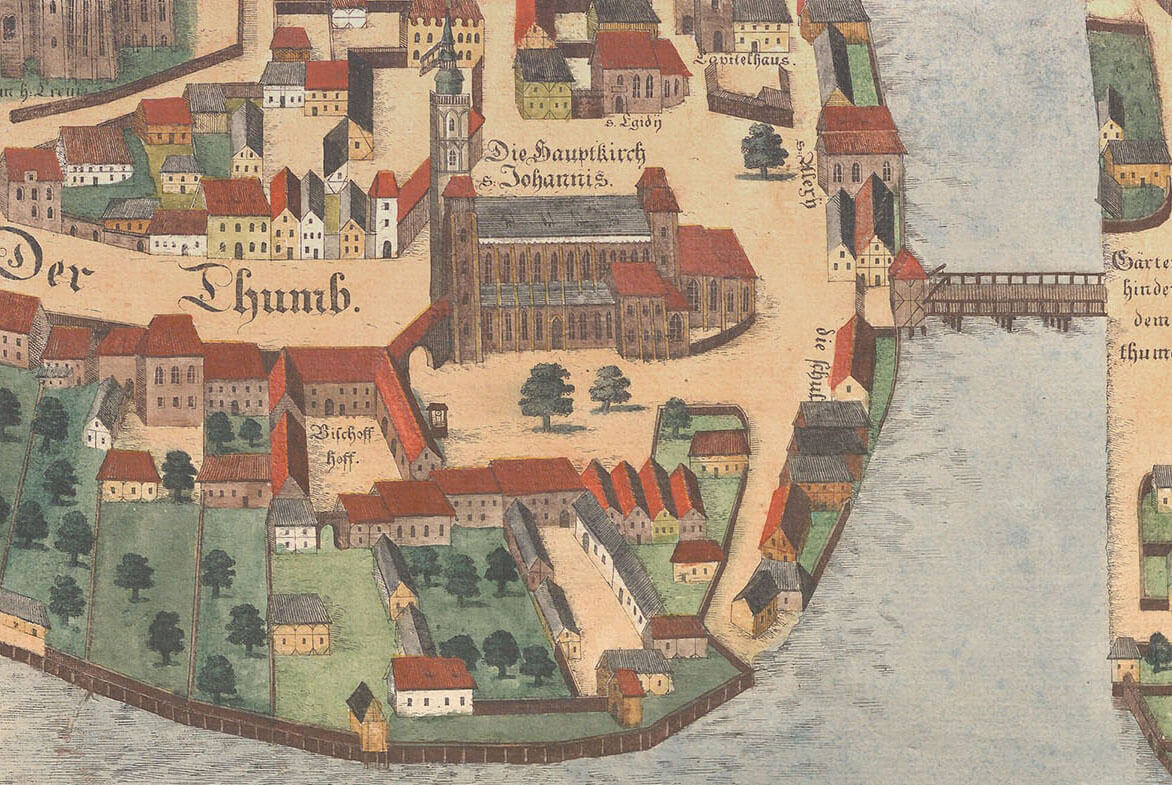

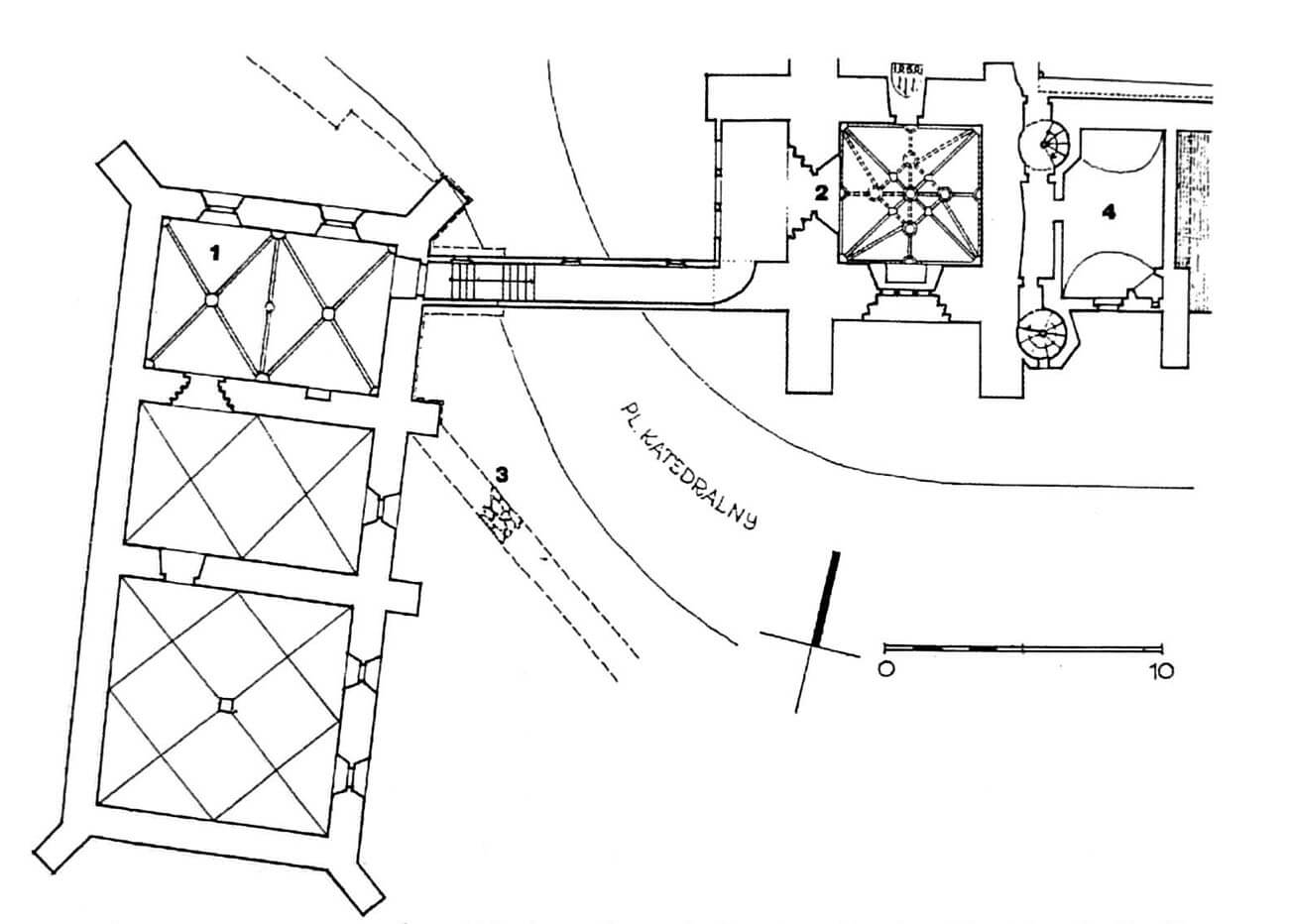

In the second half of the 12th century and at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, the cathedral, located in the eastern, slightly promontory part of the island and the stronghold, was probably separated by fortifications also from the ducal part of the castle complex on the west side. This rampart, together with the outer fortifications of the stronghold, separated a closed defensive complex filled mainly with sacral buildings and houses associated with it. At that time, numerous new buildings had to be built near the cathedral, because the energetic Bishop Mallone reformed the chapter, the school and most likely built his brick seat, located on the south side of the church. On the north side, in the first quarter of the 13th century, a brick church of St. Giles was erected, and shortly after, during Henry III times, the episcopal part was enlarged to the west towards the ducal castle. During this period, the old ramparts became a place for the construction of a brick defensive circuit as well as houses and economic buildings of the servants associated with the cathedral clergy.

