History

The friary was founded in 1453, on the initiative of John Capistran, a papal legate from Italy, preacher and founder of the Bernardine order, invited to Wrocław by Bishop Peter. Thanks to his fiery sermons, Capistran quickly gained the support of the townspeople against Hussitism, at the same time contributing to the persecution of the Jews. After a short time, he also obtained permission from the city council to establish an Observant (Bernardine) monastery, initially planned for about 16 brothers, but ultimately inhabited by as many as 70-100 monks.

An expression of support for the Bernardines was the donation by the parish priest of St. Maurice plot of land for the planned monastery, on which the first oratory was built in 1453 and consecrated in 1455. Construction of a brick church dedicated to St. Bernard of Siena was started in 1463, initially under the supervision of master Hannos (Hans Berthold) from Lusatia, with whom cooperated the stonemason Peter Franczke and Hans’ son, Erasmus. Construction work in the first stage progressed quickly, as part of the project costs were financed from the city treasury, while the rest of the proceeds came from donations. After a break in 1466 and a change of the construction workshop, the pace of work decreased significantly and it had to be carried out unprofessionally, because in 1491 part of the chancel vaults collapsed. Removal of the damages and further construction continued until the consecration, carried out in 1502 by Bishop Johannes Roth. At the same time, monastery buildings were also built, started from the northern part with a sacristy and a vestibule. Then the western and southern wings were added, and finally, at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the eastern wing and, before 1517, the extension of the southern wing.

The Wrocław seat of the Bernardines quickly became one of the main centers of the Observant movement, primarily due to the provincial chapters held in 1453 and 1454. However, the friary did not function for very long, because with the advent of the Reformation, the Bernardines lost their privileged position, and new ideas turned the townspeople against them. Already in 1522, the city council ordered the Bernardines to move to the friary buildings at the church of St. James, but the brothers, offended by this decision, ostentatiously left the city. The friary was turned into a hospital, and the church, initially closed and unused, since 1526 became an Evangelical parish. Beginning in 1674, there was also a library operating there.

The monastery complex was ravaged by fires many times. Lightning strikes destroyed the church tower in 1557, 1589 and 1609. The most serious fire in 1628 destroyed the walls of the western facade of the church, roofs, vaults and organ choir, as well as, quite seriously, the friary buildings. After the temporary renovation of the roofs and covering them with shingles, the slow reconstruction began, which lasted until the end of the 17th century. In 1634, the chancel vault was restored, and a year later the master bricklayer Georg Sauer strengthened the chancel from the south-east. The windows were also re-glazed. The completion of the work was commemorated with the date 1704, engraved on the new Baroque western gable of the church, but already in 1654 the building was damaged by artillery fire from the Prussian army.

In 1853, a rather unsuccessful reconstruction of the church was conducted. In 1871 the Gothic, eastern range of the friary was dismantled, replacing by the pseudo-Gothic, and in 1872 the friary was dismantled. Another reconstruction of both the church and the friary was conducted between 1898-1901. In this condition, the site survived until the end of World War II. In 1945 the losses were estimated at 60%. The reconstruction was carried out in 1947-1949 and 1957-1967 according to projects and supervised by Edmund Malachowicz.

