History

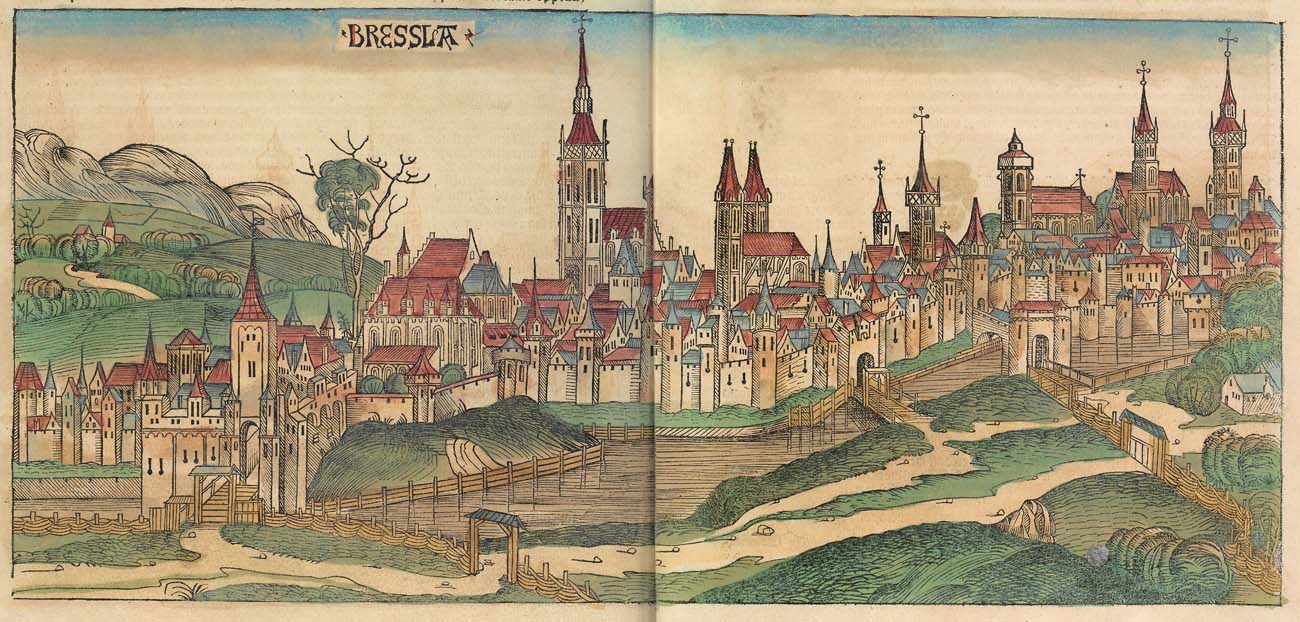

Wrocław was founded at the crossroads of important trade routes leading from the south to the Baltic Sea and from Ruthenia to the west. In the early Middle Ages it was one of the most important settlements of the Silesian tribe. From the end of the 9th century until the mid-10th century, together with the whole of Silesia, it belonged to the Bohemian state, and from around 990 it became part of the Piasts state. The main element of Wrocław at that time was a wooden and earth stronghold on Ostrów Tumski, the seat of the feudal ruler and his retinue. Next to it, in the fortified outer bailey, lived craftsmen and merchants. In 1000, Wrocław was chosen as the seat of the bishopric, and from 1138 it was the capital of a separate district. It began to play an increasingly important role, so the area of the original outer bailey on Ostrów Tumski, too small for the rapidly growing population and new buildings, was expanded to include areas outside the island. In addition to the Benedictine abbey in Ołbin and the monastery of the Canons Regular on Piasek Island, a number of settlement clusters developed on the left bank of the Oder, around which the first market square was planned and streets were laid out in the times of Prince Henry the Bearded.

The intensive development of Wrocław was temporarily interrupted by the Tatar invasion in 1241. The destruction caused by the Mongols made the townspeople aware of the need to erect brick defensive walls around the city, which would replace the older wooden and earth fortifications. The construction of brick walls began after the mid-13th century or at the earliest in the 1240s. Work on them was probably already underway during the city’s re-foundation in 1261. The foundation document issued by Prince Henry III and Prince Władysław recorded butchers stalls and gardens located “ante civitatem infra fossata prime locationis”. Two years later, the fortifications of the then-founded New Town of Wrocław were recorded. In 1272, Prince Henry IV Probus confirmed and extended the privileges for the city “intra muros”, and in 1274 he financially burdened the residents “intra muros civitatis Wrat(islauie)” and “ad muros intra fossata”. These references would indicate that construction work on the most important sections of the wall was completed around the beginning of the 70s of the 13th century, although the city wall on the river side was still being built until the end of the century. In 1291, the ditch in front of the walls was replaced with a watered moat, filled from the Oława River on the orders of Henry V the Fat, who hastily strengthened the defensive perimeter in the face of the conflict over the succession to Henry IV (this moat was later called the Black Oława).

The city grew rapidly and already in the 14th century the buildings that were built outside the walls were so significant and extensive that it was decided to build a new circuit of walls preceded by a moat from the south and west. Work on the new section lasted from the end of the 13th century to about the middle of the 14th century. The most recent note related to new fortifications was recorded in 1299, when the construction of the second Oława Gate and adjacent sections of the wall was mentioned. Then, since 1303, the city account book recorded expenditures on construction works. Their amount varied from year to year. A very large sum of 159 fines for walls and gates was recorded in 1305, but already in 1306 the expenditure amounted to only 8 fines, while in the following year nothing was spent due to the war operations conducted at that time. In 1308, the expenditure increased to 52 fines, and was then recorded with breaks until 1348, when the works related to the construction of the defensive wall and moat were completed, with the greatest intensity of construction works on the wall and towers recorded from 1337 to 1343. In 1351, when the church of St. Stanislaus, Wenceslas and Dorothy was founded, it was described as “inter duos muros”.

The area of the New Town, formally incorporated into Wrocław in 1327, received brick fortifications on the eastern side only in the 15th or early 16th century. The older inner wall from the 13th century had already lost its military function than. Crossed by many gates leading to bridges over the Black Oława, it was gradually absorbed by residential buildings. The earliest, at the beginning of the 14th century, this process began on the western side, where settlements of small houses of fishermen, white-skinned men, wheelwrights and potters were built on municipal land. In 1331, a wall rent was recorded, paid by the owners of plots adjacent to the old defensive wall, who built up the area of the former street under the wall. The area along the old section of the wall, divided by the city council into small plots, became more accessible to lower-class citizens than large plots located in the suburbs. Initially, they erected temporary half-timbered buildings next to the decaying fortifications, and from the second half of the 14th century brick houses, which in the 15th and 16th centuries led to the almost complete removal of the inner circuit of fortifications, with the exception of the Black Oława moat transformed into a canal.

Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the fortifications of Wrocław were constantly expanded and improved, as warfare technology changed. With the spread of gunpowder and under the influence of experiences from the Hussite Wars, in the 1470s, construction of a second, outer ring of fortifications with low towers began. In addition, the defensiveness of the gates was reinforced with foregates and positions for firearms were prepared. In 1427, the Nicholaus Gate was to be rebuilt, and modernized again in 1479. Work on the second line of fortifications continued until the beginning of the 16th century, when it was accelerated due to fear of the Turks. In 1522-1525 the Świdnicka Gate was rebuilt, in 1528 the construction of the bastion at the Brick Gate began, from 1530 work was underway on the wall behind the All Saints Hospital and between the Świdnicka and Nicholaus Gates. In 1531, the extension of the city moat from the Świdnicka Gate to Nicholaus Gate began. It was recorded at the time that every resident of Wrocław, regardless of wealth, had to give 5 groshen for this undertaking. The last major modernisation works on the external wall were carried out before 1562, when it had already become only a retaining wall for the high rampart that had been built at that time.