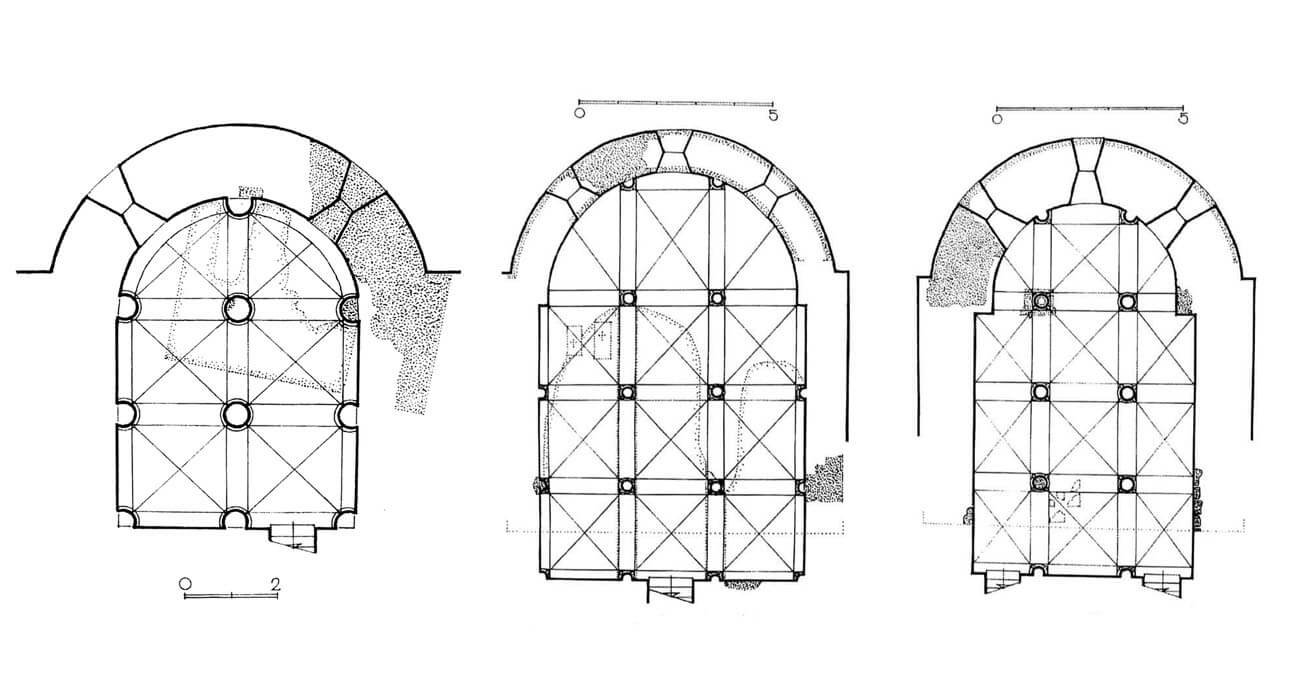

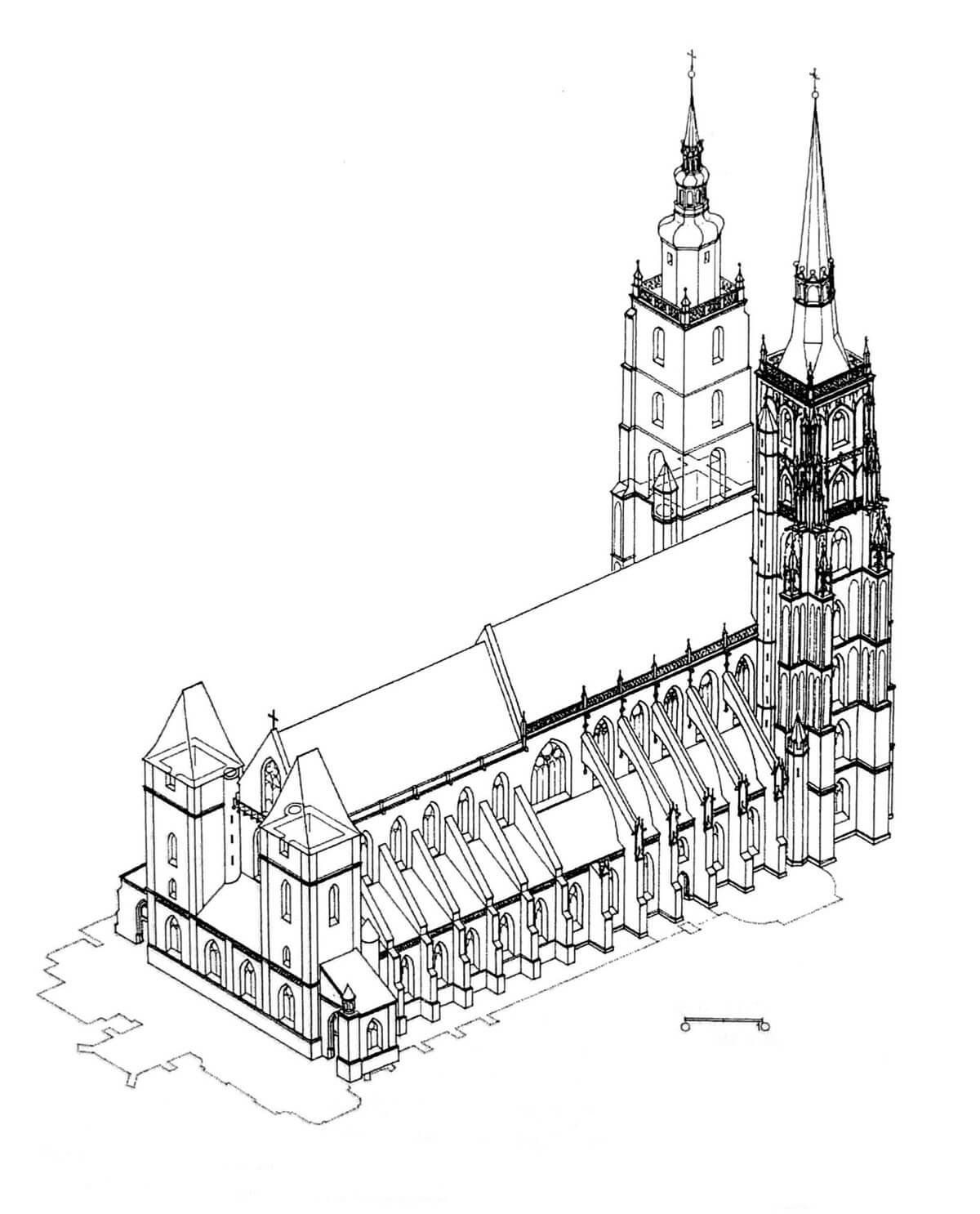

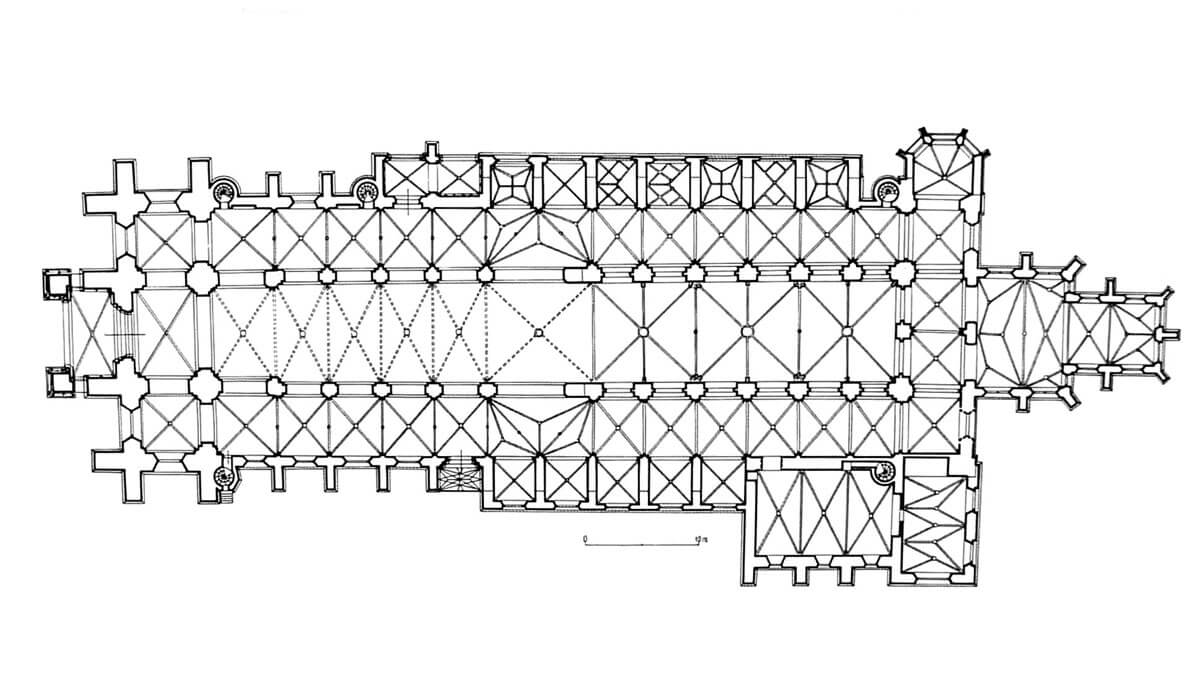

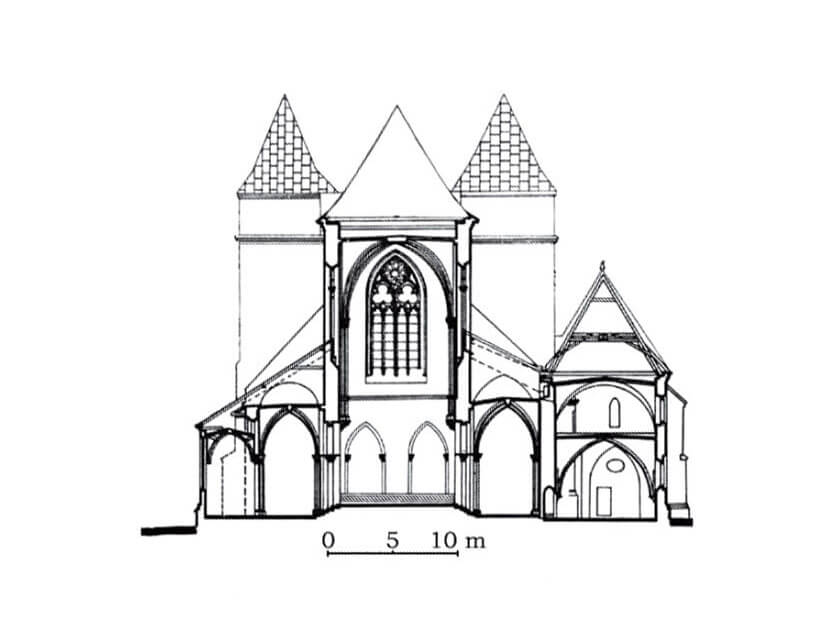

In 1244, the cathedral was expanded from the east by a straight closed brick choir with an ambulatory, adjacent to the old transept, with two low (never finished), four-sided towers over the extreme eastern corners. The new choir with an ambulatory, built in the style of early Gothic, took up the area almost three times longer than the old Romanesque chancel, reaching almost the height of the former stronghols’s rampart. The choir consisted of three square bays and rectangular bays of the ambulatory surrounding it on three sides, half the width of the choir. The chancel, as a priestly part of the cathedral, required additional rooms in the form of a sacristy or a treasury, which were planned in additional sideways, creating a kind of incomplete wreath of chapels similar to the Cistercian choirs.