Architecture

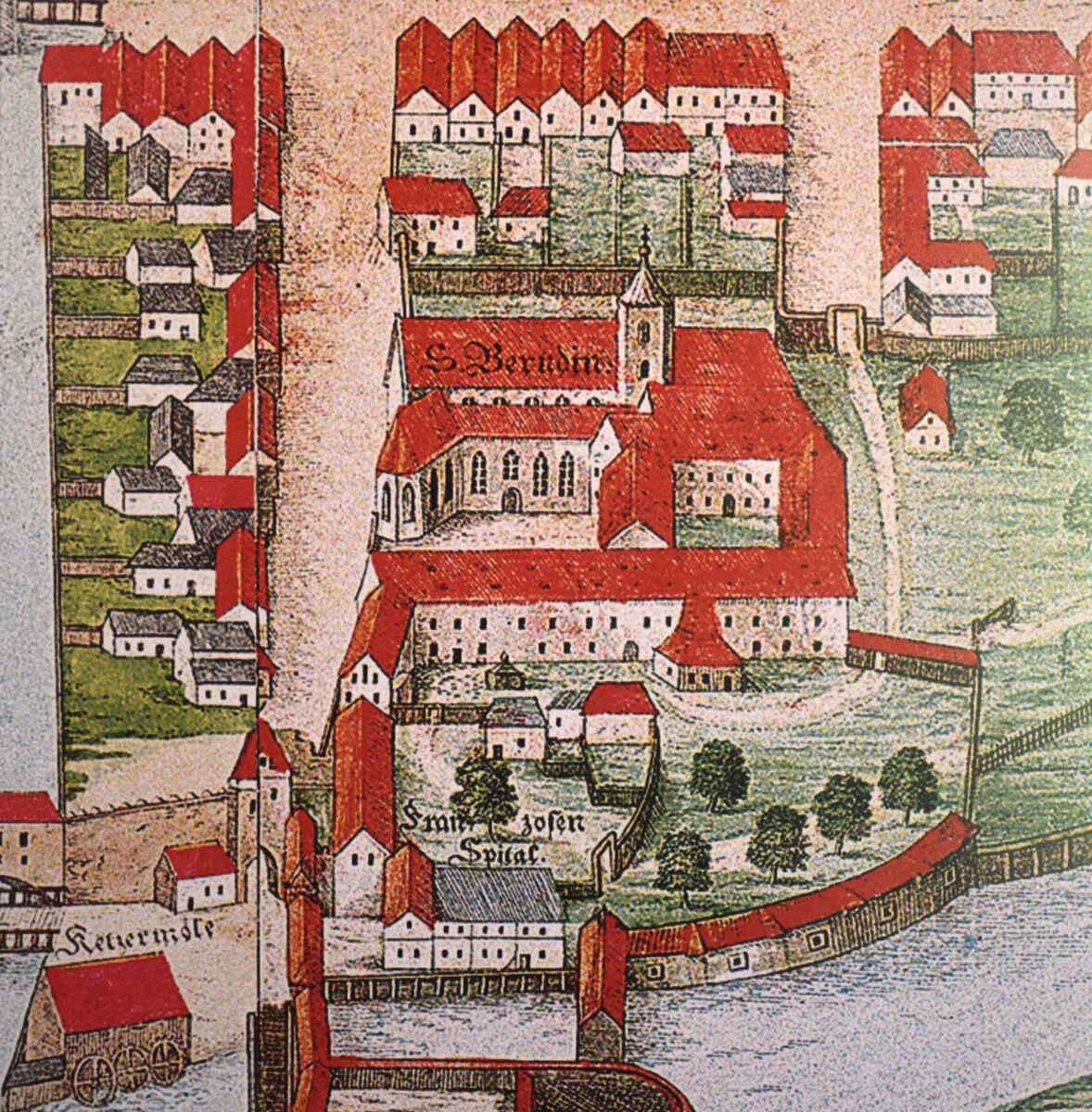

The monastery was founded in the New Town area, which was the eastern part of the urban complex, absorbed by Wrocław in 1327. It was located on the southern side, at the mouth of the Oława River to the moat. The shape of the monastery buildings dominated over the low residential buildings on the western and northern sides and the gardens and orchards on the eastern side. South of the monastery claustrum there were economic buildings with a hospital and mills by the river. There was also a city gate nearby and bridges leading to the Old Town. According to a document from 1453, the Bernardine plot was to cover the area “right next to the city walls, from Hill of Heretics to the Bricks Gate”.

The oldest brick building in the friary was the oratory built in 1453, set on the north-south axis on the south-west side of the later church. It was a single-space, two-story building on a hexagon plan, with a polygonal, non buttressed ending from the south. The upper floor had pointed windows and was topped with a steep, hip roof. Probably the first oratory closed from the west the oldest, longitudinal half-timbered monastery building, located on the east-west axis, partly in the place of the later southern church aisle and adjacent to the southern wall of the half-timbered chancel and the nave of the first church.