In the 17th century, a bastion system was created in front of the late medieval fortifications. This necessity, completely changing the appearance of the city’s foreground, resulted from the changes in fighting methods that had occurred since the end of the Middle Ages. The development of firearms and siege techniques, and above all the use of increasingly powerful artillery, meant that the old brick city walls lost their defensive value, while the city with its constantly growing population lacked space for development. Therefore, after the capture of Wrocław by Napoleon’s troops, starting in 1807, a long-term process of demolishing the medieval defensive walls began. In 1869, the old inner moat (Black Oława) was filled in, whose contamination caused numerous cholera epidemics. However, the outer moat was left, as it became part of the park planted on the site of the 14th-16th century walls. The streets and alleys running along the 13th century city walls were demolished during and after World War II, and the final removal of their relics was brought about by the construction of the city bypass road in the 1970s.

Architecture

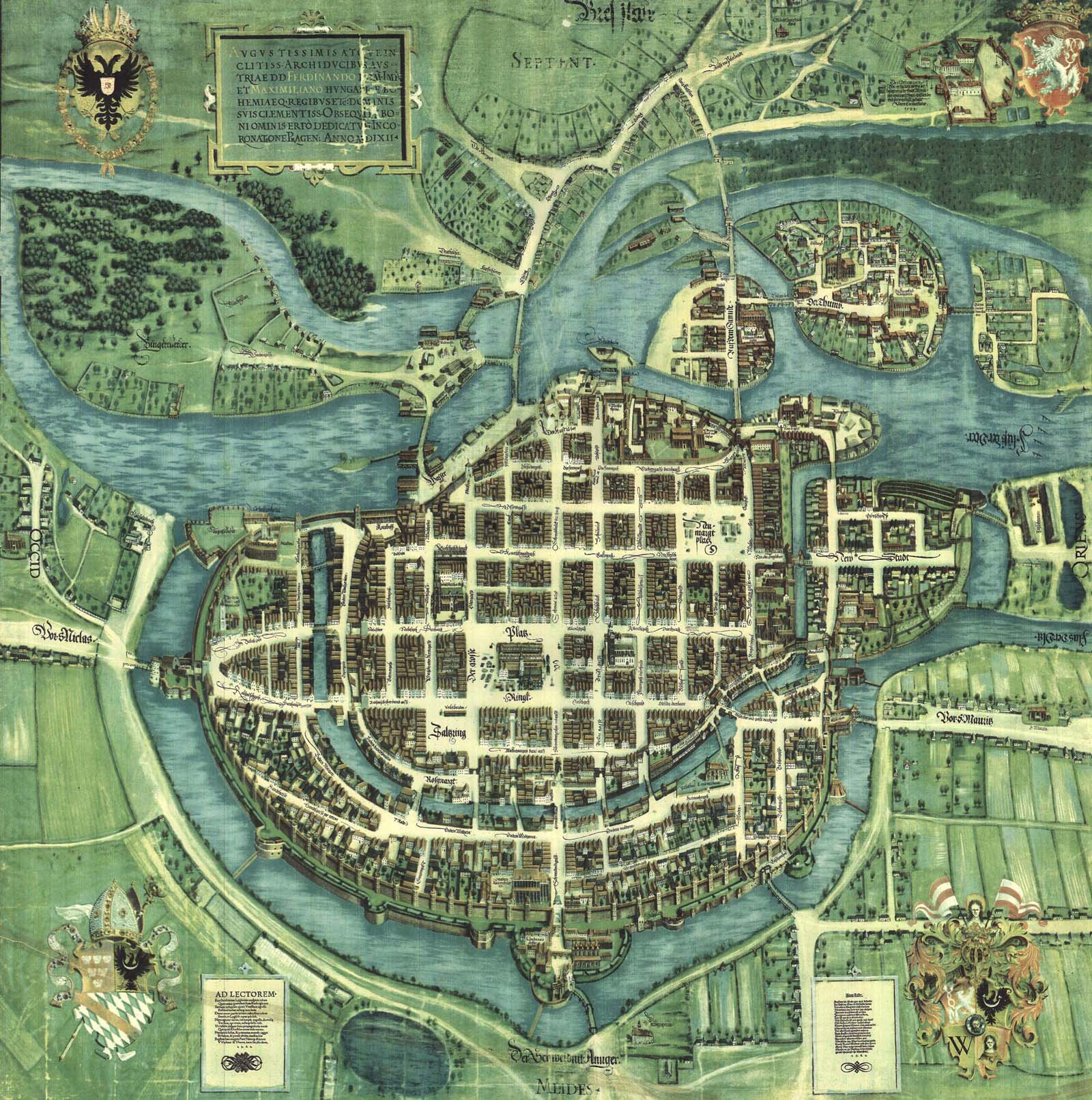

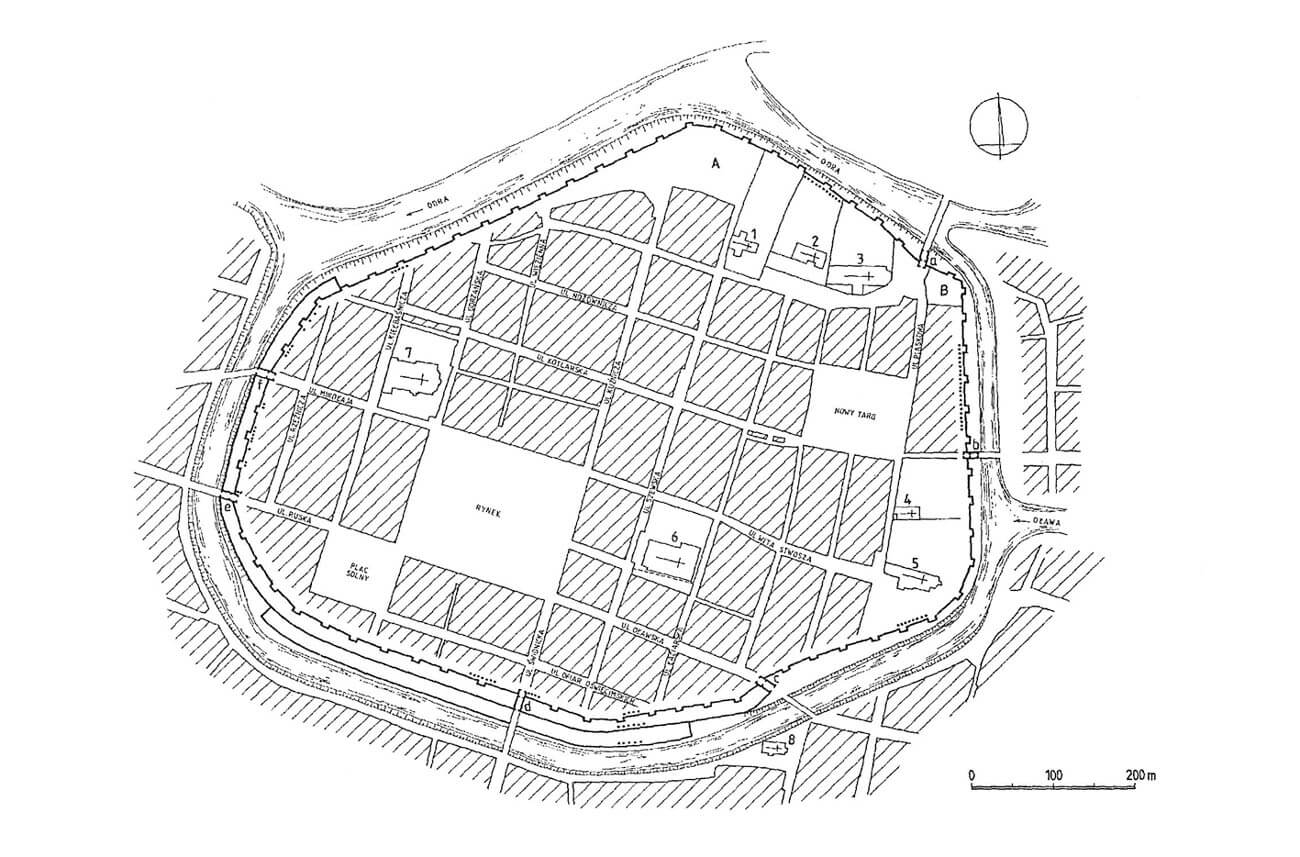

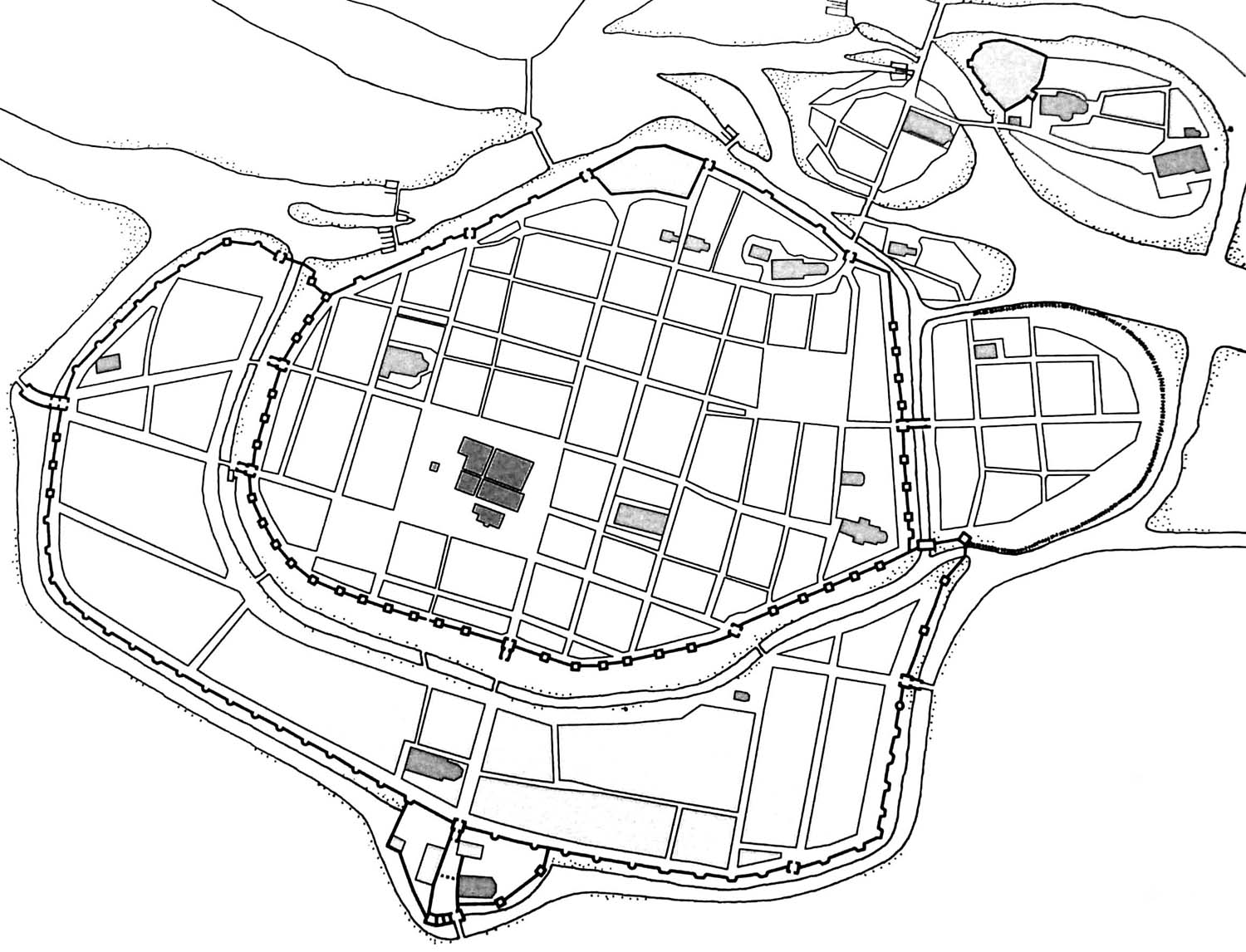

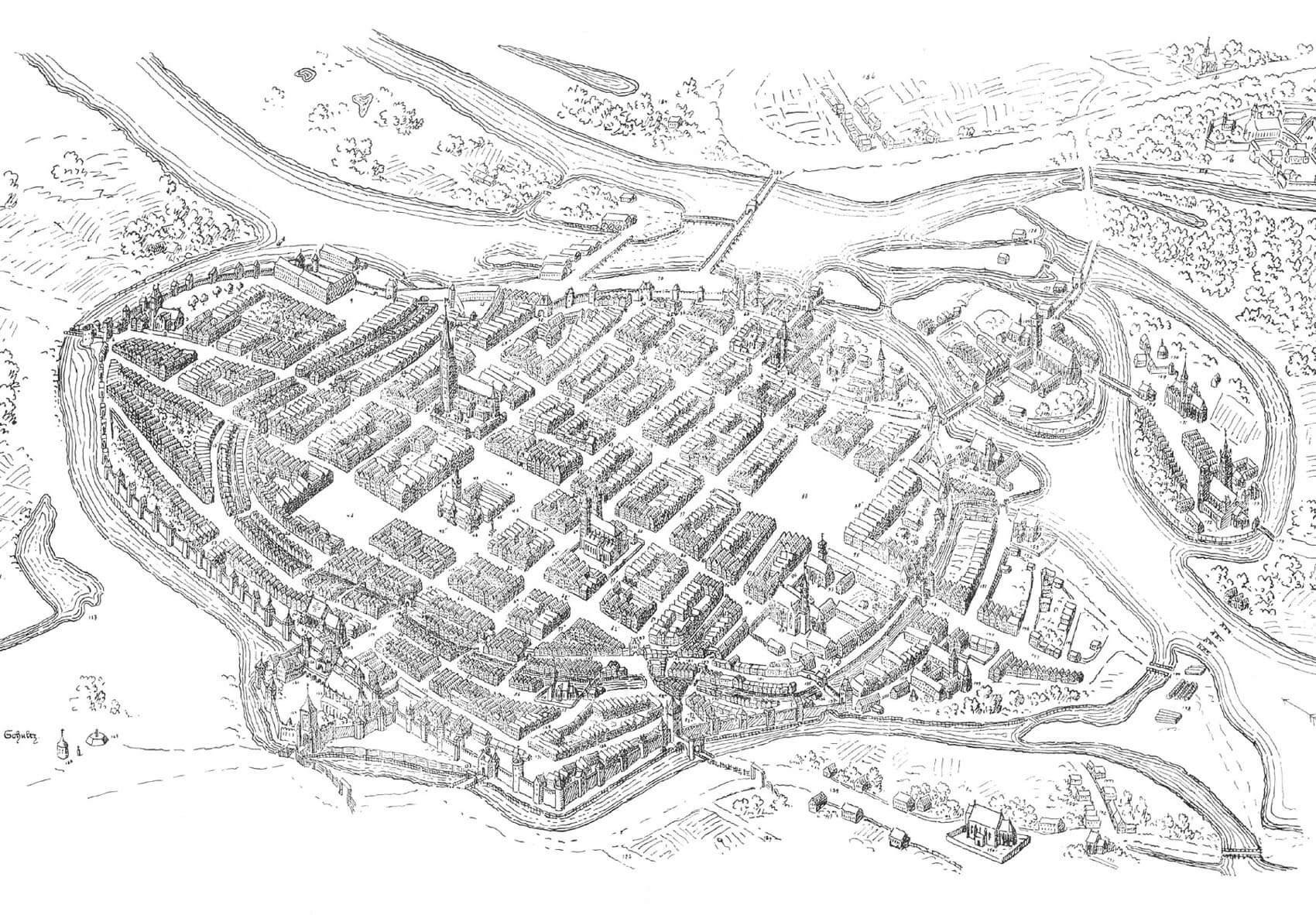

Wrocław was founded on the southern bank of the wide Odra riverbed and its numerous branches bypassing the islands, and on the south-western side of the smaller Oława riverbed. It was created on a flat terrace, raised about 5-7 meters above the river’s water level. In the mid-13th century, the chartered city acquired an irregular, oval-like shape plan, slightly elongated on the east-west axis, occupying about 40 ha of land. The city fortifications, about 2,000 meters long, covered the most densely populated area, although their course did not coincide with the city boundary planned at the time, as evidenced by the intersection of plots on the inner side of the defensive wall. The city space was covered by a regular network of streets, connected to the market square and two other squares. The main streets ran from their corners and in most cases were directed towards the city gates. An underwall street ran along the walls, facilitating communication for defenders in the event of a threat.

