History

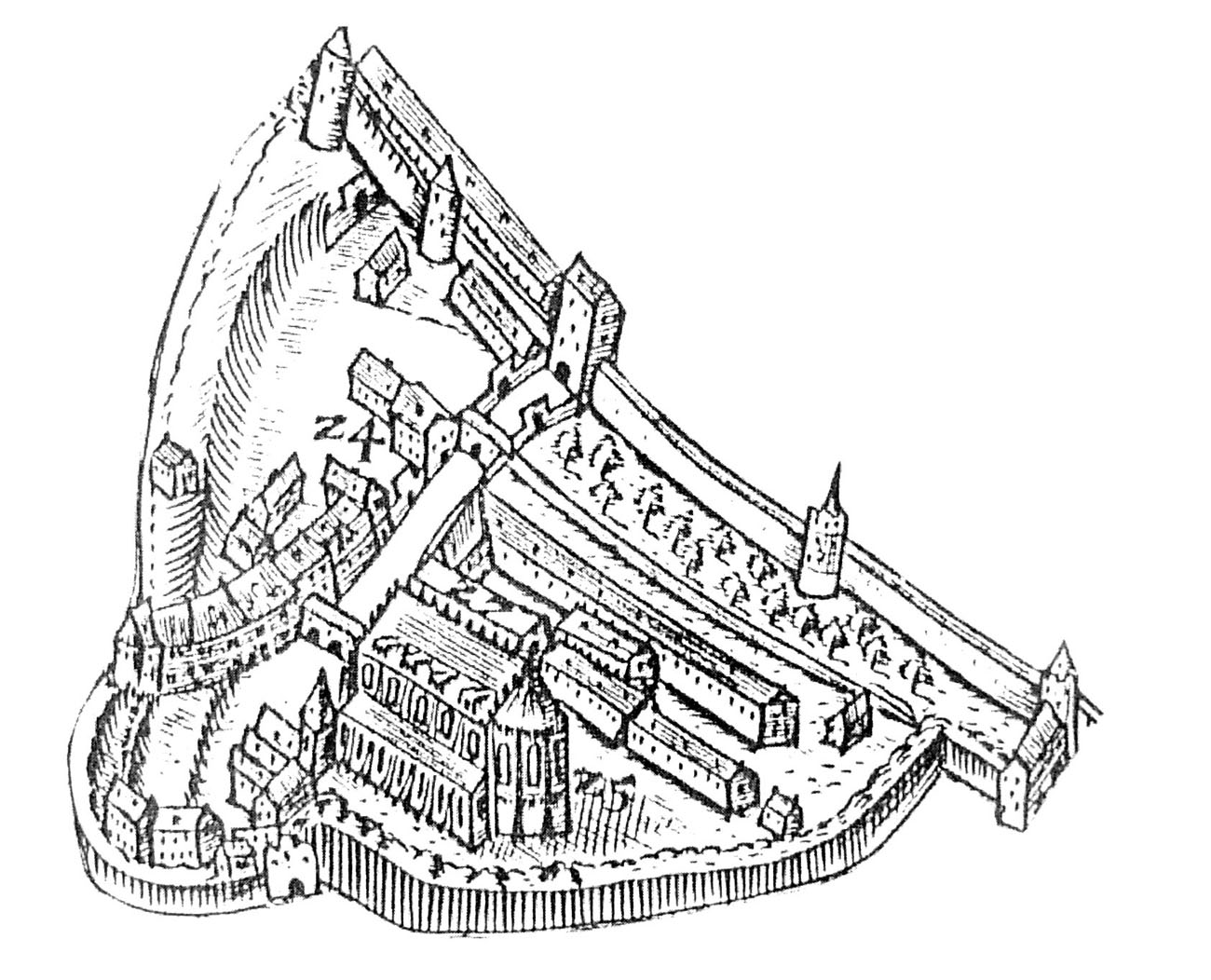

In 1273, the land in the southern part of Wrocław (among others, the village of Gaj) became the property of the Knights Hospitallers, and in 1319 the city council entrusted the monks with the care and management of the Corpus Christi Hospital, which was established in the first decades of the fourteenth century. Related to it was the chapel, mentioned in the document from 1317-1318, concerning its foundation in front of the Świdnicka Gate, in the area adjacent to the cemetery, where epidemic victims were to be buried.