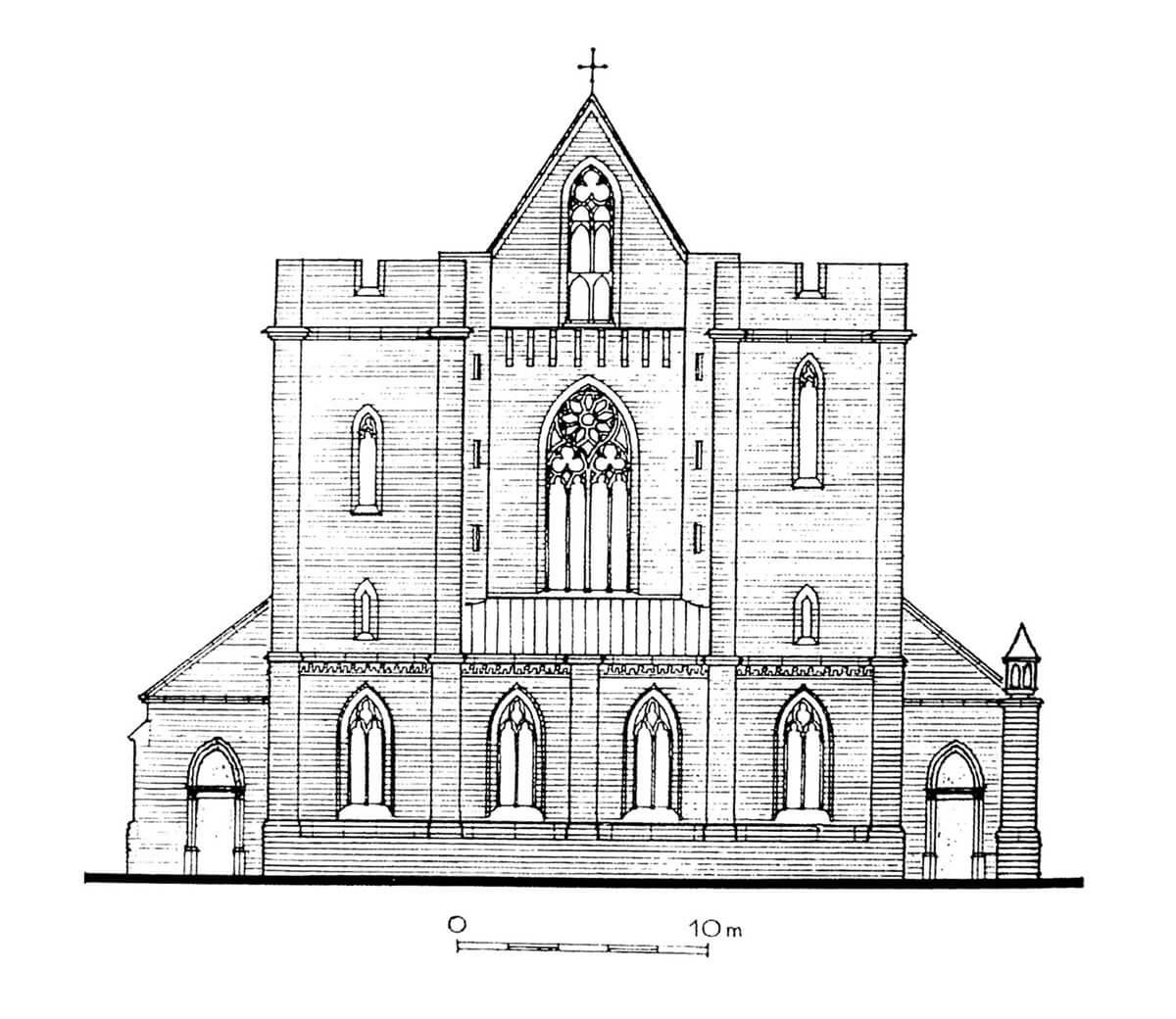

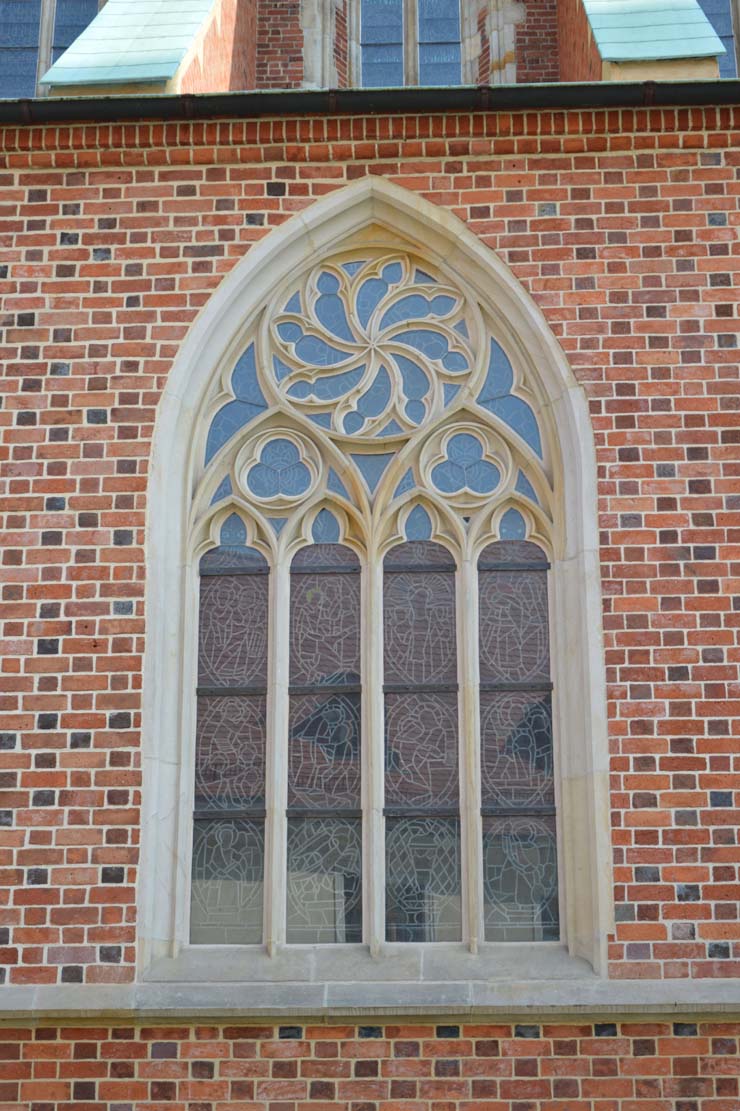

From the north and south, the walls were reinforced with buttresses, while the eastern façade was deprived of them. The wall of its central aisle above the lower ambulatory and between the towers was pierced with a large ogival window above which, interestingly, another large window was placed in the gable area, invisible from the inside, and therefore used only for decorative purposes. A similar role was played by the gallery connecting the corner towers with staircases, which, together with the two four-sided towers, meant that the eastern façade was not only the end of the choir, but until the rebuilding of the nave served as the main façade of the church.

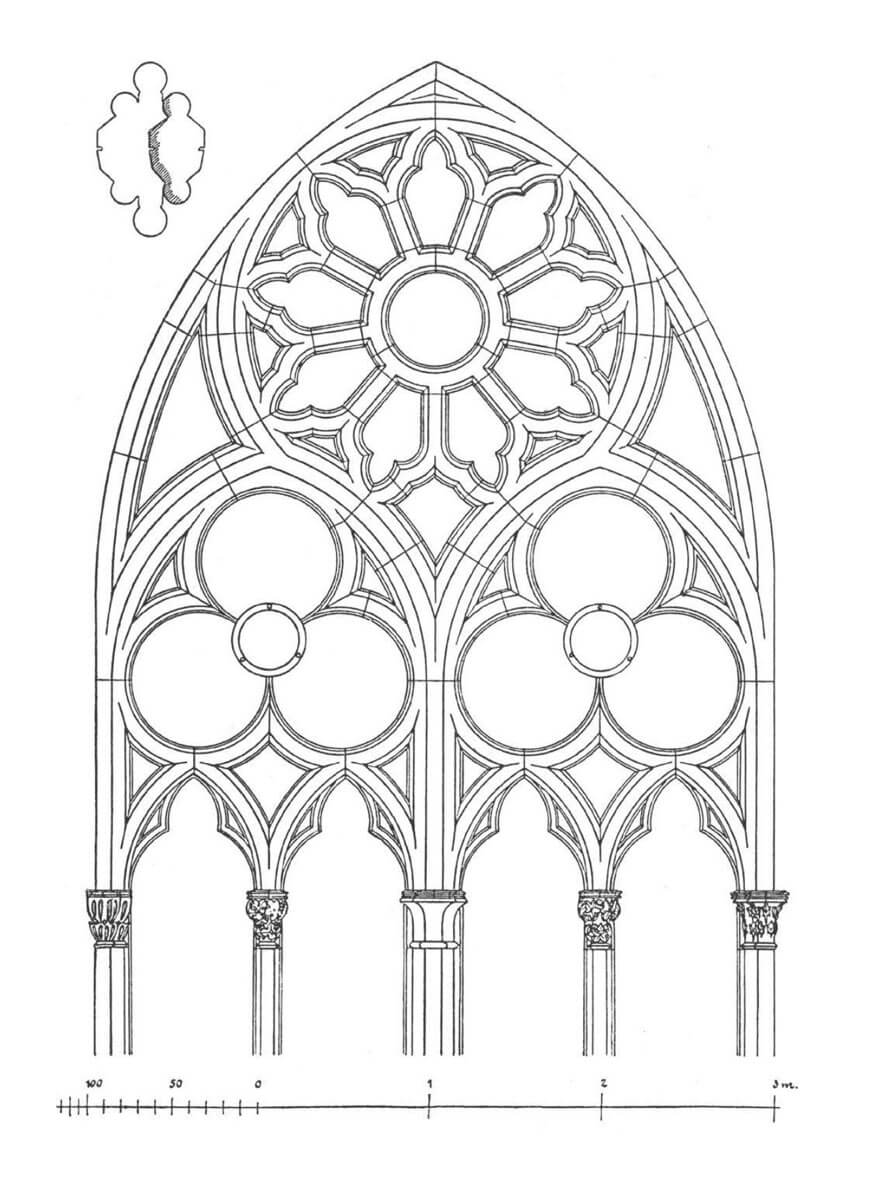

The great eastern window of the choir was distinguished not only by its size. Only it received a stone frame with a roller from the inside, while the side windows received brick jambs, moulded only with a steps. The greater width allowed for the building of a magnificent quatrefoil tracery instead of a two-light one, namely four ogival lancets, which were grouped in pairs, topped with trefoils and enclosed with larger pointed arches, and in turn a rosette was placed on them. The unusual composition of the tracery also gave its depth, visible in the varying thickness of the tracery and moulding, consisting of three superimposed layers. The first one was an ogival arch framing the whole, two ogival arches inscribed in it and the frame of the upper rosette, which was opened from the bottom, without a section between the pointed arches supporting it (which gave it a characteristic drop-like shape). The supports were made of single capitals in the extreme shafts and three in the middle one, as well as bases on high plinths. The second layer, which was the filling of the first one, was made of a repeated composition consisting of two small pointed arches supporting a trefoil. Next, the filling of the rosette created a radial arrangement of nine trefoil leafs around the central circle. The tracery of the eastern window at the time of its creation was an avant-garde work, a testimony to the far-reaching contacts and creativity of the architect who knew the latest achievements of French cathedral workshops and was able to develop them.