From the end of the 13th century, the Oława River separated the main part of Wrocław from the New Town in the north-east. In addition, in the north, a branch of the Oder River separated the area of the monastery of regular canons located on an island and the island occupied by Tum Castle, located a little further away from the city. In the north-west, on the other hand, a short, irrigated branch of the moat probably separated the area of the city and the castle on the left bank (later the city arsenal). The third castle in Wrocław, the so-called Imperial Castle, built at the beginning of the 14th century, was already located inside the city’s defensive perimeter, in the northern part of Wrocław. In the south and south-west, outside the oldest perimeter of the defensive wall, there remained quite densely populated suburbs, which led to the rapid expansion of the city’s fortifications.

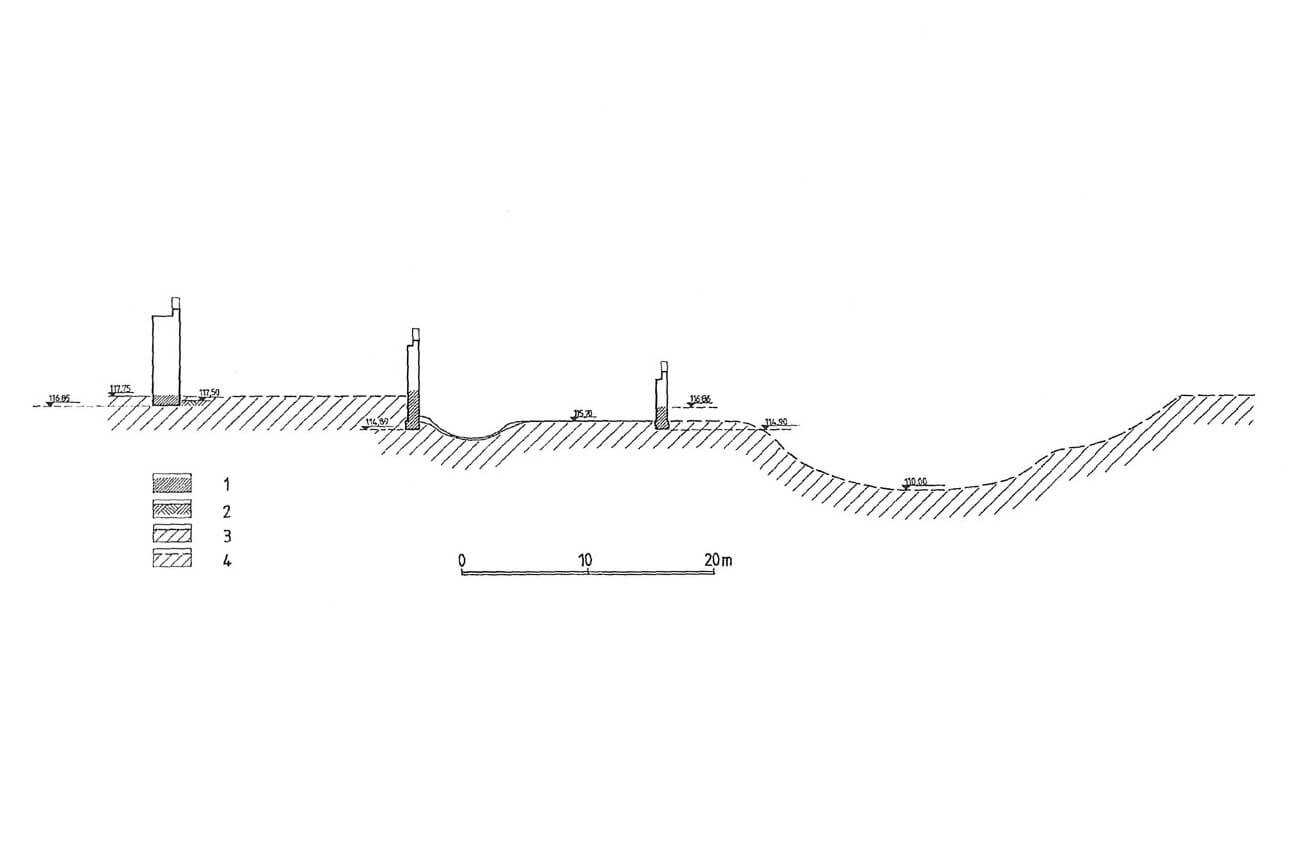

The defensive wall of Wrocław from the second half of the 13th century was built of bricks using the opus emplectum technique, with a face in a monk bond and a core filled with rubble filled with lime mortar. Its foundations were made of boulders sealed with humus and brick rubble. It were shallow, which was compensated by covering it from the outside with a layer of sand. The wall was about 6-7 meters high (including the parapet 8-9 meters), about 2-2.3 meters thick at the ground level and topped with a battlement, which protected a wall-walk about 1.6-1.7 meters wide. The merlons were less than a meter high, about 0.6 meters thick, from 2.2 to 2.9 meters long and were separated by about 0.9-1.2 meter gaps for firing (the merlons themselves probably did not have arrowslits). The wallwalk placed behind the parapet did not require widening with a wooden porch, due to the considerable thickness of the wall crown. At a distance of about 16-19 meters in front of the wall line ran a ditch, created along the entire perimeter, except for the northern section, which was protected by the Oder. The moat was initially 3.2 meters deep and its width varied from 12 to 14 meters. The earth extracted from it was probably used to create a rampart.