The church of the Corpus Christi was first mentioned in 1351, while in the times of commander Jan Oczko (1360-1390), written sources noted the erection of a covered porch, which connected the church with the commandery of the order, located on the opposite side of Świdnicka street. Thus, probably around the middle of the fourteenth century, the perimeter walls of the church were erected, which replaced the older chapel, then too small for the growing group of monks and increasing number of patients. In the second half of the fourteenth century, the walls of the central nave were raised and it was decided to enlarge the church by extending it eastwards. This was probably due to the exemption of the Knights Hospitallers in 1366 from the obligation to take care of the hospital and thus to have more financial resources. The main work was completed by around 1410, but finishing works continued until about the middle of the 15th century (in 1447 a new portal in the sacristy was made, and in 1450 a source reference described the church as in use).

In 1540, the commandry of the Knights Hospitaller was taken over by the municipal authorities by the decision of Emperor Ferdinand I. The ruler ordered Lutheran services to be held in the church for eight years. Later, the function of the church changed from sacral to storage, because it was a warehouse for salt, grain and later stables. This led to the destruction of the medieval equipment and the disperse of the library’s book collection. The monks returned only in 1692, after Bishop Francis Louis bought the building and returned it to the Catholics. After eight years, the church was re-consecrated, but during the renovation, its interior was transformed in the Baroque style.

In 1749 the church was badly damaged during the explosion of the Powder Tower. Perhaps for this reason, from 1758 to 1763, during the Seven Years’ War, it served as a grain warehouse. Despite of subsequent costly renovations, it was again occupied and devastated by the city’s defenders, first in 1778-1790, later in the face of the approaching Napoleonic army in 1805. In 1826 the church was taken by the Prussian state and at that time the porch to the former commandry was demolished. From the 1830s, further renovations and repairs of the church were carried out, which lasted almost half a century. In 1875 a neo-Gothic porch was created, and from 1927 to 1931 further renovations were carried out. The siege of Wrocław at the beginning of 1945 caused great damages to the church: some of the tracery and walls were crushed, fragments of the central nave’s vault collapsed, partly also the side aisles vaults. After the war, temporarily covered with a roof, church was rebuilt only in 1955-1962, and then in the next stage in 1967-1970.