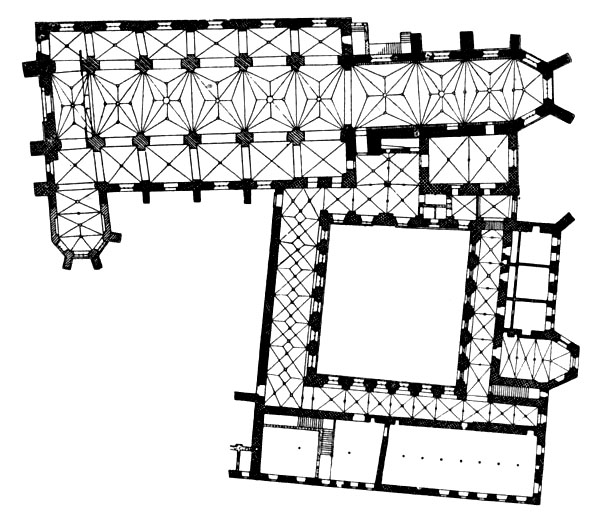

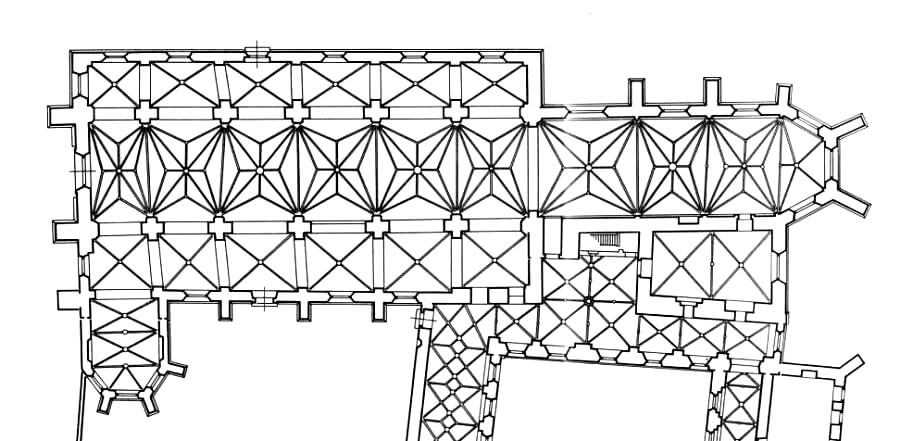

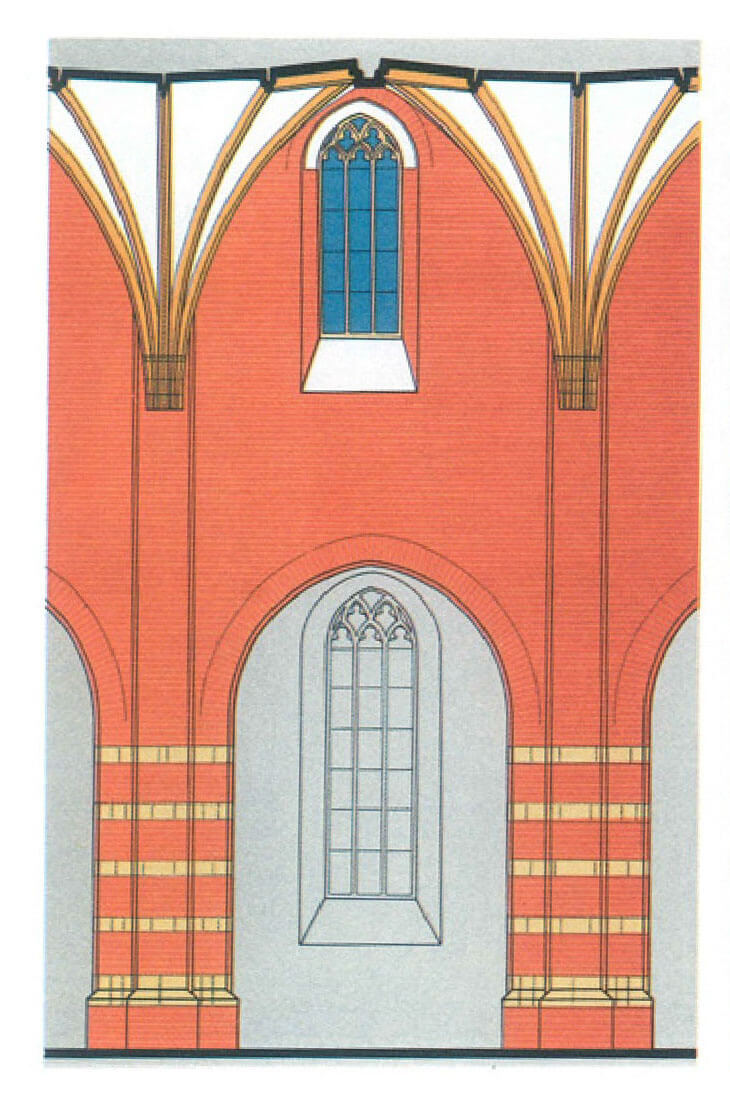

The friary church received a late Gothic form of the six-bay basilica with a central nave, two aisles and an elongated, polygonal ended chancel. It was built of bricks, however, a stone strip every few layers was introduced, a characteristic feature of Hans Berthold’s workshop. The tower, low due to the vicinity of city fortifications, was placed in the corner between the nave and the chancel, on the southern side. The chancel and the southern side of the nave were surrounded by buttresses, and the external facades were covered with plinth, drip and crown cornices. The church was illuminated by pointed-arch windows filled with tracery.