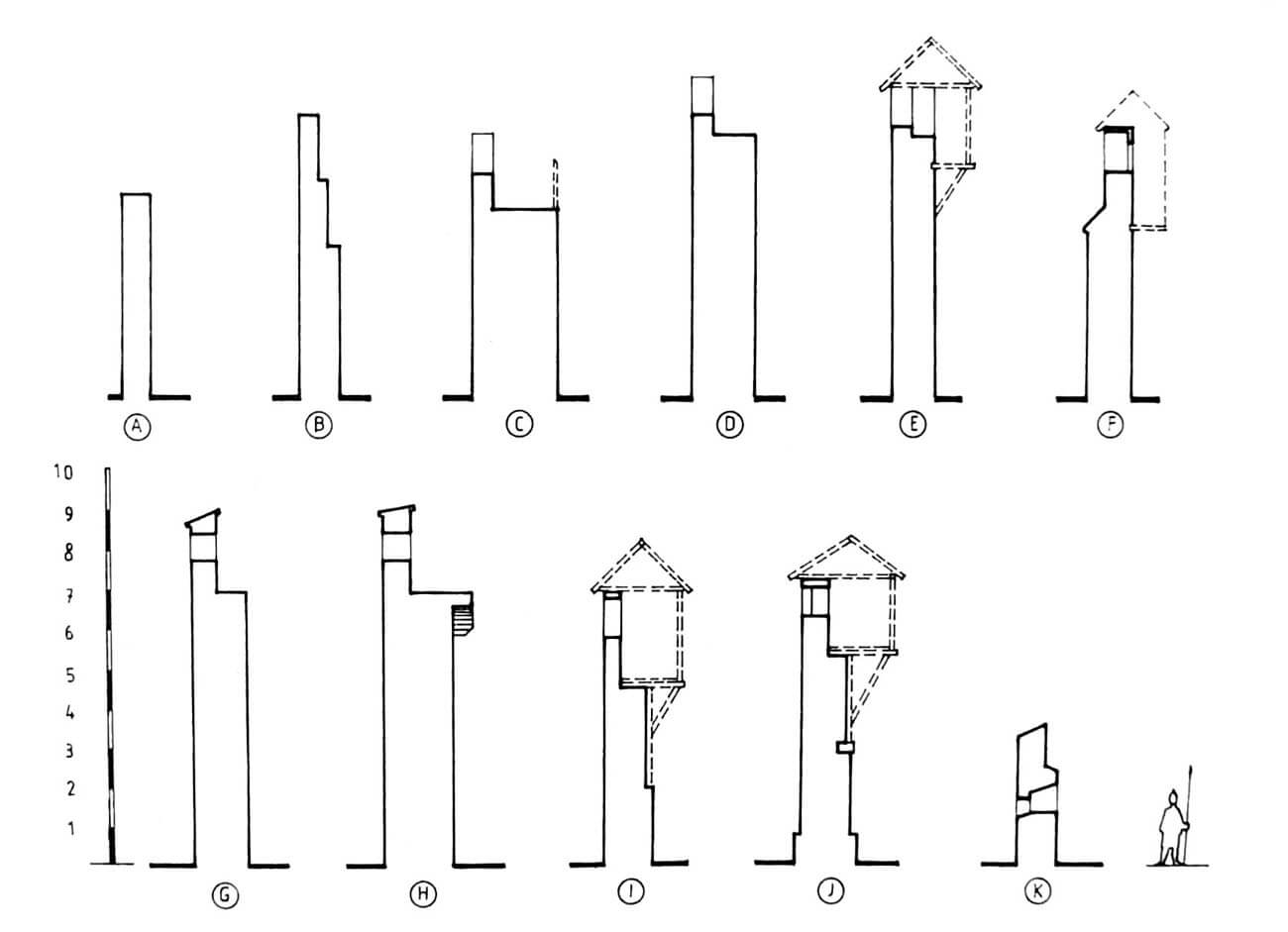

The wall from the second half of the 13th century was reinforced by about 62 rectangular half-towers, placed at regular distances of about 28-32 meters, i.e. within a range allowing for an effective shot from a bow or crossbow. The towers were used on most of the perimeter, but on the safest section in the northern part of the city, on unstable earth on the banks of the Odra and Oława rivers, they were placed at greater intervals. It had a quadrangular plan and projected in front of the defensive walls on both sides. All the towers were probably originally similar in height to the curtains of the wall, opened from the city side and topped with a crenelation. The front part of a typical 13th-century Wrocław tower was about 7.8-8 meters long, while the side walls, protruding in front of the curtains, were from 2.1 to 4 meters long.

The southern section of the fortifications, which was most at risk of attack, was additionally reinforced with two lines of defensive walls, creating a double zwinger with terraces widths from 16 to 19 meters, with a level difference of 2 meters between them. The zwinger walls were about 1 meter thick above the ground. The wall of the inner zwinger was probably higher, reaching about 4-5 meters together with the parapet, and additionally there was a ditch underneath it, which was a remnant of the original moat from before the expansion of the fortifications. The wall of the outer zwinger could have been about 3 meters high. Both were not reinforced with a system of towers, but could have been topped with a wall-walk and a parapet. The strip of 13th-century outer walls, like the sections of the wall without the zwinger, was preceded by a wide moat filled with the waters of the Oder and Oława rivers. Its maximum width was about 46 meters, while the depth reached 6.5 meters in the main axis and 5 meters in the coastal part reinforced with wood. After the completion of the fortifications at the end of the 13th century, the most extensive southern section of Wrocław’s fortifications was as much as 75 meters across. Moreover, when in 1261 the inhabitants of the southern suburbs received city rights, their buildings were temporarily secured with a ditch and an earth rampart.

In the first half of the 14th century, the area of the original chartered city was enlarged from the west and south by about 25 ha, and also extended to the east, where the former New Town of about 10 ha was incorporated into Wrocław. At that time, the old fortifications lost their importance and began to be gradually transformed. The earliest, probably before the completion of the new fortifications, was the street under the wall. The defensive wall served as a support for the light economic buildings, and over time it was incorporated into the residential brick buildings. Its considerable thickness began to be a disadvantage at that time, so it was gradually demolished, thanks to which it was possible to build thinner walls of residential houses and gain a few square meters of additional space. The half-towers were easy to adapt for residential and utility purposes, which only needed to be closed with a wall on the city side. Some of them were also raised, while in some, after deepening, basement rooms were created. The old city gates survived the 14th-century reconstruction without any major changes, preserved despite losing their defensive function, as a symbolic and prestigious element. In order to facilitate communication between the older and newer parts of the city, simple wicket gates were built on the extension of most of the streets leading from the Old Town. It had no defensive features, but if necessary, could be easily barricaded. The old moat was also left, which was a source of water for the residents, thanks to its connection with the waters of the river. Access to it was possible thanks to numerous ramps and platforms, placed mainly at the gates. As a result of losing its military significance, the inner moat was deepened and narrowed to about 14-16 meters. The city council made efforts to transform it into an economic and communication channel, which is why initially the banks were protected from erosion with fascine and wooden structures, and in the 16th century a brick wall was built, additionally secured with wooden structures. The narrowing of the moat and its silting up caused a problem with the water level in White Oława in the eastern part of the city. The solution was to change the course of the water in the moat in 1460.