Architecture

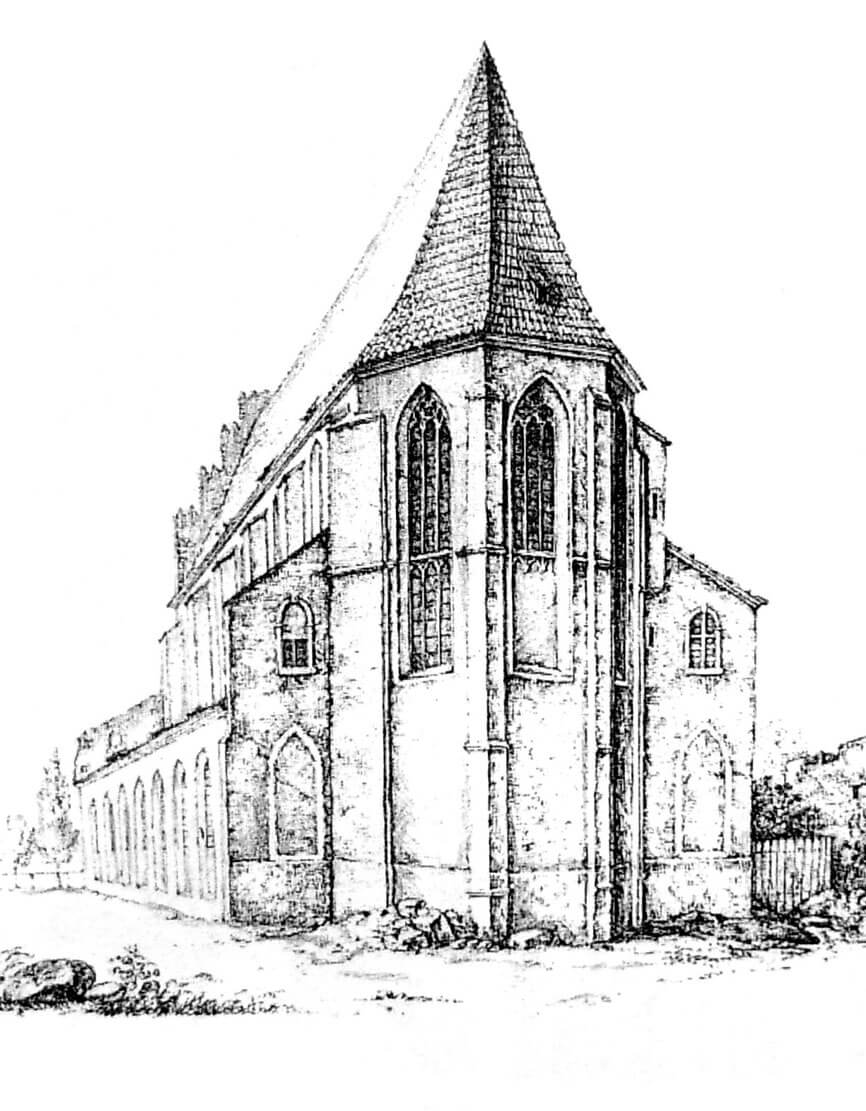

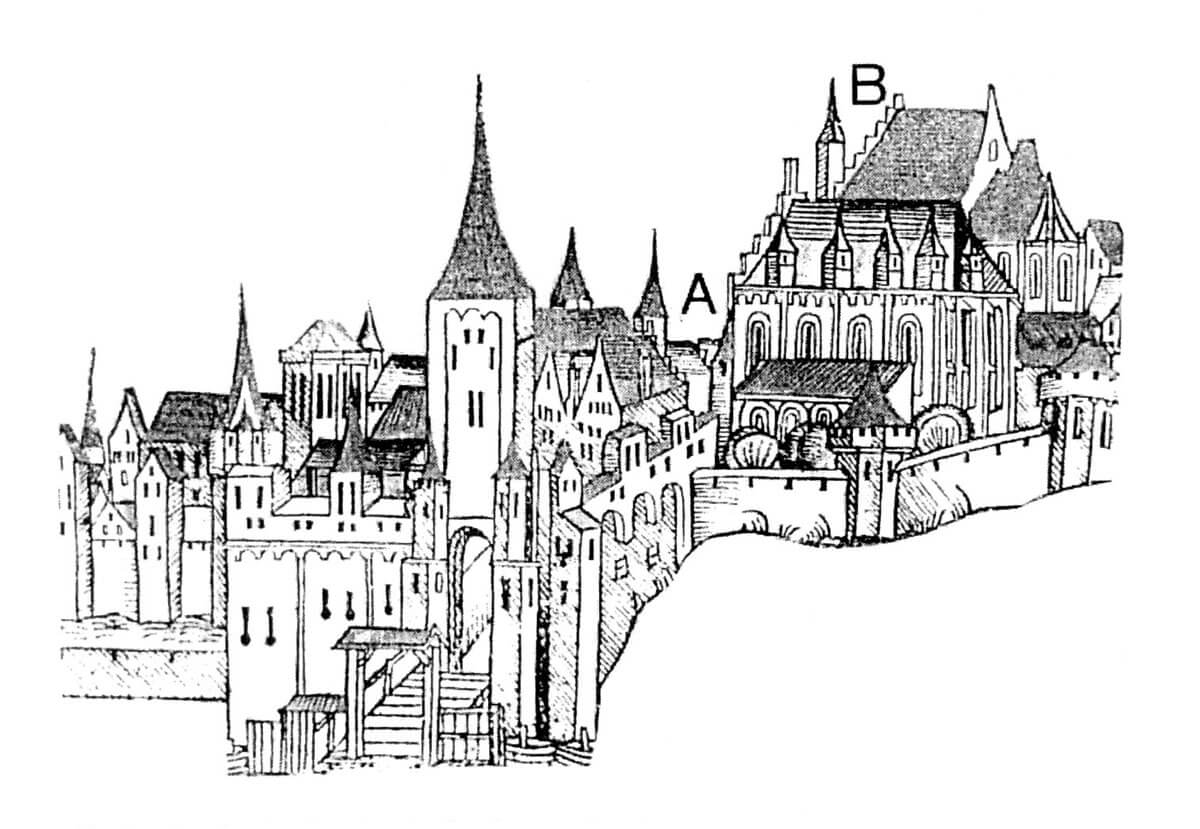

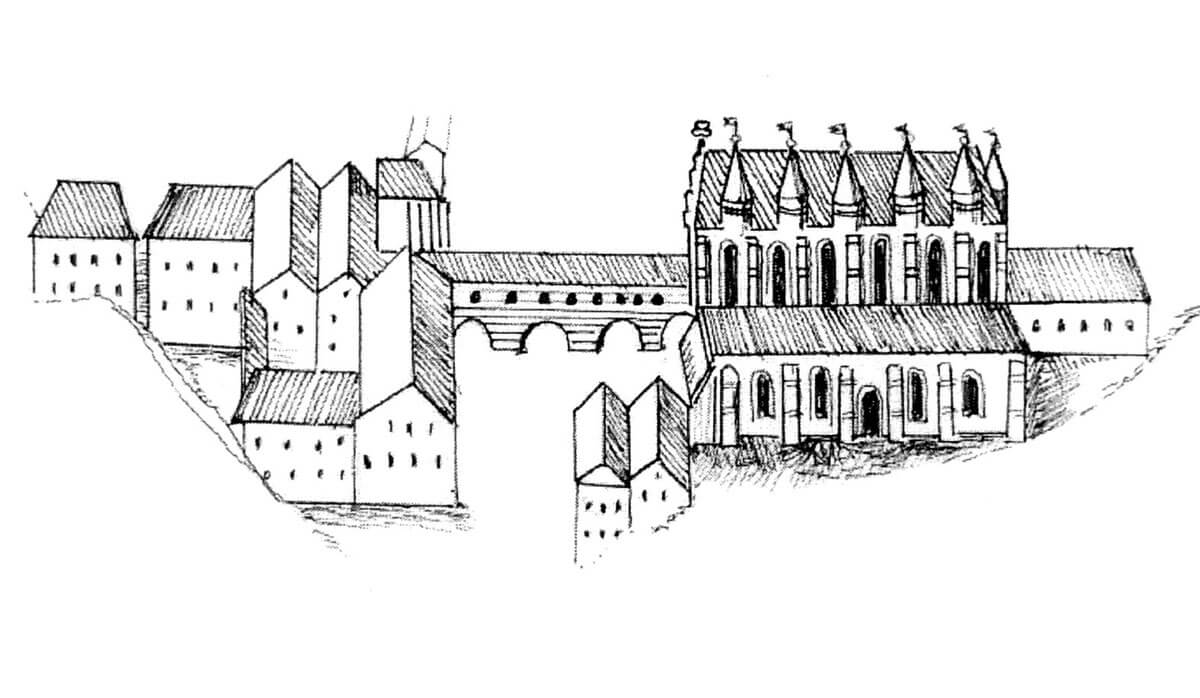

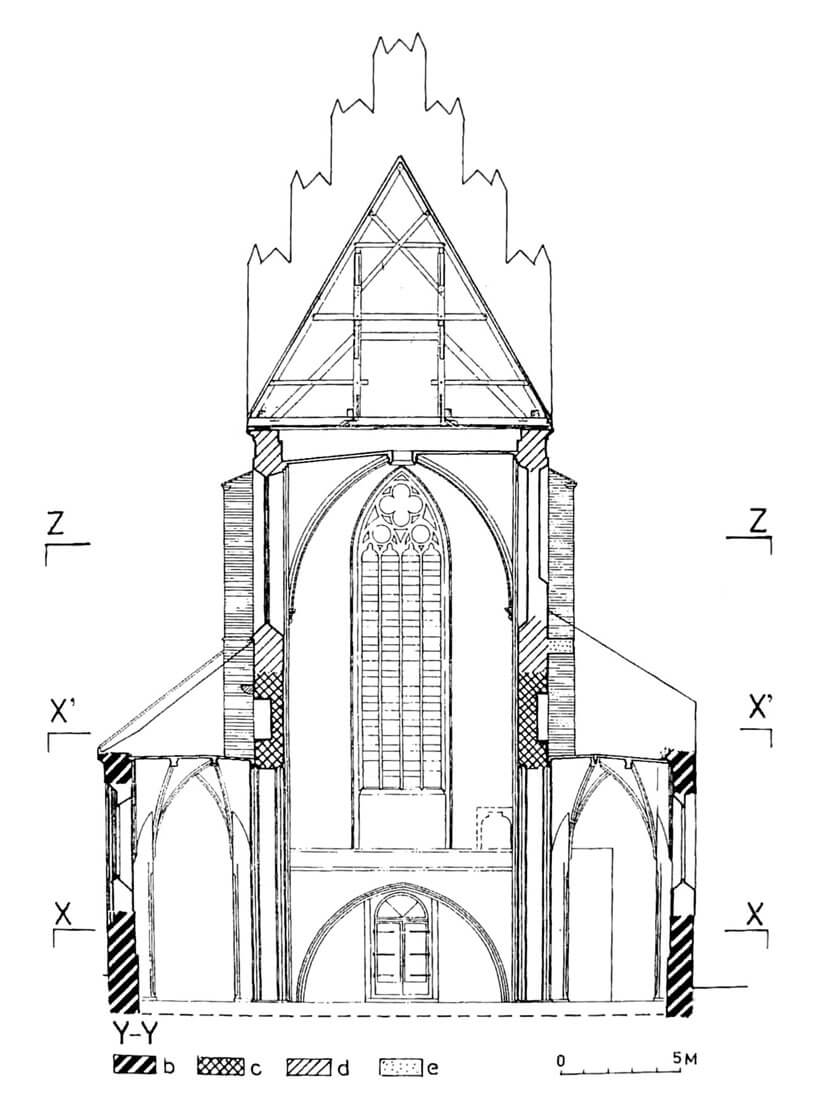

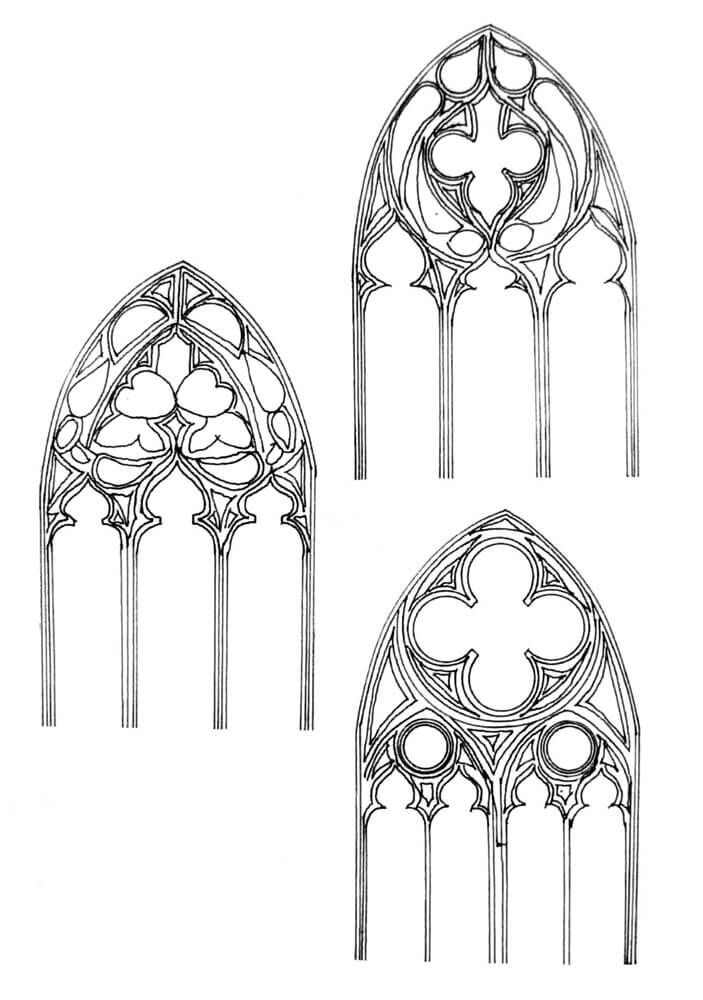

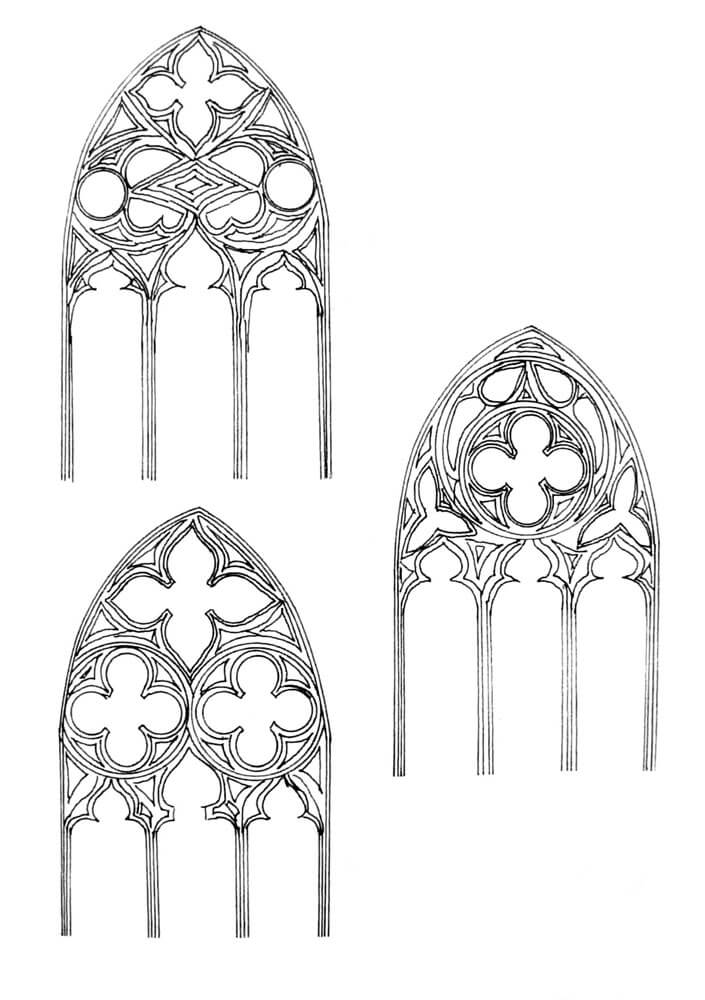

The outer facades of the walls of the aisles were aligned with the buttress contour, resulting in smooth surfaces (although the buttresses were still clearly marked in the drawings from the 16th century). Also smooth western façade was decorated with a slender ogival window filled with tracery and a ceramic gable with pinnacles and blendes. Below, an ogival entrance portal led, originally devoid of porch. Only the facades of the walls of the central nave and the presbytery were divided with buttresses, and the whole was covered with a gable roof over the central nave and mono-pitched over the aisles. From at least the end of the 15th century, the central nave was crowned with five or six turrets, set just above the dripstone cornice. This unusual element could be related to the close location of the church near the city fortifications and its possible auxiliary defensive functions.