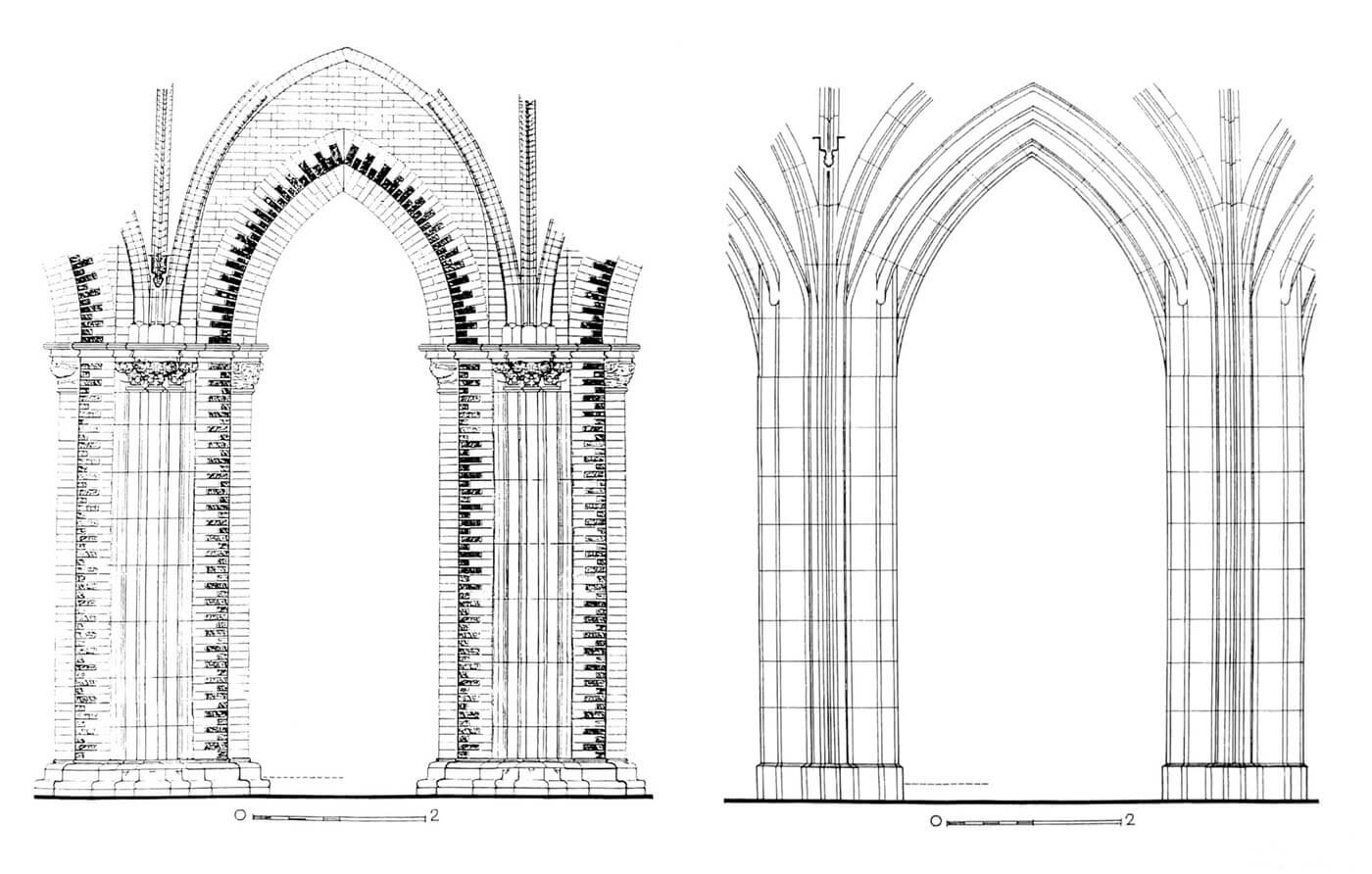

The early Gothic chancel in three square bays was covered with six-field vaults and cross vaults in the ambulatory, due to the use of which, for the first time in Silesia, flying buttress were used, carrying the weight of the choir vaults above the ambulatory to the side buttresses. However, it was still a quite primitive construction compared to the classic model used later in the nave. The brick arches, semicircular to the north and pointed to the south, were heavy and massive, and they transferred the pressure not to their structure, but to relatively low buttresses of the aisles, which could exert unnecessary side forces. The arches were probably covered with flat granite slabs and protruded outside only above the roofs of the ambulatory, without creating any openings. Their construction was unnecessary at the eastern wall of the choir, where the forces of high vaults were diffused by the heavy walls of the towers, and for the low vaults of the ambulatory, only pilaster strips were enough, used together with the towers to enrich the divisions of the façade.

Under the cornice of the ambulatory there was a stone frieze with motifs of flower buds, interrupted on the walls of the towers, while the whole was surrounded by a high pedestal. The walls were pierced by narrow and high pointed windows with quarter shafts in the jamb corners and with three-light tracery. Inside the chancel, no longer was granite used (except for the lower parts of the bases), but sandstone, easier to process and paint. The arcades in the chancel of the cathedral were closed up to a height of 1.7 meters with partitions, forming a support for the stalls in the choir and altars in the ambulatory. The square pillars were surrounded by a stone cornice at the height of the heads, above which there were vertical bunches of wall-shafts with an alternating rhythm of 3 and 5 pieces, due to the arrangement of the ribs of the six-field vaults. The wall-shafts were supported by corbels with a plinth zone and sculptural decorations. The brick walls of the chancel were left in their natural color and texture, only the joints were highlighted with white stripes. The fields of the vaults and window arches were covered with thin plaster, and in addition, the vaults could be decorated with gilded metal stars, placed in the holes left by the ropes supporting the working platforms. It is possible that the vaults were painted blue.

It is worth noting that during the approximately one hundred years of the construction of the Gothic cathedral, it was still necessary to take temporary and provisional measures. First, the Romanesque nave was used for 28 years during the construction of the early Gothic choir, then only the chancel functioned for half a century, until the nave was completed. Both phases were preceded by demolitions and the material obtained was used to build massive foundations, much deeper (about 5.2 meters) and wider (up to 2.8 meters) than the Romanesque ones. The process of dismantling and storing material, setting up scaffolding or creating excavations required a large amount of space, where numerous workshops, cranes and other devices were installed, also stored on old ramparts and by the river. The main construction site was to be located on the north side of the cathedral, next to the church of St. Giles, where, to the east of it, several buildings were erected from unused building materials: the multi-storey seat of the cathedral chapter, a school and hospital complex with the chapel of St. Alexius. There was probably less space to the south of the cathedral because of the episcopal court there.