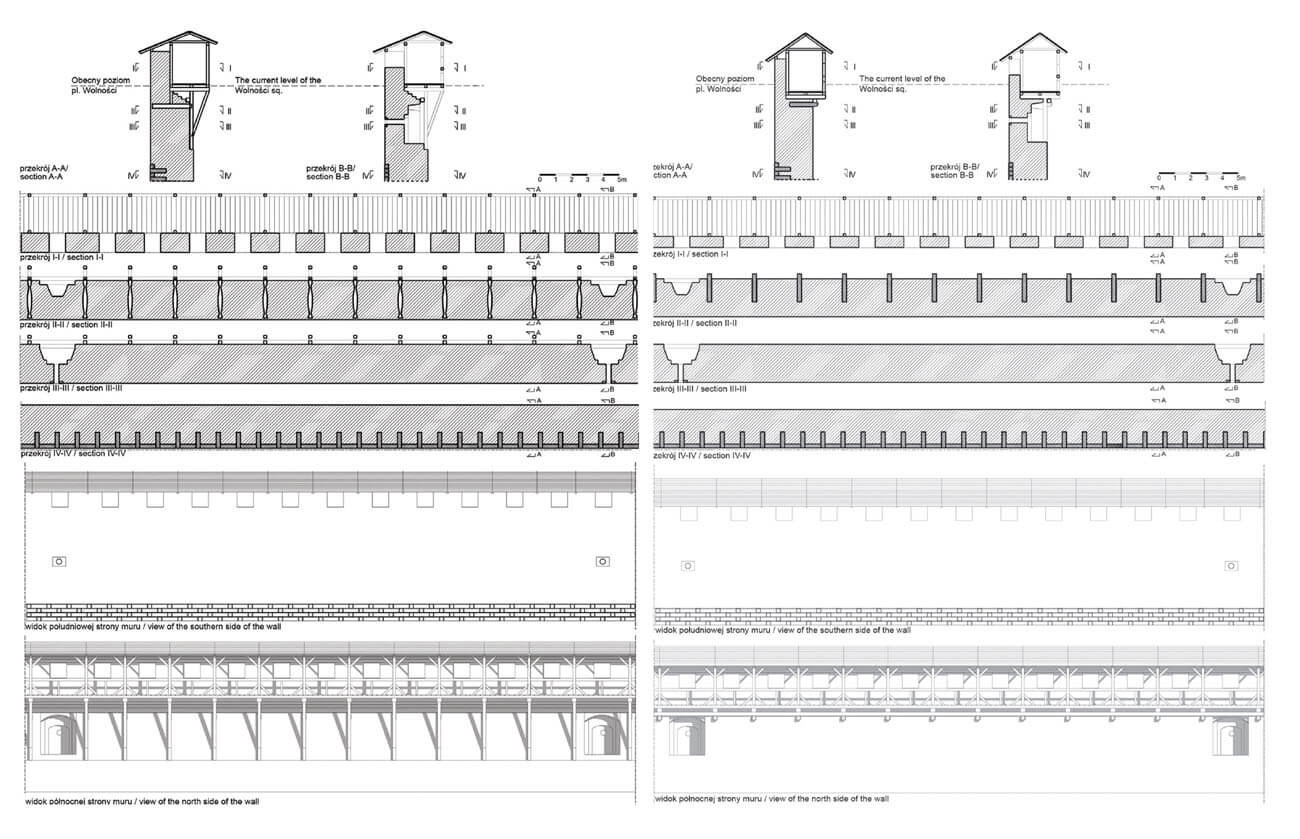

The defensive wall from the first half of the 14th century, built in the south-eastern, southern and western parts of the city, reached about 2,500 meters in length. It probably reached a total height of about 7 meters, of which about 2 meters was the parapet. The thickness of the wall at the ground level varied greatly, ranging from 1.1 to 1.6 meters, but most often around 1.2 meters. It was built on the ridge of a sand-fascine rampart, which surrounded the area of the former southern and western suburbs. The new perimeter consisted of walls almost half as thin, which is why its wall-walk had to be created on a wooden, covered porch, placed on an offset and supported by diagonal beams (in some sections the porch could be supported by consoles). The dimensions of the battlements could have been similar to those in the 13th-century sections (merlon width from 2 to 2.5 metres, height 1.1-1.2 metres, gaps between merlons from 0.9 to 1.2 metres, total height of the parapet 1.9-2.1 metres, thickness around 0.7 metres). In some sections, the battlements were to have loop holes, pierced in every other merlon.

The defensive perimeter of Wrocław from the 14th century, was reinforced with around 50 half-towers, this time not only quadrangular, but also semicircular and polygonal (the latter of which could have been the result of later transformations). All of them were initially opened from the city side and protruded in front of its face. Originally, it were probably similar in height to the neighbouring curtains, but some of the towers were raised by about 3 metres in the late Middle Ages, built on the city side and covered with hip roofs. The 14th-century towers were usually set regularly, at intervals of about 30-36 metres, but greater differences could have occurred in places where the perimeter of the fortifications bend. For example, in the south-eastern part of the perimeter, the distance between two towers was only 27.5 metres, and in the south-west as much as 41.7 metres. The increased distances between the towers in relation to the 13th-century fortifications could have resulted from the greater range and accuracy of weapons, as well as the appearance of hoarding or machicolations, eliminating blind fields of fire.

The sizes of the towers of the southern and western parts of the fortifications differed significantly, which resulted from their different shapes, the long process of building the fortifications, places with varying degrees of importance, and probably also from the transformations, repairs and modernisations carried out in the 15th and 16th centuries. The quadrangular towers usually had frontal walls of 6.3 to 7.7 metres, although the largest known in the south-eastern part of the city had sides of 12.8 metres. The thickness of the towers’ walls at ground level was about 1.1-1.6 metres. It protruded in front of the neighbouring curtains by a distance of 2.8 to 3.9 metres, while the large south-eastern tower protruded as much as 5.6 metres. The semicircular towers had an external diameter of about 6.3 – 7.2 metres, and an internal diameter of 3.4 to 4.5 metres. It also protruded in front of the neighbouring curtains by a distance of about 2.3 – 3.9 metres. The defense in the towers was based on loop-holes, probably slits of a varied number and arrangement. On the highest storey, fire could be provided from between the battlements. The number of storeys of the towers could be variable, from two to even four. Vertical communication was originally provided by ladders or external wooden stairs, also attached to the curtains of the defensive wall, from where one could get to the towers. In time, brick staircases could also be built inside the towers.

In front of the defensive wall, the outer defence zone in the 14th century was again a watered moat and still the Oder River from the north. When the outer line of fortifications was marked out from the west and south, an outer moat was also dug from two sides of the city, about three hundred meters away from Black Oława and connected with a short western and eastern section of the old moat and the Oława River. The eastern connection took place in the corner, where the Old Town met the New Town. The old ditch, which had protected the Wrocław suburbs in the 13th century, was used to build new sections of the moat. It was deepened to about 3 meters, widened to about 20-30 meters and, above all, filled with the waters of the Oder River. Both banks were boarded with wooden poles and horizontal planks. In the following years, these wooden structures were successively replaced and reinforced with increasingly massive ones.

In the 70s of the 15th century, the construction of external fortifications began. In front of the main wall from the 14th century, an earth rampart and a low but thick wall about 2.4-2.5 meters wide were built, made of bricks in the opus emplectum technique, in the lower part, from the side of the moat, faced with stones. Above the stone strip, there were recesses, about 1.3 meters away, presumably for loop holes, with splayed jambs, probably crowned with segmental arches, with stone framed openings from the side of the moat, alternately round and partially rounded. The recesses were about 2.5 meters high. At their upper edge, there were sandstone, square corbels ending in a quarter-circle at the bottom, which probably served as a support for the timber porch or hoarding. The wall was crowned with a brick battlement with a thickness of 2.5-3 bricks, but the younger (western) sections were thicker. A characteristic feature of the later created curtains were also timber transverse braces, ended in the form of double dovetails. They were probably a structural element of the original porch, in the western part of the fortifications founded on steps rising towards the breastwork. After some time, the loop holes in the wall were bricked up, which could have been caused by the rising level of the moat, or they could have been ineffective due to the significant thickness of the curtains. The outer wall from the 15th / 16th century was reinforced with ten semicircular bastions.

In the 13th century, the city was initially entered by five gates: Świdnicka from the south, Nicholaus and Rus from the west, Oławska from the east and Sand from the north (the latter probably being an ordinary tower at first, raised and equipped with a gate passage at the beginning of the 14th century). Before the end of the 13th century, the Brick Gate was built, connecting the main part of Wrocław with the New Town. The 13th century gates were mostly in the form of towers on a square plan, with a passage on the ground floor axis. It were probably closed with drawbridges and topped with a hip roof covered with shingles. In front of the 13th century gate towers there were simple foregates in the form of necks, composed of long side walls and short front walls with entrance portals. After the 14th century expansion, the new gates: Świdnicka, Nicholaus and Oławska took over the names of the old 13th century entrances, because it were located on the extension of the same streets. The auxiliary Bag Gate was also built in the south-eastern corner of the city, as well as the modest Oder Gate in the north. The passageway located within the defensive perimeter of Wrocław was the Heretics Gate, connecting the New Town with the area of the left-bank part of the city, which was enlarged in the 14th century. From the 1420s, the defensive capabilities of the gates were strengthened, by expanding the foregates protruding into the foregrounds and preparing positions for firearms.