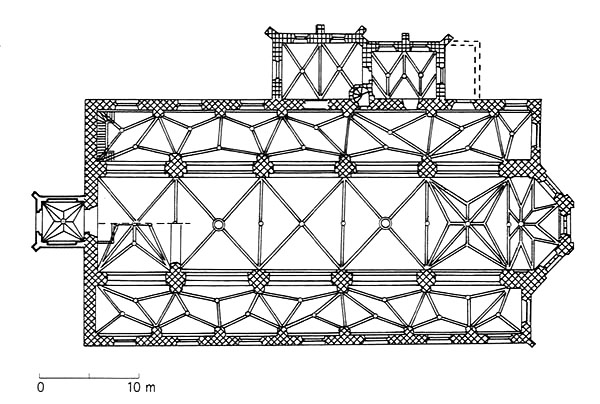

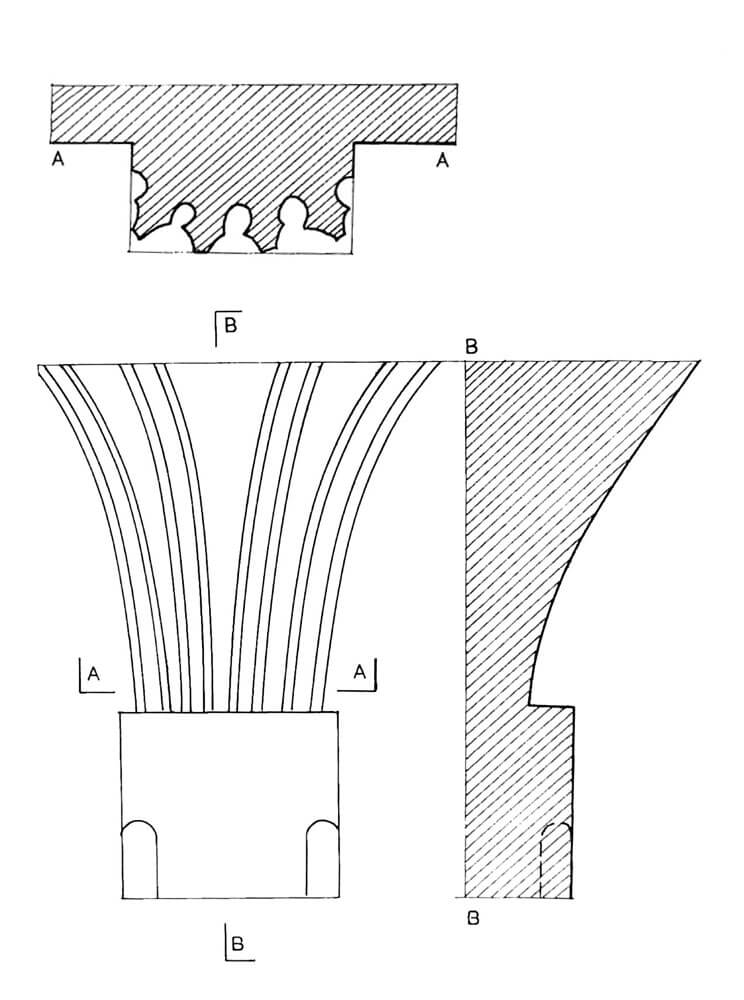

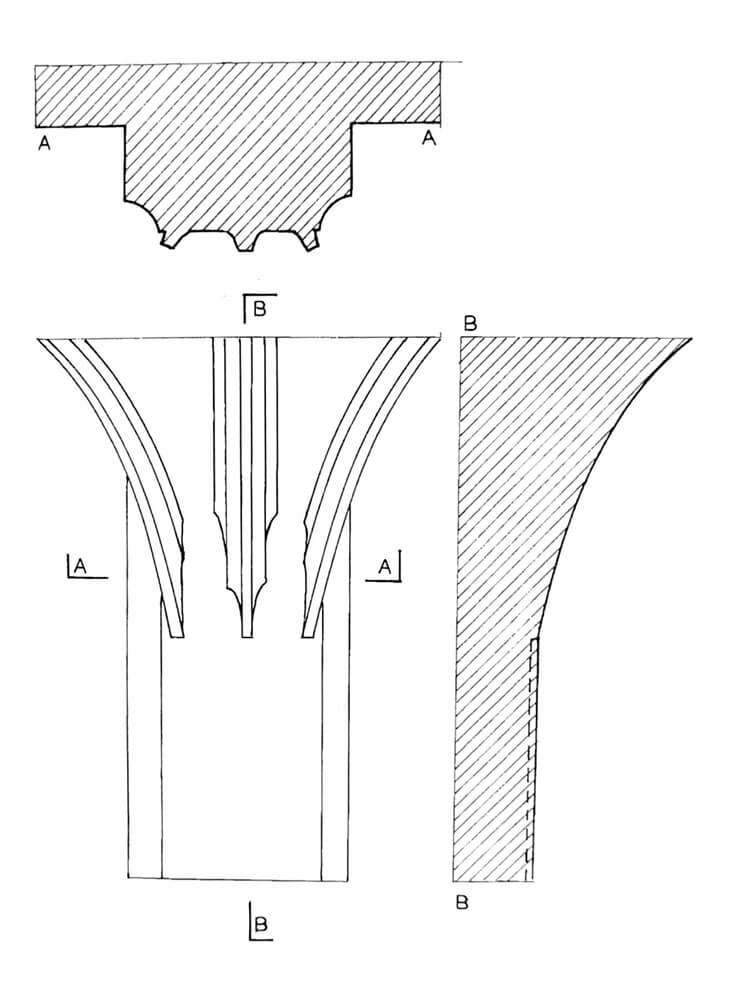

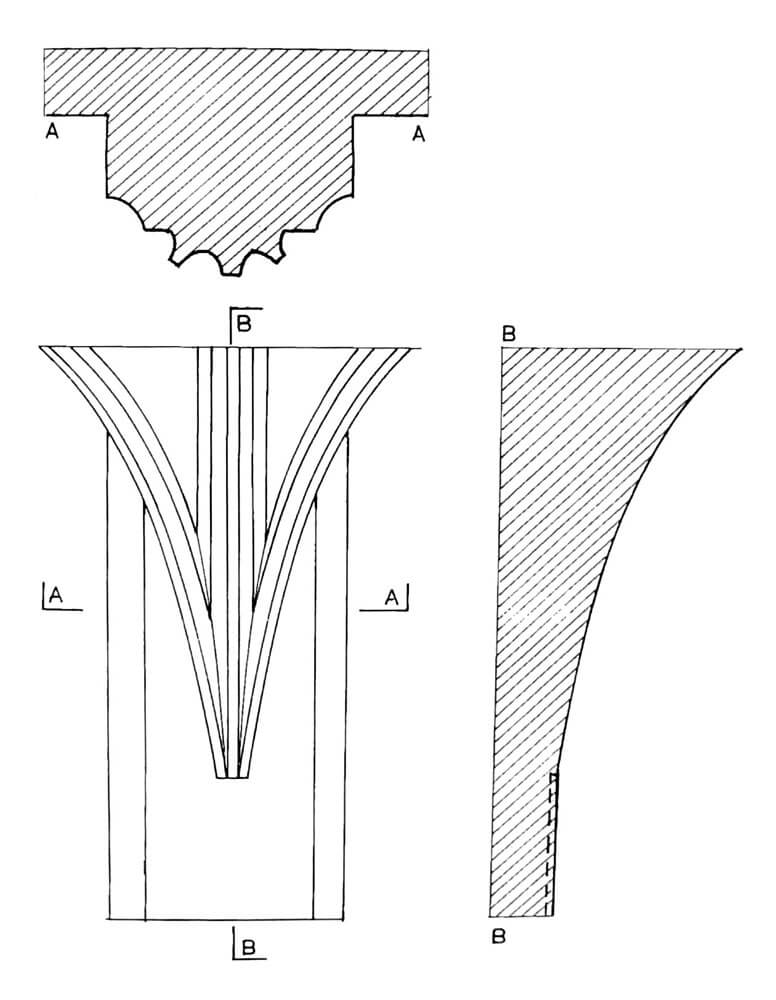

The interior of the church is divided into five rectangular bays of the central nave and five irregular bays in the aisles. The main nave was covered in the first bay from the east with a net vault, in the second bay with a stellar vault, and in the remaining bays a cross vault was used. The aisles and sacristy were crowned with three-supporting vaults, while the annex at the sacristy with a cross vault.

Originally, a covered porch ran from the church to the order’s commandry on the west side. It had four ogival arcades carrying a porch covered with a gable roof, illuminated from both sides by rows of small windows. The porch connected with the west facade of the church, where it ensured access to the gallery, inserted in the ground floor of the west bay of the central nave.

Current state

Rebuilt from the war damages and subjected to extensive renovation in recent years, the church is today one of the most valuable, though less known, historic buildings of Wrocław. From among the old furnishings, a stone, Gothic sacramentary from the 15th century and a tombstone of two Knights Hospitallers have been preserved on the north wall of the aisle. A valuable element of architectural detail is the gothic western gable and a set of carved vaulted bosses. The original window tracery have survived in the eastern closure of the central nave.

bibliography:

Antkowiak Z., Kościoły Wrocławia, Wrocław 1991.

Łużyniecka E., Gotyckie świątynie Wrocławia. Kościół Bożego Ciała, kościół Świętych Wacława, Stanisława i Doroty, Wrocław 1999.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.