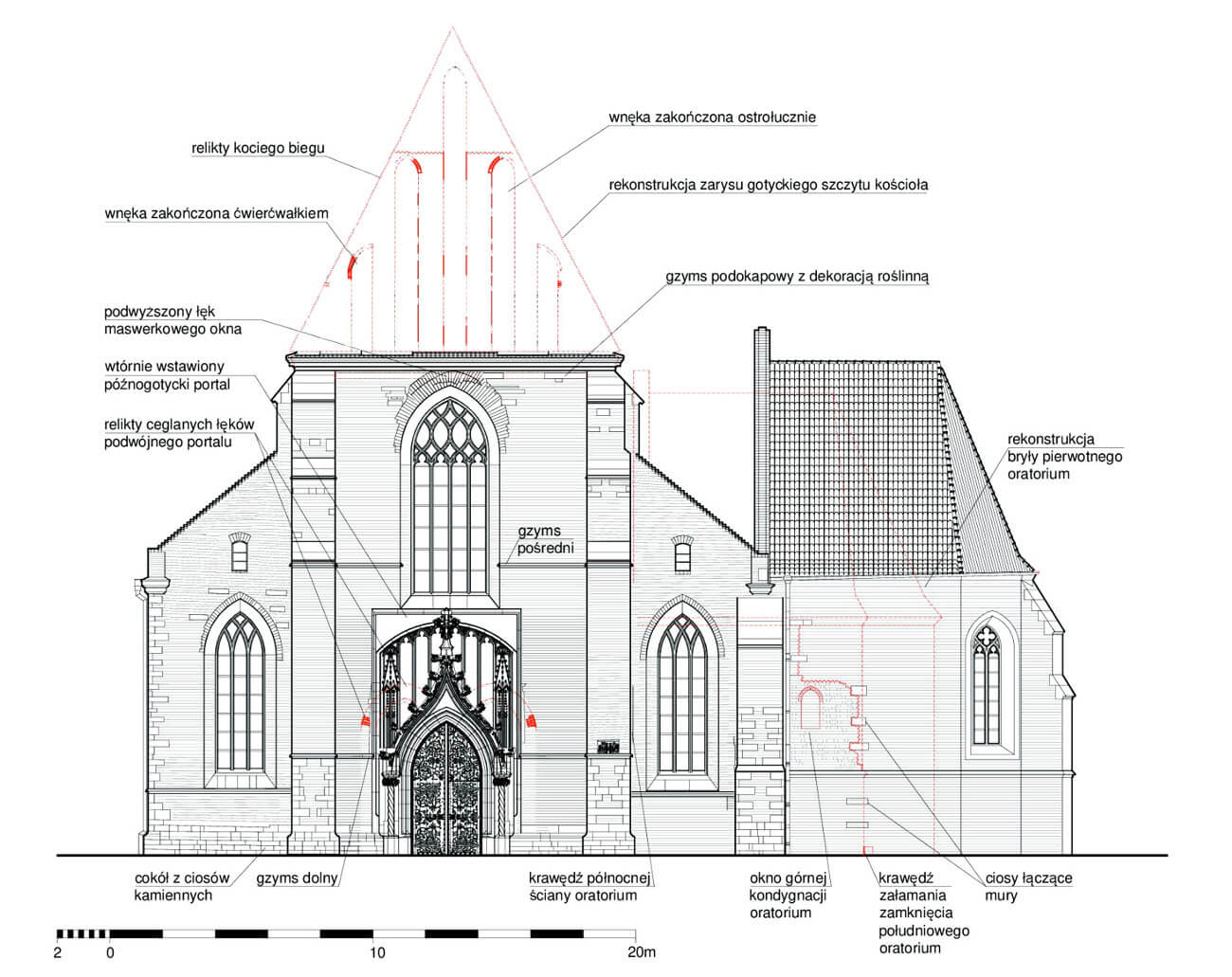

The front elevation of the Gothic church, supported on an ashlar plinth, consisted of a high, topped with a triangular gable facade of the central nave and symmetrically added on both sides lower facades of aisles, covered with mono-pitched gables. The facade was divided by three stone, steep Gothic cornices, with the highest, richest eaves cornice with a quarter round concave, additionally decorated with a sculptural frieze with stylized plant decorations. The central nave was lit from the west by a large tracery, pointed window. The side aisles, without entrances, also had large single, pointed windows. The main, late Gothic, richly decorated entrance portal, topped with an ogee arch, was placed on the axis of the central nave facade (it probably replaced the slightly earlier, double pointed portal). The outer archivolt of the portal was decorated with crockets and topped with a fleuron placed against the background of the blind tracery filling the rectangular frame. The archivolt was flanked by bas-relief pinnacles, inside which were placed further, more slender pinnacles, mounted on two twisted pillars, placed on polygonal, high pedestals and topped with elaborately bas-relief capitals.

In the first quarter of the 16th century, a chapel of St. John was built at the southern wall of the western bay of the nave, created by extending the former oratory. The western façade of the church was initially attached to the north-west corner of the oratory, but in the next stage of the construction of the Gothic church, the southern aisle absorbed its northern part. This required its partial demolition, but the remaining walls were used to build the western wall of the southern aisle and the chapel, moved southwards and roughly retaining the shape and dimensions of the earlier building. Opening of the chapel to the interior of the aisle with an arcade, created structural problems and required additional support of the western wall of