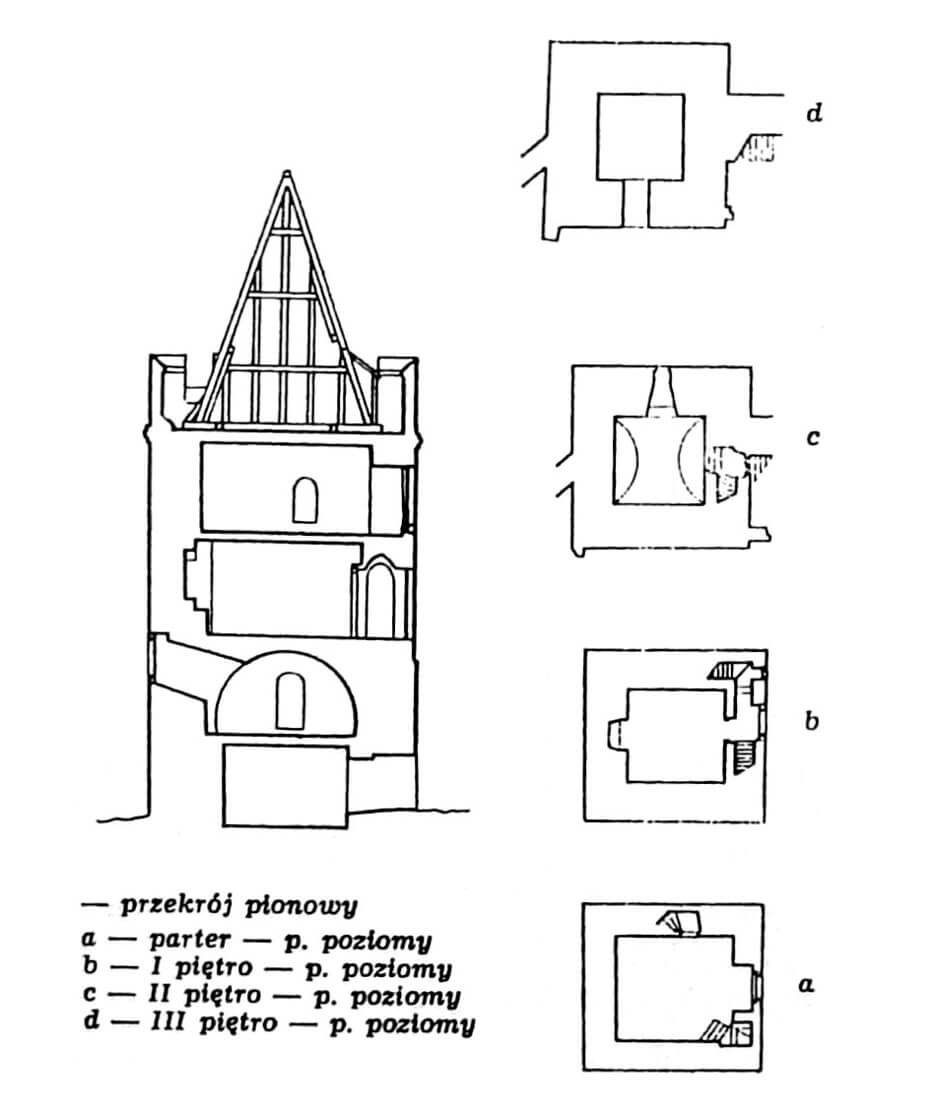

The 14th-century Oławska Gate consisted of a quadrangular tower measuring 8.1 x 9.2 meters, projecting on both sides in front of the adjacent curtains of the defensive wall. The thickness of its walls was 2 meters, while the width of the cobbled passage in the ground floor was 3.2 meters. Above it, there were probably two storeys lit by small openings. The highest storey could have been of wooden or half-timbered construction, with four turrets in the corners framing a high hip roof. Probably before the mid-15th century, a foregate was built in front of the tower, 10.4 meters wide and about 21 meters long. It was wider than the gate tower, so it overlapped it by about 0.6 meters from the north and 1 meter from the south. Under the foregate there was a water culvert of the moat, covered with a barrel vault, the arcades of which were about 0.8 meters high and stretched over the water to a width of about 9 meters. Massive arches carried the weight of at least partially roofed walls with loop holes. The front part of the foregate consisted of two semicircular towers or bastions, connected with each other above the central passage. Both the central part and both towers were topped with a battlemented parapet, possibly also equipped with machicolations. A low gable roof dominated the entire front part of the foregate.

The Bag Gate had the form of a quadrangular tower with a passage in the ground floor, above which at the level of the highest storey there could be a machicolation box. The tower was higher than the adjacent curtains and partially protruded in front of them. It could have been situated partly at an angle to the defensive wall, due to its location on the axis of the street running at an angle. Its passage could have been protected by a portcullis or wooden door. In front of the gate there was a wooden bridge, which according to Hartmann Schedel’s chronicle from the end of the 15th century was equipped with a drawbridge. However, the gate was not preceded by a foregate. Only after the construction of the outer wall of the zwinger, at the beginning of the 16th century two round towers were placed in front of the old gate tower, flanking the passage and drawbridge placed between them. In 1536, the defense of the Bag Gate was additionally reinforced with a large earth bastion.

The Świdnicka Gate within the 14th-century perimeter of the defensive walls had the form of a high tower, built on a square plan with sides about 9 meters long. The thickness of its walls was 2.2 meters, the width of the paved passage was 3.5 meters. The tower protruded on both sides and at a slight angle in front of the neighboring curtains of the defensive wall. It was covered with a hip roof above six storeys. The gate passage was initially closed by a drawbridge, which separated the tower from the bridge. As a result of the reconstruction in the first half of the 15th century, the drawbridge was removed and replaced with a portcullis and door. From then on, to the south of the tower there was a foregate, the neck of which separated from the city the area of the Hospitaller commandry in the southwest and the All Saints Hospital with the Corpus Christi Church in the southeast. The distance from the gate tower to the northern bank of the moat was 8.8 meters. A water culvert was created above the moat, covered with a barrel vault stretching for about 11 meters. The front part of the foregate was formed by a wall pierced by a wide passage for carriages and horses located in the axis, as well as a narrow side gate for pedestrians. The foregate may have been crowned with machicolations and corner turrets. The moat at the Świdnicka Gate ceased to serve a defensive function in the 15th century. In the 16th century it became a dry ditch, which was then filled with a thick layer of sand. These activities were related to the shifting of the fortifications further south, in order to encompass the area of the commandry and the Corpus Christi Church. In their line on the southern side, a new external gate was created with a drawbridge over the shifted bed of the moat. The lack of communication between the commandery and the church was the reason for the construction of an arcaded covered porch, crossing the foregate crosswise.