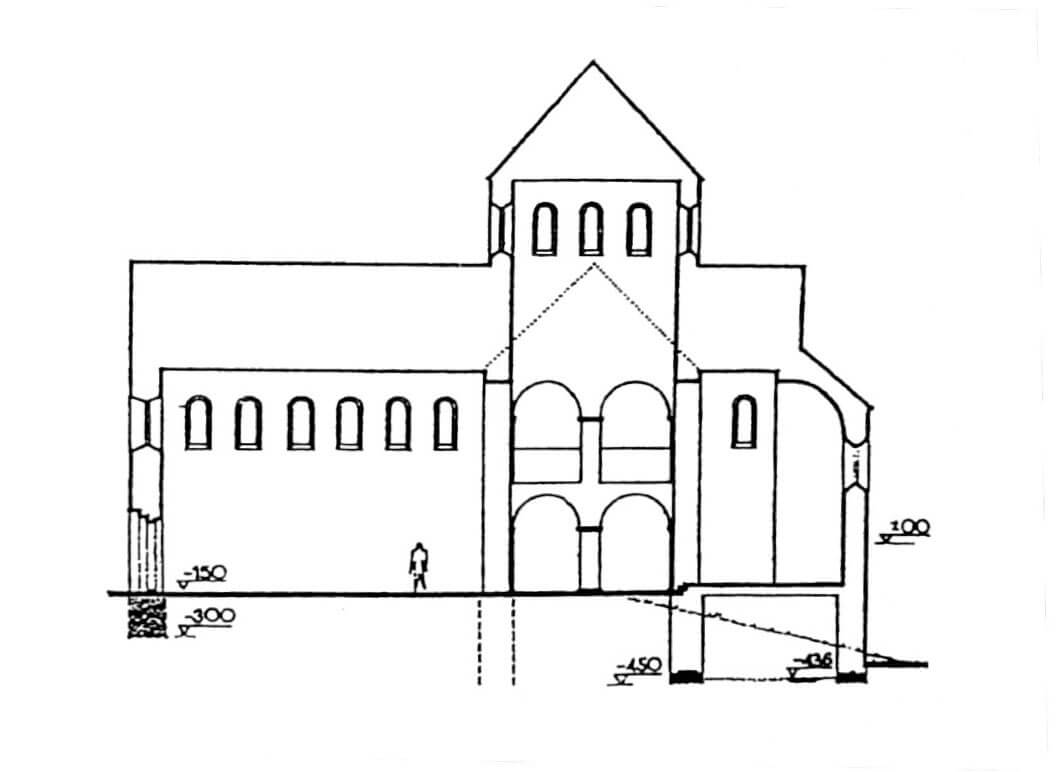

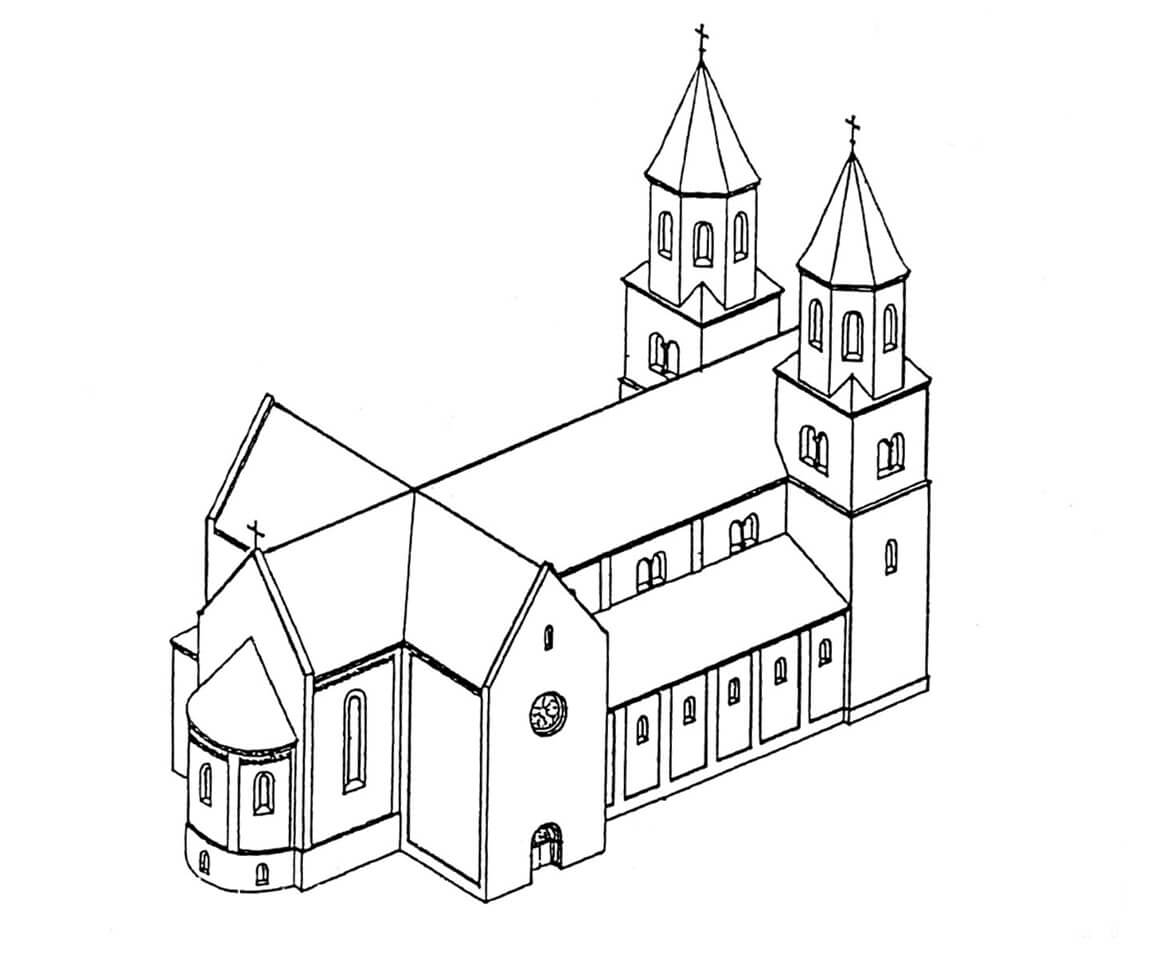

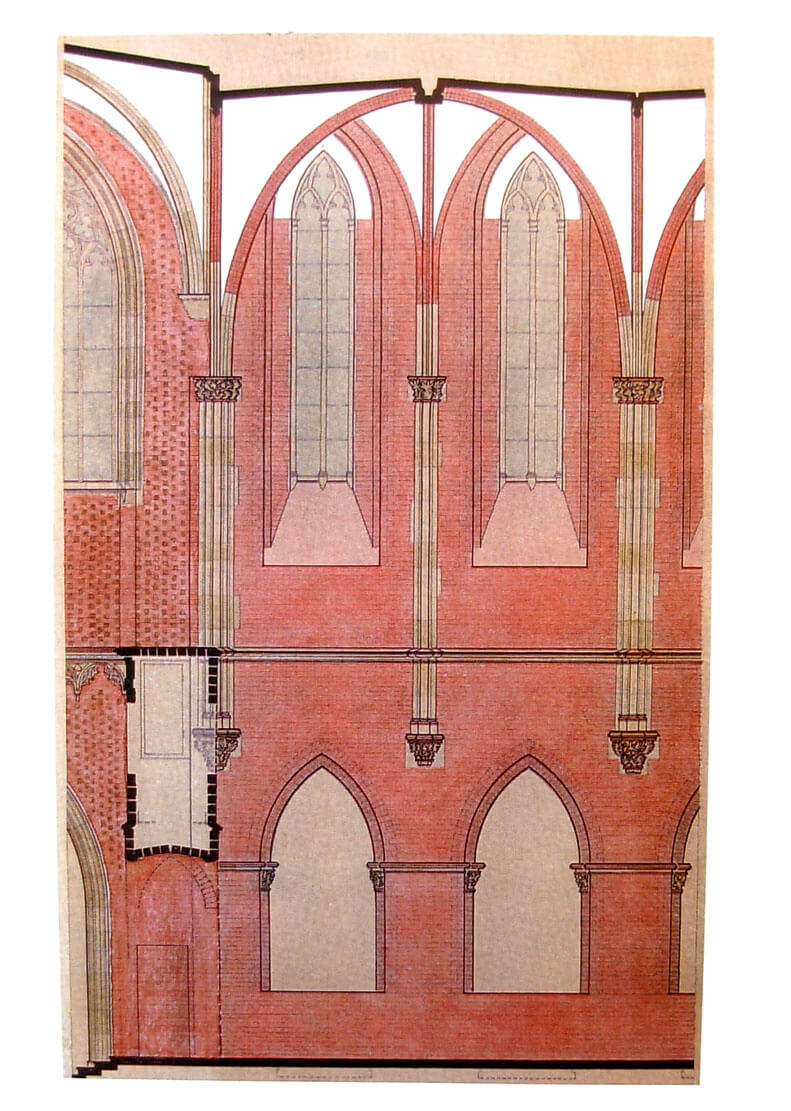

The Gothic nave from the first half of the 14th century received the form of a basilica with central nave and two aisles, six bays in length and an additional bay of the central nave located between two four-sided towers at the west facade. An interesting fact was the last bay of the central nave twice as wide, created in the place of the former Romanesque transept. The extreme western bay of the central nave with thicker walls resulting from the tower walls was also distinguished, as well as the first bay behind the towers, slightly wider than the remaining ones. This greater width was determined by the eastern buttresses of the towers and another pair of buttresses of the aisles. Difference resulted from the placement of stair turrets in the eastern outer corners of the towers, which forced the expansion of the adjacent bays of the aisles, so that windows could still be placed in them. As a result of the rebuilding, the Gothic cathedral obtained the appearance of a magnificent basilica, the length of which was 100 meters and the width of 44.6 meters.

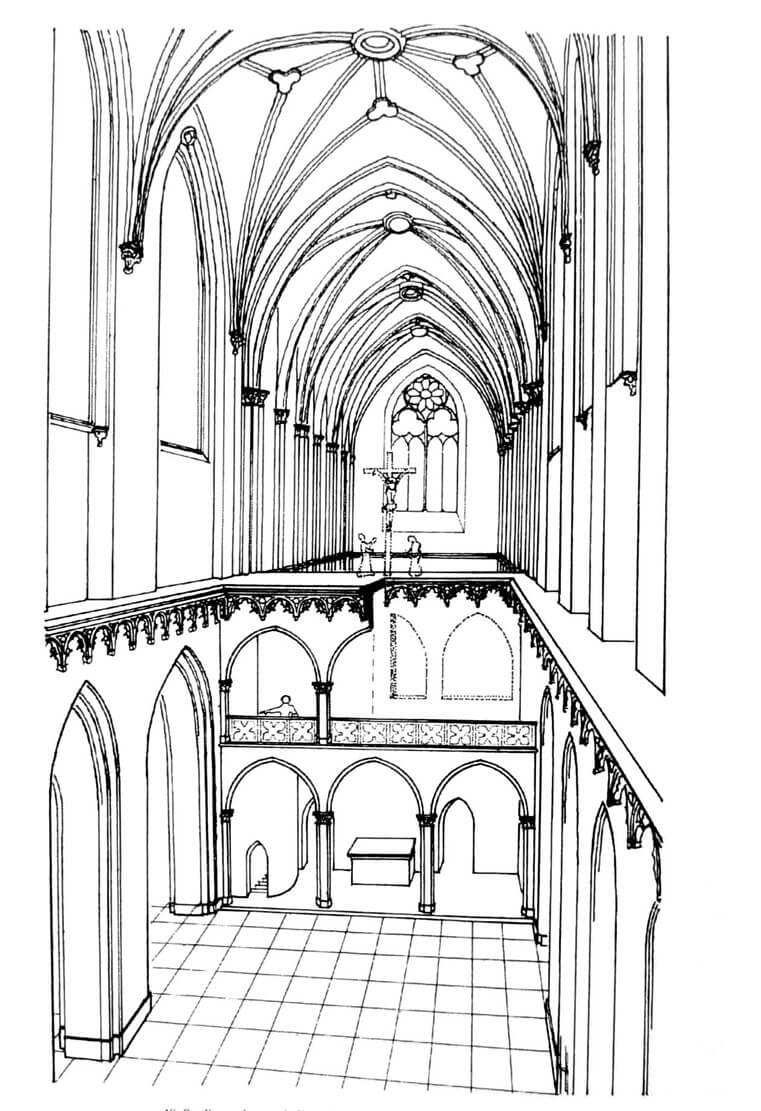

The contact between the new walls of the nave and the older walls of the choir was not perfect, as a result of which their planes jumped. The faces of both walls in the lower part missed towards the north, half a brick wide. However, due to the retraction of the face of these walls by half a brick in the upper part, the fault disappeared on the south side and doubled in the north. This evident error in marking the walls in the lower part of the interior of the church was obscured by the rood screen, but the upper part was left without masking. The rood screen separated the priestly part from the part of the church intended to lay people. It was preceded by a wider space of a pseudotransept (the aforementioned extended eastern bay of the nave), distinguished by a richer form of vaults in all three aisles.