the church with a massive buttress. After the expansion, the chapel itself consisted of two rectangular bays and a three-sided closure on the southern side. From the outside, its walls were supported by three buttresses and topped with a gable roof, with the gable part facing the ridge of the church. Inside, the ribs of the cross vault were lowered onto semi-cylindrical wall-shafts, topped with openwork capitals covered with plant ornaments. The vault was decorated with late Gothic polychrome in the form of a flagellum. The above-mentioned arcade was supported on moulded half-pillars, set on stone, five-sided plinths and topped with a moulded cornice.

Inside the church, the irregularly spaced pillars of the cross plan, separate the aisles. The cetral nave and the chancel had stellar vaults, and the aisles cross-rib vaults. The six bays of the central nave were rectangular in shape, while in the southern aisle they were similar to squares and in the northern aisle they were also rectangular (except for the extreme west one) but with the longer sides parallel to the axis of the church. Many of aisles bays had an irregular form, as a result of adapting the walls to older buildings or inadequate planning. Between the aisles there were ogival, moulded arcades, in the aisles lesenes supporting arch bands in the axis of the division into bays. The central nave was connected to the chancel with an arcade moulded with concaves. The chancel was divided into a square western bay, two central rectangular bays and a polygonal eastern closure. Originally, it was separated from the nave by a brick partition – the rood screen. The ribs of its vault were springing from the semi-cylindrical and semi-octagonal shafts with capitals with floral decorations, placed on a prominent offset. In addition, at the arcade, one of the shafts was mounted on a head-shaped corbel. The bosses received the shapes of coats of arms, rosettes, house marks, the head of St. John or the Eye of Providence.