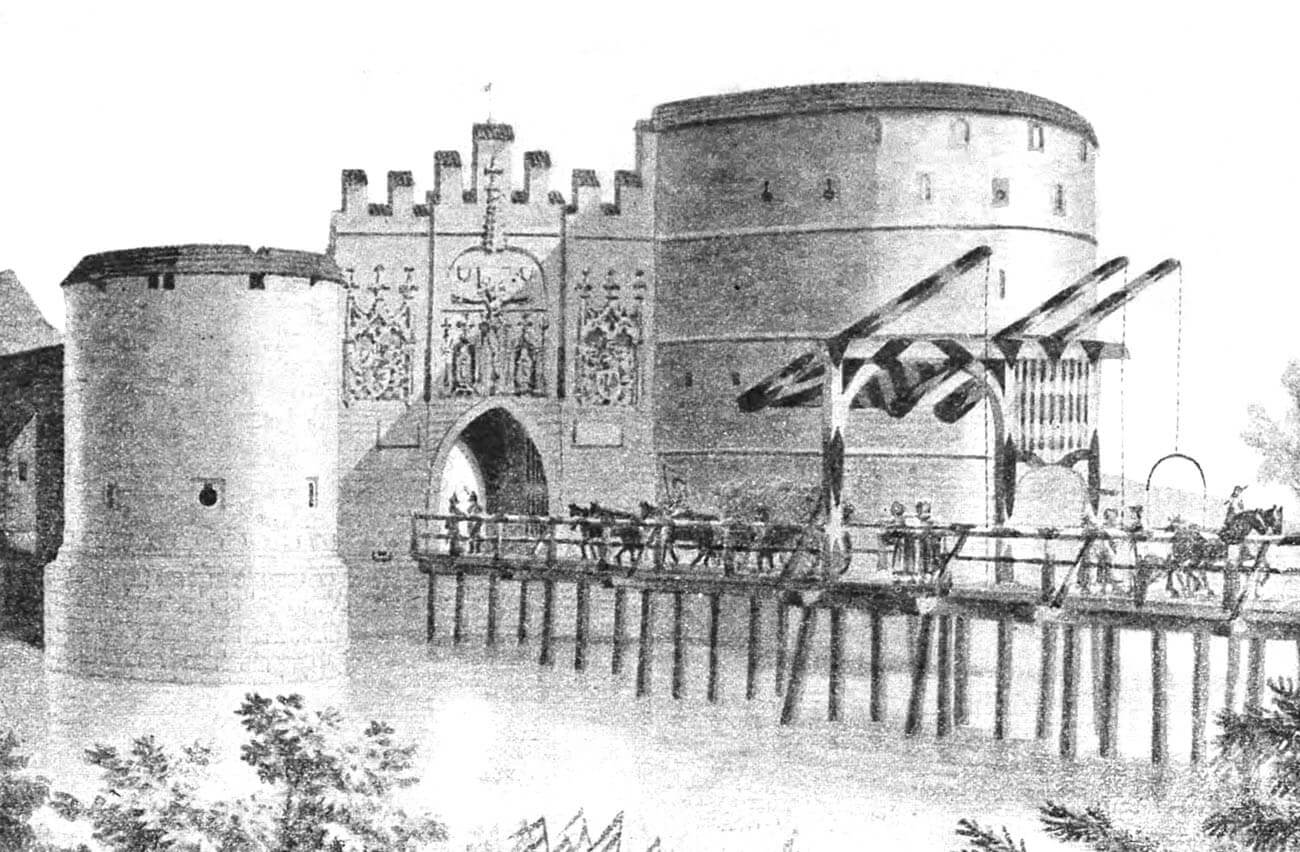

The second Nicholas Gate from the 14th century was also a quadrangular tower with a passage on the ground floor. It exceeded the crown of the neighbouring curtains by at least two storeys and was partially projected towards the moat. In the first half of the 15th century, its protection was reinforced with a simple foregate. In 1479, in fear of invasions and as a result of experiences after the Hussite Wars, the foregate of the Nicholas Gate was extended and then expanded with two rounded bastions flanking the gate building. Both were adapted for the use of artillery and small arms. The gatehouse between them was topped with a battlement, under which the façade was decorated with niches richly decorated with tracery, in the middle of which there were carved figures and cartouches with the coats of arms of the Kingdom of Bohemia and Silesia. In the centre, on a decorative corbel and under a late Gothic canopy, there was a sculpture of the crucified Christ.

Current state

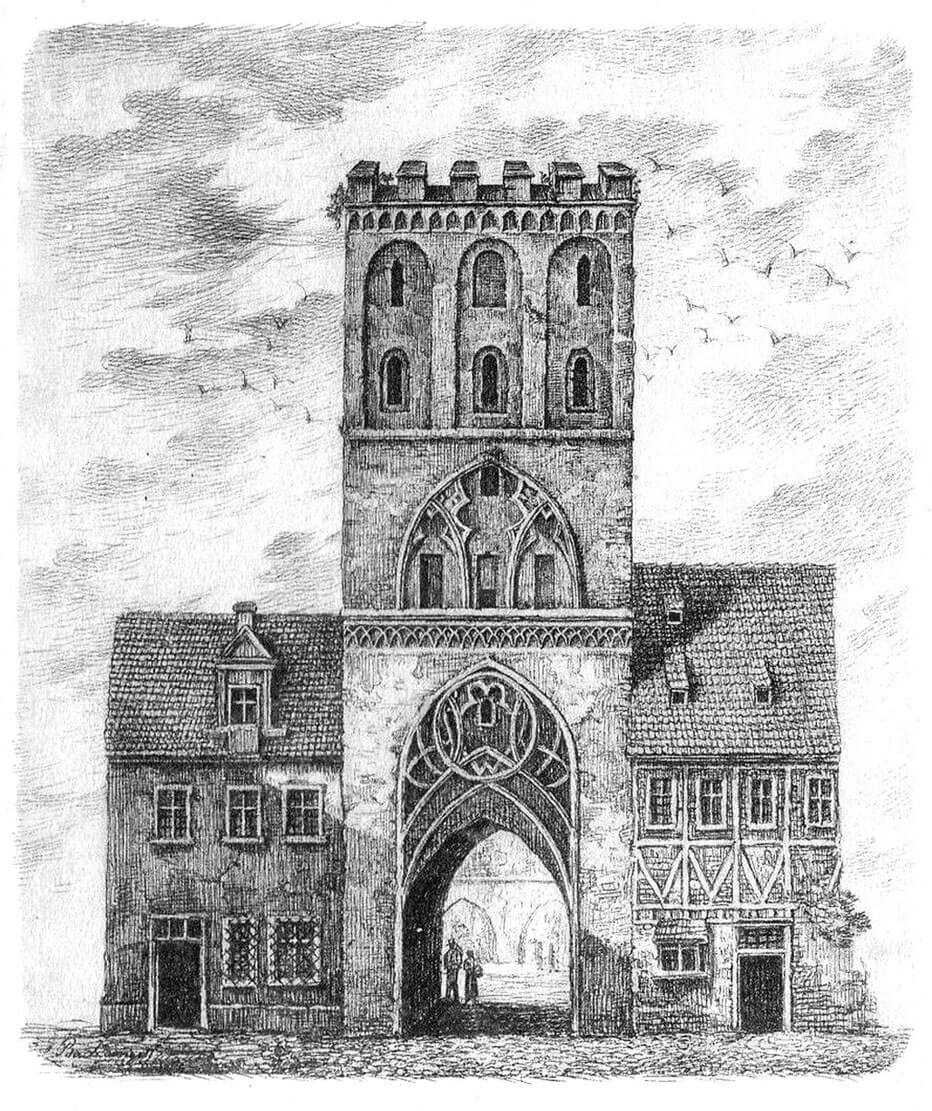

Until today, the extensive fortifications of Wrocław have survived only in a fragmentary state, with paradoxically the most fortunate being the older sections of the walls from the 13th century, incorporated into the residential buildings since the late Middle Ages, discovered and studied since the post-war reconstruction of Wrocław. Of the once impressive city fortifications, the largely reconstructed Bear Tower has survived, along with a short fragment of the wall, located on Kraińskiego Street in the north-eastern part of the former perimeter. On Grodzka Street, a fragment of the reconstructed defensive wall from the 13th century is visible, with a break on the elevation of the building where the half-tower was located. In addition, two towers and curtains of the defensive wall, approximately 78 meters long, can be found on the premises of the city arsenal, currently the seat of the Archaeological Museum (a branch of the Wrocław City Museum). These fragments are the only significant part of the brick fortifications from the 14th century preserved above ground. Under a glass pane, you can see the remains of the lower parts of the semicircular towers and the wall on Wolności Square. The moat called Black Oława and then the city canal from the 13th-century stage of the city’s fortifications, disappeared completely as a result of the construction of the city bypass road in the 1970s. On most of the perimeter, however, the moat created after the 14th-century expansion of the defensive perimeter has survived. Although none of the Wrocław gates have survived, the late Gothic architectural detail of the foregate of the Nicholaus Gate has survived, transferred to the façade of the church at 1 Ołbińska Street.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Atlas historyczny miast polskich. Tom IV Śląsk, red. R.Czaja, M.Młynarska-Kaletynowa, zeszyt 13 Wrocław, Wrocław 2017.

Babral K., Michalski M., Wiatrzyk K., Studium rekonstrukcji bastejowych fortyfikacji Wrocławia na przykładzie reliktów odkrytych w rejonie pl. Wolności, “Architectus”, 3(39), 2014.

Kastek T.A., Obwarowania lewobrzeżnego Wrocławia w XIII-XIV wieku na podstawie badań południowego pasa zewnętrznego obwodu obronnego, Wrocław 2023.

Lasota C., Wiśniewski Z., Badania fortyfikacji miejskich Wrocławia z XIII wieku, “Silesia Antiqua”, 39/1998.

Legut-Pintal M., Mruczek R., The inner perimeter of the town fortifications and its role in townspace: a case study of Wrocław in the transition period from the Middle Ages to modernity, „Archaeologia Historica Polona”, 30/2022.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.

Przyłęcki M., Miejskie fortyfikacje średniowieczne na Dolnym Śląsku. Ochrona, konserwacja i ekspozycja 1850 – 1980, Warszawa 1987.

Przyłęcki M., Mury obronne miast Dolnego Śląska, Wrocław 1970.

Romanow J., Chronologia bramy Piaskowej w świetle wyników badań wykopaliskowych w roku 2000, “Silesia Antiqua”, t. 42/2001.