The walls of the nave were smooth, devoid of vertical divisions of the plane, with faults over the lower zone of the pillars. The whole was surrounded by a horizontal cornice referring to the cornice in the choir, placed on a step above the inter-nave arcades. It consisted of arcaded projections forming a gallery along both side walls, connecting with the rood screen in the east and with the matroneum in the west. The support of the gallery was formed by a corbeled cornice composed of semicircular arcades with tracery, decorated at the joints with diagonal shields, although due to its small width it had no functional, but mainly decorative significance. Shallow window recesses were embedded in the clerestory, and the nave was covered with a rib vault and a stellar vault in the widened eastern bay. The side aisles had a wall-shafts without a capital zone, also with rib vaults and, for the first time in Wrocław, triple vaults in the eastern bays (probably modeled on the choir vault of the Kraków cathedral).

The ribs of the nave vaults were springin from the shafts without the capitals, except for the central bay between the towers, probably erected first, where the shafts were equipped with small capitals. It received an unusual form of a flattened conical consoles with an impost, intertwining with a roller shaft and adjacent concavities. Presumably, it did not impress the principals or builders, because all the other triads of shafts in the aisles and porches did not receive capitals, and the small capitals on the western wall of the under-tower pillars were covered with stylized foliage arranged in two zones. At the beginning of the 14th century the deprivation of the capitals from the shafts was a new solution, in the Wrocław cathedral one of the oldest in Silesia, with models probably coming from Austria or the Rhineland.

The construction of the fourteenth-century nave was carried out from west to east, while the narrower Romanesque nave, still placed in the middle of the church, was gradually dismantled. Probably for this reason, the arcades between the aisles in the first bay of the nave had a greater wall thickness and uniform moulding, springing without a capital band directly into ogival archivolts, and the arcades between the other bays of the nave were made less thick, approximately corresponding to the walls of the central part of the choir. The narrowing took place from the central nave side, thanks to the diagonal walls of the first pair of free-standing pillars of the nave. Their western half was created in such a way that it corresponded to the moulding of the under-tower piers, and the eastern half to the shapes of the other pillars of the nave, which was not the result of a change of plans during construction, but the dependence of the structure on the width of the walls of the early Gothic choir.