The claustrum buildings were located on the southern side of the church, where, together with the cloisters, surrounded the inner patio. In 1492, there were already three wings. In the northern one there was a vaulted, two-bay sacristy, preceded from the west by a vestibule covered with a cross vault, with brick ribs based on a central pillar. There was a small room between the chancel and the sacristy, leading to the stairs in the tower. On the first floor, above the sacristy, there was a library, accessible from the room above the vestibule. The wide southern wing contained a hall with stairs to the first floor, a large room that could serve as a parlour and a refectory, i.e. the convent’s dining room. The latter was supported on timber pillars dividing the interior into two aisles, covered with a wooden ceiling, and connected to the free-standing kitchen in the south. On the first floor in the southern wing there was a low dormitory, i.e. the monks’ bedroom, but some of the monks’ cells could also be located on the upper floor of the western wing. The eastern wing, built last, housed a chapter house on the ground floor and a chapel extended polygonally to the east.

The most important rooms of the claustrum on the ground floor were connected by cloisters, in the northern part opened to the vestibule. The eastern three bays of the northern passage were separated from the rest of the cloister by a narrow arch band, and their vaults were based on the wall half-pillars between the windows of the cloister and the southern wall of the sacristy. In the three oldest bays of the cloister and in the sacristy room, a similar form of vault and material was used, namely cross-rib vaults with stone ribs. The bays were planned on a rectangular plan, as higher than the other bays of the cloister. The floor was made of small, square tiles covered with glaze. The southern part of the cloister, covered with a cross-rib vault, was finished in the west with a narrow bay, covered with an ogival barrel vault with two ribs, and in the east separated by a wide arch band. The western, widest part of the cloister may have been of wooden construction for a long time, because for this reason one of the windows of the southern aisle was shifted from the axis. At the beginning of the 16th century, it was rebuilt using bricks, divided into irregular bays and covered with a net vault, with ceramic ribs with a biconcave cross-section and bosses in the form of rosettes and circular shields.

In the early years of the 16th century, the southern wing was extended westward. Its interior, covered with a cross-ribb vault, was probably intended to accommodate guests of the monastery. The new part was the only one in friary with a partial basement, so some chambers could also be used to store food and drinks. This wing, the nave of the church and the quadrangle of the monastery were surrounded by a second garden. The Bernardines also had their own bathhouse, a free-standing building on a square plan, built on the plot between the claustrum and the bank of the Oława River. The nearby hospital building of St. Job was placed perpendicular to the southern wing of the claustrum.

Current state

To modern times, the Bernardine friary has survived almost entirely. The exception is the original gable of the church façade replaced with a Baroque one, the pulled down friary kitchen, top of the tower and the eastern wing of the claustrum destroyed in the 19th century and again in 1945, replaced today by a nasty modernist building that brings shame to the city. After World War II, the vaults of the chancel and aisles had to be partially reconstructed, in which most of the original Gothic details were placed. The vaults of the sacristy and the eastern passage of the cloister were also reconstructed. The southern wing along with the western extension were significantly damaged. The church and the friary are now open to the public. Inside is located the Museum of Architecture. Open on Tuesdays 11: 00-17: 00, Wednesdays 10: 00-16: 00, Thursdays 12: 00-19: 00, Friday – Sunday 11: 00-17: 00.

bibliography:

Antkowiak Z., Kościoły Wrocławia, Wrocław 1991.

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. T. Mroczko, M. Arszyński, Warszawa 1995.

Encyklopedia Wrocławia, red. J.Harasimowicz, Wrocław 2006.

Małachowicz M., Pietras K., Przemiany zachodniej elewacji kościoła św. Bernardyna we Wrocławiu [w:] Dziedzictwo architektoniczne. Rekonstrukcje i badania obiektów zabytkowych, red. E.Łużyniecka, Wrocław 2017.

Pierścionek B., Architektura gotyckich klasztorów franciszkanów obserwantów w Polsce XV-XVI wieku, Wrocław 2009.

Pilch J, Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.