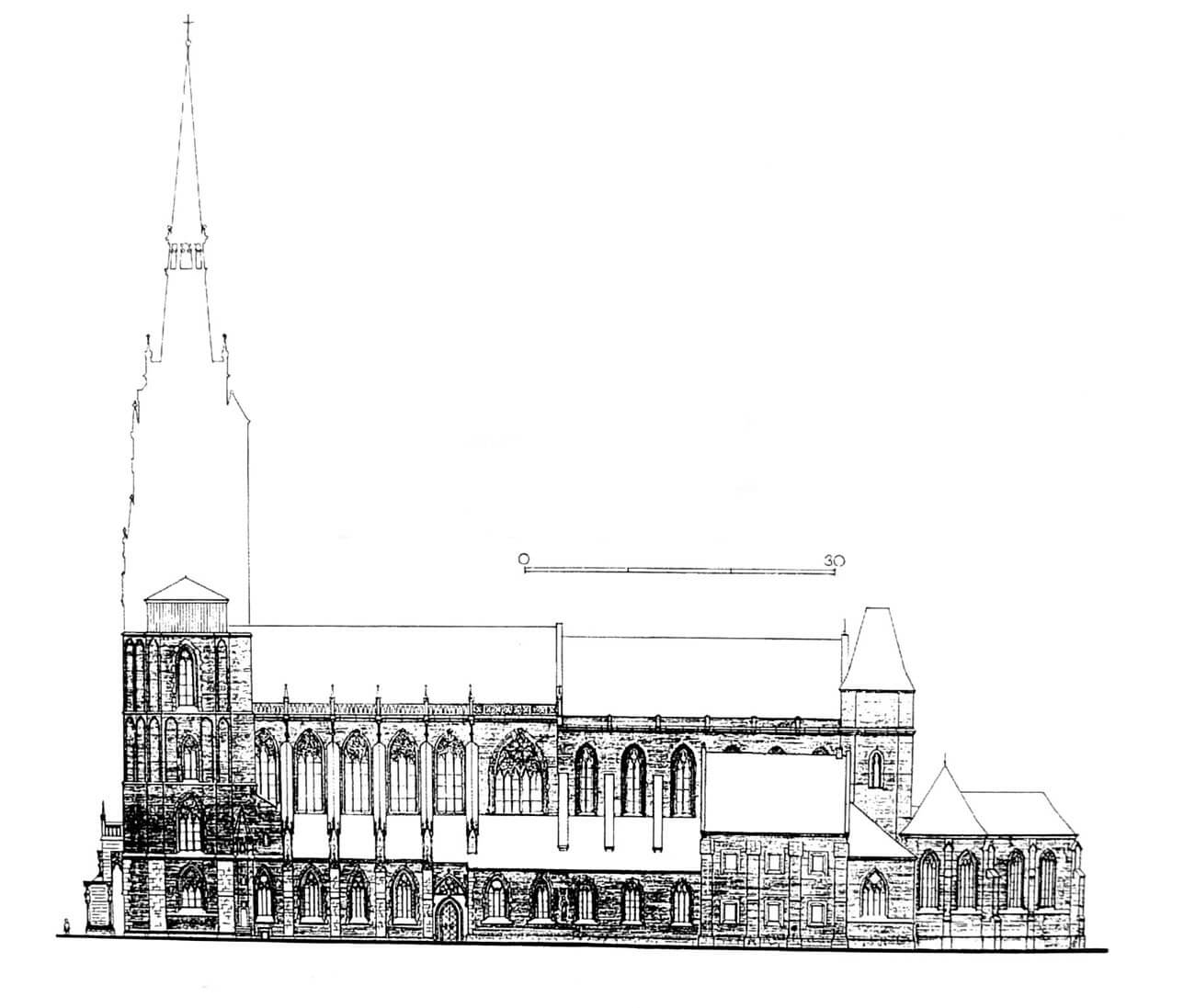

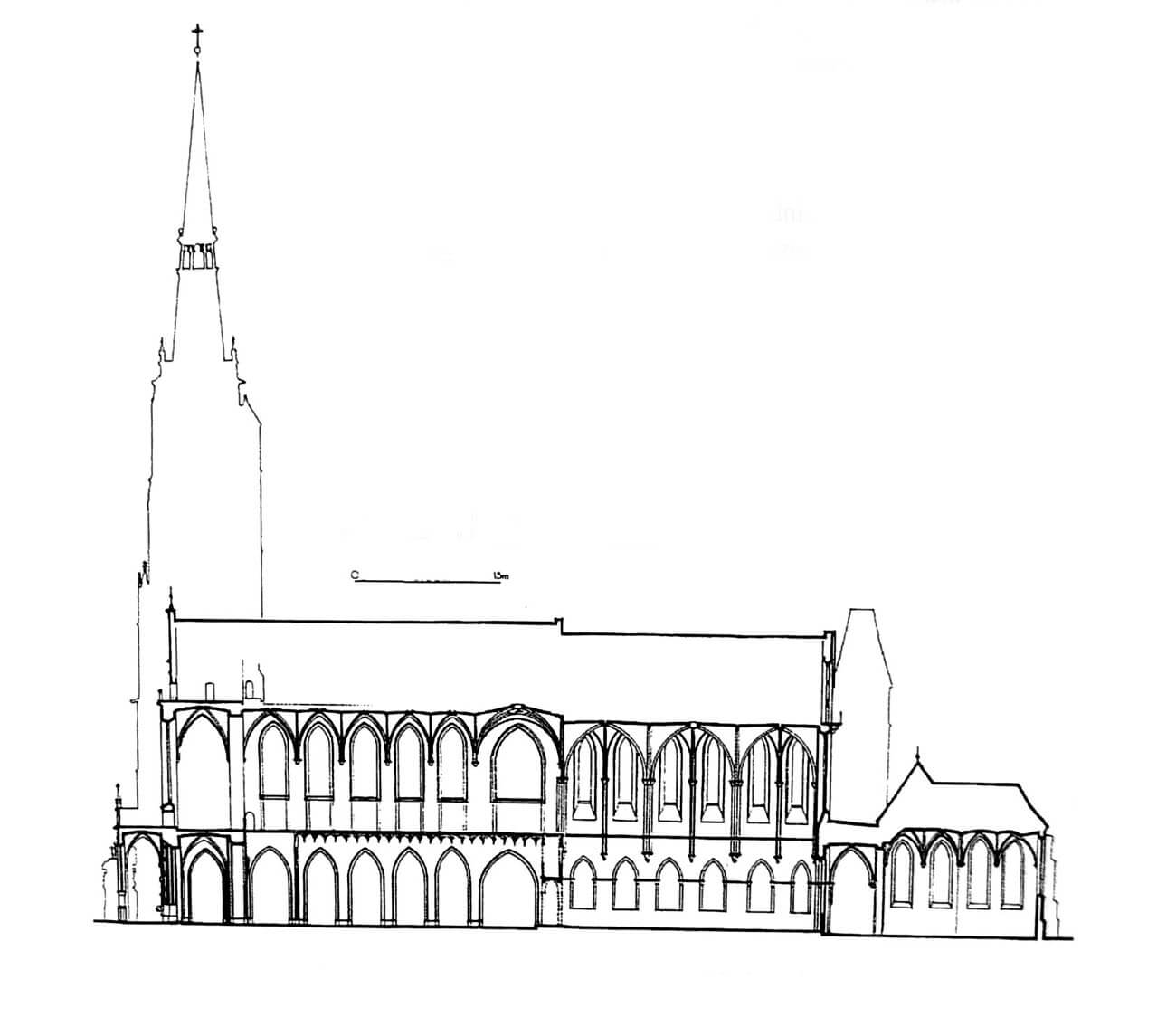

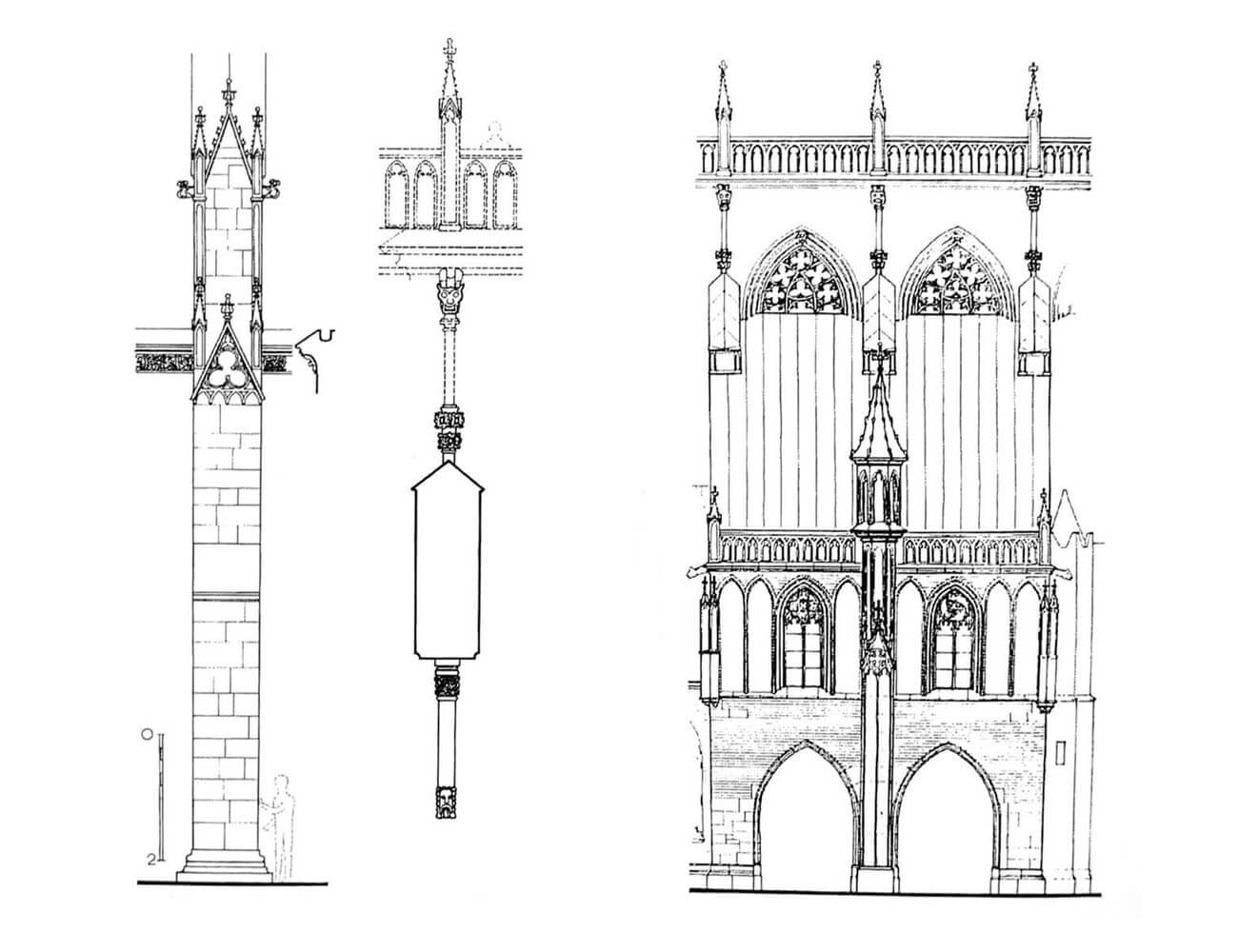

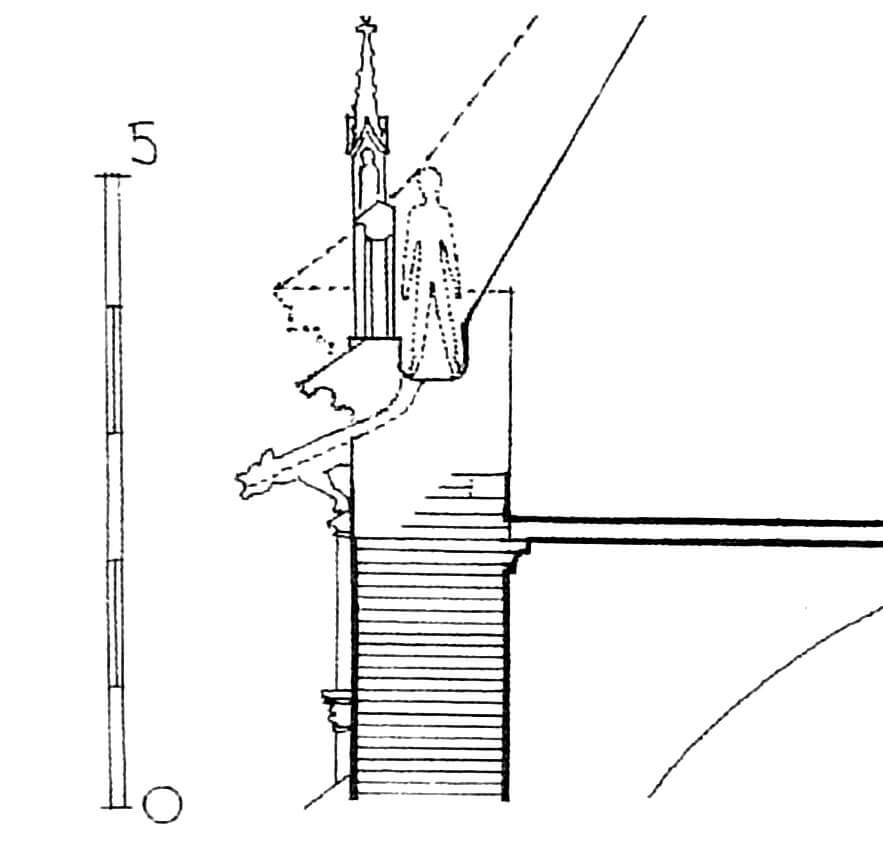

More details decorated the external façades of the nave, where, in addition to moulded elements, such as plinths, cornices, window jambs, buttress corners and portals, the stonework created pinnacles, crockets, gables, friezes and windows, as well as numerous sculptures in the form of masks, heads and mascarons in places such as corbels or window keystones. Contrary to the choir’s heavy flying buttresses, the nave features lighter and higher arches, more statically correct, forming buttresses in the lower parts of the aisles, topped with soaring gables and decorated with pinnacles. The rhythm of the high flying buttresses to a large extent enriched the external architecture of the cathedral, hiding simpler forms of the interior. The nave was very different from the older choir, about 1.2 meters lower, which was a challenge for an architect who wanted to aesthetically connect both parts of the cathedral. Two different rhythms of the nave and choir windows were separated by wider windows of the pseudo-transept, creating a link between them. From the tops of the flying buttress, decorative pillars supporting the gargoyles were led out under the cornice, which revealed the division into bays. In the nave part, above the cornice, there was an openwork stone balustrade, protecting the gutter (which removed rainwater), divided by posts crowned with pinnacles. Perhaps the balustrade above the eastern bay was distinguished by its form, and the extreme pinnacles created a more decorative element in the center of the facade. It is also possible that the bays of the pseudotransept were originally topped not with a balustrade, but with gables, masking the difference in levels of the choir and the nave.

The western façade shows differences in its gradual formation: two lower floors from the years 1319-1326 in the classical Gothic style, the third and fourth floors completed in the 40s of the 14th century, lighter thanks to the division of the walls with small blendes, enriched with gables and pinnacles, and the three highest storeys of the north tower completed in 1416 with rich stonework decoration on the facades and buttresses. They were vertical wall-shafts with gables and pinnacles, with windows with moulded jambs integrated into them, against the background of flat blende frieze decorations. On the buttresses, larger faults on the fifth floor were decorated with wall canopies supported by columns with figures of saints inside and shields on the walls. The late Gothic composition was enriched on the two top floors by a large number of crockets, topped with a cornice with gargoyles and balustrades. The culmination of the north-west tower was a high pyramidal dome, set on a terrace among four corner pinnacles, surrounded by a stone balustrade. From the square plan, the helmet went obliquely in the corners into an octagonal plan, forming a pyramid divided in the middle by an openwork gallery. The height of the helmet itself could be as much as 40 meters, while the height of the tower was 57.8 meters. The south tower remained unfinished until 1580.

The central part of the west facade of the cathedral consisted of three levels: the lower one with the main portal, a large window filling the wall above the gallery, and a gable covering the roof truss. The much thicker wall about 1.8 meters wide, resulted from the construction needs of the towers, gave the possibility of richly shaped portal and window jambs, and allowed for a significant step (1.3 meters) at the level of the upper cornice of the third storey, which in turn made possible to create a gallery in the wall (and not on the corbels as in the eastern façade). The gable was divided by a wide stone frieze and five pilaster strips into four fields, filled with pointed ornaments.

The western portal from the turn of the first and second quarter of the fourteenth century had a symbolic meaning, because bishop courts were held in front of it, sentences and anathems were pronounced. The pointed, moulded entrance was guarded by lions, griffins and basilisks symbolizing the outside world. The portal itself was mounted on a cut pedestal from which five bundles of moulding were led out, separated by slightly larger concaves. The first one from the outside was enriched with corbels and canopies for figural sculptures, which were also placed in two axes on both sides of the portal (in total there were to be 18 carved figures). The archivolt arch was additionally decorated with a wine flagellum.

In the years 1465-1468 portal was covered by a magnificent vestibule in the form of a portico protruding in front of the facade, covered with a cross vault based, apart from buttresses, on two thick pillars. In this way, a terrace surrounded by a balustrade was created above the portico, with a rich sculptural decoration consisting of numerous columns and figures of saints, placed on heads and consoles at the pillars, and originally also probably on the balustrade. Interestingly, the contract concluded with the master builder included the condition of using older elements, probably Romanesque or 13th-century, which could apply to the shafts of the columns and two lions carrying the bases of the columns on their shoulders.

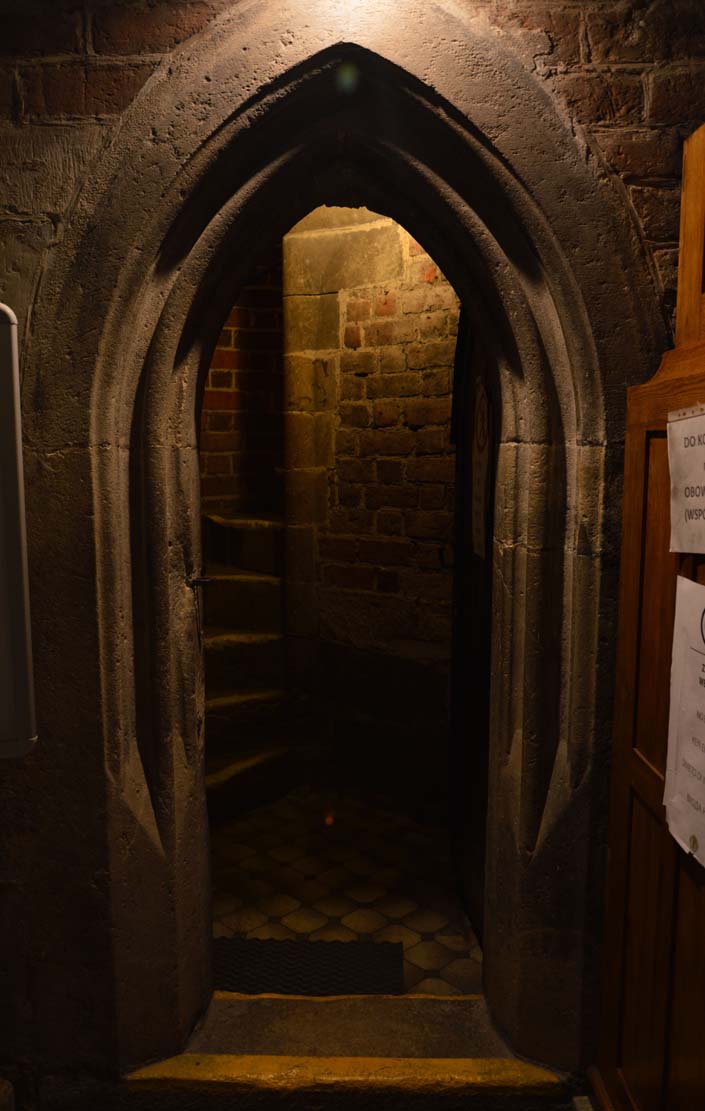

Earlier, a northern, two-bay vestibule was built, with the first floor containing the chapel known as the Imperial Choir. This chapel, connected to the interior of the aisle by two openings, created a kind of a gallery intended for listening to services rather than watching them. It was used by dignitaries, but, contrary to its name, probably not by emperors. The division of the vestibule into two parts was underlined in the center by a stone pillar, rising above the cornice and ending with a pinnacle – a lantern with an empty interior intended for placing lights in it (the so-called lantern of the dead). The stone interior of the porch and arcades were richly decorated and covered with polychrome, which does not exist today. This contrasted with the brick upper part, decorated with shallow blendes with a plastered background. In the Middle Ages, above the cornice of the porch with a drainage there was an openwork balustrade with pinnacles and gargoyles in the corners, and under the mono-pitched roof there was another floor, covered with a wooden ceiling, illuminated by windows in the side walls. It served economic purposes and was accessible through a spiral staircase in an added turret.

Since 1470, the southern entrance to the nave was preceded by a late-Gothic vestibule with a portal in the place of the window sill and the lower part of the older window. It was topped with a stellar vault, erected between two buttresses, and decorated with stone sculptural decorations (figural corbel, canopies with carved figures, crockets decorating the arcade). The portal itself obtained a relatively simple, but strongly moulded form with a pointed archivolt passing into the jambs without the use of capitals or consoles.

In the years 1354-1368, shortly after the completion of the nave, which reduced the importance of the eastern façade, the St. Mary’s Chapel, also known as the Small Choir, was built on its axis. Modeled on the English St. Mary chapels, it consisted of a wide two-bay nave and also a two-bay but much narrower chancel on the eastern side. This division influenced the applied vaults, mostly tripartite, but without ribs beetween bays, and two cross vaults on both sides of the chancel arcade. The interior, abundantly illuminated by two- and three-light windows with moulded frames, received a rich decoration of architectural sculpture. To the ambulatory of the cathedral, the chapel was opened with two chamfered arcades, while the arcade of the chancel, moulded in the archivolt, was based on two semi-octagonal pillars embedded in the corners with capitals with floral decorations. The vault corbels were created in the form of figural representations: in the chancel symbols of the Evangelists (ox, lion, angel, eagle), in the nave busts of a woman and a man, a sitting saint, an angel with a spear, a kneeling angel. The carved bosses show an angel, busts and coats of arms of Bishop Przecław, masks and floral motifs. From the outside, the chapel was fastened with buttresses with small gables, a plinth and a drip cornice.

In 1408, at the north-eastern choir tower, the chapel of St. John the Baptist was built, resulting from the transformation of the former 13th-century annex. Around 1517, it was rebuilt again by widening from the east and closed from the north with a three-sided wall with windows. The southern annex, similar to the northern one, was replaced in the middle of the 15th century with a rectangular canonical sacristy, built only from two walls (eastern and southern), touching the corner of the ambulatory and the buttresses of the older sacristy. It was covered with tripartite vaults. The main sacristy located on its west side, was rebuilt in the 15th century into a three-bay interior, enlarged twice as compared to the previous one, covered with rib vaults. From the south, it was supported by massive buttresses, and also in the first half of the 15th century, a second floor was added. The cathedral was complemented by two rows of chapels added in the 14th and 15th centuries between the buttresses of the ambulatory and the nave from the north and south. Of these, the chapel of St. Anna adjacent to the northern vestibule with the vault with a hanging boss stood out, and a chapel with a Romanesque figure of St. John the Baptist, allegedly erected on the “holy spring”, the site of the former pagan well functioning at the church since the 10th century.

Inside the first floor of the south-west tower, the chapel of St. Andrew was created. It was established in 1464 by building a spectacular stellar-net vault with sculptural decorations of polychrome corbels and bosses. It was also distinguished by the connection with the nearby bishop’s court by means of an overhanging porch, placed on a strong arch over the passage between the two buildings. Next to the chapel there was a small room with a fireplace, which was a room for a bell ringer or a guard. On the outer face of its gable wall, at the interface with the buttress of the tower, there is a sculpture of unknown meaning, showing a human face with an expression of anger and mouth open to scream.

Current state

The Wrocław cathedral is today an exceptionally valuable monument, in fact the only example of a Western European form of great Gothic architecture of the 13th / 14th century in Poland. Unfortunately, due to many devastating fires, storms and warfare, as well as early modern transformations, it did not survive in its original condition. The collapsed Gothic helmet of the north-west tower destroyed the Gothic vaults of the nave, and as a result of the fire, the vaults above the choir collapsed. The sixteenth-century vaults erected in their place were clearly poorer, lower and more flattened, and in addition they were destroyed in 1945. Unfortunately, the Gothic eaves cornices of the nave and the choir with balustrades and decorative gargoyles, which together constitute the main aesthetic value of the side elevations, have not survived. Most of the traceries of the central nave windows were also destroyed. In the 17th and 18th centuries, part of the Gothic church was covered with baroque chapels, which especially influenced the appearance of the cathedral from the east. The opposite, west facade and west towers were badly damaged in 1759, and the western gable had to be demolished after the fire. Virtually the entire cathedral was burnt down in 1945. Inside, the Gothic rood screen was removed in the early modern period, and nothing has survived from the once rich, medieval furnishings of the church. The last remaining elements in the form of parts of the stalls were destroyed during the Second World War.

bibliography:

Adamski J., Uwagi o chronologii budowy i stylu czternastowiecznego korpusu katedry wrocławskiej [w:] Katedra wrocławska na przestrzeni tysiąclecia. Studia z historii sztuki, red. D. Galewski, R. Kaczmarek, Wrocław 2015.

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. T. Mroczko, M. Arszyński, Warszawa 1995.

Bernaś A., Czternastowieczne portale główne w kościołach wrocławskich, “Architectus”, 1-2 (17-18), 2005.

Jarzewicz J., Kościoły romańskie w Polsce, Kraków 2014.

Jarzewicz J., Maswerk chóru katedry – awangardowa forma w architekturze XIII-wiecznego Wrocławia, “Architectus”, 1/53, 2018.

Małachowicz E., Architektura wczesnośredniowiecznych budowli katedry wrocławskiej [w:] Początki architektury monumentalnej w Polsce, red. Janiak T., Stryniak D., Gniezno 2004.

Małachowicz E., Katedra wrocławska. Dzieje i architektura, Wrocław 2012.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.